Article

Authenticity and the Post-Conflict Reconstruction of Historic Sites(1)

by Robert Garland Thomson

Introduction

Responses to the damage or destruction of historically significant buildings and sites as a result of armed conflict vary greatly, from precise reconstruction to memorialization of building fragments to a tabula rasa approach. Examples from around the world immediately spring to mind: Dresden's 18th-century Frauenkirche, razed by Allied bombing in 1945 yet painstakingly reconstructed in 2006; Hiroshima's Atomic Bomb Dome, a 1915 exhibition hall destroyed by the U.S. atomic warhead detonated above the city in 1945 and today preserved as a ruin; Rotterdam's medieval city center, erased by the German Blitz in 1940 and reconceived in an entirely modernist vocabulary beginning in 1946.(Figure 1) However, with the "new" histories taken on by buildings impacted by conflict come adjusted expectations for the degree of authenticity that the reconstructions will convey. These "revised authenticities" strongly influence the interpretation of post-conflict sites, often with far-reaching implications for significance and commemoration within their communities. These conditions present a distinct challenge to—and important role for—cultural resource stewards in helping communities navigate decisions related to conflict-impacted historic architecture.

|

Figure 1. Destroyed during World War II, the Atomic Bomb Dome (Genbaku Dome, formerly an exhibition hall) in Hiroshima, Japan, is preserved as a ruin. (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.) |

In a 1998 position paper for ICCROM, Jukka Jokilehto, the noted Finnish preservation scholar and theoretician, distilled a three-part framework for historic authenticity based on the 1994 Nara Document on Authenticity. These three factors, which he describes as "tests of authenticity" for historic architecture, include genuine quality of human creativity, true representation of cultural tradition or representative type, and verifiable association with an interchange of values or association of ideas.(2) While sufficiently broad so as to include a variety of heritage types, the framework does not account for revised material and narrative authenticity issues that arise in a post-conflict environment, where a site's "antiquity value" might be lost or connections to original intent altered. This void calls for an expanded set of definitions for authenticity in a post-conflict setting, where reconstruction plans and stakeholder requirements for commemoration, revival, and continuity typically extend beyond the above tests.

This paper explores three examples that demonstrate this range of post-conflict responses: the Stari Most (Old Bridge) in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina; the World Trade Center site in New York City; and the Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche (Memorial Church) in Berlin, Germany. Each site's constituent community chose to respond to the destruction or damage of their culturally significant building in vastly different ways, raising challenging questions as to the "revised authenticity" of the present-day sites. As these discrepancies illustrate, any post-conflict reconstruction plan demands an informed discussion among various stakeholders within a community regarding the desired type of authenticity, accompanied by a robust understanding of the implications of each approach.

In order to provide guidelines for future discussion, this paper proposes three new categories of authenticity that may be applied to post-conflict sites. These categories should serve to better equip cultural resource professionals in their efforts to work with communities in determining the most appropriate treatments for conflict-impacted historic structures. Similarly, these new categories will ideally lead to the development of a more sophisticated framework for discussing other "revised authenticities" that might result from natural disaster or contextual changes, in addition to post-conflict sites.

Authenticity in the Post-Conflict Environment

For better or worse, conflict has always comprised part of the human experience. Because the impulse to build is similarly ingrained, the two phenomena have invariably intersected throughout history, resulting in countless examples of glorious architectural achievements reduced to rubble. Despite the timelessness of this dynamic, the combination of today's diverse built environment with new professional disciplines charged with interpreting, classifying, and preserving it have resulted in ever-more sophisticated responses to the destruction of culturally significant architecture. Furthermore, the 20th century—widely regarded as the most productive and most destructive period of human history thus far—offers innumerable examples of community response to injuries inflicted upon the built environment.

In nearly all cases, post-war recovery involves extensive reconstruction either out of pragmatic necessity, defiance against aggressors, or maintenance of continuity with a pre-conflict time. For example, following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack on the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, construction schedules were accelerated in order to restore the building fully before the one-year anniversary as an act of defiant, patriotic resolve.(3) The degree of post-conflict reconstruction executed also varies widely and often takes place without regard to the integrity of original materials or, in the event of a tabula rasa approach, can involve the negation of a pre-conflict structure altogether. Take, for example, the 19th-century teakwood Royal Palace in Mandalay, Myanmar (Burma), which burned during fighting between British and Japanese forces in 1945, only to be rebuilt in concrete and corrugated iron by the national government. Both of these approaches stand at odds with the traditional, narrowly defined Western concept of "authenticity," which emphasizes material originality and a direct association with an author or particular time of origin, thus eschewing replicas, reproductions, and copies.(4)

As the field of historic preservation has become global in scope, however, this rigid concept of authenticity has come under intense scrutiny. The Nara Document on Authenticity in particular calls into question the Western-centric emphasis on material authenticity, stressing the variability of authenticity values between (or even within) cultures. According to Nara, authenticity "may include form and design, materials and substance, use and function, traditions and techniques, location and setting, and spirit and feeling, and other internal and external factors."(5) By delineating such an expansive spectrum of values, the 1994 document permits the recognition of historic significance according to a range of factors beyond pure material or age-related authenticity, thus potentially validating actions such as reconstruction following a conflict episode.

