Article

Canadian Historic Sites and Plaques: Heroines, Trailblazers, The Famous Five(1)

by Dianne Dodd

In the late 1950s the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada (HSMBC), chaired by prominent Canadian historian Donald Creighton, dismissed a proposal to create a national historic site at the homestead of Adelaide Hoodless, domestic reformer and one of the founders of the Women's Institutes. In a period when the nationalist discourse went unquestioned, the board simply did not see a conservative feminist making a historic contribution that warranted investment in a site. Like most Canadians of their time, board members saw the purpose of historic sites and plaques as evoking national pride by recognizing the largely white, male elites who forged a nation from a disparate group of British colonies, resisting the pull of the American republic to its south. Of course, there is no such consensus on national history today, as the voices representing class, racial, and gendered identities have gained general and academic respectability. These voices have been slower to gain acceptance in the realm of public history(2)—in many national museums, historic sites, and interpretative programs, the nationalist discourse is still valued.(3)

The recent interest in public history among academic historians has resulted in a growing body of literature, including a few case studies on Canadian women that provide rich analyses of early female history-makers, while illuminating the contested terrain of historic memory. Colin Coates describes the ambivalent admiration accorded the dramatic, military-style heroics of Madeleine de Verchères during the 17th-century French-Iroquois wars.(4) Cecilia Morgan and others have documented the early women "amateur" historians who deliberately added a feminist sub-text to the nationalist discourse by highlighting Laura Secord's brave walk through dangerous terrain to warn the British of an impending American attack during the War of 1812, a defining moment in Canadian history.(5) In a similar vein, Katherine McPherson analyzed a 1926 memorial erected by the Canadian Nurses Association to remember 49 nurses who died in the Great War. She describes the compromises women had to make to place their monument in the Canadian Parliament buildings on Parliament Hill including juxtaposing the modern uniformed nurse against her religious predecessor and expressing nurses' wartime heroism in generic, maternal terms.(6) Linda Ambrose has also looked at the role of the ever-present Women's Institutes, which were active in numerous, less controversial forms of remembering.(7)

This paper adds to two preliminary studies of Canadian women commemorated in a federal commemorative program guided by the advice of the HSMBC (the board) and administered by Parks Canada.(8) It provides a snapshot of all 126 designations relating to women beginning with the HSMBC's establishment in 1919, up to 2008—these make up 6 percent of a total of 1,942 commemorations in this program.(9) The author draws upon the board's minutes, some Parks Canada records, plaque texts, and her own experience as a Parks Canada historian to shed light on the disparate alliances of Canadians who negotiated the inclusion of women into the national story. What do these historic markers tell us about what constitutes an appropriate model of feminine heroism for an audience of plaque readers and historic site visitors at the national level? Given the strong emphasis on warfare in public history and historical consciousness,(10) it should come as no surprise to find that women's first entry into the world of national commemoration was through an elite military-style heroine. Reflecting similar trends in several comparable surveys done in the U.S.,(11) Verchères was followed by founders of women's organizations, nuns, elite literary women, nurses, pioneers, sports figures, and even some controversial feminist leaders, among them the Famous Five who challenged the Canadian constitution to recognize women as legal persons and who enjoyed a particularly enduring popularity.

In Canada, as in American and Australian contexts, there is an apparent reluctance to accord hero status to individual females and a tendency to memorialize women collectively as pioneers, nurses, workers, or wives.(12) Public memorials, particularly in the case of women whose entry was contested, appealed to overlapping but often quite different audiences. Revealing a degree of ambiguity,(13) these commemorations leave room for the celebration of traditional femininity, laced with the bravery and civic contributions that ensured they fit well into an official, commemorative program at the national level, as well as the more disputed creation of feminist icons.(14) Not surprisingly, many of these commemorations, especially in the early years, celebrated elite Anglo-Celtic or French women—the 'women worthies' of the early historiography on women. However, the paper concludes by examining recent trends in a program that is moving toward greater diversity, and tentatively explores discrepancies between commemorative themes and academic interest, asking whether women have a different purpose than men in their commemorative initiatives.

The paper also takes a closer look at the very small number of federally designated women's history sites in Canada. Initially, there were very few in the federal program, as women's achievements were often marked with a "secondary plaque" instead of a site. Some historians see the program's focus on commemorative plaques as symptomatic of a weak federal role in the more serious business of preserving and developing historic sites;(15) however, it is clear that these plaques offered women an entry into commemoration and were highly valued by proponents. Once women's history became a strategic priority in the 1990s, the number of sites increased significantly. Thus, the Canadian experience seems to confirm Dolores Hayden's observation that despite restrictive criteria, women's sites can be identified and developed when the political will exists.(16) Notably, it was through the initiative of local groups that Parks Canada brought women's history sites, already developed and interpreted by groups such as the Women's Institutes, into its network of historic sites. None of these women's history sites are directly administered by Parks Canada.

The Federal Commemorative Program: HSMBC and Parks Canada

The HSMBC, a politically appointed and regionally balanced board, is the official advisor on commemoration at the national level in Canada. It has limited resources and no staff, except for a small secretariat, and its programs are administered by Parks Canada, under the Minister of the Environment. Designations are usually initiated through a public nomination process, although board members may also bring forward a proposal or ask for a study in a specific area. Then Parks Canada historians write, or oversee the production of, a submission report, which is considered by the board at their twice-yearly meetings. Guided by its criteria(17) of national significance in evaluating all nominations, the board makes a recommendation to the Minister, and if approved s/he announces the designation as a nationally significant person, event, or site. Naturally, the board is influenced by the historiography in place in any given period and public interests.(18)

Historian Yves Yvon Pelletier has characterized the board, in its first 30 years, as a Victorian Gentlemen's club that promoted an imperialist view of Canadian history with numerous designations commemorating the War of 1812.(19) At that time, its membership was dominated by serious "amateur" historians such as John Clarence Webster, a retired physician, who became a historian and served as a long-time HSMBC member, including chairman for several years before his death in 1950.(20) With his wife, Alice, he collected artifacts and contributed substantially to the development of the New Brunswick Museum and several historic sites.(21)

In the 1950s, professional historians such as Donald Creighton and A.R.M. Lower exerted a stronger influence. However, with minimal budget and, before 1950, an insecure mandate,(22) the HSMBC often turned down projects involving acquisition or preservation of buildings, focussing on commemoration and its role in deciding national significance. By the 1960s and 1970s, as historian J.C. Taylor has noted, Parks Canada and larger government players undertook huge renovation and reconstruction projects, many of them military, such as the Fortress of Louisbourg.(23) In the 1990s, Parks Canada identified three strategic commemorative priorities: women's history, ethnocultural communities' history, and Aboriginal history.

Still, Veronica Strong Boag, former Historic Sites and Monuments Board member and historian of women and children, found the national body slow to respond to pressures from community groups and the new historiography.(24) One critic has describe the new priorities as little more than a "plaquing program,"(25) in part because of weak federal legislation that has no "teeth" to ensure protection of a site, once designated.(26) Indeed, given the considerable political and financial resources sites require and the underfunded state of the program, there are few Parks Canada administered sites—most are run by community groups or other levels of government. As well, of the three categories of designations, persons and events (in which the majority of commemorations relating to women fall) are marked only with a historic plaque. Sites alone afford owners access to Parks Canada cost sharing support—when available—and technical expertise in order to preserve or improve a building, and/or develop interpretation.

Despite its imperfections, a federal designation holds real significance, especially for previously excluded groups. All designations are registered on the List of Designations of National Historic Significance, and are plaqued at an appropriate location. Particularly in the case of the three strategic priorities, designations are often featured on the Parks Canada website as well, and sites, as mentioned, are eligible to apply for financial and technical aid and become part of Parks Canada's family of National Historic Sites.

