Interview

An Interview with Hester Davis

by Barbara J. Little

|

Courtesy of Hester Davis |

Hester A. Davis has served as a board member or officer of the Society for American Archaeology, Register of Professional Archaeologists, Archaeological Institute of America, Southeastern Archeological Conference, Southeastern Museums Conference, and U.S. National Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites. In the 1980s she served as Coordinator of the Coordinating Council of National Archeological Societies. She served on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Chief's Environmental Advisory Board from 1988 to 1991. She was appointed by President Clinton to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee on which she served for seven years. From 1969-2000 she was a member of the Arkansas State Review Board on Historic Preservation (appointed by Governors Rockefeller, Bumpers, Pryor, Clinton, White, Clinton, and Tucker).

In 1959 she accepted a position with the University of Arkansas Museum, where she served first as Preparator and then as Assistant Director. In 1967, with the creation of the Arkansas Archeological Survey, she was appointed State Archeologist, a position in which she served until her retirement in 1999. She also taught in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Arkansas, among other things creating and teaching a course in Public Archaeology for 10 years. She retired as a full professor. She holds two Masters of Arts degrees, one in Social and Technical Assistance from Haverford College in Pennsylvania and one in Anthropology from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. She earned a Bachelor of Arts in History from Rollins College (Florida), which also awarded her a Doctor of Humane Letters in 1987. Lyon College (in Arkansas) also awarded her a Doctor of Humane Letters, upon her retirement.

Barbara J. Little (BJL), CRM Journal Editor, interviewed Davis on April 24, 2009.

BJL: Tell us how you became interested in being an archeologist. What experiences and individuals influenced your career choice?

HAD: I don't remember thinking about and making a decision about a career. I followed some opportunities as they drifted by.

The first really influencing contact with archeology was in the spring of 1950 when I was a sophomore at Rollins and looking for something interesting to do for the summer. My sister Penny, who was a graphic artist at Peabody Museum at Harvard, suggested that I write to Jo Brew [John Otis Brew] the director at Peabody and see if there might be a field crew going to the southwest that could use a hand. I did that, and there was. I received back a letter from Charles R.[Bob] McGimsey III, a grad student at Harvard, who was heading a field crew to test several sites in west-central New Mexico. This was not a field school, nor was it a paying job. Food and lodging (a tent camp) were free. If I could get myself out to Albuquerque, someone would pick me up and bring me to the camp. I could and they did, and I spent a great summer (a crew of about 10) learning about archeology. The next summer I did the same thing. Peabody had a small crew that year of field school students testing some more sites near those dug in 1950. I was in charge of the lab that summer, and Jo Brew and Watson Smith were the supervisors of the crew.

BJL: Is that when you began to consider archeology as a career?

HAD: It was there that I had evening discussions about my future with both Jo and Wat. Jo advised me to learn a skill like Penny had in drafting, because there were not many jobs for females in field archeology. Wat, however, said that Dr. Luther Cressman at the University of Oregon took females on his field school, and if I wanted to go into archeology that was probably the most promising place. So I applied to the grad school at the University of Oregon for the fall of 1952. I graduated from Rollins with a degree in History (they taught no anthropology at the time), and having been accepted at UO, I was looking for a job for the summer of '52. By this time my archeologist brother Mott was teaching anthropology at the University of Nebraska. Lincoln was at that time the headquarters of the work sponsored by Smithsonian and the National Park Service of sites to be inundated by many reservoirs in the Missouri River Basin. So I asked Mott to see if there was a crew that might need me.

As it turned out, Robert Stephenson was director of that RBS [River Basin Survey] work that year and he didn't like to have women on his crews. However, some of those looking to put together a crew for their work didn't have the same feelings and I was hired by Dick Wheeler to be part of his crew; actually there were two of us females. As I recall, the other girl was coming from the New York City area, but she had to drop out a day or two before the beginning of the project. So off I went to Jamestown, North Dakota with a small crew. I lived with the family who owned one of the sites we were to dig, and the males lived in an abandoned schoolhouse nearby. After the first couple of weeks, Dick found that the woman who was feeding us was also feeding her family of five and charging Dick for that. So he asked if I would be cook. Sure, says I, why not. I cooked on two two-burner Coleman stoves and took pictures at the site for the rest of the summer.

BJL: You didn't go right back to archeology, did you?