As the field of historic preservation has become global in scope, however, this rigid concept of authenticity has come under intense scrutiny. The Nara Document on Authenticity in particular calls into question the Western-centric emphasis on material authenticity, stressing the variability of authenticity values between (or even within) cultures.

Other theoreticians within the field of historic preservation have teased out the implications of the Nara Document's variable take on authenticity, in some cases highlighting how acceptable levels of authenticity can shift over time depending on events, community needs, or collective memory. Cesare Brandi, the esteemed Italian architect and historic preservationist, has acknowledged that the history of an artwork (including buildings) bears as much on that work's definition as its creation. Including factors external to a building's origins—such as alterations and wear—logically expands its definition beyond that of its creators' initial intentions.(6) Building on Brandi's cumulative understanding of how an object's experience through time impacts its meaning, Greek architectural historian Vasiliki Kynourgiopoulou notes how the collective memory of constituent communities plays a significant role in ascribing authenticity determinations. She goes on to point out that the authenticity of a particular object is contingent upon the context and time in which it was created, in addition to the particular need it has come to satisfy within a community.(7) Eman Assi, a Palestinian historic preservationist, further emphasizes this community-focused, variable view of authenticity based on her extensive work in Jerusalem. She observes that authenticity determinations constitute a community action forged through collaboration and compromise with professionals rather than a domain controlled solely by those professionals.(8)

Collectively, these opinions shed considerable light on the issue of authenticity in the context of a post-conflict environment. Episodes of conflict (among other things, of course) contribute to the histories of buildings, often in dramatic or catastrophic ways that can permanently alter—or even destroy—their material integrity. Although these episodes certainly compromise a building's originality and connection to a particular time or author, they can also imbue the structure with a new meaning or even enhance its previous significance. Community responses to conflict episodes take into account these shifts, and reconstructions therefore reflect collaborative community needs, rather than strict professional requirements. As a result, buildings reconstructed following conflict can contain authentic elements of the original structures (even if only in memory), in addition to an authenticity newly bestowed upon them by their constituents.

Paolo Marconi, the Italian restoration architect and academic, has noted in his writings that community-driven reconstruction decisions can produce multifarious results. These range from creating beacons of painful memory or celebrated defiance, or even encouraging a "ceremony of repression" of traumatic events, particularly in the event of complete reconstruction. Marconi calls upon historic preservationists to help translate community needs into appropriate reconstructions while helping to avoid inauthentic production of pastiche that can arise from ill-conceived interventions.(9)

Navigating the turbulent waters of constituent-based mediation and assignment of meaning has more frequently been the domain of anthropologists and ethnologists than of preservationists. Social scientists have even accused the field of historic preservation of disrupting the process of "place attachment," which involves communities' assignment of new meaning to a site over time, even when those communities are culturally or historically unattached to the "place" in question.(10) However, historic preservationists more than most understand "place" as a powerful retainer of historic authenticity.(11) Similarly, they frequently deal with individual sites that carry multiple layers of history and meaning and in most cases are specifically charged with preserving and interpreting them in sum. As proof, one need look no further than the fourth of the U.S. Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, which states that "changes that have acquired historic significance in their own right shall be retained and preserved."(12) Most examples of post-conflict reconstruction are multivalent in precisely this way, with a conflict episode itself bestowing new historic significance upon an already meaningful place.

The challenge for cultural resource stewards in facilitating community discussions related to post-conflict reconstruction lies not in skill sets or unfamiliarity with the relevant concepts, but in the complexity of the dialogues themselves. As the already-cited examples of reconstruction solutions demonstrate, treatment of these sites can be multi-layered, containing elements of old and new, revival and commemoration, side by side. Authenticity may be directly conveyed by the relationships between new and old, or between built structures and hollow voids. Furthermore, discussions around particular approaches frequently change dramatically over time, resulting in a solution that speaks to the social, political, or economic conditions of a specific era more than a clear consensus.

