Last updated: December 28, 2022

Article

Stratotype Inventory—Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, Colorado

NPS photo by Patrick Myers.

Introduction

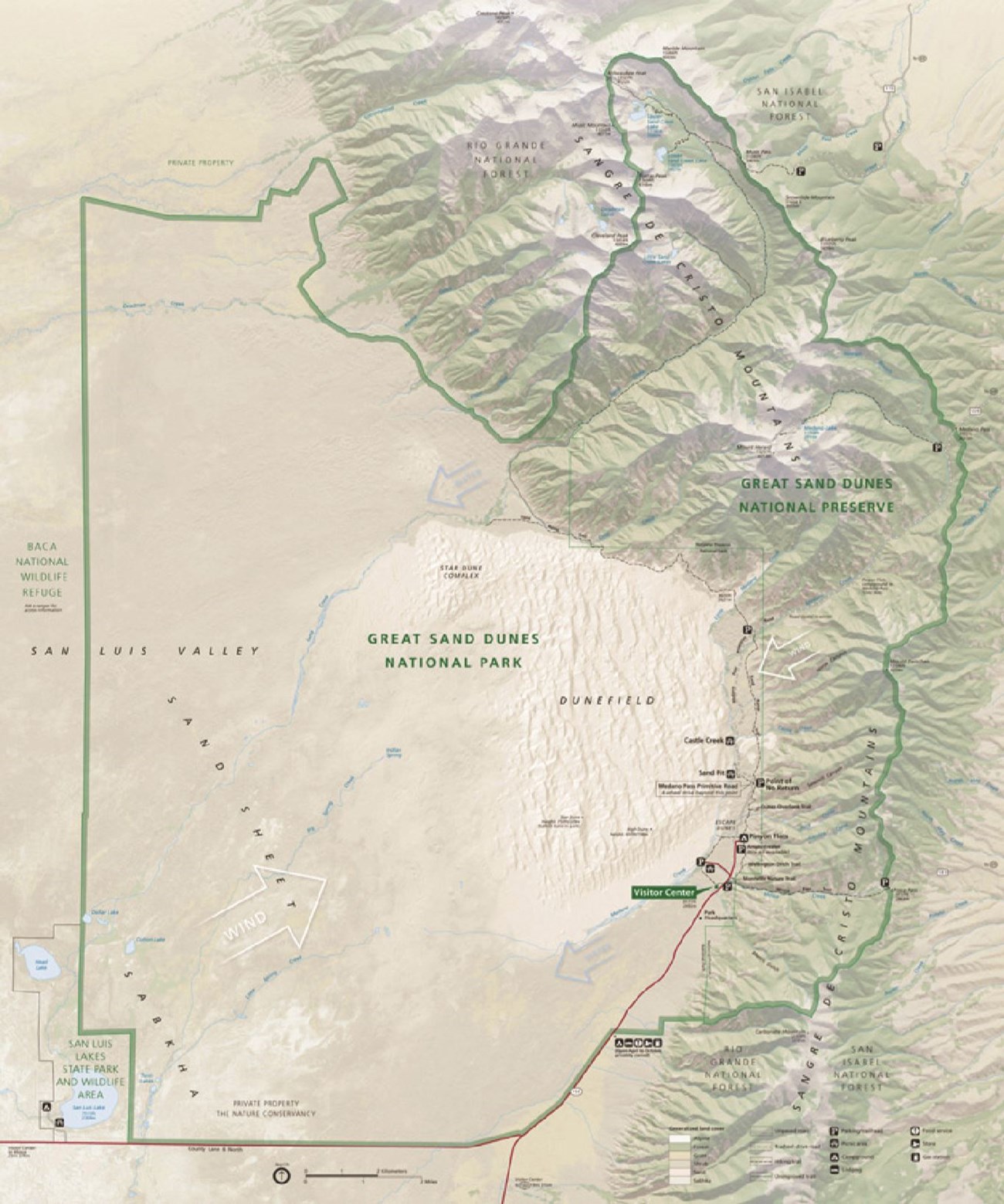

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve (GRSA) is located in the San Luis Valley of Colorado and is home to the tallest sand dunes in North America, with some dunes rising 230 m (750 ft) above the valley floor (Figure 23). GRSA was originally established as a national monument March 17, 1932 and was redesignated as a national park and national preserve November 22, 2000. The national park encompasses 43,423.5 hectares (107,302 acres) of land, includes an 33,994 hectare (84,000 acre) dune field, alpine lakes, tundra, mountain peaks exceeding 3,962 m (13,000 ft), ancient spruce and pine forests, large strands of aspen and cottonwood, grasslands, and wetlands (Anderson 2017; Graham 2006).

NPS image.

