California Department of Fish and Wildlife

NPS/Emily Brouwer This tree-dwelling carnivore is sighted so rarely in the park that is not considered a confirmed resident. However, in January 2021, California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) researchers captured images of a fisher (Pekania pennanti) in the Manzanita Lake Area and just south of the Southwest Entrance.

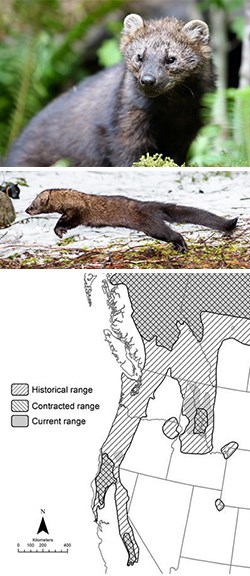

Top: WDFW/John Jacobson; Middle: NPS/Kevin Bacher; Bottom: WDFW Physical DescriptionThe fisher is a member of the weasel family and about the size of a large house cat. Adults are about 4.4 to 13 pounds and 3 to 3.5 feet in length. Males are larger than females. Fishers have dark brown fur with lighter shading on the head, back of the neck, and back. They have a long furry tail (14 to 15 inches long), short rounded ears, and short legs. A fisher may be confused with an American pine marten (Martes americana) which is smaller (between 1.5 to 2.5 feet in length), lighter in color, and has a much shorter tail (6.5 to 7.5 inches). Pine martens are sighted occasionally in the Southwest Area of the park. Ecology and Life HistoryFishers commonly prey upon small and mid-sized mammals, such as snowshoe hares, squirrels, mice, and voles. They also feed on ungulate carrion, fruit, insects, and birds. Fishers are known for their ability to prey upon porcupines. Females give birth when they are two years of age or older, and litter sizes range from 1 to 4 kits. Fishers use uncharacteristically large home ranges for an animal of their size (average sizes are more than 19 square miles in northern portions of its range), with male home ranges typically being twice as large as those of females. Vehicle collisions, and predation by bobcats, coyotes, and cougars are common sources of mortality. Geographic RangeFishers occur only in the boreal and temperate forests of North America. The species once ranged from the state of Washington southward through Oregon and California. Currently, fishers occupy only a small portion of their historical range in the region. Fishers once occurred throughout the forested areas of western and northeastern Washington, and may have also occupied southeastern Washington. However, they were eliminated from the state by the mid-1900s, mainly as a result of over-trapping. The fisher population in California is the largest in the Pacific states. In California, fishers are found in the northern areas of the state and a small, isolated population occurs in the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains.

Top to bottom: California Department of Fish and Wildlife; NPS/Kevin Bacher; Sierra Nevada Adaptive Management Project. Fostering Fisher PopulationsFishers have been extirpated from more than 50% of their previous range and only two native populations survive in California, one near the California-Oregon border and one in the southern Sierra Nevada. Although fishers have faced many threats in the past, biologists are trying to ensure that these fierce little creatures will survive the big challenges ahead. The decline of fisher populations began in the 1800s when there was an increase in the market for luxurious pelts. Many members of the mustelid family including fisher, mink, and otter were hunted nearly to extinction. California banned trapping of fishers in the 1940s but their numbers have continued to decline because of habitat loss from logging, development, and severe forest fires. Other factors contributing to the decline of fisher populations are predation, vehicular strikes, and disease. Northern California and Southern Oregon Fisher PopulationFrom 2009-2011, 40 fishers (24 females, 16 males) were released on a large tract of Sierra Pacific Industries land near Stirling City (east of Chico). Concern about the population's size prompted a cooperative project to translocate fishers into a portion of their historical range in the northern Sierra Nevada and Southern Cascades. Southern Sierra Nevada Fisher PopulationThe Southern Sierra Nevada fisher population was listed in the Federal Register as Endangered in 2020. The range for this small population of 150 to 300 fishers stretches from the Merced River in Yosemite to the southern parts of Sequoia National Forest. Geographical isolation has made this fisher population genetically unique and vulnerable to decline. Washington Fisher ReintroductionIn Washington, the fisher is listed as a state endangered species. Historical over-trapping, incidental mortality, and habitat loss and fragmentation caused the extirpation of fishers in Washington by the mid-1900s. Fisher recovery efforts in Washington began with a reintroduction project on the Olympic Peninsula from 2008 to 2010. Reintroduction projects in the Cascade Mountain Range began in 2015 and are expected to be completed in 2021. This includes fisher reintroduction in Washington national parks: Olympic, North Cascades, and Mount Rainier. |

Last updated: February 19, 2021