The previously mentioned Dresden Frauenkirche provides a particularly apt example of the shifting community dialogues that can accompany reconstructions. Destroyed in February 1945, the church was rebuilt in full by 2006 following a spirited nationwide debate.(Figures 2-3) For decades, the monumental structure sat as a pile of rubble, an implicit reminder to the residents of then-Communist East Germany of the Nazi era's horrendous folly. Not until after German re-unification in 1990 did the dialogue shift toward reconstructing the Frauenkirche—an idea opposed by many, including many in the German historic preservation community. Framed as a new nationalist effort for the freshly united country, the effort ultimately overcame its critics (not to mention the considerable engineering challenges associated with reconstruction), and in 2006 the new church re-opened concurrent with the 800th anniversary of Dresden's founding. What had once served as a poignant, painful reminder of a difficult time had, according to its supporters, become a new symbol of Germany's recovery.(13) Ultimately, the community dialogue and political climate that led to the reconstruction of the Frauenkirche had more to do with Germany's re-unification in 1990 than it did with Dresden's destruction in 1945.

|

Figure 2. The 18th-century Frauenkirche in Dresden, Germany, shown here in ruins in 1991, was destroyed during World War II. (Courtesy of Heinrich Gimmler.) |

|

Figure 3. Reconstructed in 2006, the Frauenkirche closely resembles the original church, shown here in an 1880 photograph. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

As the Frauenkirche example demonstrates, authenticity dialogues surrounding post-conflict reconstructions can shift over time depending on prevailing attitudes and forces at work on a particular site. The three examples detailed below elaborate on the Frauenkirche example, demonstrating how community dialogues around post-conflict reconstructions can result in three broad categories of authenticity. These categories are not normative frames but rather points on a spectrum of responses, all of which are valid if properly understood, documented, and discussed. Community dialogues and reconstruction solutions are rarely egalitarian or democratic but more often propelled by dominant social, political, or economic aims. As such, reconstructions must be construed as authentic expressions of the prevailing discussions of the time, complete with the flaws and disparities that might have accompanied the original monument's creation. Nevertheless, historic preservationists bring to the table valuable perspectives gained by working with buildings that change over time and an acute understanding of how to validate each era of significance as its own authentic expression.

Examples of Post-Conflict Reconstructions

Although many individual examples exist that illustrate the range of responses to conflict-impacted historic buildings, this paper explores three indepth for their clarity in illustrating the primary categories of authenticity in a post-conflict environment. Each site consists of architecturally and culturally significant buildings that were catastrophically destroyed or heavily damaged during conflict, thus permanently changing their material integrity and altering their significance within their constituent communities. As such, discussions involving reconstruction at each site have been steeped in strong opinions from a variety of camps, including professional historic preservationists, the media, community leaders, economic interests, and laypeople. Reconstruction schemes stemmed directly from these discussions, each of which carries far-reaching implications for the authenticity of the buildings as historic artifacts and bearers of cultural significance.

The literal scale of the following examples varies dramatically. Whereas the collapse of the World Trade Center in New York City resulted in nearly 3,000 dead and billions of dollars of damage, the destruction of the Old Bridge of Mostar was relatively inconsequential by comparison. Nevertheless, for the sake of this discussion, the relative scale of cultural loss inflicted upon the people of the United States and the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina, respectively, is assumed to be roughly analogous. Precisely quantifying this metric is obviously quite impossible. As such, rather than focusing on the offenses that lead to the destruction of monuments, the below examples focus on responses chosen by their constituent communities.

Stari Most (Old Bridge), Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Constructed in 1566 by the Ottoman architect Mimar Hayreddin, the 29-meter white limestone, single-spanned Stari Most stood for centuries as a symbol for, and central architectural feature of, Mostar, a thriving, ethnically integrated community in the southwest Balkans.(14) The savage civil wars of the 1990s following the break-up of the former Yugoslavia involved numerous atrocities against cultural heritage, but few were as poignant as the non-strategic destruction of the Stari Most by Croat paramilitary tank fire on November 9, 1993.(15) Due to the nature of the intense, street-to-street fighting in Mostar's Stari Grad (Old Town), many of the city's historically significant buildings in the densely built Ottoman-era quarter were damaged or destroyed, either deliberately or collaterally in months of fierce conflict. In the case of the Stari Most, the message was clear: The bridge had been intentionally targeted, not as a strategic military site, but as the embodiment of a proud Muslim heritage and symbol of a united Mostar. As with the violent obliteration of culturally significant buildings in communities throughout the Balkans during the early 1990s, the removal of the centuries-old Stari Most represented an attempt to erase hundreds of years of ethnic identity and social history.

