Last updated: June 14, 2024

Article

NPS Geodiversity Atlas—Capitol Reef National Park, Utah

Geodiversity refers to the full variety of natural geologic (rocks, minerals, sediments, fossils, landforms, and physical processes) and soil resources and processes that occur in the park. A product of the Geologic Resources Inventory, the NPS Geodiversity Atlas delivers information in support of education, Geoconservation, and integrated management of living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components of the ecosystem.

Geologic Features and Processes

Capitol Reef National Park has some of the most spectacular geology in the western United States. Because of the brilliantly colored canyon walls, the Navajo people called it the Land of the Sleeping Rainbow. Examples of the natural beauty of this desert landscape include: the rugged spine of the Waterpocket Fold, high-walled gorges cut through the fold, monoliths, ridges, buttes, and miles of colorful canyons.

The Waterpocket Fold is one of the longest continuously exposed monoclines in the world and is the centerpiece geologic structure of Capitol Reef (Morris et al. 2000). The Waterpocket Fold monocline stretches for almost 161 km (100 mi), from the Colorado River south of the Henry Mountains, along the east side of the Circle Cliffs, northward to the north end of Thousand Lake Mountain. The general trend of the Waterpocket Fold is northwest-southeast. Between Oak Creek and the Fremont River, the fold trends approximately N 25º W, but north of the Fremont River the fold trends more westward to N 50º W.

The rock layers on the western limb of the fold are more than 2,100 m (7,000 ft) higher than the rock layers on the east. From the crest of the fold, the High Plateaus Section of the Colorado Plateau extends westward. To the east lies the desolate beauty of the Canyon Lands Section. Water is a powerful erosive agent, especially in a desert environment with scarce vegetation. Over time, water has carved catchments for surface runoff in the uplifted and tilted sandstone layers of the Waterpocket Fold. These small basins, also known as water pockets, are common throughout the fold and give this feature its name.

Folds and Faults

Capitol Reef National Park is geologically defined by the escarpment of the Waterpocket Fold, a nearly 160-km long (100-mi) step-like flexure (monocline) in the sedimentary rock. Associated large-scale geologic structures include anticlinal and monoclinal folds, faults, and fractures. Other prominent structural features of the Capitol Reef region are the Teasdale Anticline, the Teasdale Fault, and the Thousand Lake Fault, discussed in Geologic Features and Processes below. Most of the major faults lie west of the Waterpocket Fold (Smith et al. 1963; Billingsley et al. 1987). On the surface, the majority of the faults have been mapped as normal faults that follow the northwest-southeast trend of the anticlines and synclines (Billingsley et al. 1987). While some normal faults are thought to have fractured rocks from the surface down through the Precambrian, most are interpreted as relatively shallow (Billingsley et al. 1987). However, interpretations of the faults at depth may be suspect because of limited subsurface geologic data.

Reverse faults in the subsurface have been mapped as dipping 60º to the southwest (Billingsley et al. 1987). Billingsley and others (1987) mapped the reverse faults below Capitol Reef as blind thrust faults that disturb Precambrian through Mississippian rocks. Blind faults are buried faults that have no surface expression. Younger strata have been folded over the axis of the reverse faults beneath Capitol Reef but have not been offset, or fractured, by the underlying faults.

While the Waterpocket Fold is the dominant geologic feature of Capitol Reef National Park, the park also contains classic elongated “strike” valleys, dikes and sills, intrusive gypsum domes, massive landslides, fossilized oyster reefs, petrified logs, dinosaur bones, bentonitic hills, and unusual soft-sediment deformational features. Geologic features include:

-

Teasdale Anticline

-

Teasdale Fault

-

Thousand Lake Fault

-

Vertical Joints

-

Dikes and Sills

-

Ice Age Deposits and Landforms

-

Cathedrals and Monoliths of Cathedral Valley

-

Glass Mountain and Gypsum Sinkhole

-

Bentonite Hills

-

“The Goosenecks” at Sulfur Creek

-

Arches and Bridges

-

Capitol Dome and Navajo Dome

-

Cavernous Weathering

-

Slot Canyons

-

Soft-Sediment Deformation

-

Unconformities

-

Oyster Reef

-

Strike Valleys

Also see the park Geologic Resources Inventory Report for more information on these features.

Rocks at Capitol Reef National Park range in age from Permian to Tertiary and record 275 million years of the earth’s history. The strata represent a variety of ancient environments including open marine, nearshore, fluvial (river), lacustrine (lake), and desert. The highest point in the Capitol Reef area is Blue Bell Knoll, a low, rounded hill on top of Boulder Mountain at 3,446 m (11,306 ft) in elevation. The irregular outline of Boulder Mountain has been deeply cut by several broad glaciated valleys. Thousand Lake Mountain is a smaller flat-topped feature located north of Boulder Mountain.

Paleontological Resources

Paleontological resources are abundant in Capitol Reef. Marine invertebrate fossils are found in Permian strata and thick accumulations of Cretaceous oysters form the Oyster Reef exposed along the Notom-Bullfrog Road. Ancient marine and terrestrial vertebrates such as turtles, crocodiles, and dinosaurs are also preserved in Capitol Reef. Reptile and amphibian tracks are present in the Triassic Moenkopi Formation.

