Article

The Accokeek Foundation and Piscataway Park

by Denise D. Meringolo

Introduction(1)

In the spring of 2005, on the eve of its 50th anniversary, the Accokeek Foundation—one of the nation's oldest land trusts—was working to articulate its specific role as steward, with other stakeholders, of a complex cultural landscape along six miles of riverfront in Prince George's County, Maryland.(2) The property, approximately 11 miles from the District of Columbia line and directly across the Potomac River from George Washington's historic home, Mount Vernon, is jointly managed by the Moyaone Reserve (an environmentally conscious planned community), Piscataway Park (a unit of the National Park Service), and the foundation. The fields, trails, shoreline, and interpretive areas of Piscataway Park were shaped, not only by historical and environmental forces, but also by evolving relationships among the National Park Service, the Moyaone Reserve, environmental advocacy groups, historic site managers, farmland preservation groups, and others. The Accokeek Foundation was looking for ways to integrate multiple views and valuations of the landscape into a new vision to guide its mission.

The foundation's complex purpose was rendered somewhat invisible to most casual visitors, because the effort leading up to the founding of Piscataway Park magnified the importance of one very powerful view. By protecting the woods, fields, and watershed on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, Piscataway Park preserves the historic view from former President George Washington's Mount Vernon. National Park Service evaluations of the site tended to note its historical, architectural, natural, and archeological features, while at the same time downplaying the importance of those features to emphasize the park's role in preserving historically significant scenery. The National Register of Historic Places nomination form, for example, completed in 1979, noted that—

Piscataway Park is principally significant for its role in maintaining the vista across the Potomac River from Mount Vernon. As the only unit of the National Park System established specifically to protect the environment of a privately owned historic property, it is secondarily important as a new departure in the recent history of Federal conservation activity. The park itself is not significant for particular on-site landmarks or features excepting the separately nominated features referenced in section 7 [the Accokeek Creek site and Marshall Hall]; its value derives from its general scenic character as viewed from across the Potomac.(3) |

The significance of the view across the river is not contrived: It is thoroughly documented that Washington loved his view of the Maryland shore. During a major renovation of the main house in 1774, he built a two-story piazza overlooking the river. Numerous guests to the mansion recorded their appreciation of the view. The American architect Benjamin Latrobe sketched the scene. The topographical writer Isaac Weld wrote of his visit in the mid-1790s, "The Maryland shore, on the opposite side, is beautifully diversified with hills, which are mostly covered with woods; in many places, however, little patches of cultivated ground appear, ornamented with houses. The scenery altogether is most delightful."(4) Significantly, Latrobe and Weld captured the scenic and aesthetic aspects of the view, including the houses and fields visible from Mount Vernon. The undeniable attractiveness of the landscape proved a valuable rallying point for galvanizing diverse groups and individuals around the common purpose of protecting the area from potentially unsightly development.

Most successful national parks and historic sites balance the interests of multiple stakeholders on constantly shifting ground. While it is often necessary to create strategic alliances to achieve some political purpose, the creation of common ground—whether intellectual or physical—carries a profound sense of authority that can unintentionally obscure the complexity of the past, limiting both the educational potential and social value of public space. This essay seeks to broaden perspectives about the meaning of nature, agriculture, and community in and around Piscataway Park by focusing on the Maryland shore itself. It examines the ways different communities valued the landscape—ways that George Washington and his peers could not have seen.

Agricultural Value

The agricultural heritage of Prince George's County, Maryland, dates back more than 1,000 years. When Captain John Smith explored the Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac in 1608, he visited the area near Piscataway Creek and recorded the name of a Native American settlement: Moyaone. Nomadic people had lived in the area and returned repeatedly to the Potomac shoreline for some 4,000 years before the arrival of European explorers and colonists. But the Moyaone village was home to a specific group—the Piscataway people—who built a permanent enclosed village and developed an agricultural economy around the year 1200.(5)

English colonists and enslaved Africans began settling in the region shortly after Smith's voyage, and Maryland quickly became one of Great Britain's most successful colonies. The Maryland colonists produced agricultural goods and raw materials that provided a benefit to the royal economy and created little competition for British manufactured goods.(6) Corn and wheat grew well and were stable sources of income for most planters, but the colony's main cash crop was tobacco. The poor planters and tenant farmers—indeed, the entire region—depended on tobacco for their livelihood. When tobacco was in high demand in Europe, Prince George's County prospered. When the tobacco crop failed or demand shrank, so did the fortunes of Prince George's County families.(7)

At first, the Piscataway people and other Native Americans co-existed with European colonists, but the two peoples viewed property differently, and cooperation quickly gave way to competition. Native American leaders made an effort to accommodate the colonial government, petitioning for formal recognition of their land rights and signing a number of treaty agreements. By the middle of the 17th century, European colonists in Prince George's County had acquired large tracts of land and established farms and tobacco plantations. The competition for fertile land eroded relationships among Native Americans and Europeans. It resulted in bloodshed on a number of occasions.(8) William Calvert patented property on the south shore of Piscataway Creek, hoping that setting aside the land for native people might ease tensions. Unfortunately, hostilities continued to escalate, and the Piscataway people formally abandoned Moyaone between 1675 and 1682, though some of them remained in the region.

