Research Report

The Historic American Engineering Record's Maritime Documentation Project

by Brian Clayton

The United States Maritime Administration (MARAD) maintains a fleet of inactive ships in anchorages in James River, Virginia; Beaumont, Texas; and Suisun Bay, California.(Figure 1) From vintage World War II craft to modern cargo ships, this "mothball" or "ghost" fleet dates back to 1946, when Congress established the National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) as an emergency supply of ships in time of crisis.(1) Within the fleet, MARAD also maintains many ships that have outlived their military usefulness and await disposal.(2)

The National Park Service's Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) visited the three reserve fleet sites in 2006 to document four ships: the fleet oiler Taluga, tankers Mission Santa Ynez and Saugatuck, and the troopship Private Frederick C. Murphy. Built during World War II, the ships have lain dormant for many years and weathered in their flotillas yet offer a great deal of information about their design, operational details, and histories.(3)

The focus of the recording effort at James River was a T2-SE-A1 tanker, Saugatuck, built by Sun Shipbuilding and Drydock Company in Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1942. The U.S. Maritime Commission's World War II Emergency Program constructed 481 tankers in this class, for many years the workhorses for the U.S. Navy. The Saugatuck served the Navy on and off for 31 years as an auxiliary tanker and returned to the NDRF to stay in 1974. Her paint was worn and rusted, but she remained largely intact. Later, the ship developed leaks and required constant monitoring. MARAD disposed of the Saugatuck at the end of 2006.(4)

At the second NDRF fleet in the Neches River, just south of Beaumont, Texas, the team documented the troopship Private Frederick C. Murphy (formerly SS Maritime Victory) built by Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1945. Although architects originally designed the Maritime Victory as a VC2-S-AP2 cargo ship, the U.S. Maritime Commission converted it to a troopship in the summer of 1945, adding "pipe racks" (bunks) within its cargo holds to accommodate 1,597 troops.(Figure 2) War planners converted 97 other Victory ships as part of an invasion fleet for an assault on the Japanese home islands.(5) After the war, the War Shipping Administration used the Maritime Victory to repatriate American servicemen from Europe. In 1947, the U.S. Army acquired the ship and renamed it the Private Frederick C. Murphy after a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient from World War II. The Army briefly used the ship and in 1950 returned it to the reserve fleet, where it remained for 56 years before MARAD scrapped it.(6)

Suisun Bay, home of the third NDRF fleet, is nestled between the foothills of Benicia and Martinez, California. There, the HAER team recorded two ships, the Mission Santa Ynez and the Taluga. The Marinship Corporation in Sausalito, California, constructed the Mission Santa Ynez in 1943, and Bethlehem Steel in Sparrows Point, near Baltimore, Maryland, built the Taluga in 1944.(7) Architects designed the Mission Santa Ynez as a T2-SE-A2 tanker.(8) She served the Navy for 32 years and became part of the reserve fleet in 1975.(9) The Taluga was a T3-S2-A1 fleet oiler and served the Navy for 38 years. The oiler is noteworthy because it was a test platform for a civilian-manned crew to work within the Military Sealift Command, the administrator of shipping for the Navy. The pilot program was a success, and the crew set the standard for all civilian manned naval auxiliaries. After decommissioning, the Taluga retired to the NDRF in 1982. Both vessels are on donation holds because of expressions of interest in using them as historic ship exhibits.(10)

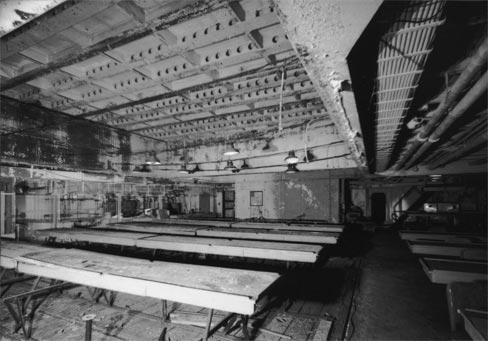

The ships HAER recorded provide valuable insight into shipboard living conditions. The most fascinating vessel was the Private Frederick C. Murphy, which contained a majority of her original furniture and equipment, including the "pipe rack" bunks, mess tables, and heads (bathrooms)(Figure 3). Bakery ovens, reefers (large refrigerated rooms), and other cooking equipment and food storage areas remained in place. The reefers still had the strong scent of fresh pine inside their wooden lockers.(11)

|

Figure 3. The mess deck of the troopship Private Frederick C. Murphy, photographed in 2006, has not changed much since 1945. (Photograph by Jet Lowe, courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

The HAER recording team had to overcome a number of obstacles at each location, the biggest of which was the lack of lighting. The reserve fleets run power to the rows of ships, but mainly for high water alarms and pumps. Jet Lowe, HAER photographer, applied his years of experience in low light settings to capture most of the interior photographs through a portable flash in lieu of floodlights. Every ship contained some sort of hazardous material, and the dilapidated vessels themselves posed risks, such as weak spots in the decks.(12)

