Last updated: May 5, 2022

Article

Green Book Properties Listed in the National Register of Historic Places

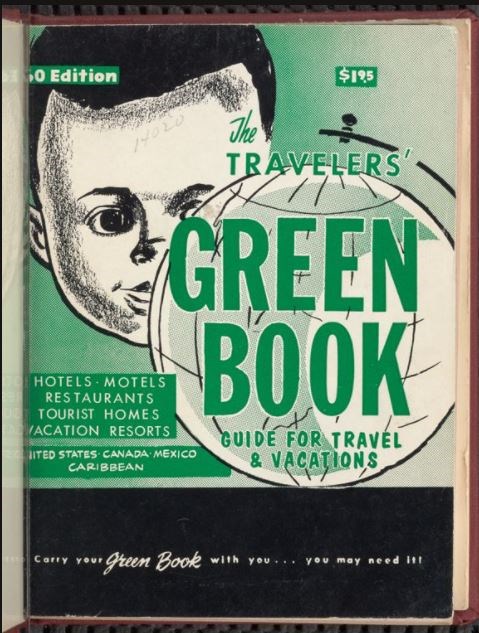

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. "The Travelers' Green Book: 1960" New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections nypl.org

Following World War I, Green returned to working as a postal carrier. After years of frustrating travel experiences during his routes in segregated areas and among intolerant people, Green came up with the idea of publishing a travel guidebook for African American civilians. The Negro Motorist Green Book was the product. Green originally cultivated the idea in 1932, when he encountered constant complaints from friends and neighbors about difficult and uncomfortable experiences they had while traveling by automobile. Green modeled the guide after those created for Jewish travelers, a group that had also experienced discrimination. The first edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book was produced in 1936 and was initially limited to listings in New York City. Within the first few months of being published the demand for the guide was so high that the following year it became national in both scope and distribution.

The context of the Greenbook was a directory of safe places for African American travelers to use as they enjoyed the liberties of automobiles and the roads that connected families and experiences. The directory included black owned businesses and tolerant white owned businesses that did not discriminate against Black customers. Businesses like hotels, motels, restaurants, beauty and barber shops, service stations, garages, nightclubs, resorts, and beaches were among the many types of spaces that the book offered. The most high-volume listings were in cities with large populations of Black Americans, like New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles. But the book’s use was more valuable to travelers crossing smaller towns in rural areas across the South and out West.

Green compiled the listings through his connections in the postal workers’ union, as well as by asking Green Book users to submit information on sites in their areas. As the book became more popular, Green commissioned agents to solicit new business listings as well as to verify the accuracy of existing sites. Green distributed the books by mail order, to black-owned businesses, and at Esso Standard Oil service stations. Esso was a rare gasoline distributor that franchised to African Americans. Copies of the book were sold at Black churches across the country, the Negro Urban League, and almost anywhere that African Americans were bound to encounter them in their city or along the highways.

Publication of The Green Book was briefly suspended between 1942 and 1946, due to the war efforts during World War II. However, shortly after the return of many African American soldiers, the need for the book picked back up in the wake of the postwar travel boom in 1947. While the book was initially used as navigational aid through the Jim Crow era, as time went on the book expanded its listings to recreational spaces and vacation destinations. In 1952, Green retired from the postal service and became a full-time publisher. In the guide, Green often produced editorial commentary in the guide on the social and civil issues of American society and the challenges of segregation. Green was optimistic that the guide would no longer exists as the nation progressed towards an integrated union. As time and technology progressed, Green renamed the guidebook “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book” to reflect the increasing popularity of international travel by ship and airplane. By 1955, the book was endorsed and in use by the American Automobile Association and its hundreds of affiliated clubs throughout the country, as well as travel bureaus, bus lines, airlines, travelers’ aid societies, and libraries.

