Viewpoint

Making Archeological Sites: Experience or Interpretation?

by Frank Matero

Any consideration on the topic of aesthetics and preservation as applied to archeological sites demands reflection on three critical questions:

How should we experience a site, especially one that is fragmented and possibly illegible?

How does intervention affect what we see, what we feel, and what we know?

How can display promote an effective and active dialog between past and present?

All preservation is a critical act that results in the conscious production of "heritage." As an activity of mediation between the past and the present, conservation is ultimately responsible for what the viewer sees, experiences, and can know about the past. Much contemporary practice is concerned with finding an acceptable balance between protecting the historical and documentary values inherent in the physical form and fabric, including evidence of age through weathering, with the aesthetic values implicit in the original work including its flaws and subsequent alterations. Such questions have been fundamental to preservation theory and practice concerned with interventions in the life of a building or site regardless of age. The tension inherent in this dialectic defines the very nature of conservation as the push-and-pull between the emotional and humanistic on the one hand, and the rational and scientific, on the other. Fitch attempted to explain and guide such intervention policies through a triadic model based on three tangible aspects:

The "present physiognomy" of the building/site (accumulated physical evidence including age-what Ruskin called "voicefulness")

The "architectonic or aesthetic integrity" of the building/site in purely formal terms (original artistic aesthetic intent or what Viollet-le-Duc termed "stylistic unity")

The "phylogeny and morphogenetic development of the artifact across time" (the development of type and structure over time, each work being unique and individual unto itself)(1)

Archeological Sites

At least since the 18th-century excavations of Pompeii, archeological sites have long been a part of heritage and tourism, certainly before the use of the term "heritage" and the formal study of tourism. Archeological sites exist in a state rarely imagined by their makers. Their state of fragmentation, dereliction, and abandonment are heavily modified through practices of excavation and presentation—the latter to reveal and give readings of history and experience through modes of display. Interpretation and display begin together at the moment of excavation. Historically, archeology has long been preoccupied with finds and later with facts. The anticipation of preservation and display as an integral part of the archeological project began in the 18th century with the belief in and contemplation of nature and the solace that could be derived from a ruin. There was no question of preservation in the Romantic or Picturesque attitude towards a ruin.(2) The ruin was there to stimulate the visitor, the effect sometimes enhanced by selective destruction and cultivated vegetation. The pleasure to be derived was one of reconstruction in the mind's eye of the ancient place in its original state. The better one understood the ruin, the better the imaginative reconstruction.

It was in the late 19th century that the first formal attempts to both excavate and display in a scientific manner were attempted at excavations such as Assos (Turkey), Knossus (Crete), and Casa Grande (Arizona). Like other heritage sites, the conservation of ruins requires the removal or mitigation of deterioration; however, the very nature of their fragmented disposition also determines and affects their meaning and character. This has a direct and powerful effect on visual legibility and indirectly conditions our perceptions and notions of authenticity.

Among the repertoire of conservation techniques often applied to archeological sites are structural stabilization, anastylosis, reconstruction, protective shelters and reburial, and a myriad of fabric-based conservation methods. Each solution affects the way archeological information is preserved and how the site is experienced, transmitted, and therefore understood, resulting in competing scientific, historic, and aesthetic values. However technological study and critical definition of the site constitute only the point of departure for conservation. It is the archeologist in consultation with stakeholders who generally develops the narratives and it is the conservation professional who determines how that narrative will be played out on-site, therefore dialogue and negotiation are tantamount to a successful project.

Archeological sites are what they are by virtue of the disciplines that study them. They are made, not found, formed over time, through destruction, abandonment, excavation, and preservation. Display as intervention is an interface that mediates and transforms, and conservation's methods have always been a part of that process.

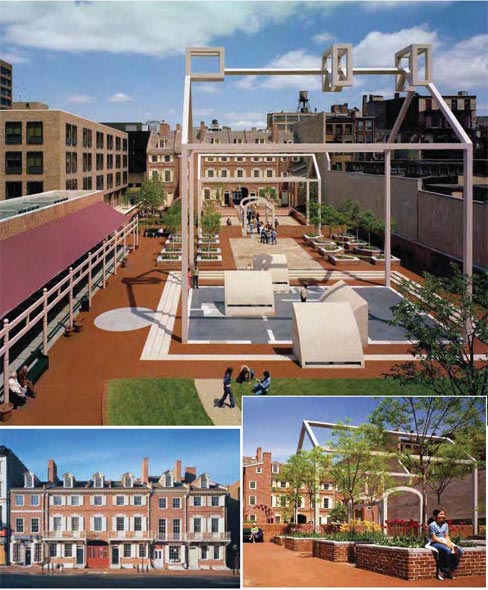

At Franklin Court, the site of Benjamin Franklin's House in Philadelphia and part of Independence National Historical Park, a team of designers, engineers, and archeologists offered a revolutionary solution during America's Bicentennial in 1976 by revealing the site's historical and aesthetic authenticities through real and exaggerated elements. (Figure 1) The result was the construction of a spatial montage that never confuses the present with the past yet allows visitors an open-ended experience of history, memory, and time. Earlier plans in the 1950s to celebrate Franklin on the site of his house included building a memorial park or architectural reconstruction. They were rejected despite the use of both approaches within the National Park Service and the nation in general since the 1920s.

