NPS photo. A cool breeze sifts into the open windows of the car as we climb along the winding road to Little Cataloochee. We’re part of a park service caravan of fire engines, a law enforcement patrol car, and vans holding eager fire management crew members from the Smokies, Everglades, and Mammoth Cave. The goal today: restore fire to an area of dry, rolling, pine-oak hills where it used to be common. The Canadian Top burn, as it’s called, is the culmination of many months of planning. Each controlled burn in this and other national park units involves a lot of different people to monitor the health of the ecosystem being burned, collect all the tools and safety equipment, and plan the best day to actually put fire on the ground. All of the Fire Management team members—about 30 people on this day—pulled off the road in front of the Little Cataloochee Church and began to unload gear. Already, by 9:00, the temperature had started to climb, and the few clouds lingering on the horizon had disappeared. While some crew members placed a "hose-lay" (fire hose and nozzles) around the historic church, others headed into the woods to clear logs away from the road with chainsaws. The burn boss, Dave Loveland, stood frowning at the sky. The day was getting too hot too quickly, and the air lacked its usual stickiness. At this stage, the burn boss is in charge of deciding whether or not a fire will go off as planned. He or she communicates with the firing boss—the person in charge of actually igniting fire—and the holding boss—the person who makes sure engines, water lines, and supplies are where they need to be to hold the fire in control at all times. About every half hour, they take readings of the weather to monitor the temperature, wind speed and direction, and relative humidity.

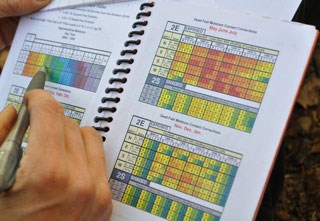

Photo by Warren Bielenberg. On this morning, the temperature seemed to be climbing above what was predicted, while the relative humidity kept dropping. Everyone stood ready, listening to the rustle of dry leaves in the rising heat. Rob Klein, fire ecologist for the park, “spun the weather,” which means he twirled the sling psychrometer (a wet-bulb and regular dry-bulb thermometer set next to one another) to take a reading of relative humidity. The difference in temperature between the wet and dry bulbs after the “swing” reveals how humid the air is. Drier air means the wet thermometer will be much colder than the dry thermometer, because the water has evaporated and cooled the mercury, just as on a hot day your sweat evaporates and cools you!

NPS photo. The amount of humidity in the air determines “probability of ignition” (PIG for short), which is the likelihood that a spark will ignite on contact with fuel. The fire team looks for a PIG that’s not so high that fire could get out of control and not too low that nothing will burn. The ideal is a 30-50% probability of ignition. On this day, the PIG was getting too high for comfort, and the relative humidity had dropped further still. Humidity reaches its lowest point in the late afternoon on clear days, and it had dropped steadily through the morning to 34 percent, very near the cutoff of 30 percent. Each fire has a low-humidity level; if it drops below this, it’s “out of prescription,” or out of the range that the fire plan says is safe for the particular forest type, slope, and area. Low relative humidity can lead to problems controlling how hot and far the fire burns. If the trend of falling humidity continued, we would be out of prescription in just a couple hours. The burn boss turned to the crew, who had been watching him intently, and shook his head. Everyone knew what this meant but stood silently waiting for the verdict. “It’s a no go,” the boss said. He debriefed the crew, explaining the dropping humidity made it too hot, dry, and dangerous to burn today. From here, the crew would wind up the hoses, the burn boss would go back and draft a report, and the prepared site would wait until a better day for fire.

NPS photo. Eventual Burn After another no-go the next week, also due to plunging humidity levels, the crew tried for a third time. This third day turned out to be a beautiful, partly cloudy day, and humidity, wind, and temperatures cooperated. The crew laid the fire hoses around the church, readied the engines, and donned protective helmets to start the burn. Finally, after months of planning and weeks of waiting, low-intensity flames licked at the piled leaf-litter and curled around the base of fire-resistant old trees. With this burn completed, the park was dozens of acres closer to restoring a natural fire regime in Little Cataloochee. |

Last updated: November 12, 2015