The Women's History Designations

When women's history became a strategic priority along with Aboriginal history and Ethnocultural Communities' history, in the 1990s, the board gradually became more attuned to gender issues. Although Strong-Boag has recently remarked that it is not clear "that the commemoration of women was an equal beneficiary" with the other strategic priorities, the number and diversity of commemorations continue to expand.(27) From a very small number, the commemorations subsequently grew as staff and board members drew on the growing historiography on women's history. National and, later, regional workshops were held at which board members, staff, invited experts in women's history, and grassroots activists mapped out a strategy to improve the commemoration of women.

In its early years, the HSMBC showed minimal interest in projects concerning women and/or those put forward by women, although women's commemorations did receive a boost when the board decided to erect "secondary plaques," creating a list of what it called eminent or distinguished Canadians.(28) This accelerated the number of "person" designations in which the majority of women's commemorations are now found. In the 1930s, when Parks Canada experienced a period of growth due to an influx of money from the Public Works Construction Act (PWCA) directed at reducing unemployment rates, women's designations did not receive any of the funds.(29) However, at least two of the PWCA projects enjoyed leadership from female heritage activists.(30) The principal activist, researcher, and fundraiser for the preservation and historic reconstruction of Port Royal, the 1605 settlement of Samuel de Champlain, was American Harriette Taber Richardson, who was designated for her contributions in 1949.(31) At the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site, Katharine McLennan, daughter of Senator and prominent Cape Breton industrialist J.S. McLennan, was named honorary curator of the new Louisbourg Museum built in 1936.(32) A recent virtual exhibit on women at the New Brunswick Museum adds to our knowledge of these important early women collectors and preservationists.(33)

Certainly, the distinguished gentlemen of the HSMBC were happy to accept support from women. In 1943, they thanked the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa for making arrangements and serving tea at the plaque unveiling ceremonies for British explorers who participated in the conquest of the Canadian Arctic, 1497-1880, and for Dominion Archivist Douglas Brymner.(34) When the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Toronto solicited the board's support in its efforts to preserve Fort York in December 1920,(35) however, none was forthcoming. Ten years later, the board expressed its enthusiastic approval upon learning that the society members "desire to undertake the erection of this memorial themselves."(36) In 1953, the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa asked the board for support in renovating the old workshop of Colonel By, the builder on the Rideau Canal, but the request was deferred and no funds were allocated.(37)

Of the 126 designations relating to Canadian women in this federal program made from 1919 to 2008 (6 percent of 1,942 designations) 27 are sites, 66 are persons, and 33 are events.(38) The small number of designations compare to similar programs elsewhere. For example, in 1989, 360 out of 70,000 sites listed in the National Register (4 percent) are related to women; and, only in 2002, only 8 women were found in a survey of 252 memorials in the town of Lowell, Massachusetts.(39)

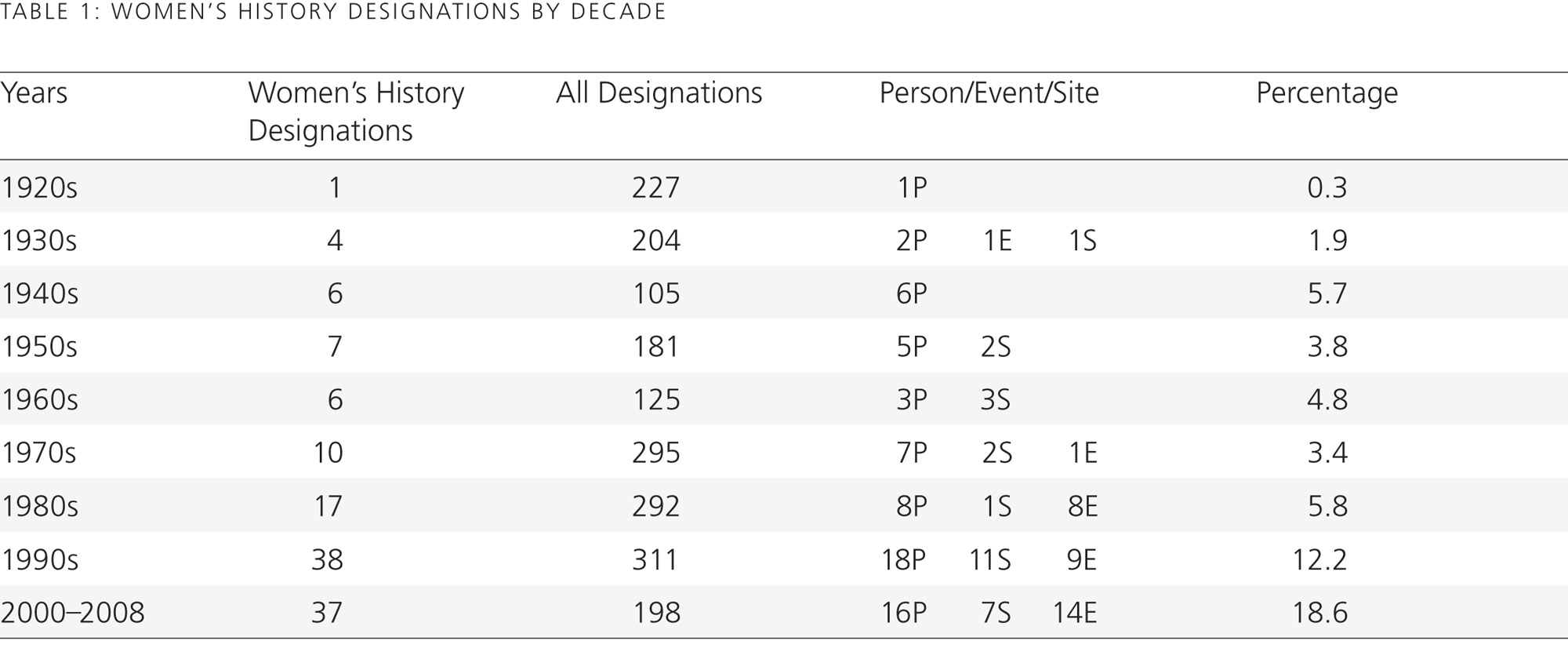

Table 1 shows a breakdown of the designations by decade with categories of person (P), event (E), or site (S) also noted. From only one designation in the 1920s, and relatively few from the 1930s to the 1960s, the numbers began to rise substantially in the 1970s, due no doubt to the second-wave feminist movement and increased interest in women's history. By the 1990s, there was a larger jump forward as women's history became a strategic priority.

|

Table 1. Women's History Designations by Decade. |

In the 1920s, the only women's history designation out of a total of 227 was of Madeleine de Verchères. In the 1930s, there were four designations related to women out of a total of 204, representing 1.9 percent. The decision to erect secondary plaques(40) resulted in recognition of many prominent individuals. Included among them were a few women, such as the internationally acclaimed opera soprano from Quebec, Emma Albani, and the first of the suffrage/Persons Case leaders, Louise McKinney. In the 1940s, there was a fall in absolute numbers of designations, probably because the board suspended its activities for several years during World War II. The percentage rose to 5.7 however, as there were six designations that related to women out of a total of 105, perhaps reflecting women's greater visibility in war-related work. In the 1950s, total designations approached pre-war levels, but with only seven designations devoted to women out of a total of 181, the percentage dropped to 3.8. In the 1960s, the percentage of women's history designations rose to 4.8, or six out of a total of 125 designations.

In the 1970s, the overall number of designations rose considerably to 295, but with only 10 of these relating to women, the percentage dropped to 3.4. In this decade Parks Canada expanded its programs, acquired new staff, new sites and participated in historic reconstruction projects. For example, larger political priorities pushed Parks Canada to undertake reconstruction of one-quarter of the old town and the Fortress of Louisbourg as a Canadian centennial project (1967) and to create tourism jobs in the face of a declining coal industry in Nova Scotia. With large sums being spent, Parks Canada, and even more so the board, took a back seat.(41)

In the 1980s, the number and percentage of women's history designations rose, with 17 out of a total of 292, or 5.8 percent, returning to World War II levels. Nine of these were persons and one was a site. The rest were "events," a category increasingly used to capture women's collective achievements.(42) For example, when board members decided that Margaret Polson Murray, founder of the women's service organization, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE), was not of national significance, because she was involved with the organization an insufficient length of time after founding it, they decided to commemorate the organization instead.(43) In the 1990s, following a series of women's history workshops, the number of designations relating to women rose to 38 out of a total of 311, or 12.2 percent. Up to 2008, there have been 37 out of a total of 198 designations relating to women, or 18.6 percent.