HAD: I hopped a Greyhound bus (which I have never ridden since!) and went to Eugene, Oregon, for the next phase of my journey through life!

I stayed in Eugene for two years, learning anthropology. I was captivated by the idea of using anthropology to make the world safe for democracy, and decided that was what I wanted to do. Providentially, I learned of a one-year graduate program at Haverford College in Pennsylvania that was sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee. They were teaching students who wanted to go overseas to what were called at the time "undeveloped counties," to help them recover from the ravages of war. I applied and was accepted. There were nine of us in the program that school year, and I was the only one who already had some background in anthropology. We spent Christmas break on the Cherokee Reservation in North Carolina, with Dr. Gordon McGregor as our teacher for those six weeks, learning about another culture.

BJL: So you decided to be a cultural anthropologist?

HAD: I decided I better get my MA in Anthropology. So I finished the MA thesis at Haverford, applied to grad school at Chapel Hill, and was accepted. The summer of 1955, before going to Chapel Hill, I spent six weeks on Mott's University of Nebraska Field school, again as cook and photographer and sole female on the crew (with Mott to look after me, of course). By the beginning of 1957 I had my anthropology MA in hand and was again in need of a job. The Institute for Agricultural Medicine at the University of Iowa's Medical School was looking for a research assistant to do field work on a project recently funded by the Kellogg Foundation. I was hired. I drove from Chapel Hill to Iowa City in March of 1957. I was to do participant observation for 13 months in a farm community and in the family, which included a boy of 5.

I visited Iowa City to make progress reports about once a month, and would visit in Rey Ruppé's Archeology Lab. Soon the grad student cohorts became good friends and several times I went on weekend digs with them. Ruppé ran a field school every summer, and I managed to arrange to be hired as cook for that six week period in the summer of 1958! I had finished the 13 months on the farm in June, and the field school started in July. It was great fun. I then returned to Iowa City, and spent the rest of 1958 and the first six months of 1959 there working on my final report entitled "Open County Culture." I think I gave my first paper at the AAA [American Anthropological Association] annual meeting.

BJL: But cultural anthropology had less appeal ultimately than archeology? Why was that?

HAD: My problem was that I didn't like asking personal questions of people, even when I was no longer a stranger. During the early spring of 1957 I began writing letters to all the archeologists I had met along the way, asking about a job.

Bingo! In 1957 Bob McGimsey had been hired at the University of Arkansas to teach part-time in the department of Sociology and Anthropology and be part-time "curator" of the University Museum. For the 1958-1959 Legislative Session, he had been asked to present a budget and proposal for the university to create a Laboratory of Archeology on the campus in Fayetteville. This he did and Governor Faubus signed the bill creating the laboratory, but vetoed the bill for $35,000 funding. McGimsey then went to the Dean and said "What if we turn the half-time secretary position into a full-time research assistant for the Museum using other money that you might have" (or something to that effect). Anyway, the Dean must have felt sorry for him, because he agreed. I was offered the job and grabbed it, arriving in Fayetteville on July 1, 1959, which turns out to be 50 years ago!

BJL: How did you become the first State Archeologist?

The position of State Archeologist was created as part of the Arkansas Archeological Survey, which came into being on July 1, 1967. There was no job description, so McGimsey and I made it up as time went by. Because he was traveling a lot, the basic job was administering the Survey's research stations around the state and running the Coordinating Office. For about ten years from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s I also served as archeologist for the SHPO office for reviewing and commenting on projects. The Arkansas Archeological Society was created in 1960 as a means of making contact with amateurs. Either McGimsey or I published a monthly newsletter and an annual publication, The Arkansas Archeologist. In 1965 I became sole newsletter editor, a position I held through February 2008.

And that's how I took opportunities as they came along, and I ended up with a career, which might be called archeological administrator.

BJL: In addition to following opportunities, what influenced you most?

HAD: I worked for the University Museum for 8 years and as State Archeologist for 32 years. The experience that most influenced me, I think, was the observation that field archeologists always seemed to have a lot of fun. The opportunity I had while on the Cultural Property Advisory Committee was the most interesting, as it introduced me to many people working outside the U.S. and to the many international problems other countries had because of looting and smuggling.

The persons who most influenced me as far as archeology goes are brother Mott, Wat Smith (giving me good advice), all those field archeologists having so much fun, and Bob McGimsey.

BJL: You played an important role in the "Summer of 1974," which was a milestone for public archeology in the United States. Could you tell us what was so important about that time and what enduring lessons archeologists today might draw from it?

