Last updated: May 21, 2024

Article

What We’re Learning and Why it Matters: Long-Term Monitoring in the National Capital Region

After more than fifteen years of monitoring, we've learned a lot about park ecosystems, how they're changing, and what they may look like in the future.

By Crystal Chen, NCRN I&M Science Communication Intern

The National Park Service preserves some of America’s most special and treasured places. Knowing which key natural resources are found in the parks, and whether they are stable or changing, can help park managers make sound, science-based decisions about the future.

The National Capital Region Network (NCRN) is one of 32 Inventory & Monitoring networks building that knowledge. In 11 regional national parks, our scientists and partners collect long-term data on key natural resources—like plant communities, birds, and water quality—that we call "vital signs," because their condition can indicate the overall health of park resources. We analyze the results, track the changes, and provide information to decision-makers.

NCRN parks are a mix of natural and cultural areas that provide a unique glimpse into forest ecosystem health. We maintain precious biodiversity within a broader urban setting. There's still plenty we don't know, but there's a lot we do know.

What have you learned? What kinds of changes are you seeing?

The first few years of any monitoring program are devoted to figuring out what's "normal" for a given ecosystem. We collect data to establish a baseline, then determine the range of measurements that might be expected under typical conditions. With more than fifteen years of data for some resources, we’ve learned numerous key things about the ecosystems we study.

Forest Vegetation

- NCRN forests are more diverse and harbor more old-growth structure, when compared with forests in the Eastern Deciduous biome.

- Our parks have small forest patches that provide crucial habitat for biota in an urban setting. But, trees along the forest edge are vulnerable to climbing vines. Once a vine reaches the crown of a tree, the tree’s growth slows. At the forest edge, trees are already vulnerable to a more stressful environment (e.g., more wind and sun). Managing vines in trees along forest edges can help reduce tree mortality.

- Non-native vines are more abundant and increasing faster. Managing invasive vines is a great way to support trees along the forest edge, and forest patches.

A Forest Plot at Rock Creek Park in 2012 and 2016 Showing Seedling and Understory Regrowth

Left image

2012, Before deer management

Right image

2016, On-going deer management

Forest Regeneration

Regeneration of trees is critical for the forest ecosystem. Trees provide habitat for plants and animals, filter water and air that we drink and breath, and provide the cool leafy shade enjoyed by visitors in the summer heat.- Forest regeneration is low for all parks.

- Our data are consistent with forest research conducted across the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast, showing that high populations of white-tailed deer harm forest regeneration capacity. In general, NCRN parks that practice deer management have seen a recovery in seedlings. Seedling numbers increased 19-fold at Catoctin Mountain Park and more than doubled at Rock Creek Park since deer management began. While a promising start, this effect requires continued effort over many years to sustain our forests.

- After a high-intensity fire at Prince William Forest Park, we have seen seedlings start to recover. Low-intensity fire doesn't show the same result.

- NCRN staff are working with colleagues in the Northeast Region to support park managers in taking actions to promote forest regeneration.

NPS/Thomas Paradis

Invasive Plants

More than non-native plants, native plants supply wildlife with the food and physical structure they need. Visitors and neighbors can support healthy wildlife and forests by growing native plants and removing non-native invasive plants from their yards. Invasive plants take advantage of forest stressors including: forest fragmentation, overabundant deer, forest pests, and light gaps caused by forest canopy disturbance.

- Invasive plants are pervasive and spreading.

- In forests, invasive shrubs are increasing faster than invasive herbs, trees, or vines. Ticks benefit from this increasing shrub cover, and given added risk to human health from tick-borne diseases, invasive shrubs are a high management priority.

- Do all invasive plants hinder the growth of tree seedlings? A study on invasive stiltgrass at Catoctin Mountain Park found more tree seedlings in patches of stiltgrass than in open areas. This plant may offer seedlings protection from deer browsing, since they can hide amongst plants deer don't like to eat.

- Invasive plants change habitat structure, which has a cascading impact on invertebrate communities.

NPS/Brolis

Forest Pests

- Beech leaf disease, was first found in Prince William Forest Park in 2021 and has since been found in C&O Canal in 2023. Potential forest impacts could be dramatic and dire since beech are the most common tree species in the region.

- As of 2023, emerald ash borer (EAB) has killed more than 80% of the white, green, and pumpkin ash trees that were present in NCR parks in 2014.

- Since arriving in 2021, spotted lanternfly has been observed throughout NCR parks. It is unlikely to cause as much mortality as emerald ash borer, because it feeds on a wide range of plants and is rarely lethal on its own.

- Hemlock wooly adelgid and elongate hemlock scale have killed many eastern hemlock trees. Parks (like Prince William Forest) preserve their hemlock patches with regular insecticide treatment. Hemlocks grow along streams, providing shade for brook trout that rely on cold water for survival. An NCRN census of hemlocks in 2015 found 112 standing hemlock trees, 34 of which were alive. 38% of living hemlock trees were infected with the adelgid or the scale.

- American chestnut trees were devastated by chestnut blight fungus in the early 1900s. In 2014, we surveyed surviving American chestnuts in all parks except Antietam and Manassas. We documented 234 trees. Most were small and showed no signs of flowers or fruit.

-

A summary of forest pests through 2023 describes current and upcoming threats to NCR parks.

Sea Level Rise

- Relative sea level in Washington DC has been increasing since 1924 at an annual rate of 3.43 mm per year, with higher rates recorded in recent decades. This could lead to more frequent and severe flooding in low-lying areas.