With the ratification of the Dayton peace accords in Paris on December 14, 1995, the Balkan War came to an end, initiating a massive social, economic, and infrastructure reconstruction project. In a bitter twist of circumstance, Mostar's Stari Grad had won the prestigious Aga Khan Award for architecture in 1986 following a much-admired restoration and revitalization program headed by Bosnian historic preservationist, planner, and architect Amir Pasic. Although the timing of the 1986 restoration seemed particularly cruel—with much of its work reduced to rubble only seven years later—the extensive documentation compiled during the project, along with the city's widely-reported tragic tale, helped spur the following decade's rebuilding effort.

Since the conclusion of the conflict in 1995, internationally aided rebuilding efforts have focused on the Stari Most due to its past significance, along with its newfound symbolism as a "bridge" between rival ethnic groups in the devastated country. A painstaking process of reconstructing the bridge based on the 16th-century plans using stone from the original quarry and employing traditional Ottoman construction techniques formally launched in 1997. In collaboration with UNESCO, as well as a number of other expert organizations, individuals, and donor countries,(16) the World Bank financed the bridge's reconstruction with a $15.8 million, 35-year "Learning and Innovation Loan" as a pilot project aimed at promoting social reconciliation and development through the reconstruction of Mostar's cultural heritage.(17) Acknowledging that reconciliation in a post-conflict environment was a prerequisite for economic regeneration, the pilot project specifically aimed to "improve the climate for reconciliation among the peoples in Bosnia and Herzegovina through recognition and rehabilitation of their common cultural heritage in Mostar."(18) Although the outside investment was largely welcomed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, foreigners' domination of the reconstruction discussions frequently was not. Amir Pasic's role as a Mostarian played a critical role in advancing many of the rebuilding efforts in the Stari Most but many decisions were highly disputed, particularly within the town's Croat community.

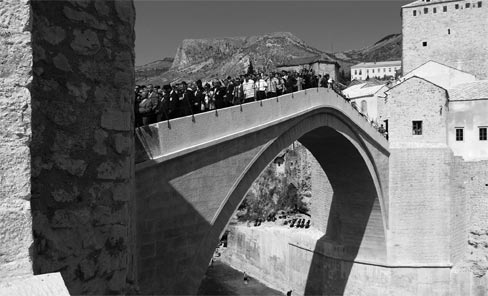

In July 2004, a "new" Old Bridge was rededicated with considerable fanfare, along with weighty expectations of its potential to heal old wounds.(Figure 4) The brand-new glimmering white replica today again graces the banks of the Neretva River, just as its predecessor had for more than 400 years, although with nary a speck of the patina carried by the original building blocks. While few would dispute that the authenticity of the Stari Most was revised by the reconstruction, the span now bears a new kind of historic importance and updated cultural significance to the community to which it has been returned. In July 2005, the "Old Bridge Area of the Old City of Mostar" was inscribed onto UNESCO's World Heritage List as Bosnia and Herzegovina's first World Heritage Site.

Significantly, the site satisfied the World Heritage Committee's "Criterion VI," which requires that a site "be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance" and is used in order to "justify inclusion in the List only in exceptional circumstances and in conjunction with other criteria cultural or natural."(19) This nomination underscores the altered authenticity of the Old Bridge—which might have qualified for the List prior to its destruction under any of the other five criteria—as a result of its role in conflict.

World Trade Center, New York City, USA

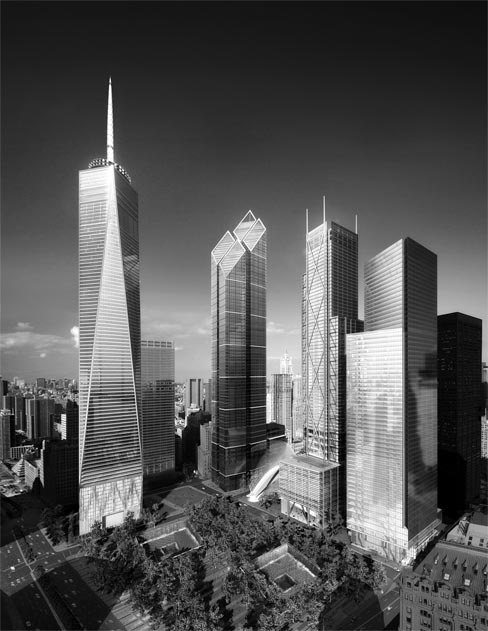

Once the tallest buildings in the world, the World Trade Center towers were constructed between 1966 and 1977 at the southwestern tip of Manhattan based on designs by the Japanese American architect Minoru Yamasaki.(Figure 5) Although initially spurned as intrusive, uninspired eyesores, the Twin Towers ultimately came to define the New York skyline, representing the financial might of New York, and, by extension, the United States. Terrorists destroyed the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, by flying hijacked commercial airliners into the buildings, resulting in an unprecedented level of destruction and loss of life. Within days of the towers' collapse, economic necessity and nationalistic defiance spurred heated debates about rebuilding on the site, a discussion that ultimately escalated to the international level given the nature and scale of the disaster and the prominence of the buildings.