Military Heroines, Religious Women, and Feminists

Are there trends in these 126 commemorations? The earliest commemoration of a woman, in 1923, was the military heroine Madeleine de Verchères. Her plaque text reads—

In 1692, Madeleine de Verchères, then only 14 years of age, alone in Fort de Verchères with her two young brothers, an old servant, and two soldiers, took command and defended the post successfully for eight days against a war-party of Iroquois.(44) |

In the literature on popular historical consciousness in Canada and elsewhere, it appears that many "consumers" of public history are not particularly receptive to women's history as a topic, certainly vis-à-vis such perennial favorites as warfare.(45) Thus, women's commemoration began with a woman who captured the cautious admiration of historians and the public alike for momentarily stepping out of her traditional feminine role to assume a military posture, albeit a defensive one. Her persona uneasily juxtaposed male-like traits of heroism and bravery with feminine virtues of domesticity and passivity. The HSMBC plaque was unveiled in 1927 and placed at the site of an existing monument, created by noted Canadian sculptor Louis-Philippe Hébert. It had been erected in 1913 through the efforts of Governor General Lord Grey and the parish priest of the town of Verchères, Abbé F.A. Baillargé. Verchères designation also reflects the Canadian historiography of the 1920s, in which Canadians were positioning the Great War as a catalyst to Canadian political autonomy vis-à-vis Britain.

Interestingly, Verchères' English-Canadian counterpart, Laura Secord (1775-1868), who played a similar iconic role in mixing nationalism with feminine bravery, was not designated (as a person) until 2002, following a nomination from the Niagara Parks Commission. The board had received a proposal in 1934 to acquire Laura Secord's home in Queenston, Ontario, but deferred a decision. Although during the 1930s most building designation requests were turned down, the board was undoubtedly also influenced by the historiography of the period. Academic historian W.S. Wallace was leading a campaign to discredit Secord as a factor in the outcome of the Battle of Beaver Dams in the War of 1812 and generally to distance the emerging historical profession from amateur women's historians, led by Emma Currie and Sarah Ann Curzon, who had taken up the Secord story.(46) The plaque text, drafted in 2004, is careful not to overstate the military claims, but nonetheless acknowledges Secord's bravery and her importance to women's history—

This celebrated heroine of the War of 1812 is a renowned figure in Canadian history. Determined to warn the British of an impending American attack on Beaver Dams, Secord set out from her home on June 22, 1813, on a dangerous mission. She travelled alone for over 30 kilometres behind enemy lines, struggling to make it to the De Cew farmhouse, where she informed Lieutenant FitzGibbon about the American plan. Later in the 19th century, a first generation of women historians championed Secord's courageous deed with the goal of uncovering and popularizing women's contributions to the history of Canada.(47) |

Similarly, the board deferred action on proposals in 1934 and again in 1955-56 to fund restoration of Verchères's seigneurial home in Ste. Anne de la Perade, near Montréal, Quebec.(48) Although Verchères was less an object of feminist hero-making, her luster faded by the 1920s when new records emerged to illuminate an adult life that detracted from her value as a heroine.(49) Since the 1930s, both Verchères and Secord have been largely relegated to history textbooks for young children.

The military theme came up again in the commemorative program where we find that World War I nurses were the first nurses, and among the first women, to be commemorated. The HSMBC in 1982-83 recognized Major Margaret Macdonald, Matron in Chief of the nursing service of the Canadian Army Medical Corp during World War I, and Matron Georgina Pope, the first matron of nursing services. In 1994, the HSMBC decided, in its discussions relating to the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of D-Day, to designate women's entry into the Canadian military in World War II as an event of national historic significance.(50) Although it was not the three associations of the women's services (army, navy and air force) who brought the nomination to the board, they enthusiastically embraced the commemorations. While it is not uncommon for women to be designated in relation to a broader study of a larger historical phenomenon in which they had participated, that was not always the case. For example, the 48,000 war brides who immigrated to Canada after marrying servicemen stationed overseas during World War II were designated in 1996 after the Victoria War Brides Association brought the topic to the board's attention.(51)

Popular Heroines

Besides military-style figures, other popular heroines have been designated, including exceptional female athletes who achieved some popular attention in the aftermath of the suffrage victory and the entry of women into Olympic competitions. The plaque text for the Edmonton Grads notes—

In a twenty-five year history, beginning in 1915, the women of the Commercial Graduates Basketball Club, coached by Percy Page, achieved world recognition. This amateur squad, made up almost exclusively of graduates and students of McDougall Commercial School in Edmonton, held the provincial crown for twenty-four years and the Canadian title from 1922 to 1940. Undisputed North American champions, the Grads competed in exhibition play at four Olympic Games (women's basketball was not then recognized as an Olympic sport), defeating all European challengers. The team was disbanded in 1940.(52) |

Both the Grads and Fannie (Bobbie) Rosenfeld, a hockey player and a member of the "Matchless Six" (so named for winning numerous medals at the 1928 Olympics, when Canadian women competed in track and field events for the first time), were brought to the board's attention as a result of board member Dr. J. Edgar Rea's study, Canada's Sporting History, in 1976.(53) In the era before professional—primarily male—sport teams monopolized fan and media attention, these women had become household names. Often they invoked national pride, as reflected in the 2005 designation of the 1954 swim across Lake Ontario by Marilyn Bell. This event designation followed a nomination by the Boulevard Club in Toronto, where she had trained. Her plaque text reads—

On the evening of September 9, 1954, 16-year-old marathon swimmer Marilyn Bell became the first person to swim across Lake Ontario. Racing unofficially against the heavily favoured American swimmer Florence Chadwick, Bell endured eels, high winds, and frigid waters for almost 21 hours to complete her world-record-breaking 51.5-kilometre swim here. Her courageous achievement won unprecedented attention both at home and abroad for the sport of marathon swimming in Canada. Bell's swim demonstrated that women could compete in even the most gruelling sports and fostered immense national pride.(54) |

Several American authors have noted the many generic tributes to pioneer mothers in the United States,(55) and pioneer women were also popular in Canada. In 1982, Marie-Anne Gaboury, the first "White" woman in the west who arrived in 1806 was designated with her husband, Jean-Baptiste Lagimodière. She is briefly mentioned in his plaque text largely because the local Saint Boniface Historical Society requested it.(56) Such women seemed to combine feminine skills and a nation-building, pioneer spirit with a quiet, non-threatening challenge to gender boundaries. In the 1970s, well-known Canadian pioneer writers Susanna Moodie and Catherine Parr Traill were designated, and even pioneering nurses held a strong appeal. The Newfoundland Outport Nursing and Industrial Association (NONIA), which sent nurses to isolated outport communities in Newfoundland, was designated in 1998. The board emphasized the nursing aspect of their story over the role that female organizers played in creating a still-thriving craft business—

Outstanding among nursing organizations serving isolated communities across Canada, NONIA brought professional health care to Newfoundland's outports. Women reformers founded the organization in 1924 using the production and sale of handicrafts to finance their work. Besides training lay midwives and delivering babies, British-trained nurse-midwives pulled teeth and transported the sick along hazardous routes to distant hospitals. Although its nursing service was incorporated into Newfoundland's health system in 1934, NONIA remains a leader in the promotion of handicraft production.(57) |

After recommending designation of a Red Cross hospital in Wilberforce in 2002, a board committee suggested, "Parks Canada encourage public nominations of Red Cross outpost nurses for consideration by the Board."(58) Later, La Corne Dispensaire in Québec was also designated, another site exemplifying pioneer women who provided nurture to isolated populations while sometimes challenging local authorities. The outpost nurses were among the first women to drive automobiles and live independently from fathers and husbands. Indeed, a letter from the local Bishop giving the nurses permission to wear pants, thus overruling the objections of the local priest, is proudly displayed at the La Corne site.(59)

Female Religious Communities

American historians have noted that among the few sites relating to women, there are many house museums. Many of these such as the Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site in Hyde Park, New York could be called "Great Woman Houses."(60) However, the Canadian historic sites network is somewhat richer in motherhouses, convents, hospitals, and schools than in the homes of distinguished women,(61) a built environment legacy left by female religious congregations. Widely recognized as builders of communities and pioneers in health, charity, and education, nuns are the exception to the general invisibility of women in history and commemoration.(62) Even in the United States with a proportionally smaller Catholic population than Canada's,(63) nuns are nonetheless evident in public memorials.(64) Originating primarily in Québec, women's religious congregations later expanded across the country and played a major, if quiet, role in Canadian history.