Tobacco cultivation shaped the culture and landscape of Southern Maryland throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. It required attention year-round from all capable members of the plantation household and increased planters' dependence on slavery. By 1750, half of the households in Prince George's County included slaves. Wealthy planters owned between dozens and hundreds of enslaved Africans and African Americans, but most others operated on a smaller scale. Middling planters who owned property (and even some tenant farmers who did not) relied on the labor of at least one or two enslaved people. The wealthiest plantation owners in the county tended to build their family homes on crests overlooking the agricultural fields; slaves and overseers lived in cabins near the fields.(9)

By the 1770s, growth in Prince George's County had come to a halt. Up to that time, each generation of planters had subdivided their property to create farms for their sons, calculating 50 acres as the minimum size from which a tobacco planter could enjoy a measure of financial success. Endless subdivision was simply not sustainable, and by the late 18th century, it was difficult, if not impossible, for planters to pass land down to their sons. Furthermore, the demand (and price) for land in Prince George's County had increased by this time, making less land available for lease or purchase. Unable to establish new farms, many young men left the county.(10)

Rural Ideal

Beginning in the 1920s, a new group of people discovered the Accokeek shoreline. At first, they arrived as weekend guests, and a few stayed as boarders during the New Deal Era. By the mid-20th century, they had created a permanent community in Accokeek. This self-selected group of government scientists and middle managers shared a common interest in conservation and a similar view of the shape and meaning of the landscape. Bernie Wareham, one of the new residents, seemed to echo the sentiments of Weld when he described the moment he decided to build a house in Accokeek—

We…found our way through the valley, over to the old tobacco barn, a little further, a beautiful sight, beautiful place for a house, flat lands…. We came back to the road to this little hilltop. And that's where we found a little tree out there, a little tree I climbed up. Then I had a beautiful view of Mount Vernon over there.(11) |

As Wareham's description suggests, this wave of newcomers experienced the landscape as passive rural space, a relaxing retreat from urban pressures. Within 40 years, they transformed their personal appreciation for the scenery into political action, spearheading a public campaign that redefined the value of the landscape and fostered the creation of Piscataway Park.

Although many of the men and women who moved to the area had experienced farm life as children, they mostly approached agriculture as a hobby, a personal venture that protected them from dependence on outside aid in an emergency but integral to attaining a rural ideal. They were not alone in harboring such ideas. Many people believed (and still do) that rural working landscapes had a rejuvenating power, that agricultural life signified independence, and that access to nature was a cure for fatigue, ill health, and other debilitating symptoms of a cosmopolitan lifestyle and urban existence.(12)

Henry Ferguson, one of the earliest to arrive, was a scientist employed by the U.S. Geological Survey. His wife, Alice, was a well-educated artist and entrepreneur. Longtime residents of Georgetown in Washington, DC, they counted scientists, ministers, and the politically well connected among their friends and colleagues. Seeking a quiet weekend refuge, they bought a 130-acre farm on the eastern bank of the Potomac River in 1922.

According to Alice's memoir, the lack of amenities was part of the farm's charm. They dubbed the place Hard Bargain, and spent many weekends there, enjoying the woods and fields and playing at rural living. Alice and Henry were hardly agricultural experts, but they held to romantic ideas about the purity and healthfulness of farming. They practiced farming during their stays at Hard Bargain but employed a resident farmer to do most of the work.(13) Their appreciation for the aesthetic and playful pleasures of rural life helped fuel a small but significant interest in the Accokeek shoreline.

Suburban development pressures also played a role in fueling interest in the shoreline. Whereas urban sophistication and rural beauty were complimentary opposites, suburbanization magnified and focused the fears of both city dwellers and nature lovers.(14) During the early decades of the 20th century, most people thought of urban centers as cosmopolitan, intellectual, and exciting, and the rural countryside as an authentic representation of American values. Suburban areas occupied the zone between country and city and almost immediately came to symbolize a kind of cultural limbo. Social commentator Lewis Mumford described the suburbs in 1921 as a wasteland, and his contemporary, the writer and historian Frederick Lewis Allen, criticized the suburbs as hotbeds of conformity, a "socially and aesthetically empty" world.(15)

Suburban development brought significant changes to the social organization and appearance of the national capital region during the 1930s and 1940s. Increasing numbers of federal workers flooded Washington, DC, first to work in New Deal agencies and then to support the war effort. These transplants required housing and services. At first, temporary boarding houses seemed sufficient, but as more people established roots in the region, suburban development soared. Planned suburbs, including Greenbelt, Maryland, touted the benefits of a lifestyle in which transportation, services, and homes were functionally integrated and pleasantly landscaped.(16) Federal initiatives, furthermore, broadened opportunities for home ownership, which many middle class Americans embraced.(17) This suburban development had a profound environmental impact, replacing woods with pavement and reshaping natural landscape contours into a more artificially orderly environment. Some Americans found these trends disturbing.(18)

The Fergusons' most frequent visitors were predisposed to distrust suburban development. Throughout the 1930s, Hard Bargain attracted an eclectic group seeking escape from the increasing clamor of life in Washington. The Fergusons housed many visitors and a few boarders in Longview, a small farm building turned guesthouse. Prior to World War II, the Longview group included a particularly close-knit set of regulars, including Robert Ware Straus, then one of former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes's staffers, an artist named Lenore Thomas who later married Straus, and an architect named Charles Wagner.

