Article

Critical Landscape Analysis as a Tool for Public Interpretation: Reassessing Slavery at a Western Maryland Plantation(1)

By Robert C. Chidester

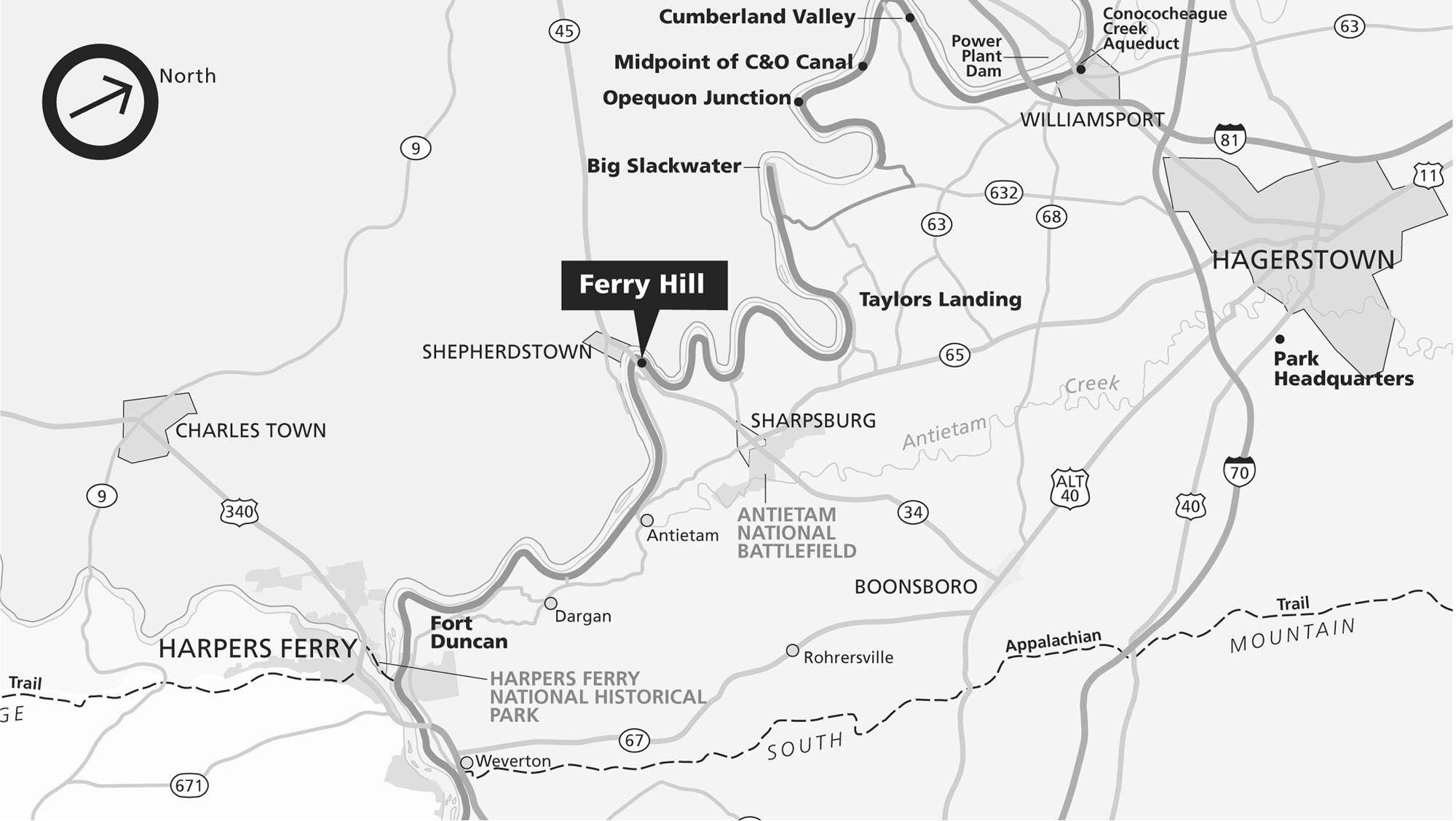

Public historians and archeologists have spent much time in recent years thinking through and discussing the thorny problem of presenting the history of African Americans at public historical sites in the United States. While a great deal of headway has been made at some of the more nationally prominent sites, smaller sites often find themselves struggling against the influence of long-cherished local historical traditions.(2) Such is the case at Ferry Hill Place, a property located in the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (NHP) and currently managed by the National Park Service (NPS). Situated on a horseshoe bend in the Potomac River, Ferry Hill was once the center of a 700-acre plantation in Washington County, Maryland, just across the Potomac from Shepherdstown, West Virginia. (Figure 1) John Blackford, a wealthy farmer and prominent Washington County resident, amassed Ferry Hill Plantation over a period of almost 30 years in the early 19th century.(3)

True to the Southern "Lost Cause" tradition after the Civil War, some previous researchers have described John Blackford as a kindly, paternalistic slave owner. They have noted the fact that Blackford used little overt force to control his slaves, apparently granted some of them a large amount of autonomy, and seems to have been concerned about their health and well-being. Rather than interpreting this evidence as a reflection of the practical concessions that slaveholders necessarily had to make in order to maintain labor discipline and productivity, these scholars have argued instead that slavery at Ferry Hill was not as harsh as elsewhere.(4) This interpretation of Ferry Hill's history is made all the more plausible by its geographical setting in western Maryland, an area dominated by small, diversified plantations with relatively few slaves; in other words, the opposite of the dominant popular conception of the slave South.(5)

While it is true that Blackford did not exactly fit the stereotype of the harsh white southern master, it nevertheless needs to be kept in mind that his relationship with his slaves was defined by the fact that he owned them as chattel. By applying critical landscape analysis to Ferry Hill Plantation, this article suggests the possibility that in addition to overt physical force to control his slaves Blackford used a psychological control technique known as panopticism, or constant, comprehensive surveillance. This argument serves two purposes: first, to dispel the dangerous notion that "slavery was not such a bad life"(6) at Ferry Hill Plantation (and other places like it); and second, to suggest how the public interpretation of antebellum Southern landscapes can incorporate an awareness of the ways in which the power dynamics of American slavery operated in everyday life.