HAD: Ah, yes the "Summer of '74." I'll start with the high point, which was May 24 when Present Nixon signed what was known to all archeologists at the time as the Moss-Bennett bill, which became, officially, the Archeological and Historic Preservation Act. We, the whole profession, actually, had been working for its passage since it was introduced in 1968. I was Chair of the [Society for American Archaeology] SAA Committee on Pubic Archeology at the time (the committee consisted of one person from each state), and during those six years I periodically sent notices about progress in getting the bill through Congress, and advising archeologists of what and how they could help see that the bill would eventually become law. I think this experience politicized the profession as no previous legislation had, not even the National Historical Preservation Act, which had essentially no archeological input at all.

The importance of the act was, of course, that it put archeology squarely in the preservation process developing at the time as regulations were being developed by the National Park Service [NPS] and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Importantly, it also provided that all federal agencies that needed archeological work to be in compliance with federal law could now spend their own money for such purposes. Previously they had to depend upon getting funds from the National Park Service, the only agency with authority and specifically appropriated funds for archeology (which were never adequate). Of course it took several years of the budget cycle for agencies to request this money from Congress and to get personnel to oversee their own archeological programs. It is my opinion that this was the beginning of CRM [cultural resource management] as we know it.

BJL: What else was happening during that time?

HAD: The other major happening that summer (not to mention activity before and after May 24), that had been at least six months in the planning were the Airlie House Seminars. In May of 1974, Bob McGimsey (my boss at the Arkansas Archeological Survey) had been elected President of SAA. He had been working for the passage of the Moss-Bennett Act since 1968 and in the spring of 1974 felt strongly that the profession needed to be ready for what was going to happen when that bill did pass. He picked six themes that he felt needed discussion, and suggested they be considered in six weeklong seminars. Those became the Airlie House Seminars named for the conference center west of Washington, DC. The funding came from the park service. The themes covered the law, CRM, guidelines for reports, the crisis in communication, relationships between archeology and Native Americans, and certification and accreditation.

BJL: You and Bob wrote the conference report, which is still frequently cited. Why do you think it was so influential?

[McGimsey III, Charles R. and Hester A. Davis, The Management of Archeological Resources. The Airlie House Report (Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology, 1977)].

HAD: In terms of your question, the six topics of the seminars were important for archeologists to think about and make suggestions to the profession as to ways the topics might best be handled when the "new" money was available, and when many more archeologists found jobs having to do things for which most were not trained, such as preparing estimates for time and money on projects with very specific boundaries.

Let me add one more thought. What enduring lessons archeologists might draw from this special summer? Be Prepared!

BJL: In your view, how has public archeology changed over the course of your career?

HAD: I think the first use of the term that I recall was by the SAA in the creation of a Committee for Public Understanding of Archaeology. That pretty quickly changed to Committee on Public Archaeology, which had a much better abbreviation—CPUA wouldn't do, COPA was better. I was chair of COPA for a while in the late 60s and early 70s, spreading the word to archeologists about the Moss-Bennett Act.

One thing I know that has changed drastically is that public archeology now means many things to different people, and that the term and its practice has spread worldwide.

BJL: I see that you've brought one of the first important books on public archeology.

HAD: Yes, and this is the first time that I know of that the concept was published, in Bob McGimsey's Public Archeology in 1972. In that he was passing on the information he had gathered from around the country on archeological programs supported with state funds, that is, public money. It was a sorry showing, given the rate of destruction of sites by postwar construction, farming, road building, and so on. We've heard this lament for at least 35 years. For example, if I may read from Bob's book (page 3). "The United States Soil Conservation Service confidently expresses the opinion that within 25 years [that was 38 years ago], all levelable land in Arkansas will have been leveled [in the Mississippi Valley and that of the Red River in the southwest corner of the state]. That constitutes over one-third of the total land surface in the state and includes a major portion of the heartland of the Mississippi and Caddo archeological culture areas."