As suburban development spread closer to the Accokeek shoreline, the Fergusons and the Longview group hatched a plan to avoid the throngs.(19) Unwilling to see the woods around Hard Bargain cleared and the fields subdivided for apartment buildings and businesses, Alice Ferguson began purchasing hundreds of acres of land around her property. Her real estate venture, the Moyaone Company, was a nod to the first settlement on the Accokeek shore. Straus and Wagner were among the first to buy property.(20) Throughout the 1940s, the Fergusons, Straus, and Wagner continued to market and sell tracts of Moyaone property to carefully screened friends and colleagues. Wagner designed a number of houses in the area, modeling them on the open plan and site sensitive designs of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

Information about the community spread by word of mouth through government offices, from secretary to manager and back again. Alice Ferguson, interested in surrounding herself with like-minded conservationists and conversationalists, interviewed potential buyers. William Harris recalled his own meeting with her: "Alice said, 'What do you do?' And I said, 'I'm a metallurgist.' And she said, 'Oh, too bad. We wanted a botanist this time.'"(21)

When Alice Ferguson died in 1952, she bequeathed land and mortgage notes to Straus, Wagner, and the other Moyaone residents. At first uncertain about how to proceed, the group used the money (about $40,000) to establish more formal channels for developing the rural reserve. They established three interrelated associations to administer the gift. The Piscataway Real Estate Company took over the business of real estate, advertising available lots, interviewing potential buyers, and helping to finance those who seemed most in tune with the community's conservation goals. The Moyaone Company became the Moyaone Association, a nonprofit group that took on the role of establishing common areas, issuing a community newsletter, and policing community standards. The Moyaone Association members also established committees—including a public affairs committee—that explored more serious conservation measures and other programs. Finally, the Alice Ferguson Foundation emerged as a nonprofit association dedicated to conservation and nature education.(22)

Significantly, all the Moyaone residents actively participated in defining and gradually formalizing the role of these organizations as conservation entities. What began as personal preference evolved into a private arrangement among the members of a planned community. Those who bought property agreed to abide by strict residential covenants that prevented unnecessary clearing of the woods and prohibited apartment buildings, billboards, and storefronts.

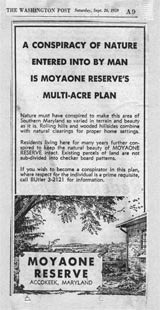

Their willingness to agree to these conditions grew out of a common set of formative experiences. Many had grown up on farms but had left behind a rural childhood for urban job opportunities. They had lived through the Great Depression as children and had survived as young adults through World War II. Taken as a whole, these experiences left them with a certain amount of nostalgia for an agricultural past and a measure of distrust in the ability of any government to ensure their security.(Figure 1) E. Lee Fairley summarized their common sensibility this way: "We were all city folk. The motivation essentially for coming out here was to get away from the city. And it was also recently enough after the end of the war that there was concern about living in an urban area."(23) William Harris, another early resident of the Moyaone, recalled, "It was no utopian philosophy that brought us here. It was very practical Depression and World War II experience that said we wanted to be in a place that if worse came to worse we could just pull the land around us and survive."(24)

|

Figure 1. This advertisement for the Moyaone Reserve, appearing in the September 26, 1959, edition of the Washington Post, aptly summarizes the residents' concern for preserving the area’s natural beauty. (Courtesy of the Accokeek Foundation, Moyaone Collection.) |

Not everyone living on the Accokeek shoreline between Marshall Hall and Piscataway Creek was a resident of the Moyaone. A number of farming families owned large parcels nestled alongside the new reserve, and the Depression and World War II affected them differently. As the population of the Moyaone increased, a rather subdued sense of uneasiness began to ripple through the farms. While Moyaone attracted people who appreciated the character of the landscape, their calculation of its value differed in significant ways from that of families who had operated farms in the area for decades. Unlike their new neighbors, the farmers viewed the land as an evolving resource. If the Depression had hurt their investment, then the boom in postwar suburban development could help recover the loss. Manning Clagett, whose family owned particularly valuable tracts of land on the river, including an area called Mockley Point,(25) recalled somewhat wistfully, "We had the best… waterfront area… and it could have been developed real nice… all the waterfront could have been developed into, well, a lot of things that are open to the public. You could have had golf courses, marinas and the whole works."(26)

Although farming families like the Clagetts were less likely than Moyaone residents to oppose recreational and suburban development on the Accokeek shoreline, they agreed that some forms of development were unacceptable. Rumors of industrial development at Mockley Point and elsewhere on the Potomac River shoreline made both groups uneasy because of its negative impact on the scenic and financial value of the land. When such change seemed inevitable in the 1950s and 1960s, farming families formed temporary, strategic alliances with the Moyaone residents. Their willingness to support some conservation efforts affected their ability to prevent other forms of conservation about which they were less enthusiastic. During the final decade leading up to the creation of Piscataway Park, farmers and Moyaone residents often found themselves at odds over the precise meaning and value of the Accokeek landscape.

Creating Piscataway Park

During the 1950s, it became increasingly clear that the restrictive covenants, screening of prospective buyers, and other private means of conservation adopted by the Moyaone Association were insufficient to stop suburban encroachment. As development pressures mounted, a third group became actively involved in efforts to extend permanent protection to the Accokeek shoreline. Cecil Wall, resident director of Mount Vernon in Virginia, kept a watchful eye on the quality of the vista from across the Potomac River. Concerned that the demand for housing and services would place unsightly developments in the background of every tour of George Washington's historic home, Wall began actively promoting the value of the view from Mount Vernon. He told a reporter in 1956—

This is what seems to impress our distinguished visitors most. You know the routine. The State Department brings them out, crowned heads, prime ministers, presidents of republics and foreign ministers. After their tour of Mount Vernon they stop here to be photographed. They all express amazement that the view is so unspoiled.(27) |

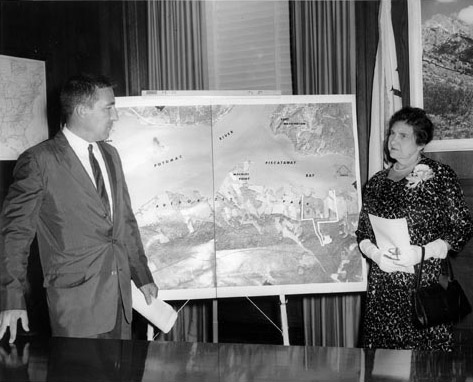

Wall and the members of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association (MVLA) became the Moyaone Association's most visible champions in the effort to protect the landscape. Over the next decade, the MVLA undertook a massive campaign to promote the value of the view from Mount Vernon as a scenic and historic backdrop intimately associated with the nation's first president.(Figure 2)

The campaign began in earnest in 1954. That year, a tract of 483 acres of waterfront property and farmland bordering the Moyaone and within clear sight of Mount Vernon went up for sale. Rumors that a Texas oil company wanted to build storage tanks on or near the property caused a stir among conservation-minded residents on both sides of the Potomac. Many people worried that, without intervention from a conservation-minded buyer, the pristine shoreline would give way to unsightly industrial development.