Although religious women showed great modesty in telling their own stories—as indeed most women have—their obedience and loyalty to church hierarchy often masked a quiet assertiveness. Symbolized in the habits they once wore, their religious devotion and "marriage" to the church made them paradoxically both maternal and asexual. Sheltered from many of the restrictions women experienced in patriarchal society, they owned and managed large properties, hospitals, and schools, raised funds in the community and negotiated with public officials.(65) Thus, leaders of female religious congregations proved acceptable female subjects with the board, proponents, and communities themselves. In the 1970s, Sainte Marie M. D'Youville, who founded the Grey Nuns in 1747, was designated as a person of national historic significance. She was followed a decade later by Marguerite Bourgeoys, who founded the Congregation Notre-Dame in 1658. In 1988 seven female religious communities were designated as national historic events in recognition of their work in health, education, social welfare, and culture.(66) This followed a 1981 board request to designate a specific monastery, and a subsequent study on "the contributions of the major religious orders active in Canada" to provide comparative context. As well, several male orders were designated.(67)

Women's religious communities built most of the early national historic sites relating to women. Given that most were designated for their architectural and/or historic association with no emphasis placed on the contribution of women, we might call them "accidental women's history sites." For example, the Hôtel-Dieu in Quebec City was designated in 1936 because it was the first hospital in North America, north of Mexico, although the plaque did acknowledge the founder and the Augustinian nuns who "ministered to alleviate human suffering" for more than three centuries.(68) The former Grey Nuns Convent in St. Boniface, Manitoba came into the historic sites system in 1958 through the efforts of HSMBC member for Manitoba, Mgr. D'Eschambault, who wanted to develop it as a museum for the St. Boniface Historical Society.(69) (Figure 1) Here, the nuns' work, especially in health care and education was subsumed under the larger commemorative theme of the French Catholic presence and survival in Western Canada. St. Ann's Academy, a Catholic girls school, motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Ann and Victoria, a British Columbia landmark, which was managed by the Provincial Capital Commission, became a national historic site in 1989 for its contribution to the cultural and educational life of western Canada.(70) At Hôtel-Dieu, the Augustines recently successfully nominated the achievements of their own congregation as an "event" of national historic significance, and since that time several more congregations have been designated, including the Misericordia Sisters and the Religious Hospitallers of Saint Joseph.

|

Figure 1. Grey Nuns Convent, Saint Boniface, Manitoba, Parks Canada, 1986. (Courtesy of Parks Canada.) |

Although the links are seldom drawn in a Canadian historiography divided along language lines, these religious women had counterparts in the English-speaking, Protestant community. Recent designations, most of them as events, have commemorated women who did similar work in healthcare, education, and social work. Indeed, in a recent analysis of women's commemorations, it was found that the bulk of them were congregated in community work.(71) The national women's history workshops held in the early 1990s recommended framework studies in key, well-documented areas of women's activities—areas that would be amenable to commemoration: politics, healthcare, work, education, and science/technology. Staff, which by this time included historians well versed in the new social history, drew on the growing academic literature on women. The addition of noted historians of women's history, Margaret Conrad and later Strong-Boag, on the board also meant that women's history was more explicitly represented.

Numerous designations followed, reflecting both a conservative celebration of women's collective achievements in traditional roles such as nuns, teachers, nurses, and charitable ladies, and the creation of feminist icons who broke down gender barriers. In health care, the Victorian Order of Nurses was designated (event) as well as five nurses' residences (sites). The achievements of important women's organizations, including the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA), the Canadian Woman's Christian Temperance Union (CWCTU), and the Fédération Nationale Saint-Jean Baptiste (FNSJB), were commemorated as events. Designations of elite women whose careers crossed the delicate divide between social reform and feminist-inspired politics included Helen Gregory McGill, a judge who pioneered the development of family law and family courts, and Marie Lacoste Gérin-Lajoie, who founded the FNSJB which championed both women's rights and social causes such as improved infant health. Always mindful of the national criteria, historians emphasized these women's roles as nation builders who erected some of the building blocks of the emerging post-World War II social welfare state.(72) As well, the event designation, "Winning the Vote," led to a virtual exhibit being created as well as interpretive panels being placed at the Walker Theatre, a national historic site where the famous Mock Parliament, a play starring prominent Manitoba suffragist and author Nellie McClung,(73) was held, marking a milestone event in the suffrage campaign.(74) Walker Theatre had been designated in 1991 largely for its architectural history. Although its association with important suffrage and labor meetings was later added to the plaque text, it says little about suffrage and nothing of Harriett Walker, wife of the theatre's owner and a former actor who produced the play—

The Walker is an excellent example of an early Canadian theatre designed for serious dramas, operas and musicals. Opened in 1906, it was run by C.P. Walker, whose New York connections brought in international stars and a dazzling array of productions. Nationally important political rallies held here included meetings of the women's suffrage and labour movements. Designed by Howard C. Stone, the Walker was notable in its day for such features as fireproofing, the arched ceiling resembling the Auditorium Theater in Chicago, and the inexpensive "gods" section of seating.(75) |

The Famous Five/Persons Case: An Enduring Symbol

The "Persons Case" was a successful appeal to Canada's highest court that clarified in 1929 the legal personhood of Canadian women and set a precedent for constitutional reform.(76) This removed the last barrier to full political equality and permitted women to be appointed to the (non-elected) Canadian Senate. Several commentators have noted the lack of attention accorded to the Persons Case in public remembering. Strong-Boag notes that from 1929 to the late 20th century, the Famous Five were only recognized by one bronze plaque erected by the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs outside the Senate Chambers of the Parliament Buildings in 1938. Further, Calgary businesswoman Frances Wright was motivated to establish the private Famous 5 Foundation when she discovered the gravesites of the five women did not mention their achievement.(77) However, they were not entirely forgotten. Although less well known, there were historic plaques to all five women erected by Parks Canada through the recommendations of the HSMBC. They note both the Persons Case and other achievements in relation to the women's movement.

Louise McKinney was the first of the five signatories to the Persons Case to be designated, in 1939. The Leeds and Grenville County Historical Society initially nominated McKinney in hopes that her plaque would be placed at her birthplace in Frankville, Ontario. However, it was later decided to place the plaque in Claresholm, Alberta where she lived most of her adult life and was active in community and political life. Her Alberta community was keen to promote this local heroine. Schools and businesses closed for the plaque unveiling ceremony at which prominent local, and some provincial, dignitaries presided.