History of Ferry Hill Plantation

John Blackford was born to a prominent family in 1771, in what is now West Virginia. He married Sarah Van Swearingen of Shepherdstown in 1797. The marriage was a profitable one for Blackford, as he thus gained control of the Van Swearingen family's heavily used ferry service across the Potomac River, just below the town. John and Sarah had three children, none of whom lived to adulthood, before Sarah died in 1805, leaving John a young widower.(7)

Soon after, Blackford became involved in local politics. Despite having protested against a possible war with Britain prior to the outbreak of the War of 1812, he enlisted in the militia and fought during the war. Over the next couple of decades he ran for public office several times, and frequently served as a Washington County Justice of the Peace. Blackford also became a businessman, acting as the primary shareholder in the Boonsboro Turnpike Company, continuing the ferry operation (which his wife had inherited before her death), becoming involved in the effort to get the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal built, and loaning money to friends and family.(8)

In 1812 Blackford married again, this time to Elizabeth Knode. Between 1813 and 1828 they had five children, all of whom survived to adulthood, and it was during this time that Blackford pieced together Ferry Hill Plantation through multiple land purchases. Sometime around 1812, Blackford built Ferry Hill Place, an L-shaped mansion, sitting it atop a bluff overlooking the river and Shepherdstown. (Figure 2) By this time a small community, later called Bridgeport, had grown up around the ferry operation on the Maryland side of the river, just below Ferry Hill Place; most of the occupants were relatives or employees (or both) of John Blackford.

|

Figure 2. Ferry Hill Place in 2003. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Ferry Hill Plantation became a diversified farming enterprise, with the primary crops being wheat, rye, and hay. Blackford also maintained a large orchard. Blackford bought a number of slaves over the years, owning 18 at the time of his death in 1839. In addition to employing his slaves in agricultural work and as house servants, he hired a number of local free laborers, both African American and European American. These periodic employees performed a number of activities in addition to farming, including fence-mending, well construction, and timber harvesting. Rather than hiring free laborers to run the ferry, Blackford assigned two of his slaves to be "foremen of the ferry," allowing them the authority to set prices, collect money, and even hire help. At the end of each day, they would deliver the profits and receipts to Blackford.(9)

Blackford often showed concern for his slaves' physical well-being, ensuring that they were clothed properly and received medical attention when necessary. He was known to lend small amounts of money to his slaves for the purchase of personal items, and at least one of his slaves was allowed to visit his free African American wife who lived nearby. Despite this seeming beneficence toward them, Blackford's actions could be interpreted merely as concern for an investment. He did occasionally whip his slaves; he recorded several such instances in his daily journals. Unrest among the enslaved laborers was common: several of them, especially the foremen of the ferry, were frequently drunk; sometimes a slave would absent him or herself from the plantation for several days at a time; and several tried to run away on multiple occasions.(10)

Elizabeth Knode Blackford died in 1838, and throughout 1839, John Blackford suffered declining health, finally passing away in November. Upon his death, Blackford's estate was divided among his children. Franklin, the eldest son, received the Ferry Landing (Bridgeport) property, and Ferry Hill Plantation continued to operate under his guidance. In 1848, Franklin sold Ferry Hill Place and its attached agricultural land to his brother-in-law, the Reverend Robert Douglas. The ferry operation ceased in the 1850s after the Virginia and Maryland Bridge Company replaced it with the James Rumsey (or Shepherdstown) Bridge.(11)

Due to its location on the border between Maryland and Virginia, both the Union and Confederate armies occupied the Ferry Hill property multiple times during the Civil War. The most notable instance of this was during the Battle of Antietam, when Ferry Hill Place served as both a field headquarters and hospital for the Confederate Army. Robert Douglas passed away in 1867, leaving the house in the possession of his son Henry Kyd Douglas (famous author of Civil War memoir I Rode with Stonewall). The core of the old Ferry Hill Plantation ceased to be an active farm after the Civil War.(12)

Henry Kyd Douglas died in 1903, and throughout the 20th century a succession of people owned Ferry Hill Place. The house itself was expanded several times, becoming a restaurant in 1941. Many of the old outbuildings, including the slave quarters, were torn down during the first half of the 20th century, and a large Greek portico was added to the main house. In 1974, the National Park Service acquired the house along with 39 acres of surrounding property for the C&O Canal NHP. Park headquarters were set up in trailers while the previous owner continued to live in Ferry Hill Place for several years. The house was vacated in 1979, and the C&O Canal NHP moved its headquarters into Ferry Hill Place a year later, where it stayed until 2001, when the park began preparing the property for public interpretation.(13) (Figure 3)

|

Figure 3. Rear view of Ferry Hill Place, where visitors enter the house to view a historical exhibit and begin guided tours. (Courtesy of the author.) |

The Historiography of Slavery at Ferry Hill

A number of researchers have investigated the history of Ferry Hill, most of them focusing on John Blackford and his agricultural activities. Blackford's journal from January 1838 to January 1839 was published in 1961. The C&O Canal NHP commissioned a historic structure report soon after acquiring the property. In 1979 a Phase I archeological survey was conducted on the grounds surrounding the house, identifying the locations of two former structures and the 19th-century orchard. Much of the analysis was based upon oral history from the property's 20th-century owners rather than on documentary research or intensive archeological investigation, thus limiting the extent of interpretation possible. More recently, the park retained University of Maryland historian Max Grivno to write a social history of Ferry Hill Plantation, focusing on its slaves, and in 2003, I was awarded an internship to conduct further historical research on the physical layout of the plantation during the 19th century. These last two investigations, in particular, were part of an ongoing park attempt to develop a suitable public interpretation for the property, one that both adequately and accurately considers the issue of slavery at the plantation. The park also contracted with an architectural firm to prepare a cultural landscape report in 2004.(14)

During the course of my research in 2003 and 2004, I became aware of a problem with the historiography of Ferry Hill Plantation. Earlier researchers, especially Fletcher Green (editor of John Blackford's published journal), had emphasized Blackford's "beneficence" toward his slaves. While Green acknowledged that Blackford did sometimes whip his slaves, the overall picture that Green painted of him was of a kind, caring master—

Judging from the record, Blackford was a kindly, even indulgent, master. His slaves were well fed, well clothed, worked almost entirely without supervision, were given all sorts of special privileges, were given the same sort of medical care as members of their master's family, and were not severely punished. |

The problem with this interpretation is that it is poorly supported by historical evidence: As mentioned previously, Blackford records several instances in which he whipped his slaves for "misconduct," so the threat of physical punishment was, at the least, always hanging over their heads. Blackford was not above using incentives, such as the provision of alcohol, to pacify his slaves, and even Green acknowledged that the workers resisted their enslavement in various ways.(15)

While some historians of the antebellum South had begun to formulate new, more nuanced interpretations of the nature of slavery by the 1950s, many continued to follow the example of Ulrich B. Phillips, who had argued in the early 20th century that slavery was a paternalistic social order and that many slave owners actually had their slaves' best interests at heart. Phillips' interpretation continued to be the dominant paradigm until the advent of social history in the mid-1960s. Green continued to use the older interpretive model(16) which he most likely learned in graduate school.

The problem, however, is that Green's representation of Blackford has continued to inform local ideas about the nature of slavery at Ferry Hill Plantation. Green's 1961 annotation of the Blackford diaries was republished in 1975(17) and both editions are readily available in local libraries and historical archives. In addition, an interpretive panel, installed outside the house by the park in the 1970s and still standing at the time of my most recent visit in 2007, recapitulates Green's representation of John Blackford. Until 2002, when the park installed more extensive interpretive exhibits inside the house, it was the only piece of public interpretation directly available to park visitors.