Aware of the National Park Service's efforts to preserve the view along the George Washington Memorial Parkway and its interest in Mount Vernon as part of the cultural landscape, Wall contacted the Department of the Interior about the sale.(28) Meanwhile, Wagner independently searched for a private buyer willing to adhere to the Moyaone Reserve's land covenants. Neither man succeeded in solving the problem on his own; when they combined resources, however, they set in motion the events that led to the creation of Piscataway Park.

Although it is difficult to determine who made the first move, Wall's notes indicate that he began communicating with Wagner during the spring of 1955.(29) The two men discussed their mutual interest in protecting the character of the Accokeek shoreline and considered all options, from private purchase to federal intervention. Wall found a key ally in Frances Payne Bolton, a Congresswoman from Ohio and a regent of the MVLA. In a letter to Bolton he wrote—

I have been intending for some time to call you and urge some further action toward stabilizing the view across the river, but occasional conversations with [your assistant] have made me realize how many and pressing your other engagements have been and I have deferred from week to week. However, I have just had an informative telephone call from a neighbor, Mr. Charles Wagner, who lives across the river. This call, together with our failure to get the President out here and interest him, makes me feel that fresh approaches should be considered.(30) |

Bolton appreciated the historical significance of the view from Mount Vernon and had already expressed support for Wall's efforts to involve the Federal Government in protecting it. Wall persuaded her to take a more active role. When her own effort to find another buyer failed, Bolton agreed to buy the property herself.(Figure 3) Once she owned the property, she, Wagner, Straus, Wall, and a handful of other advisors and Moyaone residents began to develop a plan to ensure the permanent protection of the Accokeek landscape and the view from Mount Vernon.

According to his memoir, Straus met with Bolton privately in Ohio in the summer of 1955. They agreed that private purchase alone would not protect the Accokeek landscape and discussed the need for a more comprehensive approach. Bolton gave the Moyaone Association a $5,000 grant to develop a strategic plan, and Straus hired historian Frederick Gutheim as a consultant. Gutheim recognized the importance of a unified front, and he recommended the creation of a single nonprofit entity to represent the different parties interested in saving the property from development.(31)

Acting on Gutheim's recommendation, Straus pushed the Moyaone Association to create yet another nonprofit entity that would hold private lands in trust and educate the public about the value of conservation. Chartered in 1957, the Accokeek Foundation became one of the nation's earliest land trusts. Bolton agreed to serve as the foundation's first president, effectively cementing the partnership between the MVLA and the Moyaone Association.(32)

Meanwhile, the Moyaone Association pursued other avenues for protecting the land in the reserve in perpetuity. Hopeful that zoning measures might protect open space and forest, Straus and others approached the Prince George's County government about including their community under the planning authority of the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission.(33) Both the Moyaone and the Accokeek Foundation also explored how they might formalize the terms of the reserve's land covenants. In 1956, they began to study the potential effectiveness of scenic easements, examining proposals made for the use of easements in protecting other scenic views.

At Accokeek, planners concluded that both the public view from Mount Vernon and the private property rights of Moyaone residents would be adequately protected if residents agreed to donate scenic easements to the Department of the Interior. At the time, easements were largely unknown or untested in private historic preservation situations.(34) No legislation existed in Maryland to compensate landowners who gave up specific rights to their property. Some of the Moyaone residents thought the easements were redundant, since covenant agreements had already limited their ability to alter the landscape. The lack of an obvious economic benefit for preserving open space and scenic vistas made easements a tough idea to sell.

In 1960, new threats to private property on the Maryland shore made it necessary to come to agreement on the value of the landscape. The Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) announced plans to locate a sewage treatment plant on Piscataway Bay in clear view of Mount Vernon. The WSSC identified Mockley Point, a waterfront property owned by farmer Henry Clagett, as the likely location for the plant. To make matters worse, the WSSC, though it was not a government entity, had the power of eminent domain.

Very quickly, the Accokeek Foundation, the MVLA, and the Moyaone Association focused their energies on preventing the WSSC from taking Mockley Point. They assembled a coalition of nature conservancies, historic preservationists, community associations, farmers, politicians, and others to lobby the Prince George's County Commissioners for official intervention. In January 1961, representatives from dozens of groups crowded into a Commissioners' meeting to register their opposition to the plant. Although each group presented its own reason for opposing the plant, the argument that carried the most weight came from Mount Vernon. A reporter for The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin described the meeting in the following manner—

Most of the 300 or more people jammed into the Upper Marlboro courtroom had quite a lot to say against the location of a sewage treatment plant at Mockley Point, but it wasn't their testimony that was deciding the issue. Nor was it the testimony of the WSSC, which presented engineering studies favoring a plant at or near the mouth of Piscataway Bay, just across the River from MV. The Big Man who dominated the entire evening settled the argument in his favor without saying a word, without even being present. No one could doubt that GW did not want a treatment plant obstructing the view from MV. And that was that.(35) |