The Permian White Rim Sandstone (Cutler Group) crops out locally within the park and contains marine trace fossils of Thalassinoides and Chondrites. The fossiliferous Kaibab Limestone interfingers with the White Rim Sandstone and contains fragments of marine invertebrates such as bryozoans, brachiopods, gastropods, bivalves, and crinoids (Koch and Santucci 2002).

Brachiopods, gastropods, bivalves, and ammonites are found in the Sinbad Limestone Member of the Triassic Moenkopi Formation. The Moenkopi also contains fossil vertebrate tracks of Rotodactylus and swimming traces of Chirotherium (Mickelson 2004). Invertebrate fossil traces of Palaeophycus, and Diplidnites are reported from the Torrey Member of the Moenkopi Formation (Santucci et al. 1998).

The Shinarump Member of the Triassic Chinle Formation contains abundant paleobotanical fossils such as Zamites powelli, Palissya sp., Sphenozamites sp., abundant stems of the fossil horsetails, Equisetites, Phlebopteris, Cyneopteris, Cladophlebis, Pagiophyllum, and Araucarioxylon (Koch and Santucci 2002). Leaves of the palm-like plant Sanmiguelia cf. S lewisi have been found in the Owl Rock Member of the Chinle Formation. Other fossils from the Chinle include tetrapod remains, lungfish toothplates and burrows, coprolites, marine snails, and bivalves.

Dinosaur and tritylodont tracks are reported from the Lower Jurassic Kayenta Formation (Santucci et al. 1998). The Lower Jurassic Navajo Sandstone, primarily an eolian deposit, also contains algal mounds formed in interdunal playa deposits in Capitol Reef NP (Koch and Santucci 2002).

All NPS fossil resources are protected under the Paleontological Resources Preservation Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-11, Title VI, Subtitle D; 16 U.S.C. §§ 470aaa - 470aaa-11).

Abandoned Mineral Lands

Capitol Reef National Park has been closed to mineral entry including oil and gas since it was established as a National Monument in 1937, with the exception of a period from 1953 to 1955 when uranium exploration was allowed (Smith et al. 1963). Mineral occurrences in the area include uranium, vanadium, copper, manganese, gypsum, minor coal, building stone, sand and gravel, and oil and gas (Smith et al. 1963; Doelling and Tooker 1983).

Uranium

The presence of uranium in the Capitol Reef area has been known for many years and the presence of ten abandoned mineral land sites related to uranium mining attest to development of these uranium deposits. The monument was again closed to mineral entry after May 1955. The Oyler mine, established on the north side of Grand Wash in Capitol Reef, was located in 1901 and is the oldest uranium-radium prospect in the Capitol Reef area.

Waste rock piles in the park are somewhat stabilized by caliche on their surface, however a potential radiation hazard exists and visitors are advised not to camp out on the piles or drink water from the area.

NPS AML sites can be important cultural resources and habitat, but many pose risks to park visitors and wildlife, and degrade water quality, park landscapes, and physical and biological resources. Be safe near AML sites—Stay Out and Stay Alive!

Geohazards

Natural geologic processes continue to shape the park on time scales ranging from seconds to years. Natural materials and processes can create geologic hazards and associated risks. Be cautious and alert to geohazards that may be present in the park, including:

-

Flash Flooding and Debris Flows

-

Swelling Clays

-

Uranium and Radon Contamination

-

Rockfall and Landslides

-

Seismic Activity

Also see the park Geologic Resources Inventory Report for more information on geohazards.

Regional Geology

Capitol Reef is a part of the Colorado Plateaus Physiographic Province and shares its geologic history and some characteristic geologic formations with a region that extends well beyond park boundaries.

