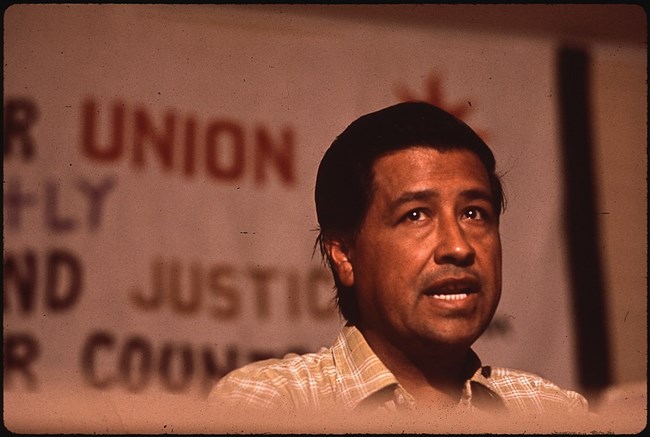

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: César Chávez.

Article

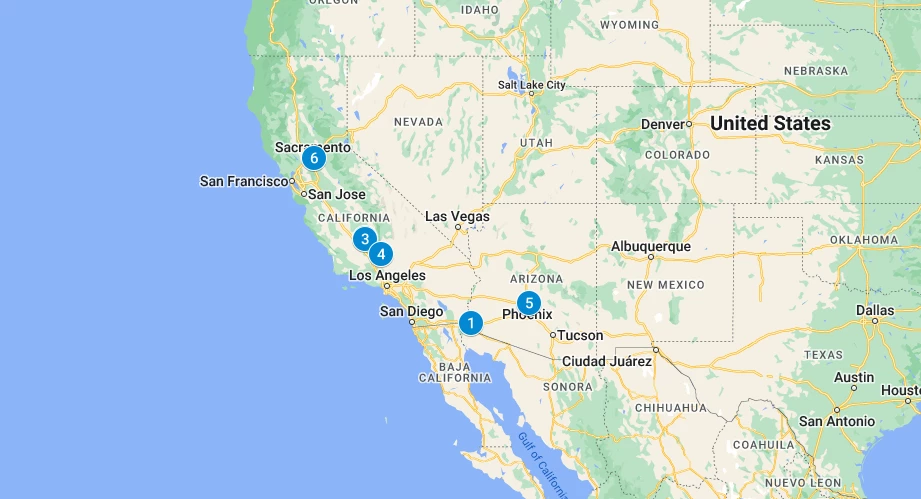

Places of Cesar Chavez

"Once social change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot un-educate the person who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore."

— Cesar Chavez, Address to the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco, Nov. 9, 1984

Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. This photo was provided by the National Archives and Records Administration as part of a cooperation project with Wikimedia Commons.

While African Americans were fighting for their Civil Rights in the 1960s, Cesar Chavez organized Latino and Filipino farm workers to do the same. Using similar tactics, including marches and boycotts, Chavez and his team brought crucial awareness to the working conditions and precarious living of the people who grow and harvest our food.

Cesar Chavez was born March 31, 1927, on his family’s small farm outside of Yuma, Arizona. His family lost their land in the Great Depression. Chavez joined them as a migrant farm worker after completing the 8th grade. He worked on farms throughout California, experiencing the challenging working conditions.

He first worked in political organizing with Fred Ross and a Latino Civil Rights group, the Community Service Organization (CSO). Chavez helped organize voter registration drives and anti-discrimination campaigns. In the CSO, he learned organizing principles. But Chavez wanted to focus on the rights of farm workers.

Despite widespread skepticism, he resigned from CSO and founded the National Farm Workers Association, which became the United Farm Workers. Their first major action in 1966 was to join Filipino organizers like Larry Itliong for the march from Delano to Sacramento, California in 1966 and an international grape boycott. Chávez would go on three 25-36 day fasts to further raise awareness, inspired by Mahatma Gandhi. Chavez passed away in Yuma, Arizona in 1993, while visiting to support local farm workers being sued by big agriculture.

Discover the places where Chavez lived, worked, and organized to better understand how he shaped economic and social change in the 20th century.

