Last updated: January 21, 2026

Article

The A.G. Gaston Motel and the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument

In the face of violent state repression, the modern civil rights movement sought equal rights and constitutional equality at the national level. Churches, courthouses, schools, parks, and a myriad of other landmarks make up the constellation of sites, both large and small, where moments of change occurred. One of these sites was the A.G. Gaston Motel, a significant site of civil rights activities in 1963 that served as the headquarters of the campaign to desegregate public accommodations in Birmingham, Alabama. From the motel, leaders made critical decisions that advanced the cause of civil rights locally and shaped events and legislation nationally.

The A.G. Gaston Motel

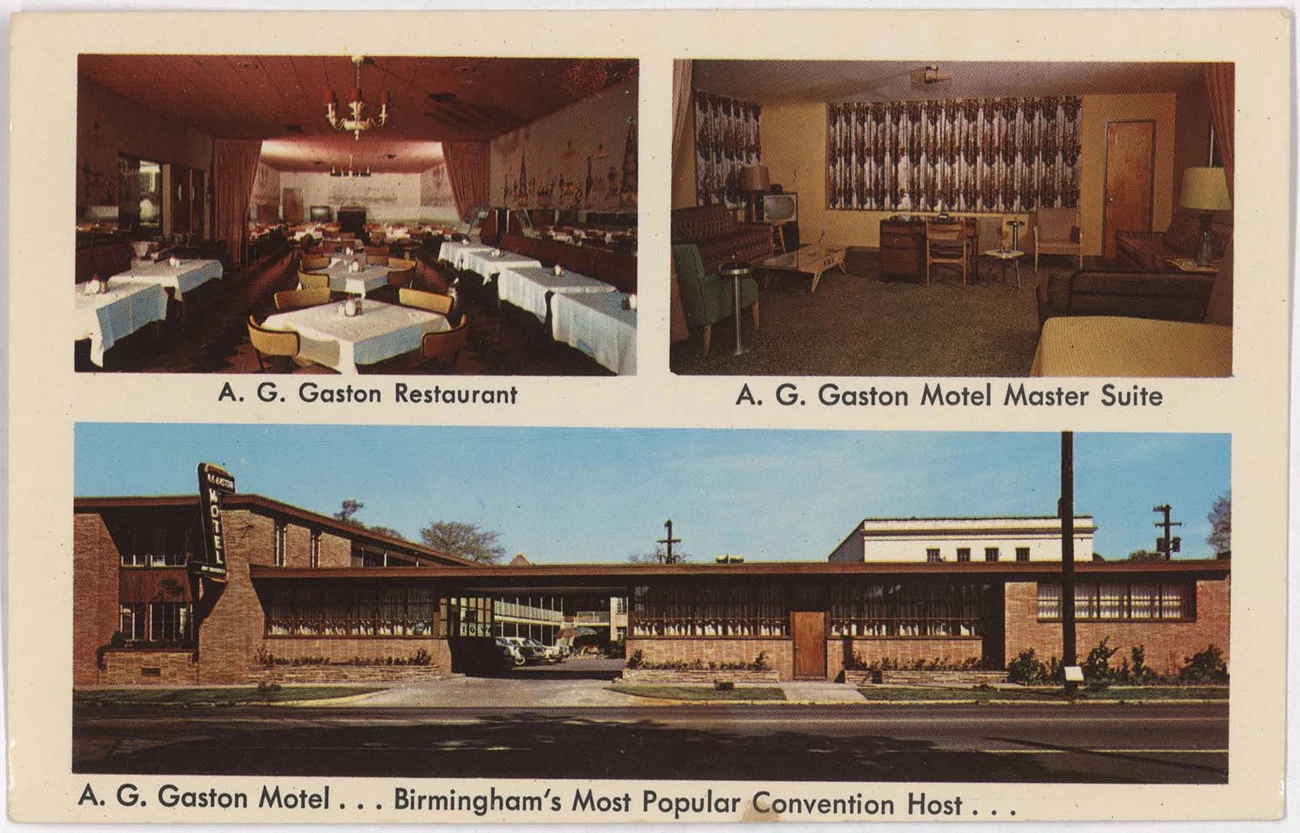

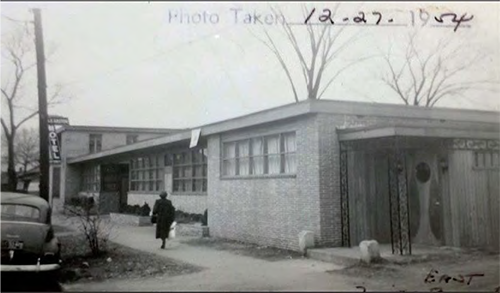

The A.G. Gaston Motel, built by prominent African American businessman and entrepreneur, Arthur George Gaston (1892-1996), provided first-class lodging and dining in Birmingham, Alabama, to African American travelers. Designed by Birmingham-based architect Stanley B. Echols, the motel opened in 1954 and occupies a 0.88-acre parcel at 1510 Fifth Avenue North within the city center.

Jefferson County Board of Equalization Records, from Birmingham Public Library

The surrounding landscape was characterized by an interior courtyard with a small landscaped island and outdoor furniture; a parking court; a raised brick tree planter with a mature tree likely maintained during construction; a Z-shaped motel sign attached to the top of the west end of the front façade; and planters along the front façade facing the street. The courtyard patio was located towards the back of the property away from the street and composed of brick pavers in a running bond pattern oriented north-south. Several sets of metal tables and chairs provided outdoor space for visitors. Images from the early 1960s depict a planting bed, edged in sawtooth brick, to the east of the patio. A concrete walkway separated the east side of the planting bed from the adjacent parking area. Scattered shrubs and a birdbath decorated the courtyard.

The Birmingham Campaign

The modern Civil Rights movement followed southern-state defiance of the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 that ruled segregation was unconstitutional. While some state and local governments tried to maintain the status quo of systemic racism and oppression, including racial segregation of public accommodations, civil rights groups and allies organized to address racial injustice and promote equality.In April 1963, Project C began by boycotting downtown department stores and occupying lunch counters, resulting in a small number of arrests. The movement built towards larger marches, the first of which began in the courtyard of the A.G. Gaston Motel on April 6, 1963. The marchers planned to reach city hall, but were stopped short by police at nearby Kelly Ingram Park.