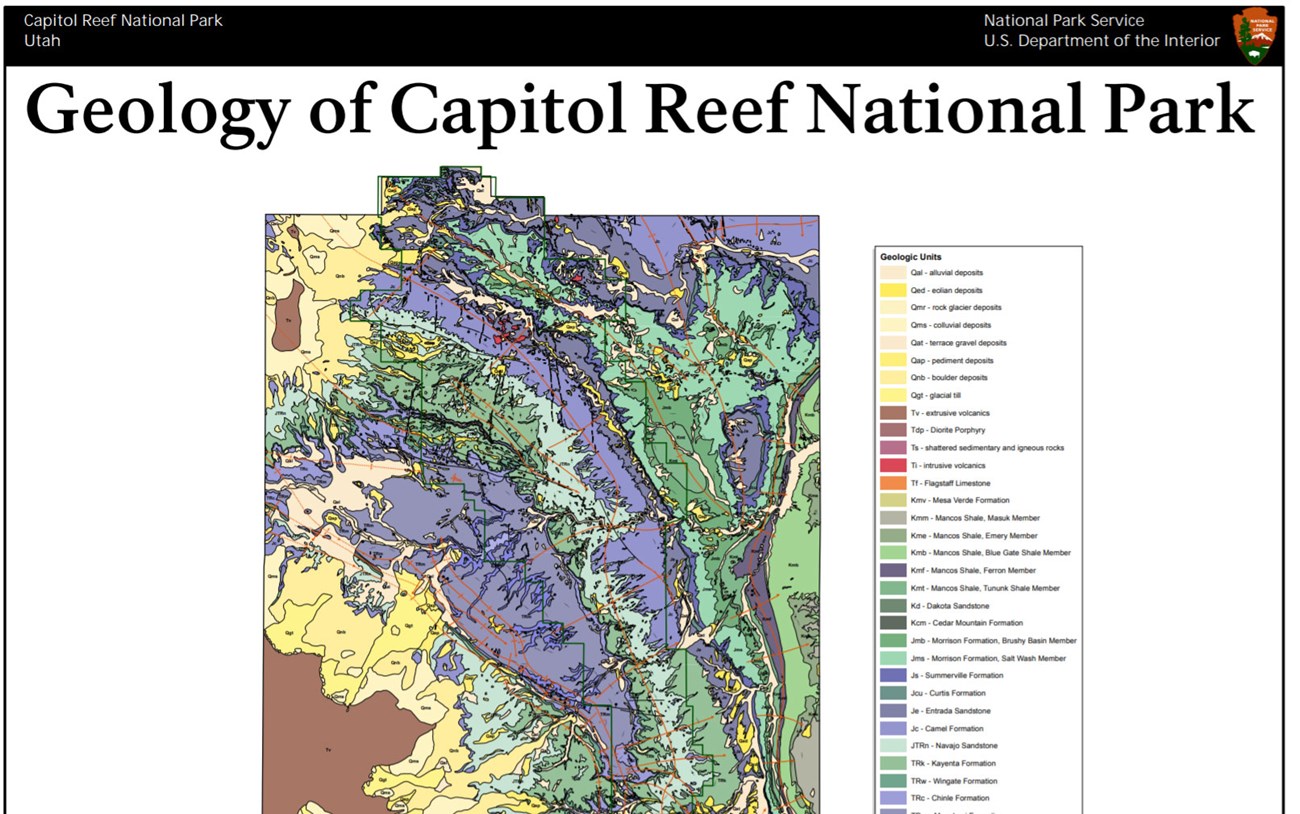

- Scoping summaries are records of scoping meetings where NPS staff and local geologists determined the park’s geologic mapping plan and what content should be included in the report.

- Digital geologic maps include files for viewing in GIS software, a guide to using the data, and a document with ancillary map information. Newer products also include data viewable in Google Earth and online map services.

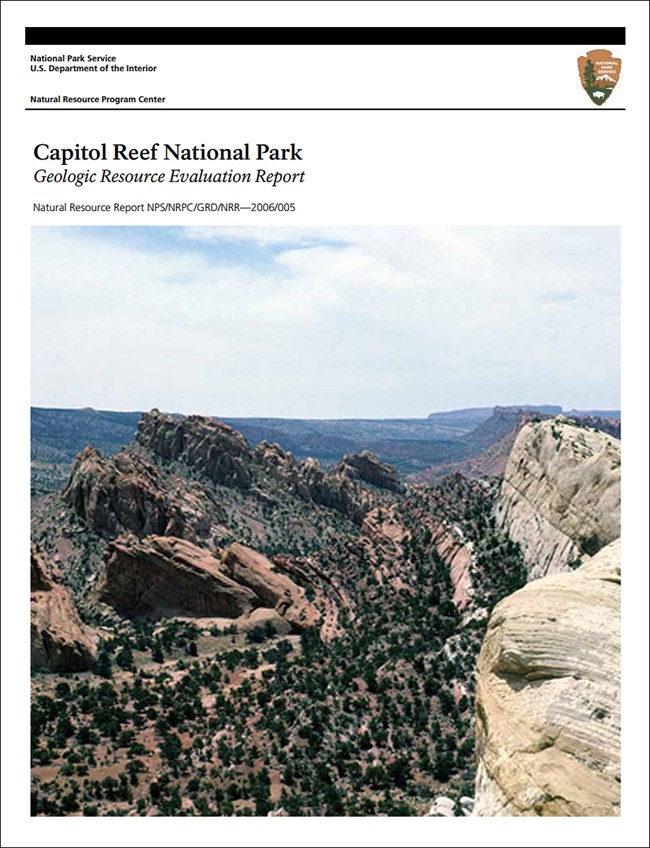

- Reports use the maps to discuss the park’s setting and significance, notable geologic features and processes, geologic resource management issues, and geologic history.

- Posters are a static view of the GIS data in PDF format. Newer posters include aerial imagery or shaded relief and other park information. They are also included with the reports.

- Projects list basic information about the program and all products available for a park.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2766. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

A NPS Soil Resources Inventory project has been completed for Capitol Reef National Park and can be found on the NPS Data Store.

Source: NPS DataStore Saved Search 2748. To search for additional information, visit the NPS DataStore.

Related Links