|

Figure 5. Designed and built between 1966 and 1977, the World Trade Center's Twin Towers, appearing in this 1978 photograph with the Brooklyn Bridge, were among the tallest buildings in the world. (Courtesy of the Historic American Engineering Record, Jack E. Boucher, photographer.) |

This discussion probably represented the most widely publicized, highly contentious, and painstakingly scrutinized reconstruction process since the end of World War II. Like the Stari Most, calls for reconstruction sounded hours after the edifices fell. Unlike the Bosnian tragedy, however, the debate around the World Trade Center site involved millions of residents, the highest of financial stakes, and the political will of a military and economic superpower.

Initially, plans to rebuild the towers in-kind were widely considered, enjoying the support of figures such as former New York City Mayor Ed Koch.(20) Other voices came forward, such as Philippe de Montebello, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, calling for the preservation of fragments of the World Trade Center's trademark skin in situ as a memorial.(21) But these proposals soon wilted in the face of the glaring requirements of commercial, economic, and political interests. Members of the architectural community eagerly stepped forward to throw their weight behind a full renewal of the site, minus any significant fragments of the now-ruined buildings.(22) Historic preservationists, for their part, rushed to list the World Trade Center site in the National Register of Historic Places, including in their nomination the original building components left behind by the clean-up effort. The National Register effort, led by New York State Historic Preservation Officer Bernadette Castro, was not the end of the preservation community's engagement at the World Trade Center site. The World Monuments Fund, along with other New York based preservation organizations, led an effort to protect neighboring historic buildings impacted by the towers' collapse from redevelopment projects in Lower Manhattan.(23)

By December 2002, the initial design competition for redevelopment of the World Trade Center site had yielded nine proposals, including several of the world's most recognizable names in architecture. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC), a joint state-city corporation created to oversee the revival of the site and surrounding areas, presided over the competition, ultimately selecting a design known as "Memory Foundations" by American architect Daniel Libeskind in February 2003. Best known for his Jewish Museum in Berlin, Libeskind's selection struck many as a revival solution that combined architectural vanguard with an acute sense of tragedy and commemoration. Observers of the competition and selection results commented on the cathartic undertones of the committee's rejection of several designs that referenced pairs or explicit homage to the Twin Towers. Some critics went so far as to suggest that Libeskind's selection had more to do with the negation of the original World Trade Center's original form and meaning than the particular genius of his design.(24)

Criticism of the World Trade Center site has not been limited to Libeskind's designs. American architect Michael Sorkin has called the design competitions that produced the plans a "waste of energy and imagination."(25) Meanwhile, the LMDC has been subject to persistent accusations of ignoring public and neighborhood input (a climate that recalls the era of omnipotent state agencies that created the original World Trade Center).(26) In a study of Battery Park City residents conducted between 2002 and 2004, the American ethnologist Setha Low found that Libeskind's LMDC-approved plan incorporated none of the design features sought by residents despite the fact that the latter would literally live within the boundaries of the reconstructed site.(27)

The separate but concurrent memorial design competition, launched by the LMDC in early 2003 drew far more submissions, yet no fewer barbs. The LMDC narrowed 5,201 entries from around the globe to eight finalists, among them the eventual winning team of Michael Arad and Peter Walker with their proposal entitled "Reflecting Absence." Memorial competition guidelines included four program elements, the fourth of which encouraged submitters to "convey historic authenticity" by including elements of the old site in the new design.(28) Arad and Walker (among others) addressed this directive by using the Twin Towers' footprints to frame reflecting pools, ramps and cascades designed to function as "large voids, open and visible reminders of [the World Trade Center's] absence."(29)

The use of "absence" to satisfy a historic authenticity requirement—even in a newly constructed memorial—underscores the variability in authenticity determinations at post-conflict reconstruction sites. While the Libeskind tower proposal as imagined by the LMDC clearly conveys renewal, the comprehensive site design that includes Arad and Walker's memorial sends the more complex message of renewal mixed with an authentic representation of loss. As cultural critic Marita Sturken puts it, "one could argue that the desire to rebuild the towers and the designation of voids where the towers once stood are essentially the same."(30)