A number of scholars have noted that interpretations of the past often have consequences in the present. Cultural historian George Lipsitz has recently discussed the continuing impact of inherited forms of racism in American society in the context of what he calls "the possessive investment in whiteness," or the largely hidden and ignored social and economic advantages that accrue or are denied to an individual, based on skin color. Lipsitz argues that white people often design the stories they tell about black people to escape any responsibility for pervasive racial inequality in the present: "All fiction written today by and about black people circulates in a network that includes fictions like the ones disguised as social science . . . . [This] story is a social text . . . a widely disseminated story that reinforces itself every time its basic contours are repeated [in the public sphere]."(18)

Green's interpretation of slavery at Ferry Hill Plantation is just one of a number of such social texts. It is true that not all slave owners were as vicious and violent as the fictional character Simon Legree of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and scholars have a responsibility to portray the variability and ambiguity that existed within the system of slavery. Nevertheless, the institution of chattel slavery, even in its milder forms, was fundamentally based on exploitation and the threat of physical violence. By describing the lives of John Blackford's slaves as being fairly comfortable, Green, wittingly or not, promulgated the notion that slavery wasn't that bad, which can quickly lead to the mistaken and somewhat convoluted interpretation, by less discriminating individuals, that slave owners weren't really racist, but instead their actions were allegedly undertaken in the best interests of their slaves and that therefore African Americans today do not suffer from the effects of residual racism caused by slavery.(19)

An illustration of the currency that Green's interpretation still carries locally, despite the efforts of the C&O Canal NHP, can be found in a 1997 newspaper article about Ferry Hill Place, published in Hagerstown, Maryland's Herald-Mail. Prominently placed on the front page of the Lifestyle section, the caption for its photo reads in part: "When Ferry Hill was a working plantation, guests dropped in frequently and slaves were treated like family."(20) This misleading statement appears to have been inspired by Green's introduction to John Blackford's journal.

It is indefensible to suggest that John Blackford treated his family like he treated his slaves: whipping them for disobedience, providing smaller-than-adequate living quarters, and other activities meant to demonstrate his total dominance over their lives. Slavery was a dehumanizing social institution, and the racism that was spawned by racialized slavery is still with us today in many different forms. Any attempt to excuse slavery or the conditions under which slaves had to live (no matter the supposed beneficence of their masters) is, if not inherently racist, potentially supportive of racist ideas.(21) Such excuses support that specious reasoning that, if it is possible for human beings who are owned by other human beings as chattel to be "treated like family," then slavery might not have been such a psychologically and socially devastating experience after all, much less one whose residual effects still haunt contemporary society.

Statements like those in the Herald-Mail article may merely be the product of uninformed opinions, but the incipient racism that they represent is still alarmingly widespread (although the manifestations of racism today are subtler than they were even just a few decades ago). Lipsitz has charged "both scholars and citizens . . . to avoid complicity in the erasures effected by stories that obscure actual social relations and hide their own conditions of production and distribution," especially in the context of African American history. In simpler terms, professional historians, archeologists, and site interpreters have an ethical responsibility to disabuse the public of ideas such as the notion that slaves could ever possibly have been "treated like family" by their owners.(22) John Blackford may not have been the most physically violent slave owner in the South, but like virtually all slave owners, his actions were motivated primarily by a desire to maximize profits from his investment in human chattel.

The Presentation of Slavery at Ferry Hill Plantation

The question for those who work at plantations that have been preserved as public historic sites, then, is how to identify for the public the ways in which control and exploitation were intimate and not always overtly visible parts of the everyday lives of enslaved African Americans. As mentioned previously, the C&O Canal NHP has been engaged in just such a project at Ferry Hill Place for some time.(23) Until recently, however, the site was largely closed to the public, first due to its use as park headquarters and more recently, because park staff and contractors have been conducting research and preparing appropriate interpretive materials. The property has, however, recently been opened for weekend tours.

Prior to the past few years, the only interpretive material at the site was the previously mentioned panel from the 1970s. Upon entering the house from the rear, visitors first see an installation of six panels of photographs and text summarizing Ferry Hill Plantation's history. The first panel covers the early history of the ferry operation and John Blackford's accumulation of land; the second discusses the property's inclusion in the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program for its association with slavery in western Maryland;(24) the third examines the impact of the Civil War upon the property; the fourth provides information on the house itself; and the fifth and sixth panels return to the topic of slavery. The panels that discuss slavery at the plantation utilize excerpts from the diaries of both John and Franklin Blackford to illustrate the physical punishment (whipping) that John Blackford meted out to his slaves; Franklin's participation in the capture of runaway slaves for monetary reward; and several of the enslaved laborers' various modes of resistance to slavery, including absenteeism and even abortion. In addition, the sixth panel points out to visitors that size-wise, Ferry Hill was an unusual Washington County farm, since it was large enough to support a permanent group of enslaved laborers.

After viewing the small exhibit, visitors are taken on a guided tour of the house. The tour consists primarily of descriptions of the function of each major room, including attention to the separation between "male" and "female" spaces and "master" and "servant" spaces.(25) During training, tour guides are instructed to note for visitors two aspects of John Blackford's study on the first floor: first, that it was positioned so he could survey his fields from his window (presumably so that he could keep an eye on his field hands, both enslaved and free); and second, that a direct route from the exterior to his office was constructed so that any time one of his enslaved laborers needed to see him, he or she would not have to pass through the Blackford family's living space.(26)

Another way of getting beyond Fletcher Green's flawed interpretation is to begin to look at, and present to visitors, the mechanisms of everyday social and behavioral control that were vital to the maintenance of slavery as a social and economic institution. Specifically, I propose that critical landscape analysis is a fruitful approach to the preparation and presentation of public interpretive materials at former sites of slavery. Historical landscapes are a central subject of research for American archeologists,(27) but too often these analyses are quarantined in the academic literature and do not make it into public interpretation. At former plantations, it is especially important that we begin to present the mechanisms of social control that were embedded in the local landscape.

In the remainder of this article I will suggest how we might use archeological, archival, and topographical evidence to investigate how John Blackford may have taken advantage of the natural landscape of his plantation. Specifically, I hypothesize that Blackford used the psychological technique of panoptic surveillance to discipline his enslaved workers and to prevent them from behaving in ways other than those he desired, or which hindered his maximization of profit from their labor. Without further research, little archeological data analysis is possible for Ferry Hill at this point, as only a Phase I shovel test pit survey has been conducted at the site. However, the results of the preliminary landscape analysis presented here should help to facilitate the production of an expanded archeological research design that can address the central issues of social control, exploitation, and the violence of slavery that are currently problematic in the local popular understanding of Ferry Hill Plantation's past. Such work can assist the park in its interpretive efforts.