Each reserve fleet has a skeleton crew of electricians and deck personnel to look after the ships (52 ships in the James River, 38 in Beaumont, and 73 in Suisun Bay, not including those "outported" or in MARAD custody but owned by other government programs). The crews scour the ships each day for problems, a daunting task considering that the ships average 500 feet in length and have multiple interior decks. All of the ships use cathodic protection to prevent their hulls from deteriorating below the water line; some vessels deemed militarily useful get dehumidifiers to protect their interiors.(13) In 1950, the NDRF fleet included 2,277 ships. Due to attrition, only 230 ships remain, 134 of which are held in "non-retention" status.(14)

Even if they have outlived their usefulness in times of national emergency, the vessels are still desirable. Ten states, for example, have turned 51 ships into artificial reefs, while others have become museum exhibits. MARAD discharges most of the obsolete vessels to recycling companies.(15) In today's metal market, premium steel (steel with a high nickel content) entices recyclers to bid competitively for the ships.(16) Since this initial project, HAER has arranged with the U.S. Coast Guard and MARAD to record 19 more vessels (3 Coast Guard cutters, and 16 additional ships) in the NDRF fleet.

About the Author

Brian Clayton is a National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers employee working for the Historic American Engineering Record in Washington, DC.

Notes

1. The fleet has been activated for seven wars since 1946.

2. L.A. Sawyer and W.H. Mitchell, Victory Ships and Tankers: The History of the 'Victory' Type Cargo Ships and of the Tankers Built in the United States of America during World War II (Cambridge, MD: Cornell Maritime Press, Inc., 1974), 28. MARAD maintains strict standards for ships slated for disposal—

All of MARAD's obsolete vessels are subject to the requirements of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), which requires a historic assessment process to determine if they possess historic value and are eligible for placement on [sic] the National Register. Not all of MARAD's obsolete ships have completed the historic assessment. |

See https://voa.marad.dot.gov/programs/ship_disposal/standing_quot/docs/DTMA1Q05006%20-%20FY05_Ship%20Disposa.pdf, accessed May 25, 2007.

3. HAER maritime documentation closely follows the initial documentation done in the 1930s by the Smithsonian Institution's Historic American Merchant Marine Survey (HAMMS).

4. Sawyer, 89, 97; U.S. Navy, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, volume VI (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1991), 110-15; site visit, April 2006; Susan Clark, MARAD Public Affairs Officer, personal communication. The Saugatuck was a high priority vessel scheduled for disposal due to her deteriorated state and the environmental threat she posed to the Commonwealth of Virginia. See Acting Maritime Administrator's comments at http://www.marad.dot.gov/Headlines/newsletters/April_2005/April_2005_Newsletter.pdf, accessed May 20, 2007.

5. That assault never took place—Japan surrendered to the United States following the atomic bombing of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

6. Sawyer, 23-24, 42. ESCO Marine, Inc., won the bid to dismantle the Private Frederick C. Murphy.

7. Walter W. Jaffe, The Last Mission Tanker (Sausalito, CA: Scope Publishing, 1990), 14; U.S. Navy, Ships' Data U.S. Naval Vessels: Auxiliary, District Craft and Unclassified Vessels (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1945), 181.

8. The Mission Santa Ynez was very similar to the Saugatuck but modified with a larger engine (10,000 versus 6,000 horsepower).

9. Jaffe, Mission Tanker, pp. 12, 72.

10. U.S. Navy, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, volume VII (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1991), 25-27; Sawyer, 171; Susan Clark, MARAD Public Affairs Officer, personal communication.

11. Site visit, March 2006. The reefers also had traces of asbestos.

12. Site visits, January-April 2006. Hazardous materials included asbestos, PCBs, and lead paint. The team had to follow specific health and safety instructions and use respirators on some of the vessels. Two escorts accompanied the recording team at all times.

13. Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary defines cathodic protection as "the prevention of electrolytic corrosion of a usually metallic structure…by causing it to act as the cathode rather than as the anode of an electrochemical cell," http://mw1.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cathodic%20protection, accessed May 20, 2007.

14. Many vessels were sold to foreign companies for scrapping, until 1994 when the United States Environmental Protection Agency raised concerns about the transfer of hazardous material outside the United States. Since 1995, MARAD has refrained from selling ships overseas. Sawyer, 28; site visits, January-April 2006; The National Defense Reserve Fleet Inventory is available online at http://www.marad.dot.gov/offices/ship/Current_Inventory.pdf, accessed July 10, 2007.

15. MARAD pays for the scrapping because of the high costs of disposal of on-board contaminants.

16. U.S. Department of Transportation: Maritime Administration, "National Defense Reserve Fleet," http://www.marad.dot.gov/Offices/Ship/PRESS_NDRF_Current.pdf, accessed February 6, 2007.