By 2004, reconstruction officially commenced with the cornerstone setting for the new, so-called "Freedom Tower," a single edifice sharing nothing with its predecessors other than its aspiration to claim the world's tallest building title.(Figure 6) Although many questions remain regarding the success of the memorial and new building project, the tabula rasa decision carries significant implications as to the authenticity conveyed by the new structures, not to mention that maintained by the site itself. Concurrently, the few original materials or site features (including the memorial-tower footprints) that do remain will possess a profoundly altered level of authenticity, both in their new interpretive context and relationship to the new structures. The ongoing conflict between populism and elitism in the design process, and democracy and big-money real estate interests in the decision-making process, muddies the waters of clear, constituent oriented dialogue that can produce an authentic reconstruction. Use of the term "Ground Zero" seems to have preordained the tabula rasa approach to the site, and the remarkably aggressive reconstruction time frame speaks to the economic and political forces driving the process. Nevertheless, the result will represent an authentic response to the lost buildings themselves, as seen through the lens of the process that drove the site's revival.

|

Figure 6. Once complete, the Freedom Tower will be the tallest building constructed around the memorial park on the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan. (Courtesy of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP/dbox Studio, reproduced with permission.) |

Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche (Memorial Church), Berlin, Germany

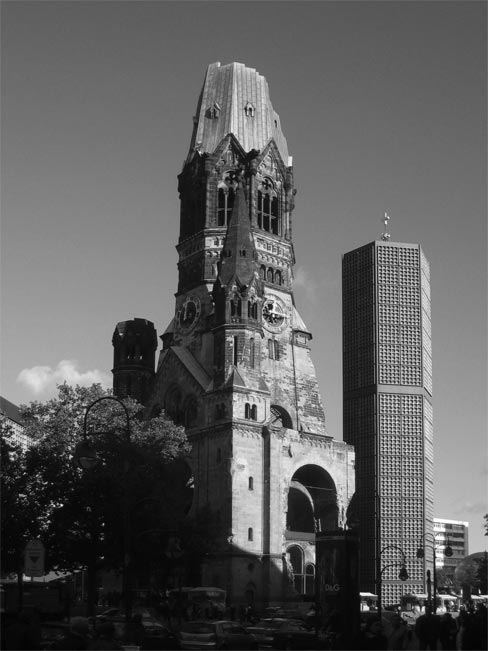

Franz Schwechten designed this monumental neo-Romanesque church, completed in 1895, as a memorial to the glory of the short-lived German Empire and its leader, Kaiser Wilhelm I.(Figure 7) Ultimately viewed as a symbol of a united, greater Germany following the Kaiser's defeat in World War I, the Church also served as an important landmark and community resource in Berlin's surrounding Kurfürstendamm neighborhood. British air raids destroyed most of the building on November 22, 1943, leaving only its central tower and a portion of the nave as a graphic, war-scarred reminder of the widespread destruction of Berlin during World War II.

|

Figure 7. This circa 1900 print shows the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church (Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche) in Berlin, Germany. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

After the war, debate swirled for a decade over how to deal with the church's congregation, and ultimately the ruins themselves. From the beginning, nearly all proposals called for demolition of the 19th-century remains and construction of a completely new structure. In 1955, the church was denied protection as a designated monument, thus underscoring the official historic preservation community's lack of enthusiasm for reconstructing it in its original form (or, for that matter, preserving the ruin).(31) Subsequent design competitions yielded several solutions that incorporated rubble from the site as a cladding for new buildings, but none seriously considered weaving the existing fragments into a new plan.

After several false starts, a design by the Egon Eiermann surfaced in March 1957 as the preferred approach. A devoted modernist, Eiermann's initial solution—like its predecessors—called for the removal of all fragments of the ruined building except for rubble that the architect intended to use as paving. Within five days of the release of Eiermann's design, local residents of (then West) Berlin vociferously protested, spurring officials to request that the architect revisit his approach so that the old tower could be retained. Although Eiermann begrudgingly accepted his new instructions, he acknowledged the new composition's ability to act as a vehicle for carrying the original building's authentic experience well into the future. "My wish is for [future generations] to have an understanding for those who experienced the terror, and for whom the ruin symbolizes their own sufferings," he remarked at the time.(32)

Eiermann's response to the public's and competition organizers' demands is an octagonal concrete and blue glass church, bell tower, and associated buildings, which were completed in 1963 (a small museum memorializing the war damage and the building's former 19th-century splendor was later installed in the old tower).(33) Today, the striking composition stands as a reminder of the bombed out wasteland that was old Berlin following World War II.(Figure 8) Central to this presentation are the original church components, structurally stabilized, but still pocked and blackened as they were in 1943. Although Eiermann's new church, along with the surrounding area, effectively conveys the economic and cultural recovery of post-War Germany, the original Kaiser Wilhelm Gedächtniskirche explicitly reminds present-day viewers of the city's traumatic experiences more than 60 years ago.