Panoptic Theory

The concept of panopticism grew out of European philosophy concerning social control and the correction of deviance in the late 18th century. Samuel Bentham originally conceived of the panopticon in Russia while attempting to transplant English manufacturing methods there, but it was his brother Jeremy Bentham, the famous economist and social philosopher, who developed the idea to its full potential in the form of a prison (although he advocated for its use in other institutions such as schools, hospitals, and mental asylums, as well, where inspection of inmates was also a concern). The design quickly gained great popularity.(28)

The design of the panopticon is quite simple. Archeologist and critical race theorist Terrence Epperson has described the—

ideal panopticon [as] an observation tower within a large circular courtyard surrounded by an annular cellblock several stories high but only one room deep. Each cell should be occupied by only one surveillant who is subject to constant observation from the tower; yet the design of the panopticon simultaneously prevents communication between inmates. Ideally, the central tower is screened, so the inmates never know who (if anyone) is in the observatory at any particular time.(29) |

This design is intended to produce several effects. Because the inmate can never tell whether or not he or she is being watched, he or she eventually comes to feel as though under a perpetual state of observation, which "assures the automatic functioning of power." For fear of doing something disallowed and then caught, the inmate begins to monitor him or herself. This internalization of the power the inmates constantly feel from the authority's watchful gaze, in the end, catches them up "in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers." In short, the result, if the panopticon works, is that the internalization of self-discipline becomes permanent for the inmates, thereby enabling their reinsertion into society as properly functioning citizens.(30)

Despite its popularity as a concept in the early 19th century, actual instances of formal panopticons were relatively rare.(31) While the panopticon is a specific architectural design, however, panoptic surveillance can be conducted in other settings as well. Epperson, for instance, has applied panoptic theory to the plantations of Thomas Jefferson (Monticello) and George Mason (Gunston Hall) in late 18th-century Virginia. Epperson's study of Monticello and Gunston Hall illustrates how two of the United States' founding fathers used various techniques, including the design of formal gardens and the manipulation of the rules of perspective, to ensure that their enslaved laborers felt themselves to be under the watchful "eye/I" of their masters at all times, while simultaneously shielding the workers from the actual views of Mason and Jefferson.(32)

For instance, on the north side of Gunston Hall, Mason planted four rows of over 50 cherry trees each lining a carriageway and footpaths. These trees were planted in just such a way that someone standing in the middle of the doorway on this side of the mansion could only see the first tree in each row; take one step to either side, however, and all of the trees came into view. Landscapes manipulated in this way have been called "spaces of constructed visibility," but Epperson notes the need to consider also "spaces of constructed invisibility." At Gunston Hall, a row of large walnut trees shielded the slave quarters from the mansion.(33) At early Monticello, dependencies, including slave quarters, were used to frame formal gardens. However, these buildings were located at the base of a hill and could only be entered from that side, enabling Jefferson "simultaneously to preserve his view of the surrounding landscape, mask the dependencies from view, yet still incorporate them into the rigid, symmetrical space of the immediate plantation nucleus."(34)

Epperson concludes that the panoptic designs of Gunston Hall and Monticello had more to do with Lockean "possessive individualism" and erasing enslaved laborers (who were conceived of as property) from the political landscape than with actual psychological control.(35) However, James Delle, Mark Leone, and Paul Mullins have argued that this type of manipulation of the landscape was also a means of illustrating "[one] class's ability to order time and nature" and thus "[legitimized] class relations because they were intended to promote underclass deference to gentry decision-making grounded in natural law." True panopticism, which assumes "either common citizenship or common values," was not possible on plantations, since social relations between the races were structured on the basis of inequality. However, "the deliberately focused gaze of surveillance institutions acted as a modified form of panoptic discipline."(36)

I will take a slightly more orthodox approach to panopticism at Ferry Hill Plantation while still using Epperson's analysis of Monticello and Gunston Hall as a guide. From his study, three key spatial aspects of panoptic plantations can be identified: formal landscape design, viewshed (both from and back toward the point of power), and the erasure of enslaved workers from the actual view of the elite. Evidence from both primary historical documents and the historic landscape of the plantation (as revealed through architectural and archeological studies) suggests that two of these characteristics were almost certainly present at Ferry Hill during John Blackford's life, and there is circumstantial evidence that the third might have been as well.

Evidence for Panoptic Surveillance at Ferry Hill Plantation

In his now classic study The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790, Rhys Isaac argued that in the decades surrounding the Revolutionary War, southern aristocrats demonstrated their "natural" social eminence by elevating their houses above all surrounding dependencies, such as kitchens, slave quarters, and barns; thus, social inferiors (both enslaved and free laborers alike) living and working in such places literally had to look up to their masters. Indeed, architectural historian Camille Wells has written that planters' houses were "more than [places] of dwelling—[they were] the vantage from which a planter surveyed and dominated his idealized landscape . . . In almost every respect, the texture and pace of life in [the 18th century] was determined by the impulse of landowning planters to achieve, maintain, and demonstrate their authority over others."(37)

More recently, anthropologist John Michael Vlach has extended this argument into the world of plantation artwork. In a survey of plantation landscape paintings spanning the late 18th century to the end of the 19th century, Vlach notes that antebellum Southern landscape artists routinely violated one of the primary principles of contemporary landscape art in the United States by depicting the mansion houses that were their subjects from a lowly vantage point. (During the 19th century, landscape artists usually depicted the surrounding landscape from an elevated position in order to communicate human mastery over nature.) The purpose of depicting planters' houses from a depressed vantage point was to create "images as seen by an upturned face, one that implicitly signaled submission and respect." Furthermore, antebellum plantation artists frequently erased enslaved laborers from the landscape altogether; they focused the paintings on the mansion house instead, rather than the fields or other areas where daily labor took place. The planters and their families were depicted as people of leisure, rather than labor: All that they had was theirs because of their natural superiority, not hard work or a privileged background.(38) As a socially connected middling planter, Blackford would have been well aware of these symbolic manipulations of the landscape.

