Last updated: July 31, 2019

Lesson Plan

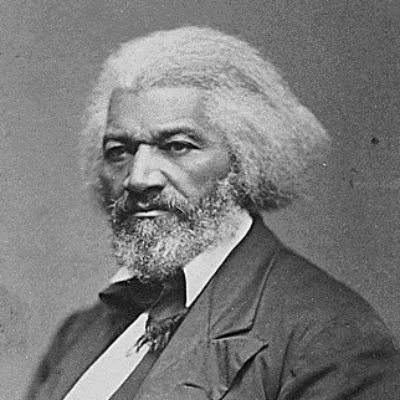

Frederick Douglass, The Educator of Anacostia: “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.”

- Grade Level:

- Middle School: Sixth Grade through Eighth Grade

- Subject:

- Literacy and Language Arts,Science,Social Studies

- Lesson Duration:

- 90 Minutes

- Common Core Standards:

- 6-8.RH.2, 6-8.RH.6, 6-8.RH.7, 6-8.RH.9

- Thinking Skills:

- Remembering: Recalling or recognizing information ideas, and principles. Applying: Apply an abstract idea in a concrete situation to solve a problem or relate it to a prior experience. Analyzing: Break down a concept or idea into parts and show the relationships among the parts. Creating: Bring together parts (elements, compounds) of knowledge to form a whole and build relationships for NEW situations.

Essential Question

How did Frederick Douglass use literacy and his collection of artifacts to educate his community and celebrate his accomplishments?

Este plan de clase con actividades incluido también está disponible en español.

Objective

1. Learn how Douglass's early life inspired his respect for education.

2. Discover ways that Douglass educated his community about science and history.

3. Apply archeological techniques to "read" primary sources.

4. Practice skills in observation, inference, communication, and critical thinking.

Background

What is Archeology?

Archeology is the study of the human past through material remains. Archeologists investigate the way people lived in the recent and deep past through the artifacts they used and the landscapes they created. Historical archeologists use artifacts and documents such as maps, diaries, church records, letters, and business records, to piece together stories of those who lived in the past. Archeology provides valuable information about the people who lived before us, even if they didn't leave any written documents behind. In such cases, archeologists rely on physical evidence, such as buildings in ruins, altered landscapes, and piles of trash.

An essential part of studying archeological evidence is context. The context, or association of an artifact or site with other evidence (e.g., soil, deposited layers, other excavated material, historical documents), tells us how old something is and with whom it is associated. Disrupting a site without proper documentation can cause artifacts to lose their context and without context, an artifact or site loses its wealth of information and learning power. Remember to remind students if they see an artifact on the ground to leave it where it is or to tell a park ranger.

Archeologists’ research uncovers evidence and information that provides ways to teach history through hands-on, sensory based lessons. Along with using archeological evidence in the classroom, the scientific exploration of archeology offers a more profound and personal connection for students with their history.

People have always been fascinated by the material others have left behind. Frederick Douglass expressed the same curiosity throughout his life. He collected artifacts from past cultures, such as ancient indigenous stone tools and glass beads. In the same way Douglass used his collection of artifacts to learn, students will use the same artifacts to learn about the themes of Douglass’s life and the archeological process.

Slavery and Abolition

Frederick Douglass began his life enslaved in Maryland. Slavery lasted 250 years in the American colonies and eventual United States, from the 17th- to the mid-19th century. It is estimated that the Transatlantic Slave Trade was responsible for the forced migration of over 12 million Africans, though historians and archeologists believe that number to be higher. Enslaved people were brought to the US colonies through different routes, many being traded through the Caribbean. Enslaved people were forced to cultivate the many cash crops that built the U.S. economy. The process of the slave trade was destabilizing to African families and personal relationships. Most Africans would never see their families again and were traded to regions with other Africans whom they did not share language or cultural practices.

Although the practice of slavery has been documented throughout human history, slavery in the U.S. was a unique practice all its own. Slavery in the U.S. was known as “chattel slavery” because of its complete dehumanization of enslaved people. Chattel slavery was a terrorizing system that used both violence and psychological torment to control large populations of enslaved people. One of the most effective forms of control was to limit access to education. Enslaved people were kept illiterate in efforts to prevent them from organizing collective resistance.