While feminist sentiments were quietly present, most local boosters stressed McKinney's service to her community and expressed their pride that Western Canada had taken a lead role in the suffrage movement. The ceremony also reflected the community's aim of using a commemorative moment to instill the values of citizenship in the local populace. McKinney's feminism took second place at the ceremony. Her plaque text was revised in the 1970s to make it bilingual (French and English) in accord with the government's new policy on bilingualism. It does not acknowledge McKinney as the first women elected to a legislative house in the British Empire because later guidelines discouraged recognition of "firsts" per se. However, the community initially considered this important.(78) Her plaque text reads—

Born in Frankville, Ontario, a graduate of Ottawa Normal School, Louise McKinney, with her husband and child, settled at Claresholm, Alberta in 1903. An active member of the WCTU and the IODE and a tireless worker for social causes including temperance and women's rights, she fought hard for female suffrage, (which was granted in 1916), before entering provincial politics. Having served one term (1917-21) as an elected member of the Legislature, she became an active member of the group of five whose appeal to the Privy Council earned for women the right of entry to the Canadian Senate. She died at Claresholm.(79) |

During the 1950s and 1960s, the other four women involved in the Persons Case were also designated as persons of national historic significance. For example, Alberta HSMBC member Joel K. Smith nominated Persons Case leader Emily Murphy in 1958. He told his fellow board members that he was conveying the wishes of the people of Edmonton, Alberta who "have under consideration a very beautiful park to be known as the Emily Murphy Park and wish to erect there a fine fountain."(80) He noted Murphy was "the first woman in the British Empire to be appointed magistrate, a capacity in which she served with great distinction," and that she was "nominated for the Senate of Canada but was not considered eligible for appointment in light of the British North America Act. With her committee of four women she argued in the Courts and went to the Privy Council in her fight for equal rights for women."(81) The plaque reads—

Born in Cookstown, Ontario, Emily Murphy moved to the Swan River district of Manitoba in 1904 and about three years later to Edmonton. A fighter for women's rights she became, as judge of the Edmonton Juvenile Court, the first female magistrate in the British Commonwealth. She led the five Alberta women through whose efforts women were legally recognized as "persons" and hence made eligible for admission to the Senate. Among the books she wrote under the pen name "Janey Canuck" were Seeds of Pine, sketches of life in Alberta, and "The Black Candle" a study of narcotics and drug addiction. She died in Edmonton.(82) |

Nellie Mooney McClung (1873–1951) was designated in 1954. The Women's Institutes were long-time promoters of Nellie's designation, reflecting her popularity as an icon of the first-wave feminist movement and the suffrage campaign. They purchased property that was part of the Mooney family's farm near Chatsworth, Ontario, erected a beautiful stone monument for the plaque and made plans for a memorial roadside park in McClung's honor. While the stonework is still standing and a roadside sign directs visitors, the park was not built. The Women's Institutes dominated the plaque unveiling ceremony where McClung's feminism was highlighted as much as her community service.(83) Her initial plaque had provided only tombstone data, as was the practice with the early, secondary plaques, however like Murphy's, it was revised to make it bilingual—

Born in Chatsworth, Ontario, Nellie Mooney moved to Manitoba with her family in 1880. As a politician and public lecturer, she campaigned vigorously for social reform and women's rights. A Liberal member for Edmonton in the Alberta legislature (1921-26) and the first female member of the CBC Board of Governors (1936-42), she was one of the small group whose efforts succeeded in opening the Canadian Senate to women. She was the author of several influential books written in the form of the Methodist and temperance literature of her day, including Sowing Seeds in Danny and Clearing in the West. She died in Victoria, B.C.(84) |

Then in the 1960s, the board recognized the remaining two members: Mary Irene Parlby whom the Board called "an able legislator…who rendered significant service in the fields of education, social welfare, and legislative reform"(85) and Henrietta Muir Edwards, "an eminent Canadian" who made an "outstanding contribution to the recognition of the status of women in Canada." Edwards had served for 35 years as convenor of the National Council of Women's committee on laws affecting women and children, and was associated with legislation for equal parental rights and mother's allowances.(86) It is not known who nominated Parlby or Edwards.

It is interesting to find the Famous Five among the very earliest designations of women, decades before Catherine Cleverdon published her important work on the Canadian suffrage movement in 1974 and the academic field of women's history began to develop.(87) What do we know about why the proponents sought recognition? Do these designations reflect the enduring popularity of the Persons Case as a feminist symbol among a small feminist cohort of the public history audience, previously ignored? Certainly the McClung case points to this, but for Murphy and McKinney, it appears that local boosters had the upper hand. The records of the HSMBC and Parks Canada are too scant to definitely answer this question, although community records might provide more information. It seems most likely however, as is so often the case with women's commemorations, that minority feminists forged alliances with more influential local figures to create these historic markers for a mix of reasons.

The achievement of full political equality remained a potent symbol of feminine historical consciousness. In 1979 an associate professor of law at the University of Toronto nominated the Persons Case as an event,(88) but the board objected that it had been sufficiently recognized through the designation of the five women responsible for it. Perhaps realizing that women's history was underrepresented, the board noted that they remained willing to consider other persons who may have played a role in the attainment of specific rights for women. They asked staff for a research report on Lady Aberdeen (1857-1939), the distinguished wife of the governor general, and key player in the founding the National Council of Women and the Victorian Order of Nurses. In specifically requesting that the plaque make reference to her charitable activities, they perhaps revealed their conception of one form of appropriate feminine behavior in a nationally significant figure. Lady Aberdeen's plaque text reads—

Raised in Scotland, in 1877 Ishbel Maria Marjoribanks married Lord Aberdeen, who was Governor General of Canada from 1893 to 1898. A formidable and energetic person, she devoted her life to promoting social causes and served for years as president of the International Council of Women. In Canada she founded the National Council of Women, helped establish the Victorian Order of Nurses and headed the Aberdeen Association, which distributed literature to settlers. Lady Aberdeen later organized the Red Cross Society of Scotland and the Women's National Association of Ireland. She died at Aberdeen, Scotland.(89) |

However, the resilient Persons Case would come before the board again and it was eventually designated as an event of national historic significance in the early 1990s following the framework study on politics that highlighted its importance. Still, the board, like most Canadians, resisted acknowledging the significance of the Persons Case as a symbol of political equality for women, beyond its legal meaning of providing entry into the non-elected Senate. This sentiment can be seen in the plaque text for Parlby, for example, which notes she was a member of the "Group of Five" a movement for, as they termed it, "admission of women to the Senate of Canada."(90) In 1979 the HSMBC noted that it was "fully cognizant of the importance of the judicial decision now popularly known as the "Persons Case," however "the essential outcome of that case was the admission of women to the Canadian senate."(91) It was not until 1997 that the board noted that the Persons Case should be designated "because the case cleared the way for the appointment of women to the Senate and because it has acquired a symbolic importance in so far as it established that Canadian women were full persons, equal to men, in both the legal and popular meaning of the word."(92)

The success, the second time around points to the importance of a developed historiography to document a case for national significance. However, it also reflects the popularity of the case in Canada, where women's history month is celebrated in October to mark the date of the final decision on October 18, 1929. It seems that removing such an odious phrase from the Canadian legal cannon as "Women are persons in matters of pains and penalties, but are not persons in matters of rights and responsibilities"(93) served as a rallying cry for Canadian women.

Especially on controversial events, plaque texts are often an exercise in compromise, and in this case the final version is careful not to give too much weight to the broader feminist view of the Persons Case as embodying symbolic significance vis-à-vis the narrower legal interpretation. After much discussion, this plaque text was approved on December 16, 1998—

The Persons Case is a landmark legal decision in the struggle of Canadian women for equality. Although most women were given the right to vote in federal elections and to hold seats in the House of Commons in 1918, their eligibility for appointment to the Senate remained in question. When five Alberta women, Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Louise McKinney, Nellie McClung and Irene Parlby, campaigned to have a woman named to the Senate, their request was denied on the grounds that women were not included among the "persons" eligible for Senate appointments under Section 24 of the British North America Act (1867). This interpretation was upheld when the matter was referred to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1928. The women appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, at the time the highest court in the British Empire. On October 18, 1929 the Committee ruled that women were included under the term "persons" in Section 24 of the Act, and were thus eligible for appointment to the Senate of Canada.(94) |

A Private Initiative to Commemorate the Persons Case

Reflecting many of the themes seen in the HSMBC/Parks Canada program was a much higher-profile, privately funded, initiative to commemorate the same women responsible for the Persons Case. It occurred at about the same time as the above discussions but was not associated with the federal program. After establishing the private Famous 5 Foundation (F5F), Frances Wright succeeded in raising large sums of money among elite Canadian women, and erected two over-life-sized monuments of the Famous Five first in Olympic Plaza in Calgary, Alberta and secondly, on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Canada's capital.(95) National level commemorations tend to generate considerable controversy,(96) and the group had to overcome a number of obstacles, including raising all of the money themselves. They also had to circumvent criteria governing statues on Parliament Hill, normally reserved for deceased Prime Ministers, Fathers of Confederation,(97) and monarchs. The F5F successfully exploited an exception to these criteria by orchestrating a unanimous vote in the House of Commons and Senate.

