The world of the ship was isolated, highly structured, racially integrated, and, by the mid-1800s, increasingly populated by captains' wives and children who joined on longer voyages. Though the sea is traditionally understood as romantic landscape, whaling was not a romantic business. In the earliest years of the industry, whalemen were from seafaring communities and were brought up to view the ship as their workplace. In addition to being dirty and dangerous, whaling was monotonous work. Life onboard consisted of long periods of boredom; for weeks, even months, no whales would be seen. The crew would repair gear, write letters, play games and music, and carve scrimshaw — pieces of whale bone or tooth — to pass the time. Food and water would often become foul, and fights would break out among the crew because of the uncomfortable conditions. Men of all ranks and races faced danger from injury, illness, shipwreck, drowning, and piracy. Whale sightings equated to short bursts of excitement as the men rushed to catch the whale, and then kill and process it. Ranks on a Whaleship

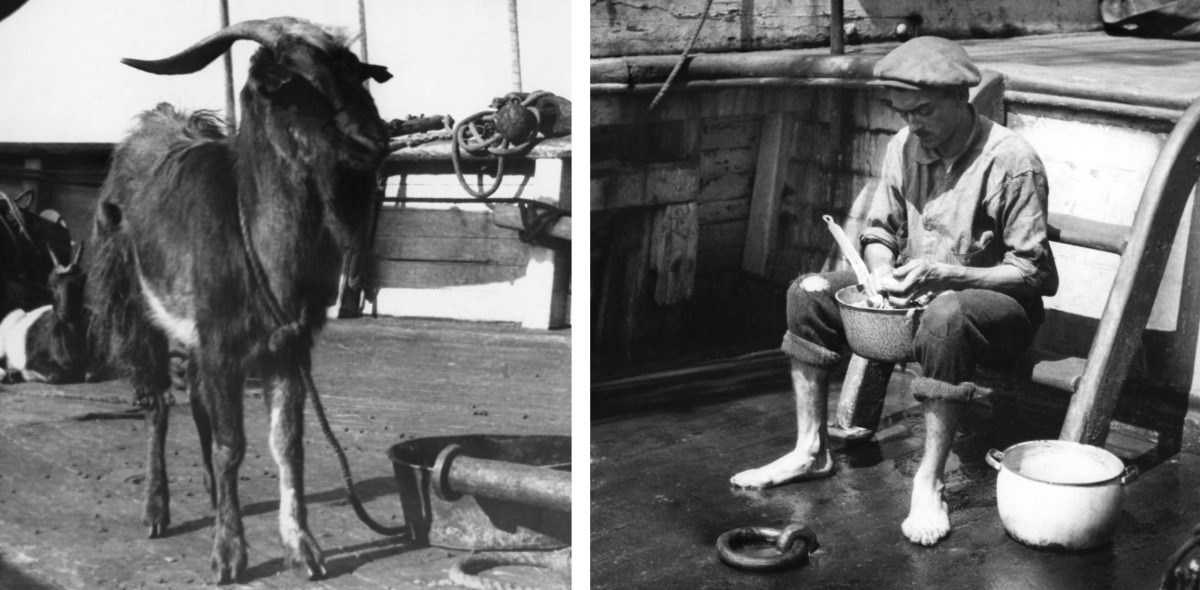

Whalemen ate and slept according to their rank. The captain ate the best meals and slept in the stateroom; deck hands slept in bunks in the forecastle, at the front of the ship. Fresh food ran out quickly: hungry crewmen ate salted meat, bug-infested hardtack, and beans. Crew constantly caught fresh fish, turtles, seabirds, and dolphin. Everyone looked forward to resupply stops at port, where they could bring on fresh fruits and vegetables. Whaleships carried goats, as well as cows, hogs, and chickens, to supply the men with fresh milk, eggs, and meat.

The Slop Chest Whaling was said to be good money — but sailors quickly discovered the truth. They were paid not by a wage, but by a share of profits. A low-ranking sailor might get half a percent of the final take, or profit. The take was determined by the ship’s owner, however, who deducted for the cost of the voyage. Many men got paid in advance, in order to send money home to their families. Whalemen had to pay a share of the ship’s provisions. Any additional supplies that they needed — bandages, medication, clothing, soap, tobacco — had to be bought from the “slop chest,” or the company store. If whalemen bought too many items or took too many advances, they might exceed their take and end up owing money at the end of a voyage!