In the meantime, Bolton had won strong allies in Congress, including U.S. Representative John Saylor of Pennsylvania and Senators Clinton Anderson of New Mexico and Wayne Aspinall of Colorado. On October 4, 1961, President John F. Kennedy signed Public Law 87-362, the first of several to authorize the creation of a federal park on the Accokeek shoreline to protect the view from Mount Vernon.(36)

The residents of the Moyaone were committed to preserving the rural character of their community, but they shared with local farmers a hesitation about inviting the Federal Government to assert any control over their use and enjoyment of the landscape.(37) Both groups agreed only reluctantly that government intervention was necessary to prevent the WSSC from condemning and seizing Mockley Point. Dixie Otis, a member of the Moyaone Public Affairs committee recalled, "I think, everybody would have preferred to be able to preserve the land without having to get the Federal Government involved, but there was just no other way."(38) Similarly, according to an editorial in the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, Henry Clagett had told the WSSC that he would never sell Mockley Point to them, and once the threat of losing his land to condemnation became more viable, he signed on to the conservation effort, joining in the appeal to Congress to acquire the land.(39)

As it turned out, cooperation between local farmers and the residents of the Moyaone Reserve was strategic but fragile. As plans for the park moved forward, conservationists began to define and popularize particular beliefs about the value of the Accokeek landscape. The view that seemed to best suit the framework of a National Park Service property differed considerably from the views held by most farmers. Further, the close alliance of the Moyaone residents with the Accokeek Foundation and the MVLA tended to amplify farmers' concerns that their land values were being threatened by outsiders who stood to benefit personally from the creation of the park.

Shortly after President Kennedy authorized the creation of a national park on the Accokeek shoreline, the Accokeek Foundation, the Moyaone Association, and the Alice Ferguson Foundation began to develop a plan under which private residents could remain on their property and participate in the preservation of the landscape. On New Year's Eve, 1961, members of the Moyaone's public affairs committee met with three representatives from the local farming families. The farmers felt that the proposed park was a project of the Moyaone, and that federal interest had only replaced the threat posed by the WSSC with a new threat. In either case, farm families faced the danger of losing rights to use and dispose of their own property and wanted to be able to develop their property without interference from either the Moyaone or the Federal Government.

The Moyaone Association continued to explore the possible effectiveness of scenic easements as a tool for protecting private property and the view from Mount Vernon. In January 1962, the association established a special committee on easements. A quick survey of Moyaone landowners indicated that 10 supported scenic easements, 10 opposed them, and 5 were undecided. As word about the Moyaone easement plan spread, opposition increased, and the relationship between the farm families and Moyaone residents deteriorated.(40) The Moyaone residents who hesitated to support the use of scenic easements and the creation of the park did so because they were concerned about the rights of local farmers. One resident, Rhonda Hanson, recalled her father's conflicted feelings this way—

My Dad loved the rural character of the land but I also know that… his populist roots made him nervous about scenic easements and the idea of giving the federal government control of the land. I think it had to do with his own experience because Midwestern farmers didn't trust the federal government when it came to land. Too often they lost their land and I think that influenced his attitudes about it. It wasn't that he didn't want to preserve the rural character, but I think there was a level of distrust about what the government might do.(41) |

Beyond the individual loss of property, the movement to create the park could not help but transform the meaning and values associated with the landscape. During the conservation campaign, attention shifted away from the agricultural heritage of Accokeek towards the land's scenic value, transforming it from a dynamic cultural landscape into a static, idealized natural one. In the spring of 1963, five families hired a lawyer to prevent the National Park Service from acquiring their land. The lawsuit portrayed the Moyaone Association as profit-motivated real estate developers hiding behind a façade of conservation.(42) Their opposition attracted notice from Congress, and it temporarily slowed the progress of land acquisition for the park. Ultimately, it was no match for the coalition of preservation entities or congressional supporters. The MVLA repeatedly stressed the historic significance of the view, and they succeeded in generating letters of support from across the country. By January 1963, a majority of Moyaone residents had donated scenic easements to the Accokeek Foundation, successfully pushing forward the creation of the park.(43) The foundation eventually deeded the scenic easements to the Federal Government.(44)(Figures 4-5)

In the meantime, members of the Moyaone Association public affairs committee worked to change state law to enable local governments to provide tax incentives for the preservation of open space. Under the tax code of the State of Maryland, the value of land was determined by its development potential, not its actual use. Ironically, assessing land in this manner hurt farmers as well as historic preservationists because there was no incentive for maintaining open space or working the land. Moyaone Association members Belva Jensen and Dixie Otis made frequent trips to the state legislature in Maryland, educating politicians about the value of retaining open space and the potential use of scenic easements as a conservation tool. Prince George's County Delegate Raymond J. McDonough was so impressed by the presentation Jensen and Otis had made to the State House Ways and Means Committee that he reportedly told the Moyaone Association, "Send those ladies up to Annapolis often!"(45) Jensen and Otis found other allies, particularly State Senators Fred Wineland from Prince George's County, Gilbert Gude from Montgomery County, and John Thomas Parran from Charles County, who co-sponsored the bill that changed the state tax code in 1965 to allow property tax assessments to rest on actual use. The change in state law enabled a subsequent change in the county law. In 1966, Prince George's County became the first county in the nation to approve tax benefits for preservation, allowing landowners to claim a 50 percent deduction on land set aside for preservation.

The passage of Prince George's County's scenic easement legislation helped soothe tensions between farmers and members of the Moyaone by promising economic relief for conservation of the landscape. In 1966 and again in 1967, thanks to steady pressure from Frances Bolton, John Saylor, and others, appropriations finally reached the necessary level to create the park.(46) Their timing was impeccable. The passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 signaled a new national commitment to preservation and established guidelines for the protection of other historically significant vistas and landscapes.