Education is a gateway to new ideas and communication; slave owners were acutely aware of how dangerous these factors were to the balance of the fragile system of slavery. This concept was key to Frederick Douglass’s life.

Although the “peculiar institution” (as slavery was sometimes referred) was a pillar of economic life in the US, it was not wholly accepted and supported by everyone. Political, religious, and social activists who outwardly opposed slavery were known as abolitionists. Through their efforts, slavery was abolished in the many Northern states by the 19th century. This allowed for more open political support to end slavery across the country. Many notable abolitionists were freedmen and fugitive enslaved peoples living in Northern states or Canada. One of the most prolific efforts of the abolition movement was the Underground Railroad, a network of abolition sympathizers who helped enslaved people escape Southern states to freedom in the Northern states and Canada through a series of “stops” along this symbolic railroad.

While the majority of the abolitionist movement was rooted in the Northern region of the U.S., slavery was by no means completely abolished across the Northern state borders. The impacts of slavery were still entrenched in these states’ economies and social structures. By 1810, a fourth of the black population in Northern states were enslaved. This statistic is surprising considering the first Northern emancipation legislation was passed through the Vermont state constitution in 1777. The existence of slavery in the North left runaways, formerly enslaved people, and free blacks in a constant state of fear and danger. Although he escaped slavery as a young man, Douglass would spend most of his life navigating the dangers of recapture.

Civil War and Post-Emancipation Period

In 1860, Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party won the presidency with an anti-slavery platform, sparking the secession of eleven southern states and eventually the Civil War. The Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War in 1865 led to the passing of the 13th Amendment that officially ended slavery in the United States.

Formerly enslaved people then faced a whole new world of difficulties. The influx of newly-freed African Americans paired with the physical and mental destruction of the Civil War caused concern for the United States government, prompting officials to create initiatives to integrate formerly enslaved people into society. These initiatives became known as the era of Reconstruction. Two of the most crucial Reconstruction era actions included the passing of the 14th and 15th Amendments. These new amendments bestowed rights that were once denied for generations of enslaved people, including citizenship and the right to vote.

Although Reconstruction was initially a period of hope, the ideals of Reconstruction were never fully realized. This era should have been a time of rebuilding and healing, but the reality was a tumultuous time of resentment by most whites towards African Americans who were trying to exercise their new rights as citizens. Initiatives, such as the Freedmen's Bureau, the Reconstruction Amendments, and the election of the first African-American U.S. Congressman, were monumental yet the gains they provided were eventually lost within this social ideology.

For most African Americans, true freedom and independence hinged on access to education. Many states developed new restrictions to bar Africans Americans from voting and attending school. Frederick Douglass and his contemporaries used the essential tools of literacy and vocational training to uplift and help African Americans to thrive during this difficult time.

Frederick Douglass’s Life

Frederick Douglass, originally Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, was born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland. Because enslaved people were viewed as property, his exact birthday was not documented though he knew he was born sometime in February of 1818. As a child, Douglass was hired out in Baltimore as a companion of his master's son to conduct errands and chores in the household.

At an early age, Douglass developed both a deep love and respect for literacy. It was rare for an enslaved person to learn how to read and write. He saw that literacy was the door to knowledge and therefore freedom. He became determined to teach himself how to read and most importantly how to write. Douglass viewed books as not just a vehicle for learning but also the sharing of ideas. When Douglass was a young man, he was sent back to the plantation where he was born to be a field hand. While there he seized every opportunity to educate his fellow enslaved people.

Soon Douglass became focused on planning his escape and his long road to freedom. In 1838, he met a young, free woman in Baltimore named Anna Murray. Murray helped Douglass plan and pay for his escape to New York, where the two were eventually married. After their wedding, Frederick and Anna moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts where they started a family. While in New Bedford, Douglass began giving speeches to abolitionist groups on his life as an enslaved person and his struggle to escape. Douglass’s excellent oratory skills quickly made him a very well respected and valued member of the New England Abolitionist Movement. He landed a job as an agent for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and traveled the North and Midwest giving speeches. His work with the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society was one of the earliest opportunities for Douglass to educate a broader national community.