|

Figure 8. This 2006 view of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin shows the preserved tower ruin and architect Egon Eiermann's bell tower. (Courtesy of Manfred Brueckels.) |

New Categories of Authenticity for Post-Conflict Sites

Each of the above examples reflects a post-conflict reconstruction process that involved considerable debate and discussion among community members, leaders, and historic preservationists, but it remains unclear whether the participants fully understood the authenticity implications of each decision. Recalling Brandi's emphasis on a building's history in addition to its creation, how can people define these reconstructed "artworks"—each of which possesses considerable cultural and historical significance, in some cases validated by leading cultural institutions such as UNESCO—to current and future stakeholders? Similarly, how can historic preservationists effectively convey these different shades of authenticity to community stakeholders as future discussions regarding damaged sites emerge? In order to address these challenges facing professionals and the public alike, this paper proposes the following three categories of authenticity that specifically apply to post-conflict reconstructions.

Authenticity of Connection

A building or site may possess authenticity of connection when it is faithfully and precisely recreated as an expression of continuity with its pre-conflict social, environmental, and cultural conditions. In cases such as the Stari Most, this approach can restore traditional use and perpetuate (or even enhance) the significance of the lost artifact, but it may imply a diminishment of the relationship to the historic period that resulted in its destruction.

Authenticity of Renewal

Authenticity of renewal may exist when a conflict-damaged site is wiped clean of its original buildings and an entirely new structure (or structures) is installed in its place. The "Freedom Tower" design, "Reflecting Absence" memorial, and limited preservation efforts around the World Trade Center's original building components likely will convey a powerful, somber, and complex message about the traumatic events that took place on the site. But, as with the authenticity of connection, the near-total absence of material authenticity combined with a singular emphasis on revival risks conveying a mixed message about the artifact's authentic historical experience. At the same time, the explicit void that is central to the planned memorial suggests its own kind of "reconstruction" of the lost structures.

Authenticity of Experience

This third category represents those buildings or architectural assemblages that explicitly reflect damage incurred through conflict as a graphic reminder of the traumatic episode. Eiermann's design for the new Kaiser Wilhelm church deliberately and evocatively leverages the original monument's materials, along with its painful past, to create a composition reflecting the authentic experience of Berlin's past 60 years. Although the burnt out 19th-century tower remains agonizing to view, it hides little from present and future viewers regarding the site's creation, history, and new role within the community.

When accompanied by a sufficient level of historic documentation and discussion at the local level, each of the above approaches can result in a completely valid, "authentic" historic artifact. Furthermore, as discussed in the Nara Document (among other treatises), material authenticity must not hold a monopoly on authenticity designations from the perspective of the historic preservation discipline or the community at large. Indeed, the field should recognize community action in response to historic events as a product of its time that carries its own hue of authenticity.

The above categories place a high level of responsibility on cultural resource professionals in helping manage authenticity requirements for the communities in which they work. In order to do so, these professionals must apply their collective expertise in the fields of history, interpretation, and materials conservation as they pertain to historic buildings in order to help communities decide upon an acceptable level of authenticity in post-conflict buildings. Having aided in this decision making process, historic preservationists will be better equipped to interpret the sites for future generations. Communities, for their part, can better integrate the revised authenticity carried by the reconstructed artifact into post-conflict recovery processes.

About the Author

An archeologist and historic preservationist by training, Robert Garland Thomson works for the Presidio Trust in San Francisco, California.

Notes

1. This essay is based on a paper, "From Mostar to Manhattan: Authenticity in the Context of Post-Conflict Reconstruction," presented at the Fifth National Forum on Historic Preservation Practice ("A Critical Look at Authenticity and Historic Preservation") held March 23-25, 2006, at Goucher College, Baltimore, Maryland.

2. Jukka Jokilehto and Joseph King, "Authenticity & Integrity: Summary of ICCROM Position Paper," UNESCO (February 2, 2000), http://whc.unesco.org/events/gt-zimbabwe/jukka-a.html, accessed on April 20, 2005.

3. Geoffrey M. White, "National Subjects: September 11 and Pearl Harbor," American Ethnologist 31 no. 3 (August 2004): 298.

4. John Stubbs, "Nomenclature in Architectural Conservation," unpublished course material for International Historic Preservation Practice course (Columbia University, spring 2005).

5. Knut Einar Larsen and Jukka Jokilehto, eds., Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to the World Heritage Convention, 1994: Nara, Japan (Paris, France: UNESCO, 1995), 4.