The unveiling of the Famous Five as feminist nation-builders was marked by much high-level political participation, with then Prime Minister Jean Chretien, Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Beverley McLachlin presiding. Many female members of parliament and senators who had actively supported the vote on the monument were there as well. The statue marked a major departure for women's commemoration in that it portrayed five women as real, named, and heroic figures in Canadian political history and generated a debate that is revealing of antagonism, even within the feminist community, toward according public space to feminist heroines. Critics argued that the Persons Case was unimportant because women already had the vote, could hold office in the House of Commons and provincial legislatures, and that the Senate was non-elected, elitist, and irrelevant. The F5F countered that the Persons Case "was an important legal, constitutional achievement because it allowed Canadian women to serve as senators, thereby finalizing our laws . . . As well, the decision by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council affected all British empire countries."(98)

Forced to address well-established criteria in place for the Parliamentary precinct that singled out the Fathers of Confederation, the foundation argued that the Famous Five should be considered "Mothers of Confederation." They argued that the five women had contributed as much or perhaps more to the country than many of the "fathers." Critics within the feminist community who questioned "the historical desserts of a small group of Anglo-Celtic foremothers,"(99) painted the five women as both elitist and racist, because they supported popular eugenics beliefs of the early 20th century. This led one commentator to wonder whether women "as historic actors and subjects of monuments" are "being held to higher standards today than were the men whose statues dominate the historic landscape?"(100)

Women's History and National Historic Sites

Returning to the HSMBC/Parks Canada program, we look at the few women's history sites designated within the program. Dolores Hayden has observed that the exacting criteria in place in many heritage programs make it difficult to identify, develop, and interpret women's history sites.(101) Marginalized politically and economically, with loyalties divided across ethnic, class, and other identities, and spread out over diffuse geographic space, women have rarely designed, built, or had longstanding association with prominent public buildings, cultural landscapes, or major institutions, with the possible exception of Catholic women's communities. This section looks at the HSMBC/Parks Canada experience in relation to women's site designations. As of 2008, there were, as noted earlier, 1,942 designations and of that number 935 are sites, compared with 612 persons and 395 events. The 126 designations that relate to women show an opposite trend: only 27 are sites while 66 are persons, and 33 are events. As of 2008, there were 159 national historic sites administered by Parks Canada out of the 935 sites, and of these there is not one fully dedicated to a women's history theme.

Through most of the HSMBC/Parks Canada's history, Canadian women have had difficulty accessing the needed material and human resources to acquire, develop, and interpret sites, and to gain site designations once they have developed them. Before 1990, there were only nine women's history sites and most of those belonged to religious communities. However, since the late 1990s when Parks Canada made women's history a program priority, the number of sites, albeit not administered by Parks Canada, has increased substantially as the agency acquired sites that women's groups or local organizations had earlier developed.

In some respects the Canadian experience, taking into account the much smaller population, compares with that of the United States where approximately 50 women's history sites (not all of these U.S. National Park Service sites) have public programming. With the exception of the religious communities' architecture in Canada, they reflect similar themes, commemorating noted writers (Louisa May Alcott), prominent political wives (Mamie D. Eisenhower), and founders of organizations (Clara Barton, American Red Cross). However, Canada does not have a site devoted to political emancipation similar to the U.S. National Park Service's Women's Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, which includes the site of the 1848 founding meeting as well as former homes of movement leaders, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Mary Ann McClintock.(102) As we will see in the following section, none of the major leaders of the Canadian women's movement have been the focus of national historic sites in any of their former homes.

Literary Women and Politicians

The efforts of women's groups and others to celebrate women's history were met with relative indifference by the board in its early years, particularly when they nominated subjects who played controversial political roles. Women who excited the popular and/or board imagination from the 1930s to the present were elite writers or artists who enjoyed a national and especially international following, thus inspiring recognition for Canada. For example, after deferring on a proposal in 1958 and 1959, the board recommended designation of the Emily Carr House, in Victoria, B.C. in 1964, for its age, architecture, and association with the noted West Coast artist.(103) While the Emily Carr Foundation purchased the building, Parks paid a total of $25,000 towards the cost of acquisition and restoration.(104) The text reads—

Artist and author Emily Carr was born here and lived most of her life in this neighbourhood of Victoria where she died. Her compelling canvases of the British Columbia landscape offer a unique vision of the forest and shore, while her documentation of Indian villages provides a valuable anthropological record. Lively accounts of Emily Carr's travels in the province are collected in Klee Wyck, for which she won the Governor General's Award for non-fiction in 1941. Six other autobiographical works are memorable accounts of her world.(105) |

Chiefswood was not as readily accepted. It was the home of poet Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake, (1861-1913); her father, Mohawk Chief George Henry Martin Johnson, and her British born mother, Emily Johnson. When presented with a request for designation in 1923, the HSMBC deferred a decision, and in 1929 it declined a proposal to make the site a national park. A year later a nomination of Pauline Johnson herself was deferred to a sub-committee headed by HSMBC chairman and military historian, Brigadier General E. A. Cruickshank. It appears from the next mention of Pauline Johnson in the minutes that she was designated in 1945 and Chiefswood was recommended for national historic site status in 1953. At that time the board recommended erecting a secondary tablet, and pronounced itself in opposition to providing funds for Chiefswood's restoration.(106) Although her famous poem "The Song My Paddle Sings" extolling the British connection was learned by countless schoolchildren, Johnson also, "self-consciously drew on her part-Mohawk heritage to create a public image that fostered her role as a spokesperson for Native concerns" as well as speaking for Aboriginal women.(107) During the early years of the board, when historiography was dominated by imperialism and there was general indifference to Aboriginal and women's history, Johnson did not fit the model of an artistic figure that enhanced pride in Canadian identity. As sometimes happened, the board de-designated Johnson in 1961, declaring that Chiefswood did not deserve to be preserved because it was the birthplace of Pauline Johnson.(108) A later board changed its mind and Johnson was again designated in 1983. The records do not allow us to say why with any certainty, but it was likely due to heightened community and academic interest. Her text was approved in 1985—

Born here at Chiefswood, the daughter of a Mohawk chief, E. Pauline Johnson gained international fame for her romantic writings on Indian themes, but she also wrote about nature, religion and Canadian nationalism. Beginning in the 1890s, she published numerous poems, essays and short stories and recited them in theatrical fashion on public stages throughout Canada and abroad. Reaching a wide audience, she succeeded in making the public more aware of the colourful history and cultural diversity of Canadian Indians. Her ashes were buried in Stanley Park, Vancouver.(109) |

There was much less ambivalence toward Anglo-Celtic Lucy Maud Montgomery (1874-1942), famed Canadian author of Anne of Green Gables, potent symbol of Canadian identity, and a jewel of Prince Edward Island tourism. She was designated as a person in the 1940s and in November 1994, the board considered Leaskdale, Montgomery's home as an adult, as a historic site. (Figure 2) Although they opted to wait for a paper providing guidelines on sites associated with persons of national historic significance, the board said yes in 1996 and agreed that the program should enter into talks toward the goal of future funding assistance—

Internationally renowned author, Lucy Maud Montgomery was born in New London, Prince Edward Island. After her mother's death in 1876, she lived with her maternal grandparents in Cavendish until 1911, when she married and moved to Ontario. While residing in Cavendish she wrote her first novel, Anne of Green Gables (1908). A series of popular sequels and other successful novels followed, but the enduring fame of Lucy Maud Montgomery had been firmly established with her creation of Anne, one of the most lovable children in English fiction. She died in Toronto and is buried at Cavendish.(110) |