Significance and Geologic Resource Values

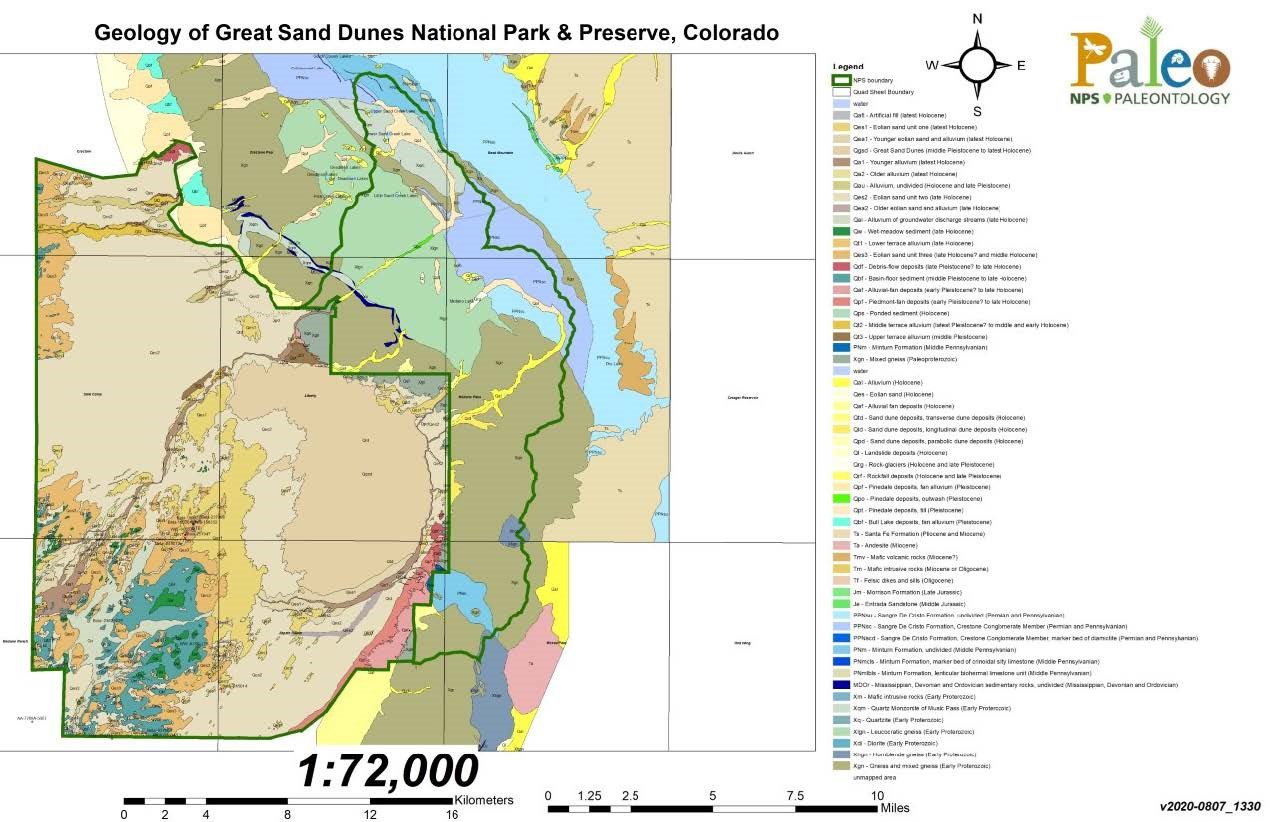

The geology of GRSA and the Sangre de Cristo Mountains consists of Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks, Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, Tertiary igneous and sedimentary rocks, and unconsolidated Quaternary sediments (Figure 24; Graham 2006). Precambrian rocks span the Early Proterozoic (2.5 to 1.6 billion years ago) and consist of quartz monzonite, diorite, and gneiss. Paleozoic and Mesozoic (320 to 146 million years ago) exposures are primarily shale, sandstone and conglomerate of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Middle Jurassic Entrada Sandstone, Pennsylvanian Minturn Formation, and the Pennsylvanian–Permian Sangre de Cristo Formation. Mississippian, Devonian, and Ordovician strata (485 to 323 million years ago) include the Lower Mississippian Leadville Limestone, the Mississippian(?) to Devonian Chaffee Group, the Upper Ordovician Fremont Dolomite, the Middle Ordovician Harding Sandstone, and the Lower Ordovician Manitou Limestone (Graham 2006). Silurian age rocks are not present in the region, and only rare exposures of the Cambrian Sawatch Quartzite are present. Tertiary rocks in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains consist of Oligocene and Miocene igneous rocks and the sedimentary rocks of the Miocene–Pliocene Santa Fe Formation (Graham 2006). A variety of unconsolidated Quaternary-age glacial, aeolian, and alluvial deposits have been mapped in GRSA and the western flank of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains (Lindsey et al. 1986).

NPS image.

Stratotypes in Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

As of the writing of this paper, there are no designated type formations identified within the boundaries of GRSA. A list of stratotypes located within 48 km (30 mi) of park boundaries is included here for reference. These nearby stratotypes include:

- Pennsylvanian–Permian Sangre de Cristo Formation (type area)

- Crestone Conglomerate Member of the Sangre de Cristo Formation (reference section)

- Pliocene–Pleistocene Alamosa Formation (type area)

Type Section Inventory Report—Rocky Mountain Inventory & Monitoring Network

The information on this page is excerpted from a report covering six parks within the Rocky Mountain Inventory and Monitoring Network (ROMN):

- Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado

- Glacier National Park, Montana

- Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana

- Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, Colorado

- Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana

- Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

The full Network report is available in digital format from https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2283702

Please cite this publication as:

- Henderson, T., V. L. Santucci, T. Connors, and J. S. Tweet. 2020. National Park Service geologic type section inventory: Rocky Mountain Inventory & Monitoring Network. Natural Resource Report NPS/ROMN/NRR—2020/2215. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Geodiversity Atlas—Rocky Mountain Network Index

Leave No Trace—Protect Type Sections for Science

Many type sections and paleontological sites are vunerable to damage from careless visitation and over-use. Be sure to practice Leave No Trace princples whenever you are in the outdoors. Of particular importance at geoheritage sites is to:

-

Travel and camp on durable surfaces, and

-

Leave what you find.

If you see signs of vandalism or someone acting inappropriately during your visit to a park site, please contact a ranger at the park or make a report through NPS Investigative Services.

Related Links

- Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, Colorado—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- Geologic Time Scale

- America's Geoheritage

- NPS Paleontological Resource Inventory

- NPS Geologic Resources Inventory

- NPS Geodiversity Atlas