Last updated: December 2, 2021

Article

Stiltgrass and Tree Seedling Recovery

Thomas Paradis/NPS

Importance

Eastern forests have many stressors. Two of the biggest are overabundant deer populations and non-native invasive plants. But how do these stressors interact? If deer populations go down, do invasive plants explode and hamper forest recovery?

A recent analysis of data from Catoctin Mountain Park, where extensive monitoring has tracked forest changes before and during deer population management, looked at one of the most concerning invasive species: Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum).

Background

Japanese stiltgrass is a low-growing invasive grass that forms a dense carpet in shady forests. Overabundant populations of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in forests eat up small plants, tree seedlings, and other greenery within reach (except for stiltgrass and a few other species deer don’t like).

High deer populations eat tree seedlings and can cause a dense understory of browse-tolerant or deer-avoided plant species to form, sometimes referred to as a “recalcitrant” understory layer, because it may impede tree regeneration. Japanese stiltgrass may be part of these recalcitrant layers because deer avoid eating it. As a rapidly expanding invasive, park managers and scientists wanted to know if Japanese stiltgrass was threatening to shade out young tree seedlings during forest recovery.

Forest vegetation data for Catoctin Mountain Park, which has managed deer populations since the fall of 2009, were analyzed to answer three questions about deer, stiltgrass, and forest recovery:

Has lowering the deer population increased the number of native tree seedlings?

Schmit et al./NPS

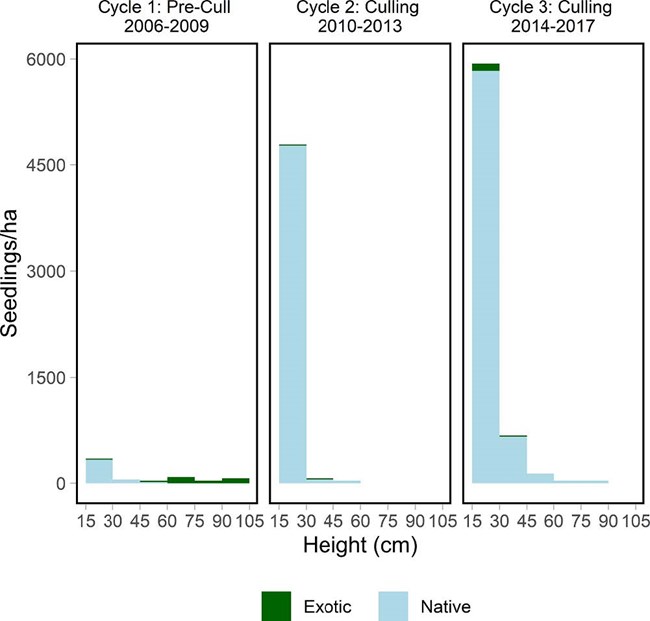

Yes. Lowering deer populations at Catoctin has allowed more native tree seedlings to sprout and survive. In each cycle of vegetation monitoring that has followed initiation of deer population control, more and more seedlings have been observed (Figure 1). These seedlings however, occupy the smallest measured size classes (the majority are under 30 cm or about 1 foot tall) and will require decades to grow to sapling and young tree stages.

Does stiltgrass form a “recalcitrant” understory layer that restricts seedling growth?

Schmit et al./NPS

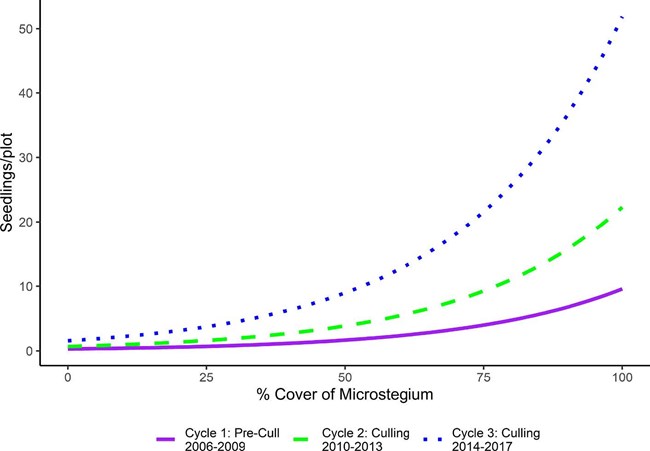

Stiltgrass does form a dense understory layer, but it does not appear to prevent seedling growth. While seedlings increased throughout the park, areas with the highest cover of stiltgrass tended to see the biggest increase in seedlings (Figure 2). In fact, it may be that the dense layer of stiltgrass in infested areas could help seedlings by disguising and therefore protecting them.

