|

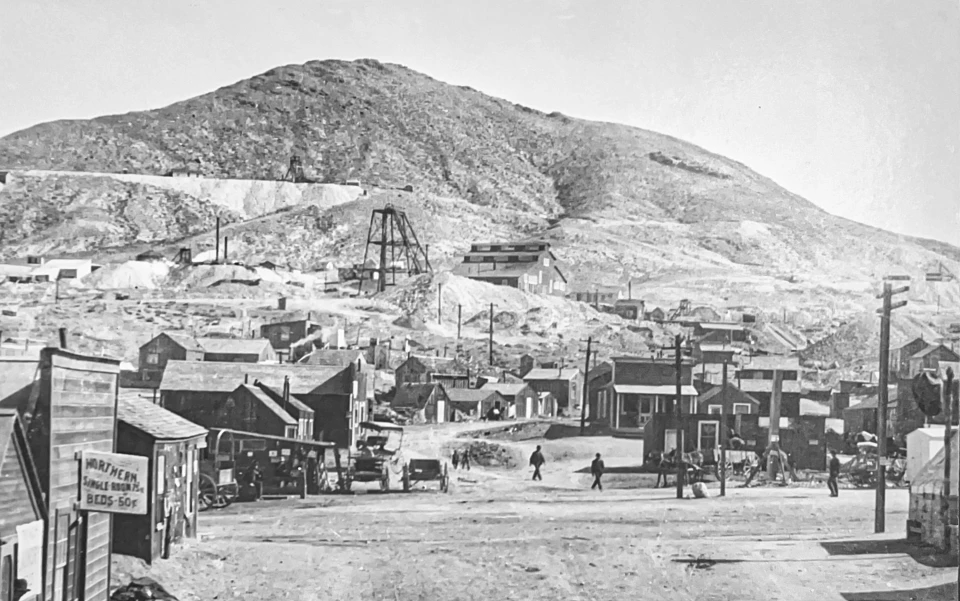

The flow of miners grew around the turn of the 20th Century as word spread of gold that was just lying around on the ground. Nevada boom towns like Tonopah, Goldfield, Rhyolite, and Beatty paved the path southward along what is now U.S. Highway 95. From Rhyolite, old-timers like “Shorty” Harris led new arrivals into Death Valley and its nearby mountains, where they sometimes found deposits of valuable minerals. Millions of dollars of gold, silver, and copper were eventually extracted from some of these mines, but the richest discovery ended up being borax. Tonopah Mizpah Mine - 1904Tonopah, Nevada was the site of one of the richest mining booms in the West. Silver was discovered in 1900 and by 1921, $121 million in silver had been extracted. The town became a major outpost in the Nevada desert, supplying the prospectors that rushed in, including those who travelled to Rhyolite to the south. The Great Depression slowed down production, and then a huge fire in 1942 destroyed much of the remaining mining operations.

Left image

Right image

Greenwater in Snow - 1906The town of Greenwater, located along the Furnace Creek Wash, not far from Dante’s View, was established in early 1906 after the discovery of significant copper-laden ore on the surface. The discovery led to a spectacular short-lived boom. Within a year, Greenwater Valley had over 2,000 inhabitants in four towns, with 73 incorporated mining companies and $140 million in capitalization. Miners flooded in from Rhyolite, Tonopah, and Goldfield. The town quickly transitioned from a tent city to a town with wooden structures; it boasted two stores, a hotel, restaurant, two corrals, and a post office. The Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad mapped out the best route into the area.

Right image

Beatty Main Street - 1906Montillion Beatty, a former Gold Mountain miner and Amargosa Borax worker, took over the old Lander ranch about 20 miles east of Daylight Pass in 1896. He lived there quietly with his Shoshone wife until Shorty Harris and Ed Cross found gold nearby in 1904, giving rise to the Bullfrog Mining District. At that point, Beatty sold the ranch for $10,000, gave his name to the town, and started a new ranch at Cow Creek.