He says he wrote the book with two audiences in mind: his colleagues, who might take the case of the creation and funding of the Arkansas Archeological Survey in 1967 to their legislators and convince them to fund a similar program to save their state's heritage. The second audience was the legislators themselves, "and other interested citizens" (page xiii). He is essentially challenging everyone with any interest in the past to become leaders in preservation of that past. "Public participation provides the potential for archeology's salvation" (page 37). In challenging his colleagues to see that "the public" is involved in this effort, he says, "Public participation can produce the four key elements that must be called into play if there is to be any hope of preserving any meaningful portion of this nation's past before it is destroyed. These four elements are: 1) adequate financial support for professional efforts), 2) an effective medium for increasing understanding of archeology on the part of that portion of the public which controls the land, 3) local resources [amateurs] that can be called upon readily in cases of emergency, and 4) experienced auxiliary forces [amateurs] that can carry an increasingly significant part of the investigative load." He then goes on to lecture professional archeologists not to be condescending in their relationships with amateurs. Remember, they are volunteers.

BJL: You said earlier that the term "public archeology" has changed drastically. Have other publications become as influential as McGimsey's book?

HAD: In some ways the book is out of date. Much of what Bob was saying has been repeated in many forms over the years. It would be interesting to find some grant money and make a survey of state programs now to see what "progress" in what areas has or has not been made.

In terms of worldwide use of the term in theory and in practice, I have recently come across a book published in 2004 by Routledge, edited by Nick Merriman of the Institute of Archaeology at University College in London. The book has the same title as McGimsey's book (although archeology is spelled archaeology). There are contributions spread geographically (all over the world) and topically, from programs involving the public in museums, to the Treasure Act in England and the relationship of metal detectorists and archeologists; from public education to using technology and media.

BJL: How has the professional community changed the way we think about public archeology?

HAD: The SAA's Committee on Public Archaeology has morphed into the Public Education Committee, and has had a strong program of developing literature for teachers, particularly in the primary grades. Most states now have an Archeology Week or Month to concentrate information on archeology going out to many audiences; demonstrations (flint knapping, atlatl throwing, etc), talks, posters, interviews, special exhibits, and short term excavations for people to visit and/or volunteer to learn about archeology. There are now a good many states with various versions of the Arkansas training program for amateurs. It is certainly my impression that there is a lot of this kind of activity going on in this country and others, more than it would be possible to inventory. In the early 1960s when I was active in the SAA Committee there was little of this going on.

Another interesting change is that soon after archeologists became aroused to the fact that talking to the public was part of their job, historians realized the potential for jobs outside of academia with State Historic Preservation Programs and with large companies needing professional historians to aid in recording historic sites in their project areas. Public history as a sub-subject has separate departments in universities now, and has a very active national organization (National Council on Public History), which produces a newsletter and a quarterly journal.

The feds have made an effort to see that where public (federal) money is being used for archeological research, that information from such projects be made available to the local community in the form of public lectures, newspaper articles, storefront exhibits, and/or the publication of non-technical publications about the project. Even Congress has gotten into the act (pun intended) by mentioning in new or amended legislation that the public needs to be informed of what a federally funded archeological project is doing in their area and what the results are. For example, ARPA gives federal agencies responsibility for public awareness.

Almost all archeology is now public archeology in one form or another. In the formal use of the term, McGimsey's statement that there is no such thing as private archeology has come true. The exception might be privately endowed museums and universities.

BJL: As your career has shown, one very important part of the public for archeology is the large cadre of amateur archeologists. Could you tell us why you think it's important for professional and amateur archeologists to work together and share your thoughts about how we can best do so?

HAD: Because there are a whole lot more of them than there are of us. And that means that they own a LOT of archeological sites. Or they know where they are because they collected arrow heads in a special place while their Dad was fishing. One thing I noticed when I lived in Iowa and the same holds true for Arkansas, both rural states, is that there were in both states a lot of rural postmen who were members of the state archeological society. They all said their "customers" who knew of their interest in Indian artifacts would tell them when they found arrow heads or bones when they were working their fields. And personally, I have found that I have made lifelong friends.

Amateur archeologists, at least in small rural states, also more often know their legislatures personally. The Arkansas Archeological Society sent specific information to its members when the legislation creating the Archeological Survey was going through the State Legislature; many Society members contacted their local legislators; had a mid-morning cup of coffee with them at the local café. In our case, McGimsey was the only professional archeologist in the state, and these voices of "the public" were really responsible for the passage of the Act creating the Survey and for the passage of the bill providing the money. And they still act in this capacity when they are needed.