- Flooding can change the vegetation and wildlife able to survive in freshwater tidal marshes of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers. Transformation of high marsh into low marsh could benefit spawning fish, but also reduce the ability of the marsh to trap sediment.

-

Early findings from marsh elevation monitoring in national parks of the mid-Atlantic and northeast suggest that some wetlands are more resilient to climate change. Data from the freshwater tidal marshes of Dyke Marsh in George Washington Memorial Parkway (based on monitoring from 2006-2019) and Kenilworth Marsh and Kingman Lake in National Capital Parks-East (based on monitoring from 2002-2019) show signs of these marshes' resiliency and the challenges to come in the face of sea level rise.

NPS / C. Shafer

Amphibians

- Amphibian populations are fairly stable. Over 15 years of data collection, no species experienced severe decline or unexpected growth.

- Wetlands that are larger and closer together have more species. The biggest factor for species richness is the hydroperiod (ability of a wetland to retain water during the breeding season).

- Longer, hotter summers and urban development can impair habitat and water quality. Parks can protect amphibian habitat by: 1) increasing hydroperiods, 2) keeping wetlands connected, 3) limiting roads near wetlands.

D. Tallamy

Birds

- NCRN bird populations are fairly stable. Bird community trends were stable in 12 parks, increased in 4 parks, and decreased in 1 park.

- Since 2007, we’ve observed 157 species in 11 NCRN parks, 22 of which are high priority for conservation. We observed the highest number of forest bird species at Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

- A recent article examines how six interior forest breeding birds are doing in NCRN parks.

- NCRN parks provide critical breeding habitat for birds. Forest birds fare worse at forest edges and in more urban parks.

- Since the beginning of grassland bird monitoring, we’ve observed 7 grassland-dependent species that we had not seen in forests. Grassland habitats are declining in the eastern United States due to natural succession to forests, fire suppression, and fewer open agricultural fields.

- A recent analysis of two focal grassland birds—the eastern meadowlark and the grasshopper sparrow—at four battlefield national parks, showed that how grasslands are managed effects the survival and reproduction of birds in those places.

Stream Biota

- NCRN streams are usually home to aquatic species that are less sensitive to changes in water quality. Urban development and other land use impair water quality and stream structure.

- More sensitive species have been observed in streams with good water quality. At Prince William Forest Park, we observed sensitive macroinvertebrates including mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies.

- Freshwater sponges were observed at five parks.

- Herring and American eel populations are in decline. They face great difficulty migrating and reproducing because of dams and other barriers.

NPS

Stream Water

- Winter road salting is one of many factors that is increasing water conductivity in streams. Conductivity shows the level of dissolved material in streams. High levels cause harm to fish and aquatic invertebrates who can’t survive in increasingly salty water. In the larger DC area, our monitoring data shows the otherwise unseen downstream effects of pollution from many sources.

- Streams in Rock Creek Park and Antietam National Battlefield have high concentrations of phosphorus and nitrogen. This can cause algae to grow faster than ecosystems can handle.

- We recorded very low summer-time levels of dissolved oxygen at Young’s Branch (the main watershed in Manassas National Battlefield). In the summer, low water levels allow for higher water temperatures and lower oxygen levels that stress aquatic life. In some years, the stream completely dries up. Aquatic life that can’t withstand drying or can’t repopulate quickly once the stream is flowing again, will be severely harmed.

- Brook trout rely on coldwater streams at Catoctin Mountain Park. Based on our modeling, we expect to have no coldwater streams within the next 50 years in NCRN parks. This means that brook trout will no longer be a part of our aquatic ecosystems. Check out this map of coldwater refugia (and learn how to use it).

Air Quality

- Recent weather patterns show that temperatures are rising year after year.

- Ozone levels are declining.

- Sulfur and nitrogen deposition rates have improved dramatically over the past 20 years. Although air pollutant levels are decreasing, they are still regularly above EPA standards and are a stressor to vegetation and wildlife. High levels of acid deposition cause soil acidification, especially in northern parks.

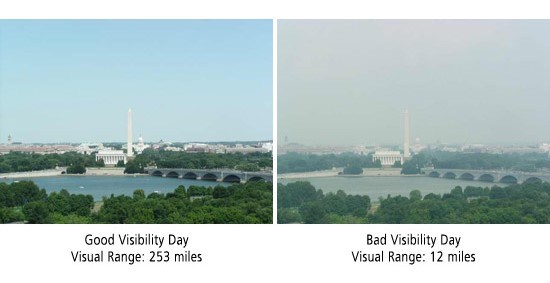

- Visibility is poor at National Mall and Memorial Parks. In 2021, the estimated visual range was between 41 and 114 miles. Without pollution, estimated visual range would be between 80 and 158 miles.

Supporting Information

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- george washington memorial parkway

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- ncrn

- monitoring

- water quality

- science

- vegetation

- vegetation and soils

- climate

- climate change

- climate change effects

- streams

- stream monitoring

- streams monitoring

- resilience

- contaminants

- marsh

- landbirds

- grassland

- grassland birds

- landbird community monitoring

- amphibian

- amphibian monitoring

- trends

- flood

- national capital region network

- inventory and monitoring

- research

- plants

- forest pests

- air quality

- emerald ash borer

- beech leaf disease

- hemlock woolly adelgid

- surface elevation table

- potomac

- wildlife

- deer management

- salamander

- wetland

- nature

- vernal pool

- bird

- living webpage

- forest

- invasive

- stream biota

- invasive plants