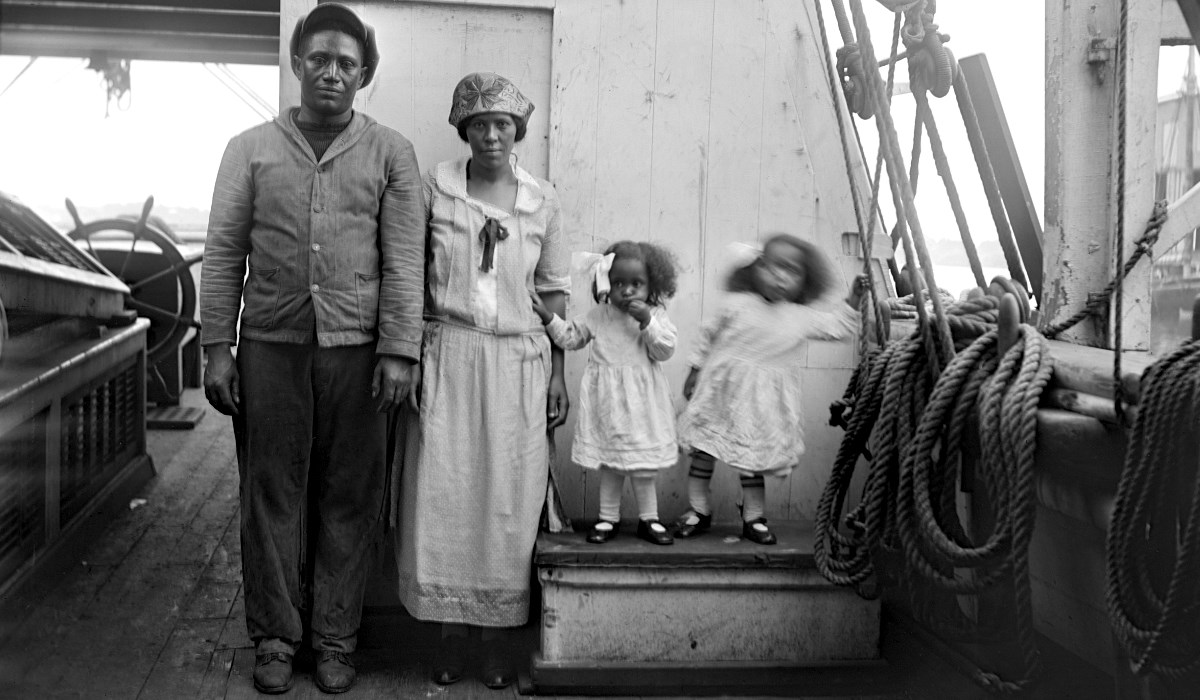

As New Bedford grew to become the world’s largest whaling port, the workforce was increasingly comprised of men from farming and laboring backgrounds. That included men whose options on shore were limited because of their race or background, and immigrants who often landed in New Bedford aboard vessels they had crewed. The community found aboard Yankee whaleships was not replicated anywhere else in America in the 19th century. Men of African ancestry and Native Americans served side-by-side with men whose families had originated in Europe. Pay was based on shipboard position, and opportunities for advancement were largely based on merit and experience. Women on Whaleships By the middle of the 19th century, whale populations had declined. Whaling expeditions grew longer as New Bedford vessels expanded their hunting grounds to the Pacific and Arctic oceans. By 1851, voyages averaged 46 months, which became a hardship on married whalemen. Although most of the men onboard were young and single, most captains were married. Eventually, vessel owners allowed captains to bring their families with them on long voyages. By 1853, there was a captain’s wife on one in five whaleships from New England. A ship with a woman onboard was often called a “hen frigate.” Captains could bring their families, but they were expected to reimburse the ship’s owners for provisions and lodging ($1,000 per voyage in 1895). Onboard, women did laundry, cooked, sewed, wrote, and read. The only whaling task women were allowed to do was call out, “There she blows!” Beyond the walls of the ship, the captains' wives sought company from the wives of other captains in chance meetings at sea. During these "gams," the women would exchange information, books, and presents. Like the whalemen, these women also encountered people, cultural practices, natural phenomena, and animal and plants at exotic locales that most Americans could only read about. Before whaleships headed into the Arctic or Antarctic, some female mariners would get off at resupply ports such as the Hawaiian archipelago or southwest coast of Australia. Among others like themselves, they attempted to recreate their New England world with Protestant churches, missionary activities, and shore communities.

|

Last updated: December 19, 2018