Amateurs come with many levels of interest, many misunderstandings about the past, many faults in their knowledge. Some will only come to meetings; some love to work in the lab and are happy to spend time washing or numbering rocks, provided there is someone to talk to and answer their questions. Some will only participate if there is field work, some have very useful jobs (like computer graphics, or public relations and marketing); a friendly and knowledgeable lawyer might come in handy some time too. We have always seemed to attract nurses, which is useful in the field!

BJL: Do you see any downside to working with amateurs?

HAD: There are, of course, some "amateurs" who are died-in-the-wool collectors, who buy and sell artifacts, who want to know where the good sites are that the professionals know of because the professionals must know there is neat stuff there. Hard to impossible to change them, although I must say that I think that the passage of [the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act] NAGPRA has slowed the looting of graves in eastern Arkansas.

The key in developing relationships with amateurs is to maximize the time you and they have for programs or activities. For example, one or two professionals can take a group for a survey project where you, the professional, can talk about why and how a survey is done. The following weekend, you can invite this group to your lab and teach them what is involved in the record keeping and processing of the items they found. They learn; you get a lot of lab work done. Or have an arrangement that a school group come to your excavation project at a specific time and get a tour and talk about what is going on, what you are looking for, how you do the excavation so carefully, and why you are digging where you are. Always have a brochure about the site and the project for these kids to take home and talk to the parents about what they learned.

BJL: That makes me think of what many professional archeologists say about working with amateurs, which is that it takes a lot of time.

HAD: All of this develops your patience. One-on-one work with amateurs is time consuming; a more efficient way might be to write a grant proposal for a project that involves amateurs but also provides funds for one professional to devote half or full-time to the project. A project involving development of an exhibit for a local museum would not only be a great way to get information about a local archeological project to the "public" but also be a lesson for those amateurs involved in development of the exhibit in communicating research information to the "public." And for the archeologist involved it could be a lesson in communicating by writing in English and not in archeological jargon. It is better to say in an exhibit label that "This is a stone [NOT a lithic] tool made somewhere between 1000 and 1500 BC."

BJL: Would you tell us about the Arkansas training program?

HAD: The training program was started in 1964, when it lasted for nine days (so as to cover two weekends), and was a huge success. Sixty people participated, and as has been our experience over the many years, it poured rain the first day and a half. This was before the Archeological Survey was created, but we were able to use graduate students from the university to help with instruction. The dig was at three sites on the White River near the town of Mountain View. We were lucky to have the editor of the local paper and a member of the school board to help us with logistics. In essence, the high school building was turned over to us for male sleeping, lectures, and lab, and one of the school buses was assigned to us, driven by the Society member who just happened to be on the Mountain View school board. The females were able to take advantage of a rural southern addition to many public schools, and that was a separate building specifically designed for teaching home economics: a full kitchen, two bedrooms, living area, etc.

There were never 60 people in the field at one time, because some were in seminars, or working in the lab. We stipulate that no one could dig without having first attended "orientation" which is given every morning that new people arrive. This provides members with information about the site and its place in Arkansas prehistory. Members are introduced to basic excavation techniques and given a review of the forms they will be required to fill out while they are digging.

We continued this kind of a program at different sites around the state until 1972, when we complicated our lives considerably by creating a certification program. We expanded the length of the program to 17-19 days and 3 weekends. This was to accommodate the seminars that members are required to take for advancement through the certification program. The program is now considered a joint one with the Archeological Survey providing the training, and the Society providing most of the logistics, which includes arrangements for a camping area and all facilities that requires. If possible the Society Committee also makes arrangements for a place for lab, lectures, and seminars to be held.

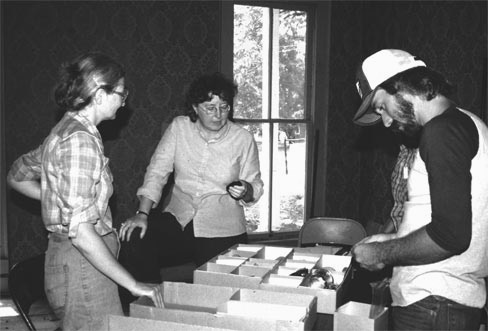

|

Hester Davis discusses artifacts with two participants in the Training Program, 1999. (Courtesy of Hester Davis.) |

BJL: What is the underlying purpose of the program and how does it work now?