In line with the importance of vantage in 18th- and early 19th-century Chesapeake plantations, perhaps the most important panoptic aspect of Ferry Hill Plantation was its viewshed from Ferry Hill Place, where Blackford lived and worked. He very rarely performed any physical labor himself, instead spending most of his days in his study or directing and inspecting the work of others.(39) As mentioned earlier, however, Ferry Hill Place was situated on top of a bluff overlooking the Potomac River and Shepherdstown. Given the plantation's location nestled in a horseshoe bend of the Potomac, Blackford had a direct view of large portions of his plantation from his home. In addition, he had a very good view of Bridgeport and the ferry operation. Thus, from various points in his mansion John Blackford could have kept watch over all of his workers, both enslaved and hired. (Figure 4)

|

Figure 4. View of Ferry Hill Plantation and Bridgeport from Shepherdstown after a flood in 1924. This photograph provides a particularly good illustration of the viewshed from Ferry Hill Place (upper left corner). (Courtesy of the Historic Shepherdstown Museum.) |

But could the enslaved laborers at Ferry Hill, and especially the "foremen of the ferry," see whether or not Blackford was watching them? The travel memoirs of Anne Royall, a visitor to Ferry Hill Place in the late 1820s, suggest they could not. She described her journey across the river from Shepherdstown thus—

Seeing a beautiful mansion perched on the summit of a lofty eminence, on the opposite shore, I was told it was [Ferry Hill Place], and wishing to take a near view of the site, I left my baggage to come with the stage, and crossed the river. After a pretty fatiguing walk up a moderate mount, I found myself on a level plain . . . the view from it [Ferry Hill Place] is equally grand. But the house appears to more advantage when viewed from the Virginia shore. . . . [John Blackford] was sitting in his cool portico, which overlooks the whole country, and was watching me, he said, from the time I left Shepherdstown.(40) |

Royall did not notice Blackford himself until she arrived at the mansion. Thus, it would seem that Blackford could keep an eye on ferry operations, without the enslaved workers responsible for operating the ferry knowing it. Such insecurity would have been meant to provide the impetus for the internalization of gaze and therefore self-discipline, that was crucial to the success of panoptic surveillance.(41)

The second aspect of panoptic plantations is formal landscape design. In late 18th-century "power gardens" such as those at Gunston Hall, Monticello, and William Paca's garden in Annapolis, Maryland, designers used terracing and the careful placement of shrubbery or trees to manipulate vision and perspective.(42) These designed landscapes served to illustrate and naturalize the power of the social elite. Neither John Blackford nor his eldest son Franklin ever made mention in their journals of a formal garden or of ornamental landscaping, as was the norm in "power gardens." Once again, however, John Blackford's education and passion for knowledge suggest that he would have been familiar with the literature on ornamental garden design, at least in passing.

In addition, other primary sources hint at the existence of formal landscaping at Ferry Hill Place. One such piece of evidence comes again from Anne Royall's description of her visit to the estate: "[Ferry Hill] lacks nothing to render it a paradise; it is well built, of brick, and magnificently finished; the terraces, network, gardens, and shrubbery all correspond." A second clue comes from Blackford's March 23, 1830 journal entry, when he noted that he was having mulberry trees planted on the lawn. Both white and black mulberry trees were often used in ornamental gardens. Finally, an advertisement, placed in a Hagerstown newspaper just a week after the above-mentioned 1830 journal entry, provides a detailed description of the plantation. Concerning the house's lawn, Blackford parsimoniously wrote that it "consist[ed] of about five acres, [and was] adorned with a variety of fruit and ornamental trees." He makes no mention of any slave quarters.(43 )

Evidence from archeology, oral history and the historical record all suggest that the slave quarters were obscured from the direct view of Ferry Hill Place, indicating the visual erasure of enslaved laborers from the landscape: the final important characteristic of panoptic plantations. During the 1979 archeological survey, the field crew uncovered evidence of two buildings to the rear of the mansion house. A former tenant at Ferry Hill Place in the early 20th century with ties to Blackford's descendants identified one of these buildings as a three-room service building. While the archeological survey uncovered no conclusive evidence of the slave quarters, the same tenant described the placement of the quarters to the north of the service building, or what would have been behind it from the vantage point of Ferry Hill Place.(44) Thus, the quarters where the enslaved laborers actually lived would have been shielded from the view of the Blackford family and their visitors. It remains for archeology to verify the service building's age because it is possible that the structure was constructed some time after John Blackford's death in 1839. The following section further discusses archeological research needed to discover evidence about panoptic surveillance.

Evidence for the Success of Panoptic Surveillance at Ferry Hill

Jeremy Bentham originally intended panopticism to be used to inculcate habits of self-discipline in people under surveillance, a use which presupposes the existence of individuals who understand themselves to be such and who are capable of holding certain social values and an aptitude for citizenship. However, Marcus Wood has argued that "the majority of [physical and psychological] torture inflicted on slaves grew out of the desire to break down the personality of the subject/victim, to generate and then enforce a consciousness of disempowerment and anti-personality."(45)

In his study of coffee plantations in Jamaica, for instance, James Delle skillfully analyzed the spatial strategies used by white plantation owners during the pre-emancipation period in that country (then a British colony) in attempts to control the behavior of their enslaved workers. Within individual plantations, he identified a number of activity spheres that were kept spatially separate. Domestic space was further segregated by race and class: the white owner's great house, the white overseer's house, and African Jamaican slave villages. Agricultural spaces of production were further segregated into elite commodity production (coffee fields) and provision grounds for both subsistence and commodity production by enslaved laborers. Industrial space included coffee milling complexes and intermediate spaces were areas that were undeveloped and unused.

Although planters kept these spaces separate, the social hierarchy of the plantation was represented in their spatial layout as well as their material characteristics. Domestic spaces, for instance, were clearly distinguishable: the "great house" of the plantation owner was, not surprisingly, the largest, followed by the overseer's house and then slave houses. Great houses could be isolated from other areas of the plantation, but often they were situated within view of the industrial spaces of production. Overseer's houses were placed either within or adjacent to these same spaces. These placements were useful because they allowed the overseers, and sometimes the owners, the opportunity for perpetual surveillance of the industrial production process—and also, therefore, the labor of the enslaved workers.(46)

Furthermore, the location of slave villages and the materials with which slave huts were constructed attest to their devaluation. Slave villages were often clustered in areas of a plantation that were considered to be marginal to the coffee production process. The small huts in which enslaved laborers lived were made of perishable materials (unlike the great houses and overseers' quarters, which were built of stone or strong timber), and thus would have needed repairs more frequently. Another indignity was the cartographic practice of either vaguely referring to an area as the "Negro grounds," or leaving any mention of slave quarters off of plantation maps altogether.(47) To control the laboring population, owners and overseers also restricted slaves' movement within the plantation and kept the work process under perpetual surveillance. In these ways, the planter elite conceptually devalued the labor of the enslaved population, as well as the laborers' personal dignity as human beings.(48)

How could these two seemingly conflicting goals—on one hand, to inculcate self-discipline based on a shared set of values and expectations, and on the other, to obliterate the subject in order to create an anti-personality—coexist and function on slave plantations? The differing contexts of the European and Euro-American rehabilitative or educational institutions (for instance, prisons, poor houses, mental asylums, or schools) and the American plantation are of paramount importance. In the former context, the goal of discipline was to create individuals capable of functioning in society according to specific, predetermined rules of behavior and even thought. The latter context, however, operated on the assumption that Africans and African Americans were biologically and mentally incapable of such assimilation. Any challenge to this assumption, such as insubordination by enslaved laborers (taking any form, from armed rebellion to the acquisition of literacy), had to be obliterated. The psychological torture of panoptic surveillance, intended in this context to break down the individual subject and to create an "anti-personality," was therefore perfectly consistent with the prevailing racial ideology and in fact accomplished the same ultimate goal (the validation and naturalization of the social order) as it did in its original institutional context.