Left image

Right image

Skidoo Baseball Team - 1907Despite its short life as a prosperous town, Skidoo developed a vibrant community. They had two baseball teams - a mine team and a town team. In this photograph, they are posed next to the Skidoo Dance Hall after a game on July 4th. The white uniforms have “23 BBC” which stands for 23 (Skidoo) Base Ball Club. Behind the baseball team, a group of men move a piano over to the dance hall.

Left image

Right image

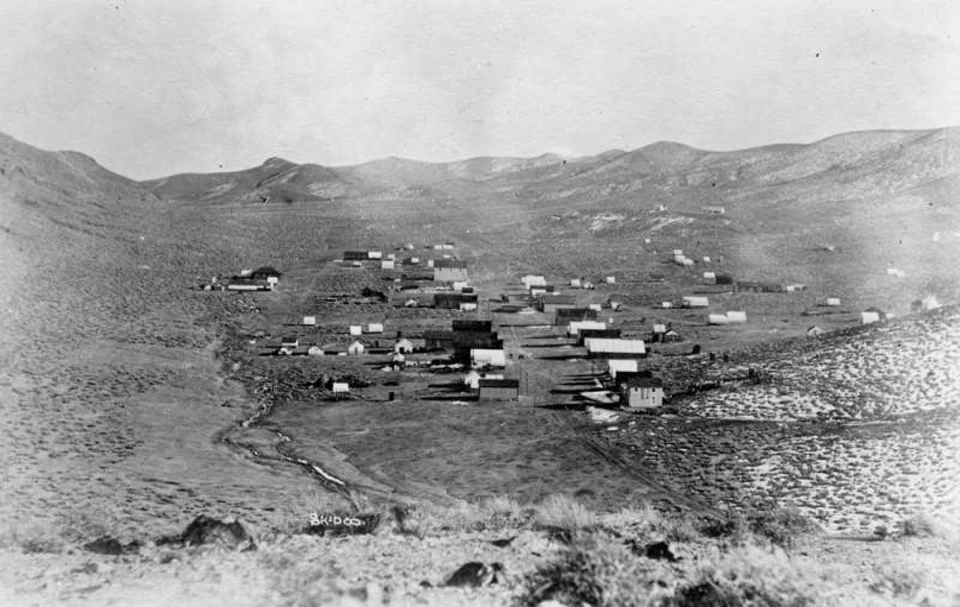

Skidoo from Above - 1908The town of Skidoo was located in the Panamint Mountains, northeast of Emigrant Canyon. In its heyday, the gold mining town had a population of 500, a newspaper, a bank, a school, a brothel, telephone service, and at least one saloon. However, it was prosperous for less than two years.

