Last updated: June 6, 2024

Article

Military Movements and Uses on El Camino Real de los Tejas

In the early sixteenth century, Spanish trading posts and settlements remained primarily in the Caribbean and densely populated regions of Central Mexico and Peru. As European and Indigenous nations competed for control over trade routes and territory in the Americas, Spanish forces established military forts—or presidios—to protect their claims.

By the end of the sixteenth century, the British and French made attempts to settle parts of what is now the United States. Spanish forces advanced north from Mexico City, sending a colonizing expedition to New Mexico in 1598. Almost a century later, prompted by fears of French colonization, Spaniards began founding missions in Texas. Missions were religious complexes dedicated to teaching Indigenous peoples Christianity and other practices considered “civilized” by Spaniards. Along with presidios, missions were one of the ways that Spaniards secured their territorial claims; unlike presidios, though, missions were focused on cultivating relationships with local Indigenous groups.

NPS Photo

Goliad State Park

Originally located in Matagorda Bay, Spanish authorities commissioned the Presidio La Bahía in response to an early and short-lived French colony established in the area in the 1680s. This settlement prompted Spanish movements into the region east of the Rio Grande, particularly to East Texas, where Mission San Francisco de los Tejas was founded in 1690.

The threat of further French colonization of the Gulf Coast prompted Spanish settlement as far east as the Red River, which became a de facto border between Spain and France in North America.

Located on either side of Sibley Lake, Los Adaes and Fort St. Jean Baptiste show both Spanish and French presence in Louisiana. These sites functioned as trading posts, military garrisons, and settlements for the two rivals until Spain gained full control of the Louisiana Territory (the western portion of the Mississippi River basin) in 1762.

NPS Photo

Fort St. Jean Baptiste State Historic Site

NPS Photo

Los Adaes State Historic Site

NPS Photo

San Antonio

Founded in 1718, Mission San Antonio de Valero served the traditional purpose of a Spanish mission, housing as many as 300 Indigenous residents, many from Coahuiltecan groups like Payayas, Jarames, and Pamayas. Only a few days after the mission’s founding, builders began constructing a presidio a mile to the north, a fortified adobe structure that came to be known as San Antonio de Béxar. The settlement that grew up around the presidio was home to San Antonio’s first civilian residents. The combination of mission, presidio, and villa (town) led San Antonio to become the capital of Spanish Texas in 1772. Around this time, San Antonio saw a rapid expansion of the garrison, solidifying Spanish presence in the area and expanding permanent settlement in Texas.

San Antonio is also the site of perhaps the most famous Spanish colonial tourist attraction in North America: Mission San Antonio de Valero, more commonly known as the Alamo. When Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, Texas became part of Mexico. Tensions mounted in the 1830s as Anglo Texans resented the prohibition of slavery in the young republic and sought freedom from Mexican rule. During their war for independence, Mexican federal troops defeated and killed a group of Texan rebels—including prominent figures like Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie—at the Battle of the Alamo (1836). “Remember the Alamo” became a rallying cry in the ensuing conflict, including at the decisive Battle of San Jacinto. The expression continues to play a role in modern Texan identity.

Photo/Louisiana State Historic Site

Fort Jesup: A New Country and a New Border

In 1803, much to Spain’s dismay, France sold the eastern Louisiana Territory to the United States. The Louisiana Purchase—as it was commonly called—reestablished a state border in eastern Texas, along the Sabine River. The American government built Fort Jesup in 1822 to defend the nation’s southwestern frontier and the important port of New Orleans. Since the United States was not directly involved in the Texas Revolution, this installation did not see much military action. A decade later, however, it would serve as a staging area for troops headed to the Mexican-American War (1846–48). No longer needed as a border outpost, Fort Jesup was abandoned in 1846.

Briscoe Center Documents

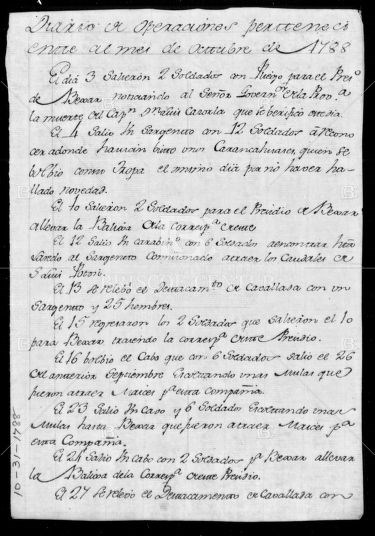

Like soldiers today, military personnel in the territories of New Spain and northern Mexico made regular reports to their superiors and political leaders, providing details about training, supplies, relations with Indigenous groups, and happenings around the presidios. These reports were sent to Mexico City, as well as the local administration in Texas. Many of these documents are preserved in the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin for use by historians studying the Spanish and Mexican periods in the American Southwest. Military reports offer insight into the settlement of the region, as well as conflicts between colonial powers and nation states. These documents also show how relationships between Indigenous groups and settlers changed over time.