The evidence from the historical record seems to indicate that at Ferry Hill, as at most sites of enslavement (including the Jamaican coffee plantations analyzed by Delle), John Blackford did not achieve this goal through surveillance of his enslaved workers. Delle, Leone, and Mullins have characterized the relationship between masters and slaves on plantations as "the dialectics of discipline and resistance."(49) There is plenty of evidence that Ferry Hill Plantation's slaves actively resisted discipline, including accounts of runaways (all of whom were caught), prolonged periods of absenteeism, frequent drunkenness, and even an abortion.(50) Such resistance seems to indicate that individualism did indeed exist among the enslaved laborers, and that Blackford was unable to instill self-discipline (or the absence of resistance) and overwhelming feelings of disempowerment in his slaves.

Given the ambiguities of the historical record on the relationship between discipline and disempowerment at the plantation, further archeological investigation at Ferry Hill could help address questions as to the extent and effectiveness of surveillance techniques used at the plantation. The archeological survey completed in 1979 was only preliminary and was conducted before plantation archeology emerged as a major field of study within historical archeology. Even today, very few archeological studies of plantation life have dealt with small, agriculturally diverse sites such as were common in the piedmont of Maryland and Virginia.(51) Phase III excavations should be undertaken around the house and in the vicinity of the possible slave quarters to find any evidence relevant to surveillance, control, and resistance at Ferry Hill Plantation.

The first step should be to more accurately date the "service building" (or any predecessors upon whose foundations it may have been constructed), as well as to firmly locate and excavate the slave quarters. This would allow researchers to create a better reconstruction of the antebellum landscape of the plantation than is currently possible, and might be able to support or refute the hypothesis that the slave quarters were hidden from view behind the service building—an example of constructed invisibility.

Another line of analysis should focus on ceramic assemblages from any privies, trash dumps, or other features that might be found. What kinds of ceramics did the enslaved laborers use? Did they make their own ceramic vessels, or did they participate in a local or even regional trade network with other slaves or free black people? Or, did they receive hand-downs from the Blackford family? Standardized assemblages have been shown to indicate conformity to a predefined order;(52) if the Blackfords' slaves attempted to piece together matched sets of dishes, this may be an indication that they used material culture to resist the antebellum plantation's dehumanizing discipline by laying claim to an equality that they were denied as slaves. On the other hand, if ceramics can indicate the success, or lack thereof, of the disciplinary process, then material assemblages associated with the Blackford family might be able to indicate the opposite process, that of the establishment of an ideology of natural hierarchy.

Fine-grained stratigraphic interpretation coupled with detailed pollen analysis and the location of planting features in the yard areas immediately surrounding the mansion might be able to answer securely whether ornamental landscaping ever existed on the grounds of Ferry Hill Place.(53) Did commonly used ornamental landscape plants, such as mulberry trees, exist at Ferry Hill prior to the Civil War? Can the archeological traces of such planting episodes reveal information about the spatial organization and density of any ornamental gardens that may once have existed? Again, the answers to such questions could help park staff to test hypotheses of the plantation's constructed visibility and invisibility.

Finally, understanding the Bridgeport landscape (the location of the ferry operation) would provide yet more evidence for questions of the estate's constructed visibility and invisibility. Bridgeport has been damaged by periodic floods and, more recently, bridge construction and repair. These post-depositional events may have severely impaired or even destroyed this portion of Ferry Hill Plantation's archeological potential. Testing should be conducted in the Bridgeport area to determine the feasibility of further archeological study there. Archeological investigation of intact areas could address the following questions. For instance, how large an area did the foremen of the ferry have to move around in, and were any parts of this area out of sight of the mansion house? Or were there other possibilities for escaping from Blackford's surveillance, such as buildings to hide in or behind? Are there material remains of the ferry foremen's activities, such as drinking, that would provide evidence that surveillance to instill an appropriate subjectivity (or anti-personality) in them failed?

Conclusion

While there is no indisputable evidence for the use of panopticism at Ferry Hill, the balance of archival and archeological evidence points toward that conclusion and highlights the need for additional research. The argument put forth here is intended to defuse the idea that slavery as experienced at Ferry Hill Plantation was fairly comfortable, but it represents only a first step. The C&O Canal NHP has been steadily working toward a new public interpretation of the property that fully accounts for the lived realities of slavery. Ferry Hill Place is a local landmark familiar to many Washington County history buffs, and it will not be easy to modify longstanding beliefs about John Blackford and his treatment of enslaved laborers. Archeology and critical landscape analysis, however, are two tools that could greatly aid in the development of a nuanced yet compelling interpretation of the enslaved African Americans' daily lives at Ferry Hill.

About the Author

Robert C. Chidester is a candidate in the Doctoral Program in Anthropology and History at the University of Michigan and co-director of the Hampden Community Archaeology Project in Baltimore, Maryland. The research on which this article is based was conducted during an internship with the C&O Canal National Historical Park and funded by Partners in Parks in 2003-2004.

Notes

1. An earlier version of this article was presented at the 34th Annual Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, in 2004. I would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance during the writing and preparation of this article: James Perry and the staff of C&O Canal NHP in Hagerstown were extremely helpful and supportive during my internship. Mark Leone and Douglas Sanford read and commented on the MAAC conference paper. Bill Justice and Curt Gaul from NPS and two anonymous CRM reviewers provided insightful comments on earlier drafts of the present article. Jason Shellenhamer and Meghann Kent provided me with useful supplementary information on power gardens and tours of Ferry Hill Place, respectively. Finally, Martin Perschler and Barbara Little have been most helpful in shepherding this article through the review and publication process.

2. See Laura (Soullière) Gates, "Frankly, Scarlett, We Do Give a Damn: The Making of a New National Park," George Wright Forum 19(4)(2002): 32-43; Michèle Gates Moresi, "Presenting Race and Slavery at Historic Sites," CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship 1(2)(2004): 92-94; Sharon Ann Holt, "Questioning the Answers: Modernizing Public History to Serve the Citizens," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 129(4)(2005): 473-481; James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, eds., Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory (New York: The New Press, 2006); essays by Carol McDavid, Lori Stahlgren and Jay Stottman, and Kelly Britt in Barbara J. Little and Paul A. Shackel, eds., Archaeology as a Tool of Civic Engagement (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2007); Carol McDavid, "Descendants, Decisions, and Power: The Public Interpretation of the Archaeology of the Levi Jordan Plantation," Historical Archaeology 31(3)(1997): 114-131; Parker B. Potter Jr., "What Is the Use of Plantation Archaeology?" Historical Archaeology 25(3)(1991): 94-107; John Tucker, "Interpreting Slavery and Civil Rights at Fort Sumter National Monument," George Wright Forum 19(4)(2002): 15-31.