Left image

Right image

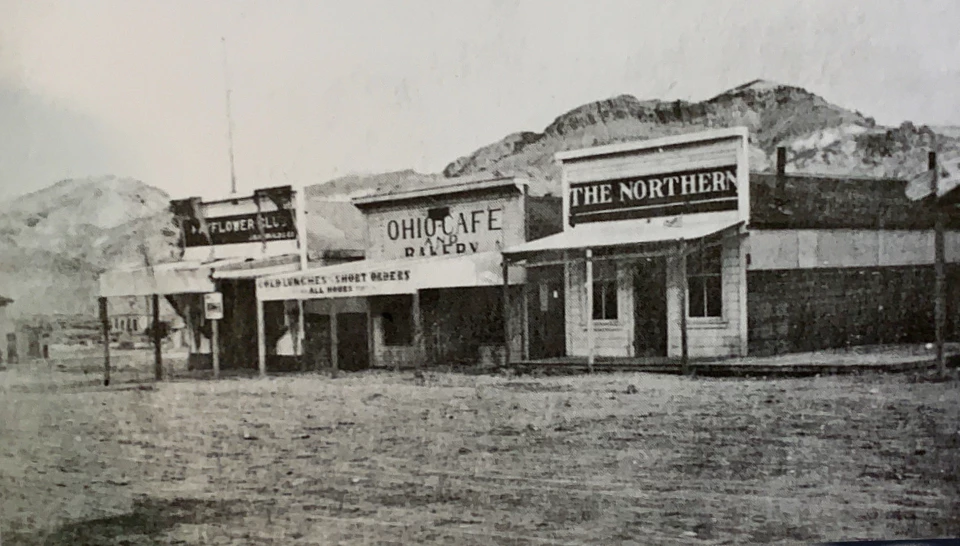

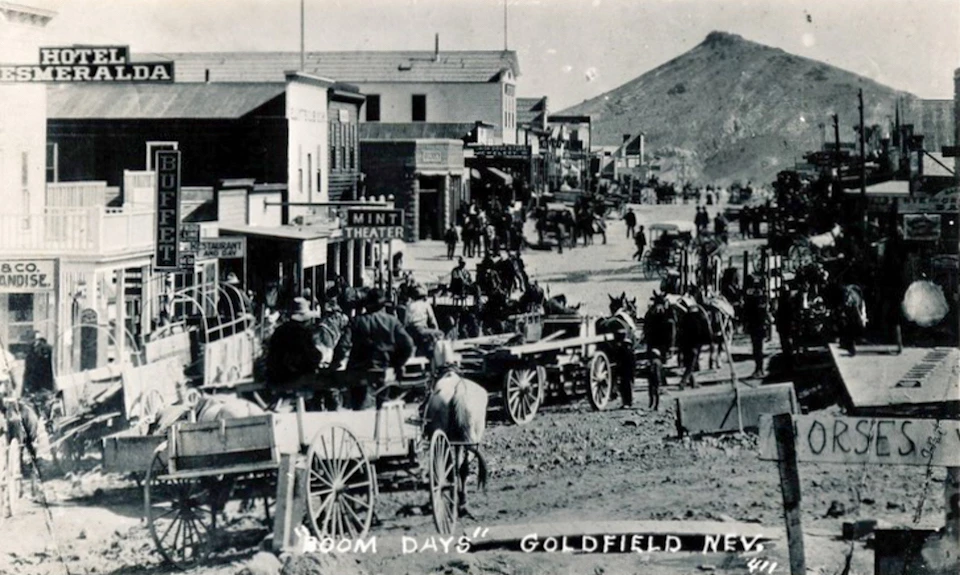

Goldfield Boom Days - ca. 1908From 1906 to 1910, Goldfield was the largest city in Nevada. Located south of Tonopah, it became the leading political and economic power in the state with a population of over 20,000. Virgil Earp was the sheriff, and his brother Wyatt lived there for a time.