In 1845, Douglass made a life-changing choice to publish the autobiography of his time in enslavement, titled The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. The narrative resulted in both great success and great danger for Douglass and his family, because the book used real names and places and could have led to the Douglass’ recapture. To avoid these dangers, Douglass first moved his family further north to Rochester, New York then went abroad for two years. While in the United Kingdom, he gave many talks and book tours. The publication of his book and the time he spent abroad was Douglass’s first opportunity to educate an international community.

Eventually, Douglass returned home and lived in Rochester, where he became further engaged in the abolitionist movement and other social reforms, including the women’s suffrage movement. While in Rochester, Douglass purchased a printing press and ran his own newspaper, The North Star. The North Star was another initiative that Douglass used to educate his community on the injustices of slavery and the treatment of free blacks. In 1855, Douglass published his second memoir, My Bondage and My Freedom, where he elaborated further on his first book and discussed the effects of racial oppression in the North. Douglass’s goal with writing his memoirs was to share his experiences and educate his fellow man about the atrocities of slavery. These books became a great symbol of Douglass’s desire to teach and help improve the lives of the African American community. Education would become the theme that Douglass would celebrate in every aspect of his life.

After the Civil War ended, Douglass became an appointed government official, statesman, and leader during the Reconstruction period. Some of his government appointments included: secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (a commission to review the 1871 annexation of Santo Domingo to the US), legislative council member of the DC Territorial Government, board member of Howard University, and president of the Freedman's Bank.

In 1872, Douglass moved his family to Washington, DC to be close to the epicenter of America’s political movements. He purchased his final home in 1877, which he named Cedar Hill, in the neighborhood of Anacostia. Two years after Anna Murray Douglass’s death in 1882, Frederick Douglass married Helen Pitts. Pitts was a white Quaker from Western New York. She was an abolitionist and an activist for women's suffrage. Both of Douglass’s wives were influential in the abolition movement and social reform. While in DC, Douglass served as US Marshall for District of Columbia (1877), Recorder of Deeds for District of Columbia (1881), and Minister to Haiti (1889).

Douglass’s Cedar Hill home became an expansive estate full of trees, orchards, and vegetable gardens. Cedar Hill allowed Douglass to enjoy nature while also being at the center of post-reconstruction social reforms. He created an open house policy where anyone could visit and discuss topics that ranged between politics, literature, science, and philosophy. Douglass welcomed these discussions because it gave him the opportunity to educate and impart the knowledge gathered throughout his life. In particular, Cedar Hill became a place where Douglass could share the many artifacts he collected from his travels. While serving as the minister to Haiti, he collected scientific specimens, such as coral and shells. While living in Western New York, Douglass became fascinated by indigenous stone tool traditions and collected multiple stone points from the state. Some of these artifacts are featured within this lesson plan activity.

Cedar Hill and Anacostia

Cedar Hill stands atop the center of the DC neighborhood of Anacostia. Anacostia, originally called Uniontown, was one of the first suburbs of DC and was initially a neighborhood for working-class, white dock workers. In 1854, restrictions were passed in Anacostia prohibiting the sale or rental of property to African and Irish Americans. In spite of this policy, a quarter of the community in Anacostia was African American in the late 19th century.

When Douglass first moved to Anacostia, it was a very rural community that was slowly building to be a part of the broader urban sprawl. Quickly, the Douglass estate became a beacon of knowledge in the neighborhood. It provided many people with an opportunity to educate themselves, a right that would have otherwise been out of their reach. Cedar Hill became a center for community gathering and social activism. After Douglass’s death in 1895, Helen Pitts Douglass fought to protect the property, eventually allowing it to become a protected heritage site. Today, Cedar Hill is a national park, known as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. The park serves as a center for future generations to learn about Douglass’s life and his actions towards equality for all people.

Today, the Anacostia neighborhood is predominantly African American and has become a pillar of social activism in the DC region. Anacostia has a long history that celebrates many of the principles that Frederick Douglass lived, such as activism, education, and community organization. The Douglass Home inspires much social activism and is seen as a pilgrimage site. It has become a place where people from all over come to celebrate the continual accomplishments and contributions of African Americans to American history.

Douglass the Educator

Douglass’s early life as an enslaved person drove him to develop a deep respect for education. He worked to surround himself with books and teaching materials. Many of the artifacts found in his home, such as his collection of Native American stone points and marine specimens from the Caribbean, were used to educate himself and his peers. Douglass enthusiastically shared his collection of books and artifacts in efforts to teach his community and provide access to educational material for other African Americans. He inspired many generations to explore all areas of study. Douglass’s collection is used in this lesson to continue and celebrate his legacy as a community educator.

