Last updated: March 8, 2024

Article

NCR's Forest Interior Birds

Credit: Kelly Colgan Azar / Flickr

A Focus on Six Forest Birds

Many bird species make their homes in the leafy forests of the National Capital Region’s (NCR) national parks. But some are specially adapted to only the shadiest and quietest core of the forest. Here we take a closer look at six of these birds that nest and breed only in the so-called “forest interior,” to learn how they’re faring. The six birds in question are: wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla), Kentucky warbler (Geothlypis formosa), Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla), hooded warbler (Setophaga citrina), and scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea).

Interior forest breeding birds are a high conservation priority according to the international bird conservation group Partners in Flight. They are sensitive to the forest fragmentation and the conditions at forest edges that are often found in more developed areas like the Mid-Atlantic and they avoid smaller, disjointed, or narrow woodlands.

Our six species also happen to be neotropical migrants that come north in the spring to breed in North America’s eastern deciduous forest then head south in the fall bound for the neotropical havens of Central and South America. Conservation of neotropical migratory birds requires a substantial amount of coordination among nations, agencies, and non-governmental organizations, as they need suitable habitat during every stage of their annual migration cycle. NCR national parks are critical in providing migratory stopover for many and breeding habitat for our six forest interior birds.

How are forest birds faring in the National Capital Region?

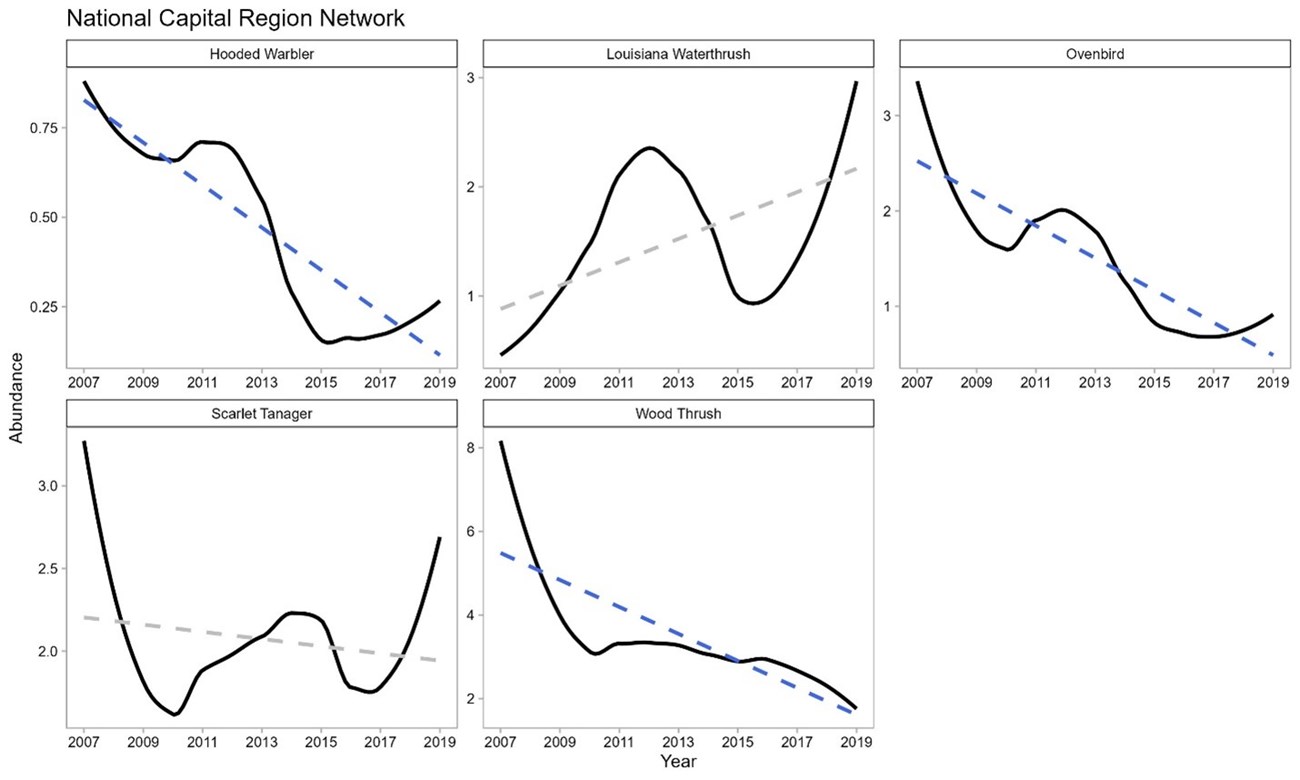

Park service ecologists with NCR’s Inventory and Monitoring program (I&M) have been monitoring forest birds since 2007, and now in 2023, we can start to see how populations are changing over time. Each year field crews monitor birds at about 385 forested plots, twice every summer using point count methods at two distances: near (under 50 meters) and far (50-100 meters). A recent report by Ladin et al. (2021) using this data presents detailed information about the shifts in occupancy and abundance for over 100 forest bird species.