Left image

Right image

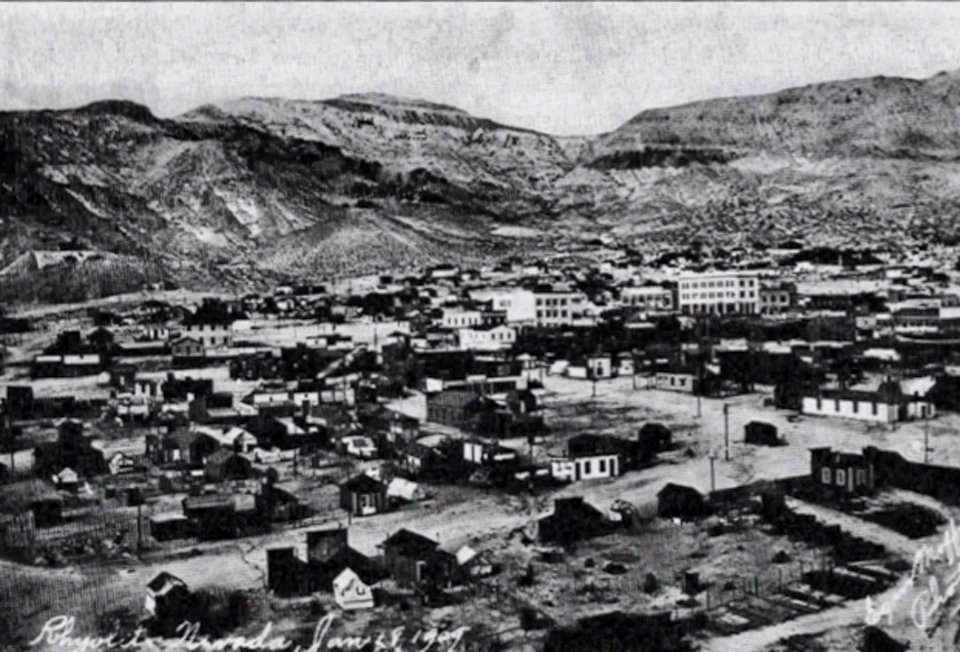

Rhyolite from Above - 1909After Shorty Harris’s discovery of gold at Bullfrog in 1904, the town of Rhyolite sprang up and grew to 10,000 citizens within two years. People thought the Bullfrog and neighboring mining districts would last a long time, so they built tall and sturdy buildings of stone and masonry. The Montgomery-Shoshone Mine, one of the largest in the district, was purchased by Charles Schwab in 1906 for between 2-6 million dollars.

Left image

Right image

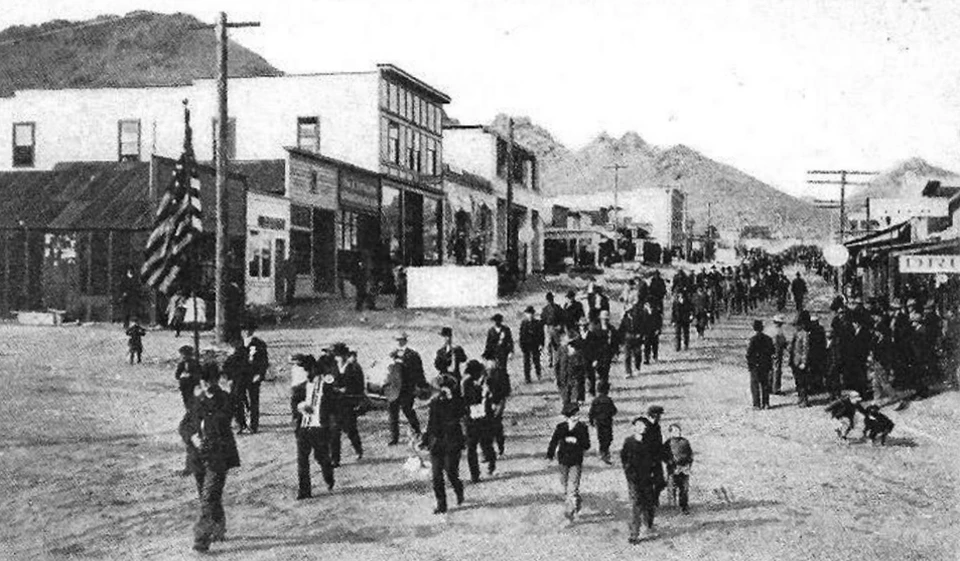

Rhyolite Miners Union Parade - 1909The financial panic of 1907 took its toll on Rhyolite and was seen as the beginning of the end for the town. In the next few years, mines started closing and banks failed. Newspapers went out of business, and by 1910 the production at the mill had slowed to $246,661 and only 611 residents remained in town. On March 14, 1911 the directors voted to close down the Montgomery Shoshone mine and mill. In 1916 Rhyolite’s light and power were finally turned off.

