Last updated: February 2, 2024

Article

National Park Getaway: Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

NPS Photo

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) is recognized as the founder of American landscape architecture as well as “America’s Parkmaker." In 1883, after supervising the design and construction of such landmarks as Central Park and the US Capitol Grounds, Olmsted moved his family from New York City to 99 Warren Street in Brookline, Massachusetts. Besides being a home for his family, “Fairsted,” as Olmsted named his estate, was where he, his sons, and associates created the world's first full-scale office for the practice of landscape architecture.

The initial workspace Olmsted used was the parlor of the 1810 house he had purchased. His son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., remarked, “His office always looked like it was—part of his home comfortably adapted for office use.” This room would remain the senior partners’ office, whether they were an Olmsted or not. But it was clear from the beginning that more space would be needed. Building out from the North Parlor, a rambling office wing was added and became workspace for more than 60 employees. At their height the firms could be working on 150–200 active projects—from 500 acre public parks to intimate private gardens.

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site Collection

In business for more than a century, the Olmsted firm also served as a model for the nascent profession of landscape architecture. How do you create a system that will allow the designer’s intangible idea to take form as a real landscape that could be a continent away? How do you take something from pencil to park? One step in that process was documentation.

Over its years in business, the firm amassed a collection of 66,000 photographs documenting some of the 6,000 projects they worked on across North America (in 47 of the 50 states!). Oftentimes spanning decades, they reflect the fact that unlike architecture, the landscape envisioned by the designer may take decades to grow into existence. So a 25-year old apprentice with a Kodak Brownie camera might return as firm partner with his Instamatic, taking one last look at his handiwork before he retires.

NPS Photo

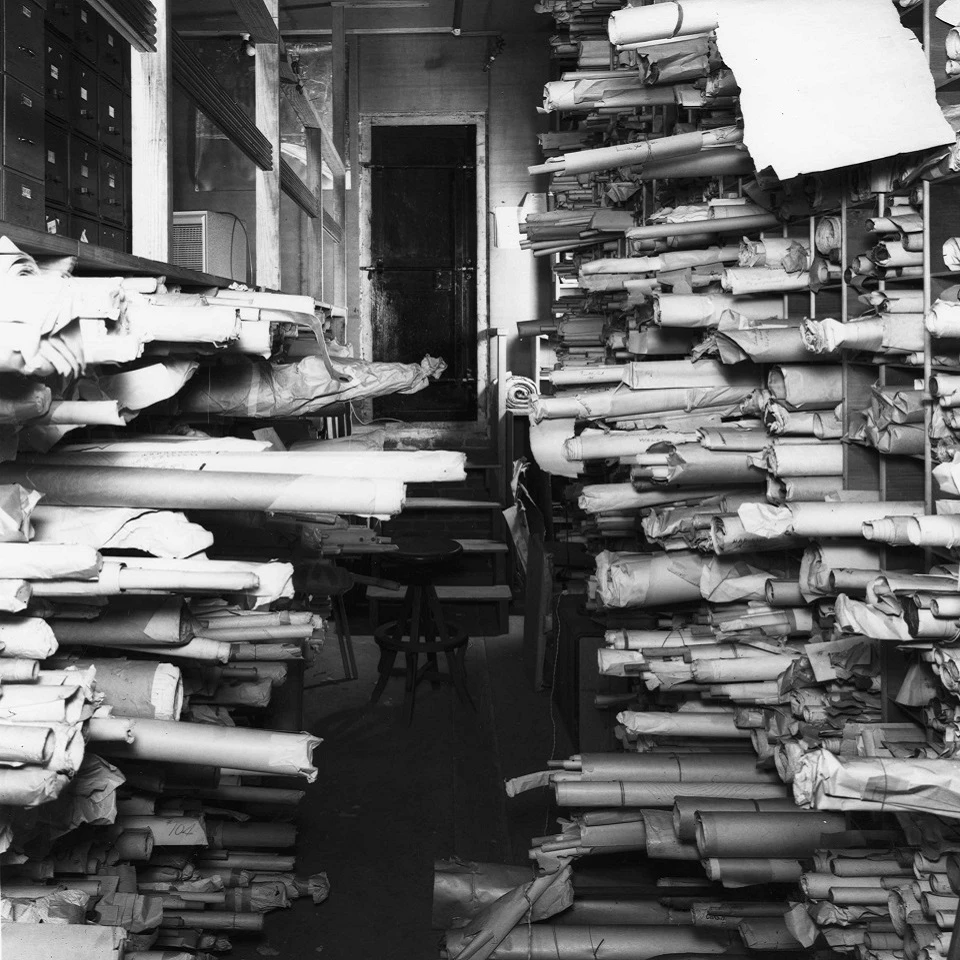

Although photography was an important activity, it was the production, reproduction, shipping, and storage of plans that drove almost all day-to-day activities. Creating a built landscape often meant producing hundreds of plans—from the broadest concepts to the smallest detail. Franklin Park in Boston has one "general plan" showing what the landscape should look like at completion and over 700 "working drawings" showing what you needed to do to get there. And like photos, many plans show long periods of involvement. Olmsted’s son noted that some projects “reactivate” from time to time. Today the Olmsted Archives contain approximately 140,000 plans and drawings and as much a resource to today’s researcher who may be looking to restore a landscape as they were to the Olmsteds who were helping create them.

Now you could not expect to visit here without experiencing a genuine Olmsted landscape—and you will not be left disappointed. Although less than 2 acres, the Fairsted landscape is in some ways a domesticated version of a public park—a city park on a family scale. As you enter beneath a spruce-pole arch, the “Hollow,” a small sunken garden, is immediately on your right. Look closer and you’ll find roughhewn stone stairs that take you from the wider world into your own space below, blocking out the world both visually and aurally.

NPS / Geoffrey Brahmer

But if solitude is not your thing, take a left as you as you enter and find the path into the Rock Garden. As you walk, you’ll be surrounded by broad-leaved mountain laurel and the smell of hay-scented ferns—scenery “close to the eye” as Olmsted put it. Then a gentle curve to the right finds you standing in a sundrenched rolling swath of green known as the South Lawn. To expand the sense of space, Olmsted planted trees and shrubs to obscure any view of boundaries between the South Lawn and the surrounding properties. This allowed him to “borrow the view” of the larger estates surrounding him.

We hope you’ll come experience the Olmsted landscape yourself. It is open dawn to dusk year-round. Tours of the design office are available by advance reservation during the winter season. Can't make it in person? Explore the park virtually.

Researching in the Archives

Left image

Plans Vault in 1980

Credit: (NPS Photo)

Right image

Plans Vault today

Credit: (NPS Photo)