Montgomery remains popular. In 2003 the board recommended designation of the L.M. Montgomery Cultural Landscape in Cavendish, Prince Edward Island, as a site associated with Montgomery's formative years.(111)

The board did not respond as favorably to most female politicians. The board added Agnes Macphail (1890-1954) to its list of distinguished Canadians in 1955. She was a former teacher who became the first woman elected to the House of Commons following the enfranchisement of women in Canada. However the designation was revoked in 1973 in a backlog clearance exercise. When Macphail's house in Ceylon, Ontario came up before the board in November of 1976 it decided that it was not of national historic or architectural significance and a year later the HSMBC declared that Macphail herself was not of historic significance. However, in 1985 when Macphail was studied in the context of a study on the cooperative movement, she received a positive recommendation.(112)

Still, a plaque inscription for Macphail was not written and approved until February 1990. After revising it in 2005, Parks Canada has scheduled placement of the plaque at the Ceylon home for October 2010—

Agnes Macphail was the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons following the enfranchisement of women in Canada. A rural schoolteacher, she joined the United Farmers of Ontario, and ran successfully as a Progressive candidate in the 1921 federal election for Grey County. In Ottawa she fought for penal reform, disarmament, and social welfare, and championed the cause of the disadvantaged. Defeated in 1940, she sat as a CCF member of the Ontario legislature from 1943 to 1951. Witty and forceful, fearless and uncompromising, Macphail left a lasting mark on Canadian public life.(113) |

The records do not tell us why Macphail was so neglected at the federal level. In a program driven by public interest, she may not have had as strong a proponent as did Nellie McClung or the religious women. Macphail was associated with the cooperative movement, the United Farmers of Ontario, the Progressive Party and later the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, but like many early female politicians, she resisted party affiliation. Recognized as the first woman Member of Parliament, she did not seem to identify with the women's movement. As she explained—

Even after twenty-five years ...I still recall clearly ... each time I left my own community I was appalled by the publicity — both the quantity and the inaccuracy of it. It seemed that not one reporter could put down exactly the simple facts of my life. It was too simple; that was the trouble. A young woman from a farm with faith in the tillers of the soil and devotion to them, who knew nothing of cities and their ways had no business being elected the first woman M.P. What did she know of the Women's Clubs, of fashion, of society? Nothing, nothing.(114) |

Perhaps Macphail doesn't have the same appeal as other elite women who had been recognized. She was not a colorful "character" in her community despite her long tenure as their political representative. She was not a pioneer and except for a brief stint as a teacher, did not engage in traditional feminine activities. As seen from the mainstream political elite she disrupted the all-male preserve of Parliament, supported leftist causes and was "uncompromising." Not having cultivated the patronage of the women's community, the latter didn't push for her recognition at the national level.

The records do not tell us, but perhaps the original proponent(s) of her house in Ceylon gave up and decided to be satisfied with designation at another level of government. In recent years, it seems that new proponents have emerged and done just that. In June 2006, they placed a stone cairn with a plaque at her birth site to celebrate the 85th anniversary of Macphail's election to the House of Commons.(115) The local plaque text reads:

Agnes Macphail Cairn Plaque Agnes Macphail |

Another non-HSMBC plaque was placed at her home in Ceylon, where she lived later in her life, as part of the National Action Committee (on the Status of Women's) Women's Voting Day celebrations.(117)

Proponents for Nellie McClung, suffragist, author, early provincial female politician, and member of the Famous Five, were offered a plaque for a person designation in lieu of a historic site. Two of her former homes have come before the board and been rejected. A house in Manitou, Manitoba, associated with the early part of her career, was nominated as a national historic site in 1958. The question was referred to Manitoba member, Father d'Eschambault who felt that "the Federal Government would not be interested in taking over this house as it seems to have been only the house of a writer." He reminded the board that the work of Nellie McClung had been commemorated with a plaque at her birthplace at Chatsworth, Ontario.(118) Although Dominion Archivist William Kaye Lamb remarked that McClung "had caught a certain stage of development of tremendous value which will be recognized some day," the board did not act. Referring the matter to provincial attention, d'Eschambault suggested that the Manitoba Heritage Council might consider the proposal for the preservation of this home.(119) A Calgary, Alberta house associated with McClung's post-suffrage period and career as a provincial politician, was also nominated and turned down in 1976, because it was "not of national historic or architectural significance."(120)

Another female politician and colorful pioneer, Martha Louise Black (1866-1957), was designated in 1987 but only after a lengthy discussion in which the board debated the possible national significance of her husband, George Black, a Conservative MP representing the Yukon.(121) They concluded in 1991: "while he is of some interest, George Black, the last Commissioner of the Yukon, is not of national historic significance."(122) Martha Black became the second women elected to the federal Parliament when her husband became ill and she ran in his riding, holding the seat from 1935-40. Black seemed to have had greater commemorative appeal than Macphail, as reflected in her plaque text—

A legendary figure among northerners who admired her pioneering spirit, Chicago-born Martha Munger Purdy climbed the Chilkoot Trail in 1898 to join the Klondike gold rush. Later, she operated a sawmill near Dawson, and in 1904 married George Black, who served as Commissioner of the Yukon. Awarded the Order of the British Empire for volunteer work in Britain during the First World War, she was also made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society for her research on Yukon flora. She became Canada's second female M.P. when she replaced her ailing husband for one term (1935- 1940).(123) |

Like Verchères who defended the fort, Black had shown spunk and determination in taking on pioneering roles usually performed by men. Similar to another recognized pioneer Catherine Parr Traill, Black was also an amateur botanist. Unlike Macphail who made a career in politics, Black cheerfully told her admirers that she had only been holding her husband's seat during his illness. While admired for her spirit, she perhaps ruffled fewer feathers than the career politician and first female Member of Parliament had.

The Women's Institutes

The Canadian experience with Women's Institutes reflects a similar trend in the United States where house museums have been developed by such organizations as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and the Girls Scouts of America in dedication to their respective founders.(124) In Canada, only a few very determined grassroots women's organizations were able to create women's history sites, usually devoted to remembering a founder, although they had to do so through their own initiatives and fundraising. The Women's Institutes are a network of rural women's organizations founded in 1897 with government funding in the hopes they might help stem the tide of rural depopulation. The mandate of the organization was to educate farmwomen on agricultural and domestic skills. It also contributed to community building, including collecting local histories and providing support to heritage organizations such as the HSMBC.(125) When the Women's Institutes wanted to preserve their own historic sites, however, the board provided them with little support. In 1937 the HSMBC, at the request of the Women's Institutes, recognized the formation of the First Women's Institute at Stoney Creek, Ontario as a nationally important event, to be commemorated by the erection of a memorial bearing an inscription—

Commemorating the formation at Stoney Creek, on 19th February 1897, of the first Women's Institute in Canada, initiating a movement of inestimable value for the betterment of rural life, which has spread throughout the British Commonwealth of Nations and the United States of America.(126) |

Commemoration was delayed by World War II and then in 1956 the minister refused to allocate funds for the plaque because "he feels that the national importance of the subject is not perfectly clear, and that there are still many sites clearly of national importance that should be considered or marked before he can give consideration to this tablet."(127) Although, there was likely some confusion between the Stoney Creek site and the Hoodless Homestead, both associated with the founding of the Women's Institutes, the lack of priority given to women's history is also clear.(128)