NPS Photo

1. Yuma Arizona

Cesar Chavez was born just outside of Yuma, Arizona in a small adobe home on March 31, 1927. His family moved to California when he was 11, after being forced off the family homestead during the Great Depression. The move away from Yuma started Chávez’ time experiencing the hardships of migrant farm work, both for his family and himself.

Chavez also died near Yuma in the village of San Luis on April 23, 1993. He was there helping the UFW defend a lawsuit brought by a large vegetable producer against farm workers. Even after successful strikes and boycotts, the UFW had to fight on a state by state basis for recognition and rights. In this case, the business sued the union for lost profits during the strike. But striking is a key way of demonstrating collective power for workers and Chavez wanted to support members during this challenge.

The city of Yuma, Arizona is a Certified Local Government.

© Harvey Richards Media Archive

2. Filipino Community Hall (Delano, CA)

Chavez’s efforts to form a union were not the first attempts to organize farm workers. Previous strikes had been broken by the lack of racial solidarity between farm workers when agriculture corporations brought in replacement workers from different backgrounds. In 1965, 1,500 Filipino farm workers in the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), led by Larry Itliong and others, organized in Delano to strike for better pay and working conditions. The vote took place on September 7, 1965, in Filipino Community Hall.

A few days after the vote, Itliong asked Chavez and the mostly Latino National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) to join the strike. While Chávez and other leaders initially felt the organization was too new for a risky strike, they would not undermine their fellow workers. The NFWA ended up adding vineyards to the sites targeted by the strike.

Filipino Community Hall became the site of strike for both unions. Even before the two unions merged in 1966, they met together and set up a communal kitchen to support each other. In 1966, the two unions formed the United Farm Workers (UFW) with Chavez as President and Itliong as Vice President. Leaders from other unions like the United Auto Workers, civil rights groups like SNCC and CORE, and prominent politicians like Senator Robert F. Kennedy came to Delano to support the strike. The strike led to other political actions like a national grape boycott. Filipino Community Hall is a site of solidarity and historic interracial cooperation.

NPS Photo

3. The Forty Acers

Chavez was committed to a union that supported farm workers on multiple levels. The United Farm Workers (UFW), formed in 1966, moved their Organizing Committee headquarters to Forty Acres in 1968, three years into their strike against grape growers. The National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) purchased the empty land in 1966 to set up a farmworkers’ service center. The goal was not only to have a place for political meetings but to provide goods and services to Filipino and Latino farm workers. Chavez helped set up a co-op gas station, health clinic, daycare center, and the Paolo Agbayani Retirement Village for older Filipino men, who did not have families in the U.S. because of immigration policies which prevented Asian legal residents from having family members join them. All the buildings, constructed in the 1960s and 1970s, were completed by volunteer labor.

Chavez used the Forty Acres gas station as the site of his first 25-day fast. Fasting was a non-violent technique Chavez learned from studying the work of Mahatma Gandhi. Staying in a windowless room in the newly completed structure, Chavez only left to walk to a daily Mass. The hunger strike drew national attention. Supporters came by the hundreds to Forty Acres to camp outside the gas station and show their support.

Forty Acres was the site where the first successful contracts by UFW were negotiated and signed. These contracts improved wages and working conditions and affirmed the agricultural unions’ right to bargain on behalf of more than 70,000 farm workers. When Chavez and the UFW moved their national headquarters again in 1971, Forty Acres continued to function as a service area and field station. It is widely considered a model for other UFW sites.

Chavez also held his longest fast in a room at Paolo Agbayani Retirement Village in 1988. He fasted for 36 days to protest the use of pesticides that poisoned workers and their children. When Chavez ended his fast, celebrities and activists continued it to raise further awareness.

Forty Acres is designated as a National Historic Landmark.

© Sujata King

4. Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz NHL/Cesar Chavez National Monument (Keene, CA)

La Paz is symbolic of UFW's transition beyond just grape workers in California to agricultural workers across the country. Chavez and the UFW moved their headquarters to this site in the Tehachapi Mountains in [1972]. North of Keene, California, the 180-acre site was originally a rock quarry, then a sanitarium for patients with Tuberculosis from 1917-1967. The state wouldn’t sell the property to UFW, so a wealthy movie producer who supported the movement put in the bid.