3. While the property has historically been called a plantation by both researchers and local residents, this is a somewhat misleading description. The largest number of slaves that Blackford is known to have owned at any one time is 18, two shy of the number usually required for plantation status (at least in the Deep South; see Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South [New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1956], 30). Instead of a large workforce of enslaved laborers, Blackford utilized a mixed labor force of his own slaves, enslaved African Americans whose labor he hired from other slave owners, and both white and black free laborers.

4. Fletcher M. Green, ed., "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal, January 4, 1838-January 15, 1839," The James Sprunt Studies in History and Political Science 43 (1961): xviii-xix; Max L. Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey: Ferry Hill Plantation, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historic Park" (unpublished report, C&O Canal National Historical Park, Sharpsburg, MD, 2001), 50. On the history of the "Lost Cause" movement, see David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2001).

5. The practice of slavery in Western Maryland has a long history of being described as "the mildest form of slavery," stretching back even to the antebellum period. See Edie Wallace, "Reclaiming the Forgotten History and Cultural Landscapes of African-Americans in Rural Washington County, Maryland," Material Culture 39(1)(2007): 11-12.

6. Potter, "What Is the Use," 103.

7. Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 17-18.

8. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," xiii; Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 19-21; Hagerstown Guardian, September 22, 1812, 3.

9. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," viii, xii, xv-xvi; Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 17-18, 40, 42; Hagerstown Torch Light and Public Advertiser [HTLPA], April 1, 1830, 3.

10. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," xviii-xix; Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 41, 48-49; Harry Warner, "The Life of Slaves at Blackford's Ferry Hill Plantation," Daily Mail, Hagerstown, Maryland, October 27, 1982, A-9.

11. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," xiii, 96; Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 55-56; Deed from Blackford to Douglas, November 11, 1848, Washington County Land Records, Deeds, Liber IN3 Folio 816, Maryland State Archives [MSA]; Melissa Robinson, "Ferry Hill Place Resource Guide" (unpublished report, C&O Canal NHP, Sharpsburg, MD, 1998), 16.

12. Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 56, 61-66. Henry Kyd Douglas's memoir (I Rode with Stonewall, Being Chiefly the War Experiences of the Youngest Member of Jackson's Staff from the John Brown Raid to the Hanging of Mrs. Surratt [Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1940]), a classic of "Lost Cause" propaganda, may have been the original inspiration for the historical narrative of paternalistic, comfortable slavery at Ferry Hill Plantation.

13. C&O Canal NHP, Ferry Hill Place (Hagerstown, MD, n.d.); Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 71, 75; Barry Mackintosh, C&O Canal: The Making of a Park (Washington, D.C.: History Division, National Park Service, 1991), 141-142; Robin D. Ziek, Archeological Survey at Ferry Hill (Denver: Denver Service Center Branch of Historic Preservation, National Capital Team, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, 1979), 7-8.

14. Robert C. Chidester, "Final Report on Historical Research, Ferry Hill Plantation, C&O Canal National Historical Park" (unpublished report, Partners in Parks, Paonia, CO and C&O Canal NHP, Hagerstown, MD, 2004); Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal;" Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey;" Quinn Evans Architects, "Cultural Landscape Report: Ferry Hill" (unpublished report, C&O Canal NHP, Hagerstown, MD, 2004); Harlan Unrau, "Historic Structure Report: Ferry Hill Place" (unpublished report, C&O Canal National Historical Park, Sharpsburg, MD, 1977); Ziek, Archeological Survey.

15. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," xix-xx.

16. Ulrich B. Phillips, Life and Labor in the Old South (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1929). On the development and growth of social history in the United States, see Geoff Eley, A Crooked Line: From Cultural History to the History of Society (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005); and Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The "Objectivity Question" and the American Historical Profession (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 440-445. Two of the most influential early examples of the new social history interpretation of slavery are Stanley M. Elkins, Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1959) and Stampp, The Peculiar Institution.

17. Fletcher M. Green, Thomas F. Hahn, and Natalie W. Hahn, eds., Ferry Hill Plantation Journal: Life on the Potomac River and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, 4 January 1838-15 January 1839 (Shepherdstown, WV: American Canal and Transportation Center, 1975).

18. George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Benefit from Identity Politics, rev. ed. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 177. For more on the forms and impacts of inherited (and largely invisible) forms of racism in American culture, see Barbara J. Fields, "Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the United States of America," New Left Review 181(1990): 95-118; and Potter, "What Is the Use."

19. See Potter, "What Is the Use," 103.

20. Pat Schooley, "Ferry Hill," Herald-Mail, Hagerstown, Maryland, March 2, 1997, D1, D4. Hagerstown is the seat of Washington County and the nearest city to Ferry Hill Place.

21. Fields, "Slavery, Race, and Ideology;" Potter, "What Is the Use."

22. Terrence W. Epperson, "Race and the Disciplines of the Plantation," Historical Archaeology 24(4) (1990): 35; Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, 177; Potter, "What Is the Use."

23. See Chidester, "Final Report," and Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey." The park did not contribute to the original publication of John Blackford's journals in 1961, their republication in 1975, or the production of the 1997 Herald-Mail article.

24. Ferry Hill Place was added to the Network, which is a project of the National Park Service, in 2002 (see National Park Service, "Network to Freedom Database: Ferry Hill Plantation" [2001]; electronic document available online at http://home.nps.gov/ugrr/TEMPLATE/FrontEnd/Site3.CFM?SiteTerritoryID=168&ElementID=156).

25. These descriptors are my own, and not the tour guides'.

26. Meghann Kent, C&O Canal NHP Intern, personal communication, June 16, 2007.

27. For examples of some of the most influential landscape studies within American historical archeology, see the following: James A. Delle, An Archaeology of Social Space: Analyzing Coffee Plantations in Jamaica's Blue Mountains (New York: Plenum Press, 1998); William M. Kelso and Rachel Most, eds., Earth Patterns: Essays in Landscape Archaeology (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1990); Mark P. Leone, "Interpreting Ideology in Historical Archaeology: Using the Rules of Perspective in the William Paca Garden in Annapolis, Maryland," in Ideology, Representation and Power in Prehistory, ed. Christopher Tilley and Daniel Miller, (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 25-35; Leone, "Rule by Ostentation: The Relationship Between Space and Sight in Eighteenth-Century Landscape Architecture in the Chesapeake Region of Maryland," in Method and Theory for Activity Area Research: An Ethnoarchaeological Approach, ed. Susan Kent (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987) , 604-633; Karen Bescherer Metheny, From the Miners' Doublehouse: Archaeology and Landscape in a Pennsylvania Coal Company Town (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006); Stephen A. Mrozowski, The Archaeology of Class in Urban America (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2006); and Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny, eds., Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996).