Left image

Right image

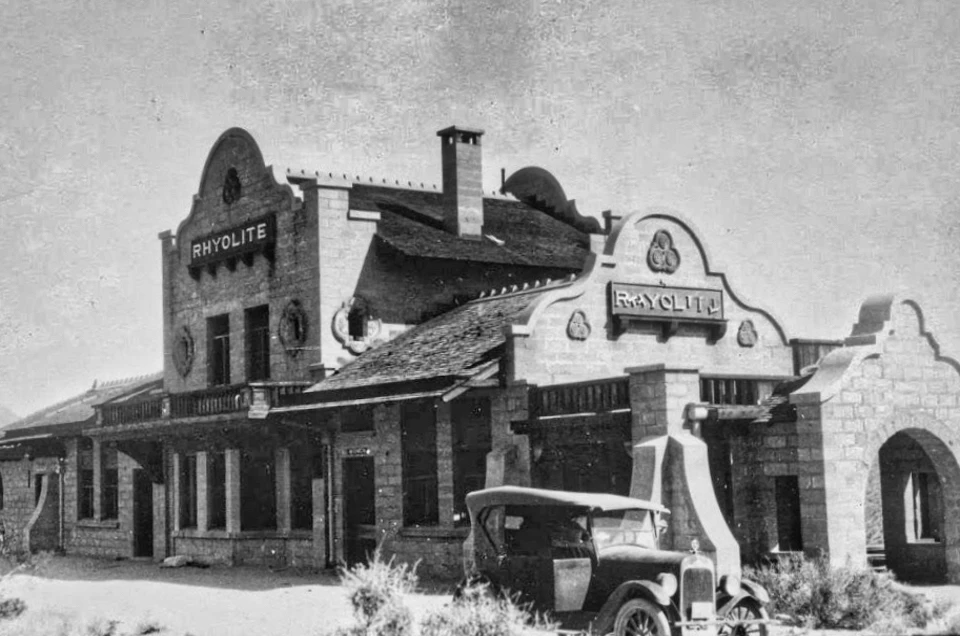

Rhyolite Train Depot - 1920Rhyolite’s rapid growth as a mining center brought three railroads to service the town and surrounding mining district. The Las Vegas & Tonopah sent its first train into Rhyolite on December 14, 1906 with 100 passengers. By 1907, The Las Vegas & Tonopah railroad was hauling 50 freight cars a day into town, which necessitated the building of a large depot.

Left image

Right image

Darwin Saloon - ca. 1910In 1874, Darwin was one of three areas west of Death Valley (Darwin, Panamint, and Lookout), where significant deposits of silver were discovered. The town was founded by the prospector Dr. Eramus Darwin French, who also named Furnace Creek when he found a small, air-blast smelting furnace in that creek.

Right image

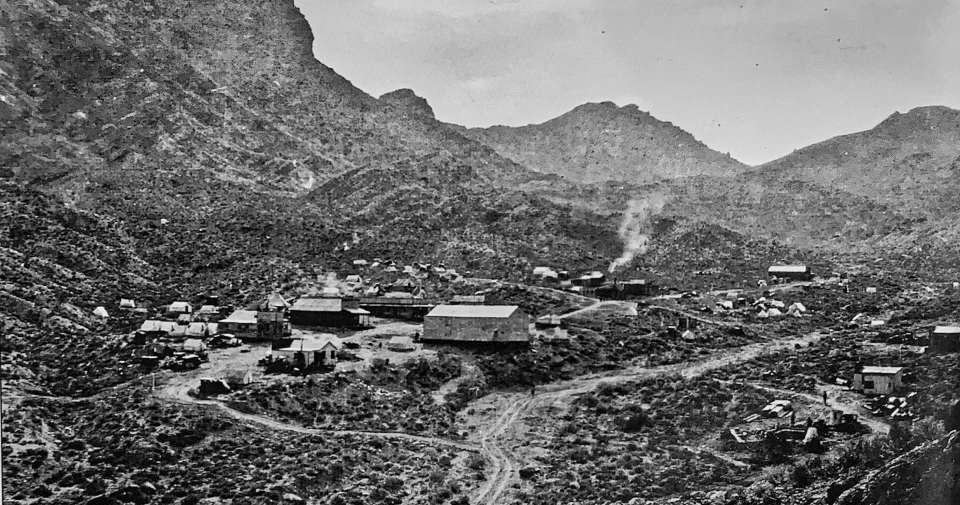

Leadfield from Above - ca. 1925Lead and copper were first discovered in Leadfield in Titus Canyon in 1905 but after some effort, mining companies decided that the cost to ship ore across the mountains to Rhyolite made operations unprofitable.

