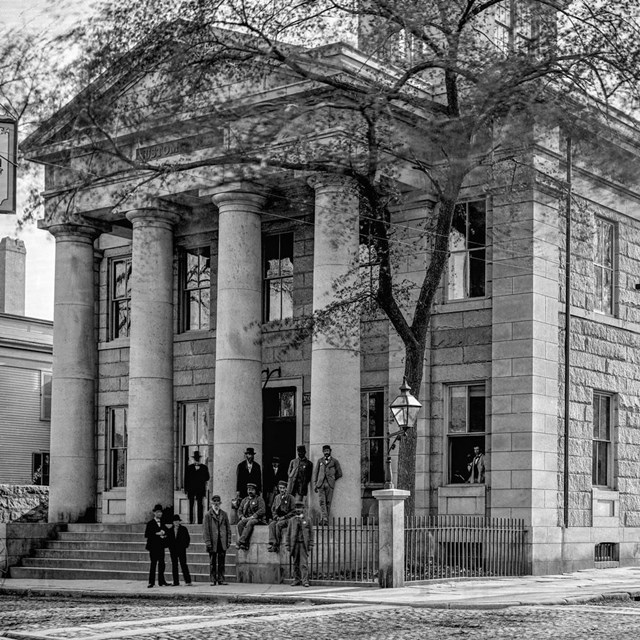

As voyages moved farther offshore in the 19th century, Nantucket’s shallower harbor, obstructing sandbars, and dangerous shoals led to its decline as a whaling port. As voyages increasingly went beyond Cape Horn (Chile) and the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) in search of prey, ships increased in size, and New Beford’s whaling industry swelled because of its amenities. In 1800, 17 ships left from Nantucket compared to the seven from New Bedford. In 1815, Nantucket boasted 50 ships to New Bedford's 10; and in 1820, Nantucket outnumbered New Bedford, 45 to 36. The gap closed quickly thereafter. In 1823, New Bedford passed Nantucket in the number of whaleships departing annually on voyages, and never gave up its lead. With the arrival of the railroad in 1840 and easier access to New York and Boston markets, New Bedford became the wealthiest city in the world. In its heyday, New Bedford's whaling industry influenced its shoreside industry, fashion, architecture, and culture. Today, the city's whaling roots are depicted in its art, industry, and demographics. |

Last updated: October 9, 2024