The demand for The Green Book began to decrease after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, that legally prohibited racial segregation, passed. The Green Book continued until 1966, published by Victor Green’s family after his death in 1960. Until the last year of publication, the book maintained that listing black-friendly businesses guaranteed hassle-free vacations for African American families. For 30 years, The Green Book protected and guided African American travelers across the country. The book is a tangible resource that highlights the entrepreneurial success of Black owned and women owned businesses in the Jim Crow era of our nation’s history.

Today, according to Architectural Historian Jennifer Reut, an expert participant with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, it is estimated that less than 20 percent of the sites listed in The Green Book are still extant. Fewer have been documented, maintained, or preserved. Communities and advocates across the country are working together to identify and collect the stories of the events and people that sustained the Green Book sites. Twenty individual listed properties in the National Register of Historic Places have been identified as being in the Green Book. To learn more about the identified sites check out the list below.

Photograph by Apama Surte, courtesy of Texas State Historic Preservation Office

Read More

Photograph by Andrew W. Chandler, courtesy of South Carolina Historic Preservation Office

The Harriet M. Cornwell Tourist Home in Columbia, South Carolina, is a surviving example of an alternative space created by an African American family that provided other African American families a place to rest as they passed into town.

Read More

Photograph by Ralph S. Wilcox, courtesy of Arkansas Historic Preservation Office

The Latimore Tourist Home inn Russellville, Arkansas, operated from the 1940s until the 1970s, providing overnight accommodations to African American travelers passing through the Russellville area.

Read More

Photograph by Robert Frame III, courtesy of Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office

The Avalon Hotel was part of the early hotel building boom that grew out of the 20th century. The Avalon Hotel became the only hotel available in Rochester for Black patients at the clinic, a function it performed for several decades until the end of color barriers.

Read More

Photograph by Christi A. Mitchell, courtesy of Maine State Historic Preservation Office

The Cummings’ Guest House is an example of a beach town lodging that catered to African American tourists. The Cummings’ Guest House is one of several facilities in Maine that catered to African American tourists via a network that relied initially on word of mouth and personal references, and eventually propagated through specialized touring guides like The Negro Motorist Green-Book.

Read More

Photograph courtesy of South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office

Allen University was among the many private schools and universities for African Americans founded during the Reconstruction Era. Allen University was one of the first private black school founded and operated by Black faculty and scholars in South Carolina.

Read More

Photograph by Courtney Mooney, courtesy of Alabama Historic Preservation Office

Built by prominent African American businessman and entrepreneur, Arthur George Gaston, provided first-class lodging and dining in Birmingham, Alabama, to African American travelers. The A.G. Gaston Motel was also an important resource in the Birmingham Campaign to help end racial segregation in public accommodations in the city.

Read More

Photograph by Nancy Lyons, courtesy of Colorado State Historic Preservation Office

The Rossonian Hotel was one of the most important African American jazz clubs between St. Louis and Los Angeles from the late 1930’s to the early 1960’s. The Rossonian welcomed a mixed clientele of music lovers who enjoyed popular jazz by black and white musicians in the same venue.

Read More

Photograph by Anthony Robins, courtesy of New York Historic Preservation Office

The Hotel Theresa, was one of the major social centers of Harlem, serving from 1940 until its conversion into an office building in the late 1960s as one of the most important institutions for Harlem’s African American community.

Read More

Photograph by William Maclane Hull, courtesy of the South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office

Leevy’s Funeral Home was part of a community effort by the city’s Black citizens, to create alternative spaces to gather and provide one another with essential services such as voting registration, education, and funerary services.

Read More

Photograph by Carlie N. Todd, courtesy of South Carolina Historic Preservation Office

Ruth's Beauty Parlor in Columbia, South Carolina is significant for its association with Black beauty culture and entrepreneurship. Ruth’s Beauty Parlor opened in 1939 and remained in operation until at least 1943.

Read More

Photograph by Ramon Jackson and Holly Floyd, courtesy of South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office

The Ebony Guest House is a historically Black lodging establishment located in the North Florence neighborhood. Ebony Guest House is the only known extant property in Florence to have provided service as an African American tourist home.