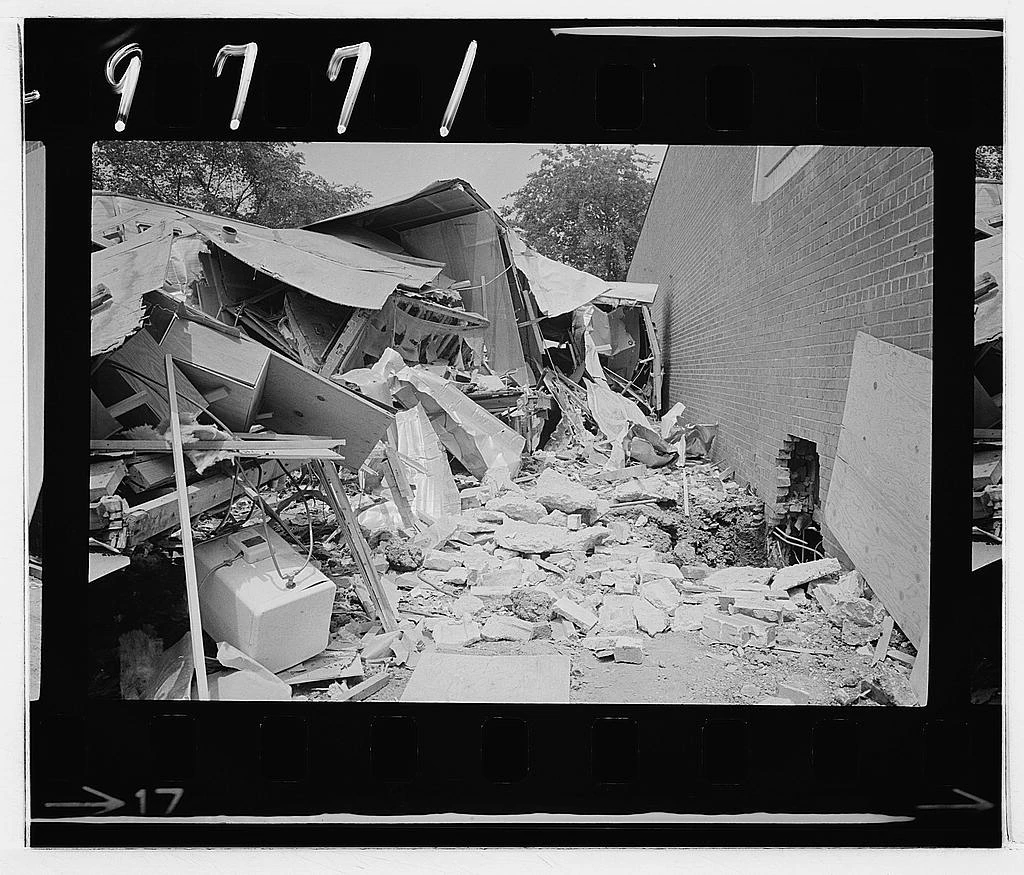

On May 10, 1963, the A.G. Gaston Motel was the site to announce the compromise between local white business owners, city officials, and civil rights leaders. The truce addressed some of the issues in the original list of demands issued by the Birmingham Campaign. Rather than the originally called for immediate desegregation of lunch counters, restrooms, fitting rooms, and other facilities such as drinking fountains, and the hiring of more black workers, the compromise established a longer timeline to desegregate the city.

Violent attacks would continue in the city of Birmingham, including the tragic bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, that killed four young girls. Nonetheless, efforts to desegregate the city continued slowly over the following months. These events in Birmingham created significant public pressure that helped lead to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed into law on July 2, 1964, by Lyndon Johnson.

The A.G. Gaston Motel Today

The A.G. Gaston Motel was an important resource in the realization of the Birmingham Campaign to help end racial segregation in public accommodations in the city with effects far beyond city limits. The motel housed strategy sessions, meetings, and press conferences, in addition to providing lodging and social space.A.G. Gaston modernized and expanded the motel in 1968, adding a supper club and other amenities. Business declined in the 1970s and in 1982 Gaston converted the motel into housing for the elderly, which functioned until 1996. The property has since been vacant.

Carol M. Highsmith, February 28, 2010, Library of Congress

In 2016 a Historic Structures Report was completed by Lord Aeck Sargent for the A.G. Gaston Motel and a Cultural Landscape Report was completed by WLA Studio in 2019 to inform future treatment decisions by managers. NPS and the City of Birmingham plan to develop the A.G. Gaston motel site for heritage tourism, commemoration, and interpretation for the public. With the other resources of the district, the A.G. Gaston motel will offer visitors an opportunity to commemorate and connect with the events of the Birmingham Civil Rights Movement.

A project through the African American Civil Rights Grant Program, which works to document, interpret, and preserve the sites and stories related to the African American struggle to gain equal rights, funded recent work to document oral histories related to the significance of the A.G. Gaston Motel. The project focused on providing information to new audiences wishing to gain a deeper understanding regarding the historic significance of the Gaston Motel as a civil rights site.

- Establishment of the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument

- History & Culture, Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument

- National Register of Historic Places, Birmingham Civil Rights Historic District, Birmingham, Alabama, National Register nomination #06000940

- A.G. Gaston Motel, National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument Guide, National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Birmingham Campaign, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University

- A.G. Gaston: The Man and His Legacy, Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Exhibition

- WLA Studio, A.G. Gaston Motel Cultural Landscape Report, Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, 2019

Tags

- birmingham civil rights national monument

- cultural landscape

- civil rights

- birmingham

- southern christian leadership conference

- martin luther king jr.

- gaston motel

- civil rights movement

- kelly ingram park

- alabama

- civil rights act of 1964

- motel

- african american history

- ser

- featured article

- spotlight

- african american civil rights

- historic preservation fund

- historic preservation grants