Does dense stiltgrass persist when deer populations are managed/lowered?

Schmit et al./NPS

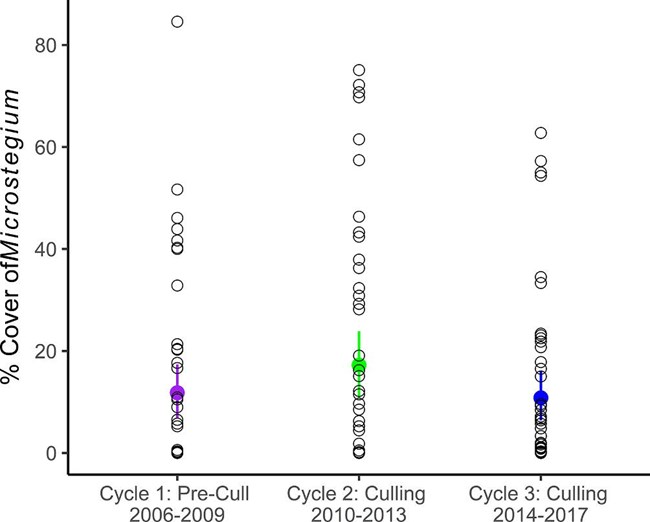

Maybe. After deer management began at Catoctin, stiltgrass levels initially rose, much as they have through other National Capital Area parks. As deer management continued, stiltgrass started to decline and decreased back to the levels seen prior to deer management (Figure 3). Stiltgrass often requires some kind of disturbance, such as that caused by deer, to persist in an area. Now that deer populations have been eliminated, future monitoring will reveal if stiltgrass will persist or continue to decline.

Discussion

Tree seedlings at Catoctin increased 11-fold with deer management over the course of 8 years, and Japanese stiltgrass did not appear to hold them back. That is good news for the first step of forest recovery and regeneration at Catoctin.

The incredible tree seedling increase observed at Catoctin was possible in part because seedling levels had gotten so low as to be almost non-existent. So far, the new seedlings are almost entirely under 30 cm, or about 1 foot tall. For further steps toward recovery, the seedlings need to make it into the sapling size class by measuring at least 1 cm dbh (diameter at breast height), which is usually at 1.5 – 2 meters (about 5 to 6 ½ feet) tall. Depending on many factors including available light, species type, and various stressors, it may take a decade or more for a young tree to grow from 30 cm to 1.5 meters tall.

Forest recovery is a long-term prospect and can be further prolonged by factors unrelated to deer or invasive plants. A majority of Catoctin’s new seedlings are ash species and will likely be vulnerable to emerald ash borer before reaching maturity. All the more reason to continue to protect young trees in the long process of forest recovery.

How does this apply to management?

-

Continue managing deer populations – it does result in more tree seedlings!

-

Don’t delay deer management because of stiltgrass. It doesn’t prevent seedling recovery.

-

Be patient about tree regeneration and forest recovery: think in decades. New seedlings are like kindergarteners who we want to see grow into adults. It’s going to take time.

Citation:

John Paul Schmit, E. Matthews, and A. Brolis. 2020. Effects of culling white-tailed deer on tree regeneration and Microstegium vimineum, an invasive grass. Forest Ecology and Management. Volume 463, May 1, 2020.

Learn More about the National Park Service's Inventory & Monitoring Efforts

To help protect natural resources ranging from bird populations to forest health to water quality, National Park Service scientists perform ecological Inventory & Monitoring (I&M) work in parks across the country. The National Capital Region Network, Inventory & Monitoring program (NCRN I&M) serves national parks in the greater Washington, DC area. To learn more about NCRN I&M forest monitoring, you can visit the NCRN forest monitoring webpage.

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- baltimore-washington parkway

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- fort dupont park

- george washington memorial parkway

- great falls park

- greenbelt park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- kenilworth park & aquatic gardens

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- piscataway park

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- forest

- ncrn

- i&m

- forest regeneration

- deer management

- white-tailed deer

- tree seedlings

- forest recovery

- invasive plants

- japanese stiltgrass

- non-native species

- recalcitrant layer

- understory

- forest monitoring

- natural resource quarterly

- summer 2020

- resource brief

- resilient forest management