|

Death Valley is no stranger to the challenges that have confronted American society over the past 150 years: the Timbisha fought to hold on to their homeland, Depression-era workers struggled for an economic foothold through the Civilian Conservation Corps and Japanese Americans were rushed to Cow Creek from their incarceration at Manzanar during World War II. Timbisha Huts at Furnace Creek - 1928The Death Valley Shoshone have populated the desert for centuries. Some archeological objects found southwest of the park may be from the Lake Mojave period (10,000 to 5,000 BCE). During that period, there were more plants and large fauna than there are now. As the climate warmed, indigenous people wintered on the floor of Death Valley, and moved to the cooler climes of the mountains during the summer months. They took the name “Timbisha Shoshone” when they received federal recognition in the 1980s.

Left image

Right image

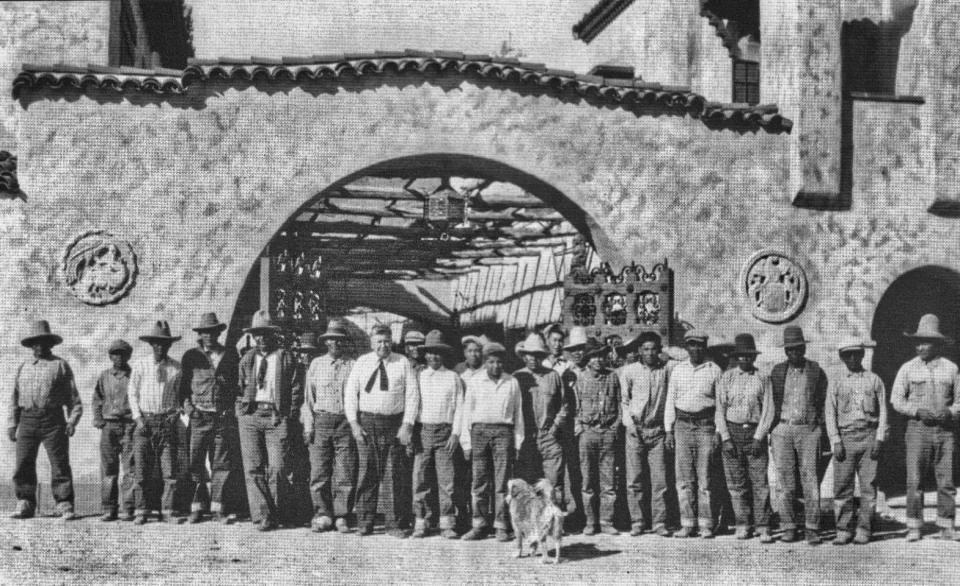

Shoshone Workers at Scotty's Castle - ca. 1930As the borax mines started closing, a group of Panamint Shoshone who were living and working in Death Valley started to work for Albert Johnson to help build Scotty's Castle. As Euro-American society encroached on the traditional lands and livelihoods of the indigenous people of Death Valley, they were forced to work for white men in order to make ends meet. Construction of Scotty’s Castle was one such opportunity. A hatless Death Valley Scotty is in the white shirt and tie, posing with some of these workers.

Left image

Right image

Camp Cow Creek - ca. 1935Shortly after Death Valley was established as a national monument in February 1933, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) sent two companies of men (400) into the park They were housed in three camps – Wildrose, Funeral Range, and Cow Creek and were paid $25 per month, of which $20 went to their family and $5 to the men.

Left image

Right image

Baseball at Manzanar - 1943President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, authorizing the military to remove “any or all persons” of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. Over 11,000 of the 120,000 people affected by this order were incarcerated at Manzanar, just west of Death Valley and south of Independence in the Owens Valley of California.