Log Translation

Log of operations pertaining to the month of October, 1788.

On the third, two privates left with a jacket for the Presidio of Bexxar, caring news of the senior governor of the province, regarding the death of Captain Don Luis Cazorla, which occurred on this day.

On the fourth, one sergeant and 12 privates set out to reconnoiter where some Carancahuases had been seen. The sergeant returned with his troops on the same day, because he had found nothing.

On the 10th, two privates set out for the Presidio Bexar to carry the pouch with the correspondence from this Presidio.

On the 12th, a carabiner and six privates set out for Laredo to meet the sergeant commission to bring the payroll from San Louis Potosi.

On the 13th, the horse, her detachment was relieved by a sergeant and 25 men.

On the 15th, the two privates returned, who had set out on the 10th for Bexxar caring the correspondence from this Presidio.

On the 16th, the corporal returned to, along with six privates, headset out last September 26th escorting some mules went to bring corn for this company.

On the 23rd, a corporal and six privates set out for Bexxar, escorting, some mules, which had gone to bring corn for this company.

On the 27th the horse herd detachment was relieved by a sergeant and 25 men.

On the 30th, the corporal returned who, along with two privates had left on the 24th for San Antonio de Bexxar, carrying the correspondence from this Presidio, and escorting Lieutenant Dan Manuel de Espadas, interim commissioner of this, aforesaid Presidio.

Bahia, October 31, 1788.

Manuel de Espadas

Report 10.31.1788

Military officials were required to send a monthly report like this one from La Bahia, describing all military exercises and operations at the presidio.

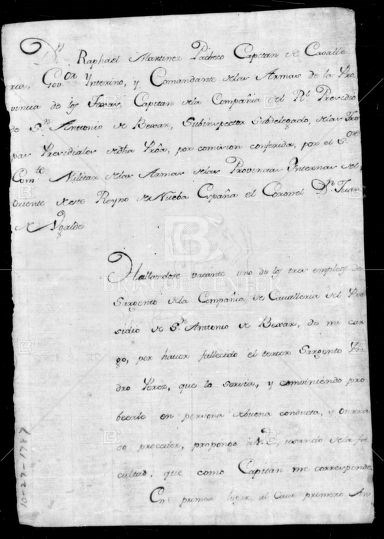

Nominations for Military Appointments 10.27.1787

Sent from the Captain of the Calvary and interim governor of the province of Texas, this letter to the governor of New Spain lists three possible candidates to for promotion to sergeant at the Presidio of San Antonio. This letter summarizes the military service of the each of the men, praising their good conduct and noting that each can read and write—a rare skill at the time.

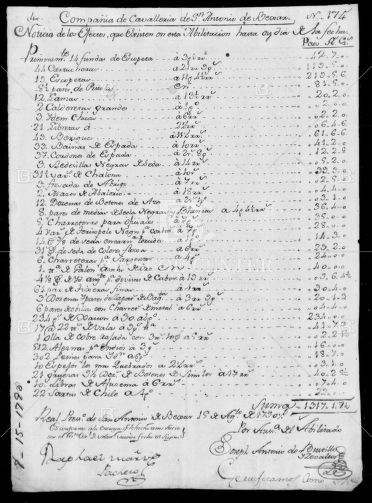

Inventory 8.15.1790

This inventory of military supplies in the presidio of San Antonio de Béxar was compiled both for the governor and the new commander of the presidio. The back is signed by two witnesses who attest to the validity of the report.

While many different types of people used and continue to use El Camino Real de los Tejas, military actions played an outsized role in the trail’s history. This legacy is perhaps most visible in San Antonio, where the remnants of the Alamo and Presidio San Antonio de Béxar dominate the city center. Lackland Air Force Base and Fort Sam Houston attest to the city’s present-day military importance. Now, as in the past, the presence of a military force has brought families and commerce along with it, creating connections and encouraging new relationships along the way.

(Special thanks to UNM PhD candidate Meghann Chavez for compiling this information.)