The Lassen area was a meeting point for at least four Native American Indian groups: Atsugewi, Yana, Yahi, and Maidu.

Sharing through StoryTribal members in the Lassen region work with the National Park Service to help visitors understand both modern and historical Tribal culture.

AtsugewiHat Creek was an important thread in the lives of the Atsugewi. This creek was an important fishing ground for the industrious Atsugewi, who spent much of their lives food-gathering to survive in what was often a harsh environment. The Atsugewi were split into two distinct bands, the Atsuge and the Apwaruge. The Atsuge lived, hunted, and fished here in the Hat Creek Valley, while the Apwaruge used valley areas farther eastward. The Atsuge were known as the pine-tree people because their homes and hunting grounds were largely within pine forests. The Apwaruge lived in the dryer juniper-covered landscape. Present-day Pit River TribeThe Pit River Tribe is comprised of eleven autonomous bands: Ajumawi, Atsugewi, Atwamsini, Ilmawi, Astarawi, Hammawi, Hewisedawi, Itsatawi, Aporige, Kosalektawi, and Madesi, that since time immemorial have resided in the area known as the 100-mile square, located in parts of Shasta, Siskiyou, Modoc, and Lassen Counties in the State of California.The Pit River Indians have a varied material culture in response to great variation in elevation, climate, and vegetation of their homeland. Present-day Susanville Indian RancheriaThe anthropological tribes associated with the Rancheria are: Maidu, Paiute, Pit River, and Washoe. The Susanville Indian Rancheria is acknowledged as the recognized tribe for the Rancheria although there are four anthropological tribes involved, each of which is recognized as political entities. The eleven small bands’ of the Pit River Indians have formed and is recognized by the Federal Government as the Pit River Nation. The Maidu Tribes are in the process of forming under the recognition process through the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Greenville Rancheria MaiduThe ancient people that have lived at the foot of Kohm Yah-mah-nee’s (Lassen Peak) southeasterns slopes in the lush mountain meadows and deep evergreen forests call themselves Nah-Kan-Koyom Maidum. This tribe of American Indians was part of a larger tribal complex of the Northeastern Mountain Maidu People. The Mountain Maidu People are part of even larger complex of indigenous Maidu people that includes tribes in an aboriginal territory encompassing lands from Lassen Peak to the edge of the high desert great basin, down the Sierra Mountains, along the foothills of the Sacramento Valley, up the river canyons, and into the mountain meadows. The descendants of the ancient Nah-Kan Koyom People continue to live in their ancestral territory despite the decimation of their people and culture as a result of the conquest and settlement of tribal lands by the non-Indians. Present Day Mountain MaiduGreenville Rancheria | Enterprise Rancheria | Susanville Indian Rancheria

Redding Rancheria Yana & YahiUnder the watchful gaze of the towering sisters Mt. Shasta and Lassen Peak, Tribes such as the Pit River, Wintu, and Yana have lived in harmony with their ancestral lands. The land was bountiful, with a great supply of deer, salmon, and acorns. Each Tribe was distinctive, with their own traditions, beliefs, art, and language. They also had their own government and established relationships with other Tribes, ensuring respect for tribal boundaries and hunting grounds. Present day Redding RancheriaView a documentary about the history of the Redding Rancheria Tribe: With the Strength of our Ancestors.

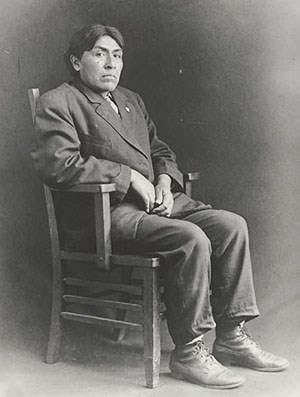

Hearst Museum IshiThe Yahi man known to us today as Ishi is one of the most famous Native Americans of all time. Books, plays, movies, and contemporary art exhibits have explored his life. Yet, we do not even know his true name. Following custom, Ishi refused to speak his name to outsiders without introduction by someone from his tribe. Instead, he was referred to by the word that means “man” in the language of his people, the Yahi. |

Last updated: May 7, 2025