The Federated Women's Institutes of Canada (FWIC) approached the HSMBC in 1959 with a request for financial assistance to create a historic site celebrating its founder. While the HSMBC asserted that the Women's Institutes were "of very great importance" it did not recommend negotiations by the department for the purchase of the birthplace of Adelaide Hoodless. Instead, board members reaffirmed their earlier recommendation that a tablet be erected at Stoney Creek. Expressing some ambivalence, board member and historian Dr. Arthur R.M. Lower described the Women's Institutes as an "extremely powerful body" while Chair Donald Creighton suggested that such "a large national body should be able to accomplish the purchase of the birthplace of its foundress."(129) As well, the board, at its next meeting, expressed reservations as to whether the Women's Institutes, a movement in the abstract sense, could be commemorated, wondering if the HSMBC mandate only allowed them to commemorate sites and persons.(130) But the women tried again. In 1960, the board minutes recount: "received a delegation from the Federated Women's Institutes of Canada who spoke about their organization's hope that the Federal Government would help their efforts to restore and maintain the Adelaide Hunter Hoodless Birthplace." With no money to offer, the board moved and carried that "in the opinion of the Board Mrs. Hoodless should be classified as an eminent Canadian" and that steps be taken to erect a secondary plaque honoring Hoodless at her birthplace.(131) The federal plaque first proposed in the 1930s did not go up at Stoney Creek until recently, when this designation was merged with a site designation of the Erland Lee home. (Figure 3)

|

Figure 3. Erland Lee (Museum) Home, Stoney, Creek, Ontario, Parks Canada. |

Initially, the Federated Women's Institutes of Ontario (FWIO) was no more successful in its efforts to partner with the board and Parks Canada in creating a national historic site out of the Erland Lee Home. In 1966, it approached both the HSMBC and Ontario Archaeological and Historic Sites Board (the provincial heritage body) with a proposal to have what was then called the Lee Homestead designated a a national historic site. It anticipated "that the organization will raise one third of the purchase price, and would hope that the federal and provincial governments between them would contribute the balance."(132) The HSMBC declined the request because "there had been adequate commemoration of the Women's Institutes."(133) The following year, however, the provincial board put up a plaque in front of the home. While the Ontario government assisted in the purchase by offering legal services to the FWIO, no other government support, federal or provincial, was provided. The FWIO purchased the property in 1972 by raising $40,000 primarily through a 10-cent levy on each member.(134) It then proceeded to make restorations and develop an interpretive program.

New Women's History Sites

While earlier initiatives had failed, after women's history became a priority in the 1990s, efforts to commemorate women began to bear fruit. After spending its own money purchasing, restoring and running their two sites for several decades, the Women's Institutes saw its work become part of the national historic sites network. In 1995 the Hoodless Homestead was designated, the board noting—

Its concrete linkages with the contributions of Adelaide Hunter Hoodless, a champion of maternal feminism, who was instrumental in the founding of the Women's Institute, the Young Women's Christian Association, the National Council of Women, the Victorian Order of Nurses, and three faculties of Household Science. Further, the rural situation and lack of amenities found in the Hoodless' childhood home speak eloquently to the hard labour and isolation experienced by many rural women in the mid 19th-century, a situation that Hoodless spent her entire life trying to alleviate.(135) |

Similarly, in 2000, on learning that Parks Canada had made women's history a strategic priority, the curator of the Erland Lee Home, with backing of the Women's Institutes, nominated it as a site of national significance. It has now been designated. After initially refusing financial support to Chiefswood, home of Aboriginal poet Pauline Johnson, Parks Canada entered into a partnership in 1997 with the Six Nations Council to enhance interpretation there.(136) Early sites such as the Grey Nuns Convent and Hôtel-Dieu which were designated for other reasons, are now being linked with other women's history designations and interpretation is being enhanced both at the actual sites and in products created for the Parks Canada website.(137) In some cases, we see a different emphasis in interpretation as Parks Canada stressed the leadership role of the nuns in establishing the French Catholic Hospital system in British and French North America, and their competent administration of this and other hospitals for over three centuries. By contrast the locally run museums may place greater emphasis on the religious aspects of the community and their role in its founding. As well, Parks Canada historians continue to work quietly away at bringing the voices of women to bear on established interpretation at sites such as the Fortress of Louisbourg, the Quebec Arsenal, and at Batoche.(138)

Recent additions to the group of historic sites relating to women's historic achievements include five nurses' residences, commemorated as places where both rank-and-file nurses and their leaders forged a new profession for women.(139) The Ann Baillie Building, which houses the Museum of Health Care at Kingston, recently launched a new permanent exhibit on nursing education. As well, two outpost nursing stations, Wilberforce Red Cross Outpost Hospital and La Corne Dispensaire, were designated as sites representative of the pioneer outpost nurses who bravely faced life in isolated communities, and cared for the sick and injured as well as childbearing women and their babies with minimal medical support. Like the two sites associated with the Women's Institutes, both were developed through community initiative.(140)

Recent Trends

Besides the underrepresentation of ethnic and gender perspectives, which the federal commemorative program is now beginning to address, the program is also weak in conveying stories that address class.(141) To date, only two designations directly address women in the labor movement.(142) Neither have there been many designations of Aboriginal and ethnocultural women. Aboriginal commemorations tend to focus on women with ties to white elites, sometimes through their husbands, and are thus better documented in the written record. For example, the Inuit couple, Taqulittuq and her husband Ipirvik, were commemorated for assisting an American group of explorers in surviving their 1872-73 Arctic expedition.(143) More recently, Thanadelthur, an Aboriginal woman who played an important role in the English fur trade in the Canadian North in the early 18th century has been recognized as a person of national significance. In the ethnocultural field, African Canadian singer Portia White from Nova Scotia, Mary Ann Shadd, and Mary and Henry Bibb, African Canadian newspaper editors, educators and leaders in the black fugitive movement have been recognized. While a great deal more remains to be done, consultations now being conducted have led to some interesting new directions that incorporate ethnocultural and Aboriginal women. For example, a midwife in Vancouver's early Chinatown, Nellie Yip Quong, was nominated at a Vancouver workshop. This as well as another nomination from Québec on the "Midwives of New France" will add a much needed ethnocultural perspective to the commemorative program. As well, it helps the program move away from elite women 'worthies' working in the public sphere to exploring some of women's traditional knowledge and domestic practices.

Conclusion

This overview of 126 designations in a federal commemorative program raises as many questions as it answers. The program could serve as a starting point for researchers to conduct comparative studies on how women fared before the board in relation to other groups, notably men; explore Aboriginal groups, workers, and ethnocultural communities; and/or compare federal, provincial, and municipal level commemorations. The study offers a glimpse into the role of female heritage activists such as Harriette Taber Richardson and Katharine McLennan—there are no doubt many others associated with these designations who warrant further investigation.

Nonetheless we can draw a few conclusions. Women's commemorations at the federal level have been, and remain, underrepresented in terms of numbers and resources devoted to remembering the past. Yet the number of designations, particularly of sites, increased with "strategic priority status," thanks to the earlier efforts of female heritage activists, religious congregations, and local groups, many of them mainstream and/or conservative women's organizations, who brought women's history themes into the Parks Canada network of national historic sites. Women's history commemorations, mediated through the HSMBC, tell us that in the past elite Euro-Canadian literary and artistic women were more likely to become the subject of commemorative efforts than women who challenged patriarchal, class, ethnic, and social norms. Although person designations are still the most numerous, the increasing number of "event" designations in recent years suggests a reluctance to celebrate feminine heroes—a preference for collective recognition. Despite this, trailblazers in a number of fields—nuns, military women, nurses, founders of mainstream women's organizations, athletes, pioneers and feminists were relatively successful at fitting into the national criteria. Most women's contributions were presented in a way that was ambiguous enough to appeal to both feminists celebrating their foremothers, and conservatives who stressed women's traditional work in social welfare, health and education—women who displayed spunky if appropriately feminine devotion to community.

Discrepancies between commemorative themes and academic history may simply reflect the lag time in commemorative programs "catching up" with the historiography. Certainly many of the elite women founders reflect the early historiography on women. However, they also remind us that commemoration and academic research serve very different purposes. Agnes Macphail, whose career as a female politician has deservedly drawn much academic attention received only lukewarm commemoration at the federal level, especially in contrast to the colorful pioneer wife and botanist Martha Black who deferred to perceived gender roles by keeping her husband's seat in Parliament warm for him.(144)