Preparation

Supplies

Pencils, paper, and rulers for each student.

Download and Print

Review the Teachers Guides for activity #1, #2, and #3. Follow the directions in each activity to download and print materials needed for the activity.

3D Modeled Replicas

Link to Frederick Douglass National Historic Site folder on SketchFab.

Decide if you will display the 3D modeled replicas in the classroom on a computer screen, or download and print them.

If you decide to print, make one set for each student or each group of students.

If using the replicas online, students will require computers or tablets to access them on the SketchFab website.

If printing the 3D replicas from the SketchFab website, follow these directions:

- Go to the SketchFab website to the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site folder on SketchFab.

- Click the download tab for each file. For this lesson plan, you will need: FRDO 4130 – Coral from Haiti; VCU 3174, FRDO 2279 – Stemmed Lamoka Point; VCU 3160, FRDO 2281 – Triangular Point; VCU 3154, and FRDO 2280 – Blue glass bead; VCU 3175.

- If printing on site open the model in printer software. If the file is a polygon file or another non compatible file you will need to download MeshMixer and export to an STL format.

- Check the model for any problems.

- Add filament to printer and print.

Materials

Download Teacher's Guide to Activity 1: The Life of Frederick Douglass

Download Teacher's Guide to Activity 2: Frederick Douglass the Collector

Download Teachers Guide to Activity #3: An Interview with Frederick Douglass

Download En Español: Frederick Douglass, el educador de Anacostia

Download En Español: Guía para el profesor Actividad 1: La vida de Frederick Douglass

Download En Español: Guía para el profesor Actividad 2: Frederick Douglass, el coleccionista

Download En Español: Guía para el profesor Actividad 3: Una entrevista con Frederick Douglass

Lesson Hook/Preview

Play for students the NPS audio, Frederick Douglass: The Unbelievable True Story of a Brave and Inspirational Man (6:28), or the NPS video, Frederick Douglass: An American Life (32:47).

Procedure

Step 1: Review the Background Information with the class. Review the vocabulary terms. Discuss as a group: How would Douglass's early life as an enslaved person impact his access to education and his value for learning? What would it have meant for Douglass to share the artifacts he collected from his experiences and travels with his community and family?

Step 2: Distribute supplies. Pass out computers or tablets, or sets of 3D printed replicas.

Step 3: Complete Activities 1, 2, and 3.

Step 4: Conduct a discussion using assessment questions.

Vocabulary

Abolition: The act of officially ending or stopping something. The goal of the abolition movement of the 18th and 19th centuries was to bring an end to chattel slavery, the trading of enslaved peoples.

Activism: The action of using campaigning to bring about political or social change.

Archeology: The study of human history through artifacts and other physical remains.

Artifact: An object made, manipulated, and used by human beings.

Freedman: An enslaved person who is free during pre-emancipation in America; a person who obtains personal, civil, or political liberty.

Observation: A remark, statement, or comment based on something one has seen, heard, or noticed.

Orator: A public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Reconstruction: A period in U.S. history (1865–77) when attempts were made to redress the inequities of slavery and its political, social, and economic legacy; and to solve the problems arising from the readmission to the Union of the 11 states that had seceded at or before the outbreak of war.

Suffrage: The right to vote in political elections.

Assessment Materials

AssessmentUse the following questions to gauge students’ grasp of the material in this lesson plan.

What can we learn about Frederick Douglass from examining the material he kept throughout his life?

How can archeologists and historians use artifacts to learn about individuals and communities?

Can we apply Frederick Douglass’s value for education and his inspiring curiosity for his environment to our everyday lives?

Can you recall a time when you helped someone else learn something new?

Enrichment Activities

Students who want to learn more about Frederick Douglass may wish to explore his own words and reflections:

Douglass, Frederick.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Signet Books, New York, 1845.

Douglass, Frederick.

My Bondage and My Freedom. Miller, Orton & Mulligan, New York, 1855.

Douglass, Frederick.

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape from Bondage, and His Complete History. Collier-Macmillan, 1892.

Related Lessons or Education Materials

NPS Subject Sites