The Evolving View from Here

Nearly 40 years after the dedication of Piscataway Park and 50 years after the creation of the Accokeek Foundation, some of the residents at the park's doorstep still express reservations. One resident noted that "On balance, I think the concept of the Moyaone was very good. I think it probably would have been some hodge-podge development down there, and we're getting developed enough… . But I'm still not sure about the park… . How many people really get to use it?"(47) The question is an important one, and is not simply about the number of visitors who take advantage of the park's hiking trails, historical performances, or student education programs. Rather, it forces people to re-examine the fundamental stories that continue to structure programming, development, and resource management in national parks and other protected areas.

Under the rubric of "The View from Here," the Accokeek Foundation has taken several important steps toward re-establishing and re-defining its role on a landscape that is simultaneously scenic, agricultural, residential, and historic. In 2006, the foundation reorganized all of its agricultural and land stewardship activities under the umbrella of "sustainability," making a commitment to serve as the region's premier demonstration area for sustainable practices in farming, gardening, and recreational use. The foundation is committed to representing a strong philosophical perspective on the value of small-scale farming. It has begun to participate actively in ongoing regional discussions about smart growth and green infrastructure development. It has begun to re-imagine its interpretive programming, focusing on aspects of Maryland's agricultural past that resonate and remain relevant today. It is continuing to develop ecological and historical programs for students. Furthermore, the foundation is exploring the possibility of expanding the operation of its Ecosystem Farm and Institute for Land Based Training to provide hands-on learning opportunities for both experienced farmers who wish to transition from tobacco to food-based agriculture and inexperienced farmers who wish to experiment with intensive, small-scale techniques.(48)

The Accokeek Foundation is also honoring the important work its founders accomplished in influencing preservation law in Maryland. The state has renewed its commitment to smart growth, and the Accokeek Foundation has the experience to participate in a meaningful dialog with professional planners at the state and county level. Closer to home, the foundation is encouraging residents of the Moyaone to work with the National Park Service to re-visit and update the terms of their relationship under the scenic easements.

The Accokeek Foundation has also taken steps to ensure that visitors and stakeholders are able to participate in conversations about the meanings and values that shape the cultural landscape. In June 2007, the foundation installed a series of interpretive signs. The signs help visitors recognize nature, history, and agriculture as interpretive frameworks, all of which actively create meaning on the park landscape. The signs also encourage visitors to participate in the evolution of a more sustainable infrastructure in the region. The foundation has also actively sought out new partnerships to encourage members of the Piscataway Nation, the African American community, and the remaining farming families to help ensure that their views are heard. As all of these projects and programs indicate, the Accokeek Foundation is working to ensure that Piscataway Park is not merely meaningful because it has preserved the view from Mount Vernon but also because it advocates a preservation vision that has relevance and resonance well beyond the park's boundaries.

About the Author

Denise D. Meringolo, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of history at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. From June 2006 to August 2007, she served as a scholar-in-residence at the Accokeek Foundation and continues to serve as a scholarly advisor to the foundation staff.

Notes

1. This article evolved out of research conducted for an exhibit to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Accokeek Foundation. The bulk of information came from the following collections: the records of the Accokeek Heritage Project, an oral history and local history project sponsored by the Maryland Humanities Council and conducted in conjunction with the Accokeek Foundation; the collections of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, particularly the Records of Operation Overview and the Frances Payne Bolton Papers, located in the Library and Special Collections Division of George Washington's Mount Vernon; the Accokeek Foundation Papers located in the Southern Maryland Studies Center, College of Southern Maryland; the collections of the Maryland Room at the Hyattsville Branch of the Prince George's County Public Library; the collections in the Library of the Prince George's County Historical Society; the collections of the Alice Ferguson Foundation as well as the Alice Ferguson Foundation website; archival collections located in the historian's office and library at the National Capital Parks-East Headquarters; a private collection of the Moyaone Reserve newsletter, Smoke Signals, held by Nancy Wagner; and the Moyaone Association Archives, a private collection maintained by the board of the Moyaone Association.

The author would also like to thank those who graciously shared their research, ideas, knowledge, and information: Scott and Dorothy Odell, who led the local history project from which "The View from Here" evolved; Wilton Corkern, Annmarie Buckley, Shane LaBrake, Matt Mulder, Laura Ford, Matt Mattingly, and all the staff of the Accokeek Foundation; Gayle Hazelwood, Kirsten Talken-Spaulding, Stephen Potter, Frank Faragasso, and everyone in the offices of National Capital Parks-East; George Hanssen, Belva Jensen, Nancy Wagner, Margaret Schmid, and Susan Jones of the Moyaone Reserve; and Jennifer Kittlaus and Barbara McMillan in the library at George Washington's Mount Vernon.

2. According to National Park Service guidelines, a cultural landscape is "a geographic area, including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein, associated with a historic event, activity, or person or exhibiting other cultural or aesthetic values." Piscataway Park fits the criteria for several reasons. It contains remnants of a 17th century settlement of the Piscataway people, historic fields and farms, and a landscape that developed through vernacular historical processes. For a useful summary of the criteria, see Charles A. Birnbaum, "Protecting Cultural Landscapes: Planning, Treatment and Management of Historic Landscapes," Preservation Brief 36 (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1994).

3. Paul Goeldner and Barry Mackintosh, "Piscataway Park," National Register nomination form, 1979. The copy to which this article refers is located at National Capital Parks-East Headquarters in the office of Frank Faragasso.

4. Isaac Weld, Travels through the States of North America, and the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, During the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797 (London, England: J. Stockdale, 1799). Weld's comment appears among a series of collected observations in the Operation Overlook Collection Library at George Washington's Mount Vernon.