6. Jukka Jokilehto, "Viewpoints: The Debate on Authenticity," ICCROM Newsletter 21 (1995): 6-8.

7. Vasiliki Kynourgiopoulou, "Authenticity: Reality versus Imaginative Reconstruction—Self Promotion as a Criterion for Identity and Place," EAR 27 (2000): 101-26.

8. Eman Assi, "Searching for the Concept of Authenticity: Implementation Guidelines," Journal of Architectural Conservation 6 no. 3 (2000): 60-9.

9. Paolo Marconi, "Restoration and Reconstruction: As it Was, Where it Was?" Zodiac 19 (1998): 40-55.

10. Setha Low, "Social Sustainability: People, History and Values," in Managing Change: Sustainable Approaches to the Conservation of the Built Environment, proceedings from the 4th Annual US/ICOMOS International Symposium, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 2001, eds. Frank Matero and Jeanne Marie Teutonico (Los Angeles, California: Getty Conservation Institute, 2003), 62.

11. Karrie Jacobs, "The Power of Inadvertent Design," Metropolis 23 no. 6 (February 2004): 54.

12. Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties (36 CFR 68.3).

13. Reconstruction of the Great Buddha in the City of Nara in the Edo Period (Nara, Japan: Nara Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan, 2005), 57.

14. Amir Pasic, The Old Bridge (Stari Most) in Mostar (Istanbul, Turkey: Research Centre for Islamic History, Art, and Culture [IRCICA], 1995.

15. The bridge had already been damaged by mortar assault in 1992 by Serb dominated federal Yugoslav army forces. Although they failed to destroy the span completely, the erstwhile Croat allies of the Bosnian population finished the job 19 months later.

16. Donor countries included Italy, the Netherlands, France, Turkey, and (notably) Croatia. Donor and partner organizations included the Council of Europe Development Bank, UNESCO, AKTC, WMF, and the local municipality of Mostar.

17. The World Bank, World Bank Investment in Cultural Heritage and Development: Bosnia and Herzegovina Pilot Cultural Heritage Project (Washington, DC: The World Bank Group, 2002), 23.

18. The World Bank, Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Credit in the Amount of SDR 3.0 million (US $4.0 Million Equivalent) to Bosnia and Herzegovina for a Pilot Cultural Heritage Project (Washington, DC: The World Bank Group, 1999), 2.

19. UNESCO World Heritage Centre, "The Criteria for Selection," http://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/, accessed on February 13, 2007.

20. Real estate developer and celebrity Donald Trump also advocated precise reconstruction, albeit one-story higher than the originals.

21. Setha M. Low, "The Memorialization of September 11: Dominant and Local Discourses on the Rebuilding of the World Trade Center Site," American Ethnologist 31 no. 3 (August 2004).

22. Philip Nobel, "On Not Falling for Ruins: Memorializing the Wreckage of the World Trade Center Would Mourn Only the Architecture," Metropolis 21 no. 4 (2001): 68.

23. Sara Kugler, "Preservationists Urge Saving Historic Structures During WTC Redevelopment," http://nycpreservation911.org/html/ap.html, accessed on April 20, 2005.

24. Marita Sturken, "The Aesthetics of Absence: Rebuilding Ground Zero," American Ethnologist 31 no. 3 (August 2004): 319.

25. Sturken, "The Aesthetics of Absence," 321.

26. Peter Marcuse, "What Kind of Planning After September 11?" in After the World Trade Center, ed. Michael Sorkin (New York, New York: Routledge, 2002), 154.

27. Low, "The Memorialization of September 11," 337.

28. Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition, "Competition Guidelines," April 28, 2003, http://www.wtcsitememorial.org/pdf/LMDC_Guidelines_english.pdf, accessed on February 12, 2007.

29. Michael Arad and Peter Walker, "Reflecting Absence: Statement," January 14, 2004, http://www.wtcsitememorial.org/fin7.html, accessed on February 13, 2007.

30. Sturken, "The Aesthetics of Absence," 322.

31. Kai Kappel, "Raster vs. Ruin: The Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedachtniskirche in Berlin," in Egon Eiermann: Architect and Designer, the Continuity of Modernism, ed. Annemarie Jaeggi (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004).

32. Wolfgang Pehnt, "Six Reasons to Love Eiermann's Work, and One Reason Not to Love It," in Egon Eiermann: Architect and Designer, the Continuity of Monderism, ed. Annemarie Jaeggi (Ostfildern-Ruit, Germany: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004).

33. "One, Two, Three," Architectural Forum 124 no. 2 (1966): 76.