HAD: The basic philosophy behind the certification program is to provide "goal oriented" members with an opportunity to be certified in three levels of "expertise." Each member is given a "Log Book" (this program was totally Bob McGimsey's idea, and the Log Book reflects his time in the Navy). There is a $12.50 one-time registration fee for the certification program and each member must keep track in the book of the time in the field, in the lab, and in seminars, and have the signature in the Log Book of the instructor or supervisor each day.

There are three levels of participation: Level One requires basic instruction in three areas—excavation, lab work, and surveying. Forty hours in the field or the lab and one seminar—this results in the awarding of a Certificate as a Provisional Site Surveyor, Provisional Crew Member, or Provisional Lab Technician. Each seminar is scheduled for five half-days (Monday through Friday). At least four seminars are taught each of the five days.

Level Two requires additional work and more responsibility to become a Certified Site Surveyor, Certified Crew Member, or Certified Lab Technician. For each of the Level Two certificates there is also a requirement for attendance at a number of advanced seminars. Once all six of these certified categories have been completed and signed off on, the member will/can be certified as a Certified Archeological Technician.

And then there is the final award, Certified Field Archeologist. There are but two requirements: (1) has received the Certified Archeological Technician award; and (2) has designed and carried out a research project, and it is published in a refereed archeological journal, book, or monograph (including The Arkansas Archeologist). The Director of the Arkansas Archeological Survey must have the final sign off on all the categories.

BJL: Does the program work as well as you'd like?

HAD: The principal problem with the program is that it takes a long time for an individual to get through the categories, particularly the last one. When you can only come to the dig for your week's vacation, accumulating the required field experience takes time. Only three people have completed and received the final award, that of Certified Field Archeologist; five others have done everything except complete the final written and published report, and one of those is working on his final report.

There are around 350 people who have, over the years, signed up for the Certification Program, but many of those dropped out after a year or two. Mostly these have been people from out of state, as they find a local or closer state society now giving training programs. As I have said, many people seem to want the information more than the certificate, which is fine with us.

One of the best results of the program for Arkansas is that scattered around the state are experienced, trained people who have attended the program for many years—public archeologists, if you will, who can be called upon by the Survey Station Archeologists for help. This is particularly obvious when there is some kind of an emergency. The main advantage we have in administering this program is that we have a large staff of professional archeologists with the Survey that we can call upon to provide the supervision and training. However, after 45 years, we also now have a number of Society members who can and are used as supervisors in field and lab, and can teach an occasional seminar.

There have been changes and modification over the years but registration for the training program each year (the Society Dig as it is called colloquially) still runs each summer at around 75 to 80.

BJL: You've had an influential career in so many ways. You've raised awareness and took effective action against site destruction; you've successfully argued for a high degree of professionalism among archeologists; you've led by example in involving the public in archeology. What's the most unexpected or most rewarding thing that you've accomplished?

HAD: The most unexpected was being appointed by President Clinton to the Cultural Property Advisory Committee, there is a large official looking framed statement, full of legal "testimony" as to my "integrity and ability," etc., etc. signed by the President himself although not in my presence, nor did he appear at the time I took the required oath to shake my hand. I had served on the Board of the US/ICOMOS, and am a member of the World Archaeological Congress, but most of the other people on the Committee at the time were much more familiar with trafficking of artifacts from some foreign country into the U.S. than was I. However, I learned a great deal over the six years I served on that committee.

|

Hester Davis is surrounded by piles of reports during the time she was reviewing reports for the State Historic Preservation Officer. (Courtesy of Hester Davis.) |

BJL: Looking back on your career, can you share observations or advice for the next generation of public archeologists?

HAD: Let's see. If you have an interest in making things move in the profession, volunteer to work on a committee or two in your state society organization where you think you can help with ideas or through your organizational experience. Or do that for the SAA or the SHA [Society for Historical Archaeology]. As I look back, I think I probably raised my hand too often when a Chair or President said "is there anyone who would like to tackle this problem for us?" Don't be shy to stand up at the SAA business meeting and make a comment or present an idea about something that has been discussed. Learn how the SAA committees work, and particularly their relationship with the SAA Board.

Above all, be vigilant! Particularly when information is circulated about something that has been or will be introduced in Congress. All the professional organizations have something equivalent to "Government Affairs Committee." Ask the main office of the SAA to be on the free mailing list to receive the information about bills introduced, or actions taken in congressional committee. Pay attention to new suggestions that may affect what you are doing or what the profession should be doing. Actually I think that the vast majority of archeologists are doing this now, as opposed to 40 years ago when their heads were buried in their research!