5. Robert L. Stephenson, The Prehistoric Peoples of Accokeek Creek (1959) reprinted with Stephen Potter, A New Look at the Accokeek Creek Complex (Accokeek, Maryland: The Alice Ferguson Foundation, 1984).

6. Arthur Pierce Middleton, Tobacco Coast: A Maritime History of Chesapeake Bay in the Colonial Era (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 148.

7. A series of short articles developed for the county's tercentennial and now online give a useful summary of the history of Prince George's County, particularly the centrality of tobacco in the county's development. See "History of Prince George's County," http://www.pghistory.org/PG/index.html, accessed on September 8, 2007. The Colonial Williamsburg website (http://www.history.org/, accessed on September 8, 2007) features excellent discussions of colonial life and economics. The very basic description in this essay is indebted to the material on these sites and to the interpreter training materials produced by the Accokeek Foundation for its living history performers.

8. For more discussion on the migrations and warfare created by European settlement, see Jack Forbes, "The Renape People: A Brief Survey of Relationships and Migrations," Wicazo Sa Review 2 no. 1 (Spring 1986): 14-20.

9. Some of the largest plantation homes were absorbed into the city of Washington, DC, upon its establishment in 1790. John Michael Vlach has written and lectured widely on these and other plantations in Southern Maryland. See John Michael Vlach, "The Quest for a Capital," http://www.capitolhillhistory.org/lectures/vlach/index.html, accessed on September 8, 2007.

10. Ironically, the exodus restored a measure of stability to the population: The names of plantation owners that appear on 19th-century maps of Accokeek remained on land records and mailboxes well into the 20th century.

For more on the history of Maryland's tobacco culture, see, for example, T. H. Breen, Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of the Revolution (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1985); Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986); and Daniel Blake Smith, Inside the Great House: Planter Family Life in Eighteenth Century Chesapeake Society (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1980).

11. Bernie Wareham, interview by Scott Odell, February 12, 2002, Accokeek Heritage Project Archives, Accokeek, Maryland.

12. For a discussion on the construction of wilderness, see, for example, William Cronon, ed., Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1996); Mark David Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of National Parks (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Robert H. Keller and Michael F. Turek, American Indians and National Parks (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999).

13. Alice Leczinska Lowe Ferguson, Adventures in Southern Maryland, 1922-1940 (Washington, DC: National Capital Press, 1941).

14. For more on the suburbs, see Rosalynn Baxandall and Elizabeth Ewen, Picture Windows: How the Suburbs Happened (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2001); and Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987). It is interesting to note that anti-suburban sentiments also permeate the work of urban planners. See, for example, James Howard Kunstler, The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America's Man-Made Landscape, reprint edition (New York, New York: Free Press, 1994).

15. Baxandall and Ewen, Picture Windows.

16. The Greenbelt Town Program was a New Deal project designed to assist the poor in two ways: It hired the unemployed to perform necessary labor for clearing land and building suburban developments, and it provided housing to working families. The Greenbelt Program was administered under the Resettlement Administration and resulted in the construction of three towns: Greenbelt, Maryland; Greendale, Wisconsin; and Greenhills, Ohio. For more on Greenbelt, see Cathy D. Knepper, Greenbelt, Maryland: A Living Legacy of the New Deal (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001) and Mary Lou Williamson, ed., Greenbelt, History of a New Town, 1937-1987 (Virginia Beach, Virginia: The Donning Company Publishers, 1997).

17. For a detailed analysis of housing policy, see Gail Radford, Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1996). The creation of the Federal Housing Administration during the New Deal helped limit the risk of default on mortgage loans and changed dozens of state and federal laws to legalize long-term mortgages with low down payments. This trend made homeownership more accessible to many middle class Americans. Some legal historians argue that the expansion of homeownership had an unequal impact, however. See for example, Adam Gordon, "The Creation of Homeownership: How New Deal Changes in Banking Regulation Simultaneously Made Homeownership Accessible to Whites and Out of Reach for Blacks," The Yale Law Journal 115 no. 1 (2005).

18. Baxandall and Ewen, Picture Windows.

19. The post-war period saw the construction of Indian Head Highway and the Woodrow Wilson Bridge among other projects that made the Prince George's County area attractive for suburban development.

20. During the first two decades of its existence, the original group formed a number of companies and nonprofit organizations to manage the Moyaone. These were called the Moyaone Company, the Moyaone Association, and the Moyaone Reserve. Today, the development is called the Moyaone Reserve. This article uses the Moyaone Association and the Moyaone Reserve to describe the community.

21. William Harris, interview by Scott and Dorothy Odell, November 21, 2003, Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

22. It is challenging to unravel the history of these three institutions because the membership, boards, and staff overlapped, sometimes creating administrative conflict and often making it difficult to distinguish which entity was doing what work.

23. E. Lee Fairley, interview by Scott and Dorothy Odell, February 16, 2002, The Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

24. William Harris, interview by Scott and Dorothy Odell, November 21, 2003, The Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

25. Some historical documents at the Prince George's County Historical Society record a Clagget family, but those who live in Accokeek today generally spell their name "Clagett."

26. Manning Clagett, interview by Ann Chab and Scott Odell, June 11, 2003, Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

27. The Washington Star, August 27, 1956, newspaper clipping, binder 1, Operation Overview Collection, Collections of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia.

28. Interestingly, there was a proposal—strongly opposed by the Moyaone Reserve—to create a Maryland loop for the parkway along the Maryland shoreline. Wall was encouraged to learn that the National Park Service's master plans included a discussion of the importance of views and vistas in landscape design. However, without a congressional mandate and significant appropriation for the purchase of private property, the agency could not act with sufficient speed.