|

Figure 1. Franklin Court, Independence National Historical Park, 1976. (Courtesy of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, architects.) |

The alternative solution proved that didactic interpretation and somatic experience could be achieved together through the skillful combination and display of above- and below-ground archeology as well as reconstruction, two and three-dimensional historic space as a hidden urban court and garden, an abstract house plan and volume (the famous "ghost structure"), and a multimedia underground museum. The brilliance and success of the design solution lay not only in the diversity, placement, and juxtaposition of the site's interpretive components (both archeological remains and "interpreted" features) but in the recognition that the original hidden enclave setting of the Franklin site could offer up a powerful experience that brought time and space together in an urban oasis appreciated in Franklin's time as well. Fitch pronounced Franklin Court "…from an aesthetic point of view, the most successful of all [archaeological sites]… marking a new level of maturity in American preservation activities."(3)

Experience or Interpretation?

The last century's obsession with artistic unity, style, and connoisseurship in the preservation of the visual arts planted the seeds for a revolution of intangible content and process over tangible form. But the question now is: are we losing the desire and ability to respond to the physicality of things and places, to see more, hear more and feel more, in deference to the aggressive revealing of invisible content at the expense of the physical place? As Susan Sontag warned in 1964, "Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art…interpretation tames art by reducing it to its content…and makes it manageable, comfortable."(4) Here Sontag recalls Hegel's problems with the analytical zeal of "Understanding" upon "Beauty" when he wrote, "Beauty, powerless and helpless, hates understanding, because the latter exacts from it what it cannot perform."(5)

Of course interpretation can offer up a complex reading that has the ability to reveal much about a site that is invisible; it offers another form of excavation that completes what the trowel has revealed or left behind. But then so can a site's inherited physical presence transport the viewer out of time through a series of experiential sensory stimuli. In an effort to develop all-informing narratives, we revise, revamp, reveal, and expose, littering places with commentary in the form of interpretive infrastructure: information centers (no longer museums), signs, viewing platforms, protective shelters, digital technology, and shops and cafes. Instead, to paraphrase Sontag, shouldn't our ultimate task be to show how it is what it is, rather than to show what it means?

Conclusion

Like all disciplines and fields, archeological site conservation has been shaped by its historical habit and by contemporary concerns. What began as a long-lived European tradition of cultivating a taste for ruins and the picturesque, has developed into the protection of the whole place rather than simply artifact conservation or the removal of a site's architectural features, the Parthenon marbles being among the most egregious examples. Despite the level of intervention, specific sites—namely, those possessing monumental masonry remains—have tended to establish an idealized approach for the interpretation of archeological sites in general. However, many sites such as the earthen mound settlements of the ancient Near East at once challenge these ingrained notions of ordered chaos and arranged masonry by virtue of their fragile materials, and temporal and spatial disposition, while living ancestral sites such as Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon in the American Southwest reveal very different worldviews, sometimes resulting in conflicting relationships between professionals and traditional communities. Moreover, changing notions of "irresistible decay" have expanded and challenged the realm of what is to be considered, interpreted, and preserved as a ruin, as Philip Johnson himself pronounced on seeing his own 1964 New York State Pavilion transform into a sublime wreck.(6)(Figure 2) Archeological sites, like all places of human activity, are constructed. Despite their fragmentation, they are complex creations that depend on the legibility and perceived authenticity of their components for meaning and appreciation. Yet they are also places that possess the power to remember, to admonish, and to elicit strong emotions. How the interpretation and display of such places are realized remains the challenge for the professional in shaping what we see, how we feel, and what we know.

|

Figure 2. New York State Pavilion, Queens, New York, 2008. (Courtesy of the author.) |

About the Author

Frank Matero is Professor of Architecture and former Chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the School of Design, University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennyslvania. He may be contacted at fgmatero@design.upenn.edu.

Notes

1. James Marston Fitch, Historic Preservation: Curatorial Management of the Built World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1990), 83-84.

2. While the basic definition of a ruin has remained fairly constant throughout recorded history, associated meanings and values have not. Ruins are the remains of human-made architecture: structures that were once complete, as time went by, have fallen into a state of partial or complete disrepair, due to lack of maintenance or deliberate acts of destruction. Natural disaster, war and depopulation are the most common root causes, with many structures becoming progressively derelict over time due to long-term weathering and scavenging. (Definition available online at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruin, accessed on June 29, 2010).

3. Fitch, 303.

4. Susan Sontag, "Against Interpretation," in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966), 7-8.

5. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Phenomenology of Mind, quoted in Speaking of Beauty by Denis Donoghue (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003), 24.

6. Philip Johnson, The Architecture of Philip Johnson (Houston: Anchorage Press, 2002), 2.