Left image

Right image

Amargosa Hotel and Pacific Coast Borax Co. - ca. 1925The Pacific Coast Borax Company was established in late 1890 by Francis Marion Smith (also known as the Borax King). Smith bought all of the assets of William Coleman, the San Francisco mining entrepreneur who had established the Harmony Borax Works near Furnace Creek. Smith hired a young Stephen T. Mather to head the company’s advertising and promotion efforts. Mather later became the National Park Service’s first director and played and key role in the establishment of Death Valley National Monument. Mather was largely responsible for the “Twenty-Mule-Team Borax” product name.

Left image

Right image

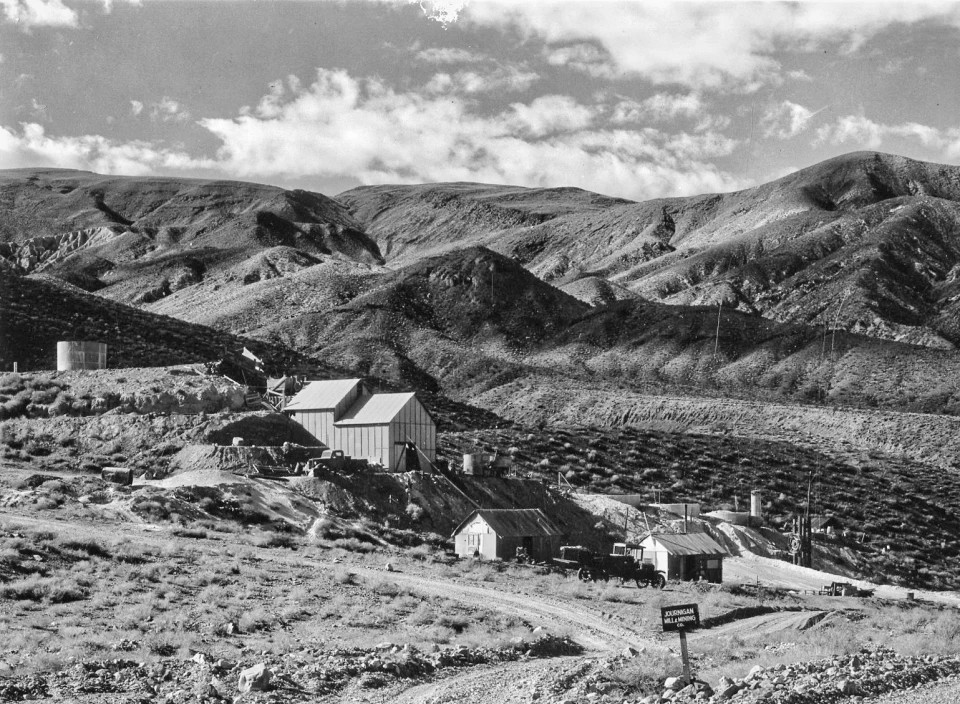

Journigans Mine and Milling Company - ca. 1940Several mining towns were located in and around Emigrant Canyon, including Skidoo and Harrisburg. Transporting ore to distant smelters was an expensive and arduous endeavor. In 1934, Roy Journigan bought this mill site and water rights to four local streams in lower Emigrant Canyon. He built the mill which increased mine owners’ profits by reducing the distance they needed to transport the heavy raw ore.

Left image

Right image

|

Last updated: August 9, 2022