29. The notes are located in folder 2, box 1, Archives of Operation Overview, Mount Vernon.

30. The letter is located in folder 2, box 1, Archives of Operation Overview, Mount Vernon.

31. Those interested parties included the Alice Ferguson Foundation, the Moyaone Association, the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, the National Park Service, and the Smithsonian Institution. The details are based on the recollections of Robert Ware Straus and published in his memoir, The Possible Dream: Saving George Washington's View (Accokeek, Maryland: The Accokeek Foundation, 1988).

32. The Accokeek Foundation went to work immediately, developing a program of land management designed to document the scientific value of the Maryland shoreline. The foundation's earliest projects included plans for a colonial farm demonstration area and a genetic study of native crops.

33. The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission was created by the Maryland State Legislature in 1927 to "develop and operate public park systems and provide land use planning for the physical development of the great majority of Montgomery and Prince George's Counties," bordering the District of Columbia. "M-NCPPC," http://www.mncppc.org/, accessed on September 4, 2007.

34. Nancy McLaughlin, "Conservation Easements—A Troubled Adolescence," Journal of Land Resources and Environmental Literature 26 no. 1 (2005): 47-56. The National Park Service had been using scenic easements since the late 1930s to protect views from historic parkways such as the Blue Ridge Parkway. However, the concept was not widely recognized until the late 1950s, when the journalist William Whyte described the usefulness of a "conservation easement."

35. Newspaper clipping, binder 1, Operation Overview Collection, Mount Vernon. The commission was impressed by the show of opposition, but it was also interested in the economic benefits that might come from development. It ordered a study of alternative sites for the plant, and the WSSC did not formally give up its interest in the property until after the establishment of the park. Newspaper clippings in the binders of Operation Overlook indicate that conservationists were still wrangling with the WSSC until the late 1960s.

36. It took nearly 10 years and a concerted public relations effort to acquire enough land to establish Piscataway Park. Public laws authorizing the establishment and increasing the acreage for Piscataway Park were passed on October 4, 1961, July 19, 1966, and October 23, 1972. Hervey Machen, a member of the Maryland General Assembly's House of Delegates in 1961, was elected to Congress in 1964 and proved to be an important supporter of the park throughout this process. For a more detailed and personal administrative history of the creation of Piscataway Park, see Robert Ware Straus and Elinor B. Straus, The Possible Dream: Saving George Washington's View (Accokeek, Maryland: The Accokeek Foundation, 1988). Additional research in the papers of Frances Payne Bolton will reveal more about the ways in which her relationships with environmentalists in Congress helped foster the development of the park.

37. The Accokeek Foundation, which represented the interests of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association and residents of Moyaone, sought to retain some control over land use. Over the course of nearly three years, the Accokeek Foundation and the National Park Service, which had little experience sharing land management responsibilities, hammered out the terms of a public-private partnership that enabled the foundation to operate programs and steward 200 acres of land in Piscataway Park. One such program is National Colonial Farm, a living history museum established in 1958 that depicts a Maryland family farm on the eve of the American Revolution. The agreement is still in place and is subject to renewal every 20 years.

Most of the park's supporters, staffers, and neighbors insist that the Accokeek Foundation-Piscataway Park management agreement was "the first" such agreement in the National Park Service. This aspect of administrative history requires further research.

38. Dixie Otis, interview by Susan Thompson and Milburn Butler, February 9, 2002, The Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

39. Newspaper clipping, binder 1, Operation Overview Collection, Mount Vernon.

40. At least 12 families sent letters to the easement committee, strongly opposing scenic easements and flatly refusing to support any plan that might infringe on their property rights. One opponent wrote—

I wish to state that I am not in favor of having easements on my farm or property and definitely will not donate such easements to the Federal Government. Furthermore, if certain members of the Moyaone Association wish to donate easements to the Federal Government, let them do so. However, the Moyaone Association should not be overstepping its boundaries and dictate to the other landowners in this area what should be done to their land. |

This excerpt was taken from a handwritten note collected by the Accokeek Heritage Project and located in the privately held project archives.

41. Rhonda Hanson, interview by Nancy Wagner and Susan Hoffman, February 28, 2004, The Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

42. "Farmers Ask Congress to Block US Purchase of Their Land," The Washington Post, March 21, 1963.

43. A gap of several years separated the enabling legislation, the creation of a public-private management strategy for Piscataway Park, and the establishment of the park. The National Park Service now holds the easements and monitors compliance.

44. For a complete list of restricted activities and full conditions, visit http://www.moyaone.org/easements.php, accessed on September 8, 2007.

45. Nancy Wagner, [untitled], Smoke Signals (Moyaone Association newsletter), February 4, 1965.

46. Between 1961 and 1968, appropriations for the park were written into various pieces of legislation and then cut or reduced. A Congressman from Ohio briefly opposed the park because he felt it was more appropriately a state or county project. The farmers' protest also temporarily stalled appropriations. A politically connected and wealthy individual bought the Marshall Hall property and proposed to build an amusement park with an American history theme. Park supporters capitalized on President Lyndon Johnson's commitment to beautification and his particular interest in conservation along the Potomac River, which he announced in 1964. The owner of Marshall Hall eventually accepted a buyout.

47. Daniel Dyer, interview by Ann Chab and Scott Odell, June 18, 2003, The Accokeek Heritage Project Archives.

48. Wilton Corkern, Annmarie Buckley, Shane LaBrake, Matt Mulder, and Laura Ford, "Accokeek Foundation, 50th Anniversary Initiative Strategic Vision," February 11, 2006, internal memorandum approved by the Board of Directors.