Read More

Photograph by Courtney Mooney, courtesy of Nevada Historic Preservation Office

Harrison’s Guest House is significant for its use as an African American boarding house that provided housing to the wartime laborers as well as black entertainers performing at the nearby casinos and resorts. Today the house stands as the only known example of its type remaining in Las Vegas in the Green Book.

Read More

Photograph by Thomas H. Simmons, courtesy of Colorado State Historic Preservation Office

The Coronado is significant for its role in the local tourism and hospitality industry in Pueblo since 1946 with association to the history of African American travel and tourism during the era of segregation.

Read More

Photograph by Craig Leavitt, courtesy of Colorado State Historic Preservation Office

Winks Panorama is a historic African American resort in the Rocky Mountain West. The property was used between 1925- 1965 as a peaceful mountain oasis that offered African American vacationers’ leisure.

Read More

Photograph by Rory Krupp, courtesy of Ohio State Historic Preservation Office

The Manse Hotel and Annex is significant for African American social history in Cincinnati, Ohio. Due to segregation in public accommodations, the Manse Hotel and Annex became a destination for African American travelers visiting Cincinnati.

Read More

Photograph by Holly Barnett, courtesy of Tennessee State Historic Preservation Office

The Booker T. Motel was a safe haven for African American travelers to gather and socialize over a meal. The site was a significant contribution to the commercial history of the African American in Humboldt.

Read More

Photograph by Ajay Suresh, Harlem - Apollo Theater, cc-by-2.0

The Apollo Theater is historically and architecturally significant for its role as one of New York City's and the nation's leading entertainment centers for over four decades. Famously recognized as the premier performance hall for black American performers and a symbol of the movement to promote black cultural awareness in the 1930s.

Read More

Photo by Corinne Engelbert & Marcio Tavares, courtesy of New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office

The Liberty Hotel was constructed in 1928 and accommodated African American tourists in “Northside” neighborhood during the heyday of Atlantic City’s resort tourism.

Read More

Matthew T Rader, MatthewTRader.com, License CC-BY-SA

Located in the South Main Street Historic District, the Lorraine Motel became one of the few black owned establishments in Memphis and one of the only hotels that provided accommodations to African Americans. The Lorraine Motel is national recognized as the site of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968. The building is currently associated with The African American Civil Rights Network.

Read More

Photograph by Caitlin Cutrona, courtesy of South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office

Operating for over seventy years within Lower Waverly, Holman’s Barber Shop reflects Black barber shops’ vital roles within local African American communities and is one of the only mid-century Black-owned barber shops in Columbia known to still stand and have integrity to its earliest years of operation. As reflected in the shop’s listing in the Negro Traveler’s Green Book, Holman’s provided Black Columbians and other African Americans with an alternative public space where patrons could meet, freely converse, and receive quality, convenient service without fear of the harassment and degradation that often awaited them in the white-controlled spaces of mid-century Columbia. The operation of Ret’s Beauty Box and later the Modernistic Beauty Salon in the other half of the building provides a parallel story of beauty care, social history, and upward economic mobility for Black women. The building endures as a reminder of Black entrepreneurship in the face as adversity and of African Americans’ broader resistance to the system of segregation. Read More

- Chappelle Tourist Home (Waverly Historic District)

- Hilltop Hotel (Harper’s Ferry Historic District)

- Lewis Clark Hotel (Lewiston Historic District)

- North Carolina Green Book Sites

- North Carolina African American Heritage Commission

- Tennessee Green Book Sites

- Virginia Green Book Sites

- South Carolina Green Book Sites

- South Carolina Green Book Project

- Connecticut Green Book Sites

- Texas Green Book Project

- South Dakota Green Book Sites

- Utah Green Book Project

- Vermont Green Book Sites

- Information for the article was compiled from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Smithsonian Green Book Project.

- The Green Book Properties Listed in the National Register of Historic Places was researched and compiled by National Council for Preservation Education intern Alicia Guzmán.