When Chavez and UFW moved onto the property in 1970, it already had buildings that served as dormitories, medical facilities, schools, and administrative buildings. Chavez named the site Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz, or “Our Lady, Queen of Peace.” It is commonly referred to as “La Paz” by farmworkers and union organizers.

Affiliated with the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organization (AFL-CIO), the UFW used its headquarters at La Paz to plan national labor campaigns, including a lettuce boycott and work to pass legislation like the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975. This was the first law to give agricultural labor unions bargaining rights.

Upwards of 200 people lived at La Paz at any given moment in the 1970s and 1980s, including Chavez and his family. Chavez’s life there was part of his decision to accept minimum wages and work for the cause. The UFW describes it as a vow of poverty. La Paz had a newspaper, a radio station, and a school. It was a place for people to build a community.

When Cesar Chavez died in 1993, his funeral was in Delano, then he was buried at La Paz. The UFW continues to operate at La Paz. The site is operated by the Cesar Chavez foundation and has since added an education and memorial center with a garden at Chavez’s burial site.

Nuestra Senora Reina de la Paz is now part of the Cesar Chavez National Monument, established in 2012 as part of the National Park Service.

Wikimedia Commons. Photo captured by Tony the Marine

5. Santa Rita Center (Phoenix, AZ)

The Santa Rita Center in downtown Phoenix, Arizona was built in 1962 by the Sacred Heart Parish. It was originally used as a classroom and community hall but quickly became the organizing center for Chicanos Por La Causa, a civil rights organization to support the area’s Latino community.

In 1972, Arizona passed a bill preventing farmworkers from collective bargaining, strikes, and boycotts. The Arizona branch of the UFW started to mobilize, marching to the state capital. Chavez, along with other national UFW leaders, traveled from California to join them.

In support of community organizers in Phoenix, Chavez fasted for 24 days at the Santa Rita Center. Thousands of farm workers and other supporters came to rallies and the daily masses. Famous supporters came including singer Joan Baez, presidential candidate George McGovern, and activist Coretta Scott King. King compared Chavez’s efforts to her late husband, Martin Luther King Jr’s.

During the fast, some local leaders were discouraged by the lack of progress with Arizona politicians. As they repeated “No, no se puede” (it can’t be done), Chavez’s UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta responded, “Si, si se puede!” (Yes, yes it can be done!) She repeated the call to those gathering outside and turned it into a rallying cry that continues to echo through Latino activist movements today.

The still-active community center is designated as a historic site on the Phoenix Historic Property Register.

Wikimedia Commons. © Paul Richards

6. 1966 March Route (Delano to Sacramento CA)

When farmworkers went on strike against grape growers around Delano, California, in 1965 they were at a significant disadvantage. Their right to collectively bargain was not legally protected. Vineyards brought in outside workers to break the strike. Chavez, Huerta, Itiliong, and other UFW leaders knew they needed to use a different strategy to raise awareness among the wider public: the march.

The march was inspired by the tactics of the African American Civil Rights Movement, including the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama the previous year, the Mexican Revolution, including leader Emiliano Zapata's Plan de Ayala, and the Christian act of Peregrinación, or pilgrimage. Marchers left from Delano, California the day after Congressional hearings on farm workers' rights, drawing national press attention. The 340-mile route was followed by more than 100 people in 1966. Thousands of workers and their families joined marchers along the way, some for only a day, others for longer. As protestors marched, they carried banners of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the American Flag, and the NFWA flag. People sang and chanted slogans, including “Viva Huelga!” and “Viva Chavez!” They marched through 42 cities and towns in just under a month to secure a new contract and raise awareness.

During the journey, Schenley, one of the larger growers, reached out to Chavez to negotiate. The march was hurting their public image even more than their bottom line. While this was the only contract as an immediate result of the march, the Delano to Sacramento March remains a symbol of Latino Farmworkers' ability to organize and impact change.

Tags

- latino history

- mexican american

- chicano civil rights movement

- chicano heritage

- latino heritage

- hispanic and latino american history

- hispanic heritage

- california

- arizona

- farm workers

- cesar chavez

- dolores huerta

- larry itliong

- union

- places of...

- places of article

- protest

- 20th century farming

- 20th century

Last updated: September 15, 2025