28. Terrence W. Epperson, "Panoptic Plantations: The Garden Sights of Thomas Jefferson and George Mason," in Lines That Divide: Historical Archaeologies of Race, Class, and Gender, ed. James A. Delle, Stephen A. Mrozowski and Robert Paynter (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 58; Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 200-206. For the original postulation of the theory, see Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon; or, the Inspection House (London: T. Payne, 1791).

29. Epperson, "Panoptic Plantations," 58-59.

30. Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 201, 203-204.

31. Epperson, "Panoptic Plantations," 59.

32. Ibid., 58-77. Epperson's use of panopticism to explain power relations on plantations is an extension of the archaeological trend, begun in the late 1980s, to replace the concepts of status and caste in plantation studies with power and class (Theresa A. Singleton, "The Archaeology of the Plantation South: A Review of Approaches and Goals," Historical Archaeology 24(4)(1990): 73). For examples, see Epperson, "Race and the Disciplines of the Plantation;" Epperson, "Constructing Difference: The Social and Spatial Order of the Chesapeake Plantation," in "I, Too, Am America": Archaeological Studies of African-American Life, ed. Theresa A. Singleton (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), 159-172; Jean E. Howson, "Social Relations and Material Culture: A Critique of the Archaeology of Plantation Slavery," Historical Archaeology 24(4)(1990): 78-91; J.W. Joseph, "White Columns and Black Hands: Class and Classification in the Plantation Ideology of the Georgia and South Carolina Low Country," Historical Archaeology 27(3)(1993): 57-73; Charles E. Orser Jr., "Plantation Status and Consumer Choice: A Materialist Framework for Historical Archaeology," in Consumer Choice in Historical Archaeology, ed. Suzanne M. Spencer-Wood (New York: Plenum Press, 1987) , 121-137; Orser, "The Archaeological Analysis of Plantation Society: Replacing Status and Caste with Economics and Power," American Antiquity 53 (1988): 735-751; Orser, "Toward a Theory of Power for Historical Archaeology: Plantations and Space," in The Recovery of Meaning: Historical Archaeology in the Eastern United States, ed. Mark P. Leone and Parker B. Potter Jr. (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988), 314-343; and Brian W. Thomas, "Power and Community: The Archaeology of Slavery at the Hermitage Plantation," American Antiquity 63 (1998): 531-551.

33. Epperson, "Panoptic Plantations," 62, 64. The phrase "spaces of constructed visibility" is from John Rajchman, "Foucault's Art of Seeing," October 44 (1988): 103.

34. Epperson, "Panoptic Plantations," 68.

35. Ibid., 72-73.

36. James A. Delle, Mark P. Leone, and Paul R. Mullins, "Archaeology of the Modern State: European Colonialism," in Companion Encyclopedia of Archaeology, Vol. 2, ed. Graeme Barker (London: Routledge, 1999), 1118-1119.

37. Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982); Camille Wells, "The Planter's Prospect: Houses, Outbuildings, and Rural Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia," Winterthur Portfolio 28(1)(1993): 28. See also Leone, "Rule by Ostentation;" and Dell Upton, "Imagining the Early Virginia Landscape," in Kelso and Most, Earth Patterns, 71-86.

38. John Michael Vlach, The Planter's Prospect: Privilege and Slavery in Plantation Paintings (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002). The quote is from page 1.

40. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," xv.

41. Anne Royall, Black Book; or, a Continuation of Travels in the United States, Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: Printed by the author, 1828), 294-295, quoted in Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 23.

42. Michel Foucault, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 (New York: Pantheon, 1980), 155.

43 .See Leone, "Rule by Ostentation;" and Carmen A. Weber, Elizabeth Anderson Comer, Louise E. Akerson, and Gary Norman, "Mount Clare: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Restoration of a Georgian Landscape," in Kelso and Most, Earth Patterns, 135-152.

44. Royall, Black Book, 294-295, quoted in Grivno, "Historic Resources Survey," 23; John Blackford, diary, 1829-1831, Manuscript 1087, Manuscripts Department, Maryland Historical Society Library; HTLPA, April 1, 1830, 3. (Why Blackford initially wanted to sell the plantation in 1830, and why he apparently decided not to do so, has never been discovered. He makes no mention of any such plans in his journal around the time of the advertisement.) I am indebted to Jason Shellenhamer (University of Maryland, personal communication, January 20, 2004) for informing me about the prevalence of mulberry trees in ornamental gardens.

45. Ziek, Archeological Survey, 25.

46. Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780-1865 (New York: Routledge, 2000), 216.

47. Delle, An Archaeology of Social Space, 120, 135-143.

48. Compare this practice to John Blackford's previously discussed omission of any mention of Ferry Hill Plantation's slave quarters in his 1830 sale advertisement, despite the fact that several other outbuildings were described in detail.

49. Delle, An Archaeology of Social Space, 143-144, 156-161.

50. Delle, Leone, and Mullins, "Archaeology of the Modern State," 1119.

51. Green, "Ferry Hill Plantation Journal," xix, 25-26.

52. However, for an example of such a study, see Kathleen A. Parker and Jacqueline L. Hernigle, Portici: Portrait of a Middling Plantation in Piedmont Virginia, Occasional Report 3 (Washington, DC: Regional Archeology Program, National Capital Region, National Park Service, 1990). An overview of the topic is provided by Douglas W. Sanford, "The Archaeology of Plantation Slavery in Piedmont Virginia: Context and Process," in Historical Archaeology of the Chesapeake, ed. Paul A. Shackel and Barbara J. Little (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 115-130.

53. Delle, Leone, and Mullins, "Archaeology of the Modern State," 1147; see also Paul A. Shackel, Personal Discipline and Material Culture: An Archaeology of Annapolis, Maryland, 1695-1870 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1993).

54. For examples of pollen and phytolith analyses as a tool in historical archeology, see Gerald K. Kelso, "Pollen-Record Formation Processes, Interdisciplinary Archaeology, and Land Use by Mill Workers and Managers: The Boott Mills Corporation, Lowell, Massachusetts, 1836-1942," Historical Archaeology 27(1)(1993): 70-94; Gerald K. Kelso and Mary C. Beaudry, "Pollen Analysis and Urban Land Use: The Environs of Scottow's Dock in 17th, 18th, and Early 19th Century Boston," Historical Archaeology 24(1)(1990): 61-81; essays by Michael Hammond, Naomi F. Miller et al., Irwin Rovner, and James Schoenwetter in Kelso and Most, Earth Patterns; and Rovner, "Floral History by the Back Door: A Test of Phytolith Analysis in Residential Yards at Harpers Ferry," Historical Archaeology 28(4)(1994): 37-48.