Left image

Right image

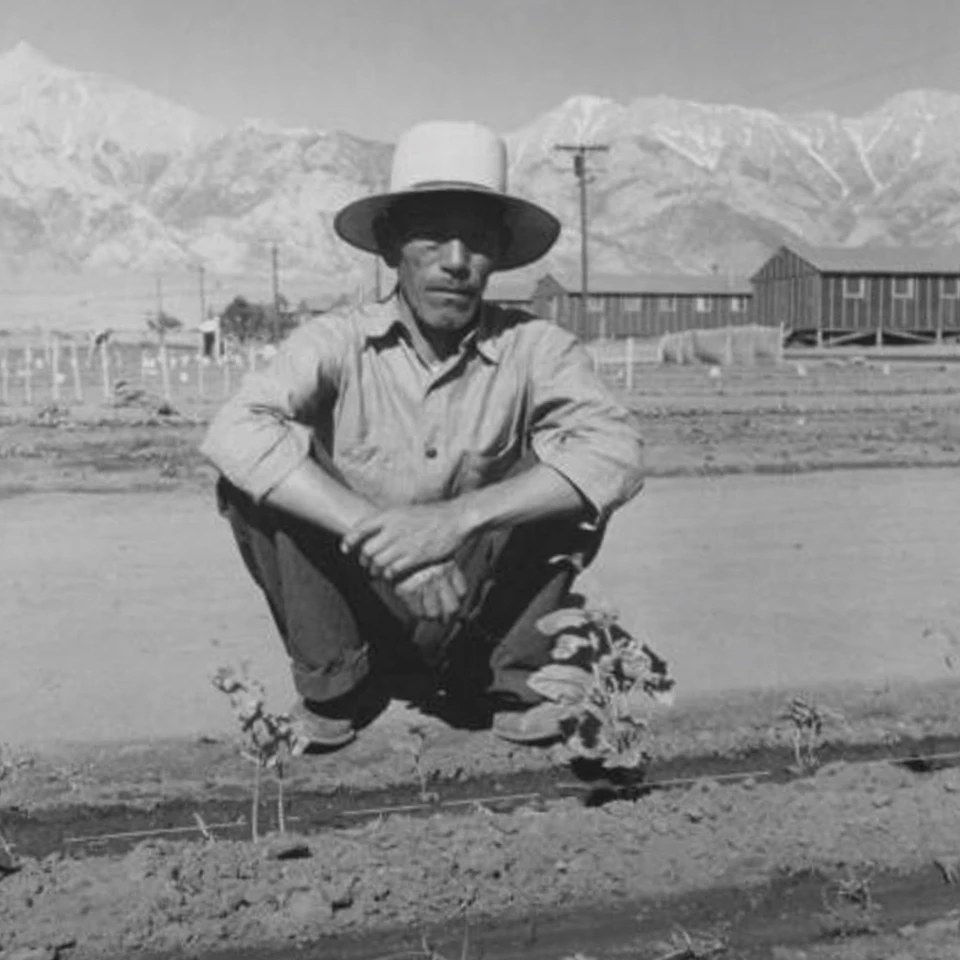

Manzanar Nurseryman - 1943Gardens and parks built by those incarcerated at Manzanar served as a respite from the reality of being torn from their pre-war lives and being imprisoned by their own country. The circumstances created by the government contributed to the rising tensions that erupted in the revolt of December 1942.

Left image

Right image

Cow Creek Camp - 1942Between December 1942 and February 1943, 65 Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated at Manzanar in the Owens Valley were removed to the old Civilian Conservation Corps facilities at Cow Creek. These families were removed to Death Valley after a series of protests ended with Military Police firing on a group of incarcerated people at Manzanar. While at Death Valley they worked in the then monument and helped to improve infrastructure. They were eventually placed in jobs outside the West Coast.

Left image

Right image

Timbisha Demonstration for Homeland Restoration - 1996For generations, the native people of Death Valley and the Eastern Sierra fought for legal status as a tribal organization. They were pushed to the edge of existence first by the growth of mining interests and then by the National Park Service’s approach to “wilderness,” from which the government removed all people.

Left image

Right image

|

Last updated: January 30, 2025