Of our six interior forest breeding birds in NCR parks, wood thrush, ovenbird, and scarlet tanager are the most common (abundant). Each species has a slightly different occupancy level at each park, in part because there are some key differences in their habitat needs. For example, both hooded warblers and scarlet tanagers prefer mature deciduous forests, but hooded warblers make their nests in dense understory while scarlet tanagers nest high up in the canopy. Louisiana waterthrushes breed along forest streams and tend to make their homes in parks with clean, fresh water. Overbirds dislike a thick understory; wood thrush prefer a moderate one with moist soil and decaying leaf litter. The forests of NCR parks accommodate the varying habitat needs of these forest interior breeding species, making all six excellent indicators of a healthy forest ecosystem.

| Species | NCRN | ANTI | CATO | CHOH | GWMP | HAFE | MANA | MONO | NACE | PRWI | ROCR |

| Hooded Warbler (Setophaga citrina) | -0.02 * | n/a | 0.06 | n/a | n/a | -0.36 | n/a | n/a | n/a | -0.05 | -0.07 |

| Kentucky Warbler (Geothlypis formosa) | -0.16 * | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | -0.07 | n/a | n/a | -0.16 | n/a |

| Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) | 0.02 | n/a | 0.05 | 0.02 | -0.09* | 0.1 | -0.12 | -0.44 | n/a | 0.03 | 0.1 |

| Ovenbird (Seiurus aurocapilla) | -0.01* | n/a | 0.03* | -0.02 | -0.03 | -0.09 | -0.07 | -0.05 | 0.08 | -0.02* | -0.14* |

| Scarlet Tanager (Piranga olivacea) | -0.03* | -0.04 | -0.04 | -0.01 | -0.06* | -0.08* | -0.01 | 0.20* | -0.05 | -0.02* | -0.07 |

| Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) | -0.04* | -0.04* | -0.04* | -0.05* | -0.09* | -0.06* | -0.11* | -0.05 | -0.07 | -0.02* | -0.07* |

NPS / Nicholas Tait

Beyond the NCR

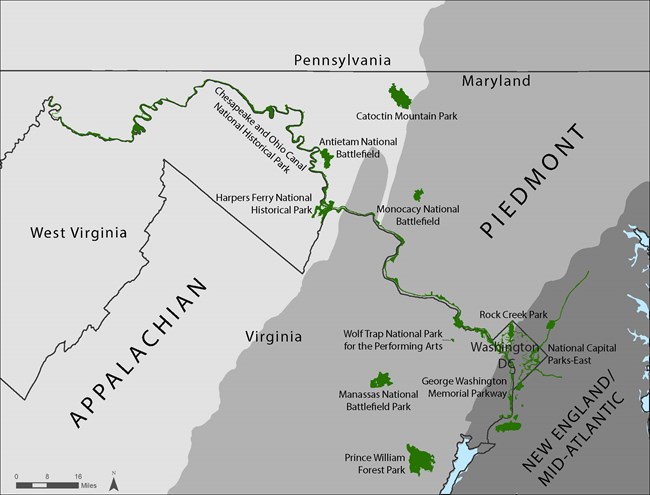

How are our six forest interior breeding species faring in regions beyond NCR national parks? To answer this question, we looked at data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), a long-term bird monitoring program that tracks the status and trends of North American bird populations. This survey splits North America into 66 ecologically distinct Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs). NCR parks fall within three of these regions: the Appalachian, Piedmont, and New England/Mid-Atlantic.

Comparing data for the same time period (2007-2019), data from the BBS shows that our six interior breeding birds are doing better in their Bird Conservation Regions than in NCR’s small, high-quality parks. This is in part because of the variation in quality of the habitat between the natural areas of the parks versus the mix of urban, natural, and agricultural areas of the larger BCRs.

Parks Can Help Mitigate Threats to Forest Birds

Many stressors combine to drive declines in forest bird populations, especially our six forest interior breeding species. Human development of natural areas leads to forest fragmentation and habitat loss, which reduces expansive forested areas that the birds require in order to thrive. Other threats to forests contribute to the woes of these species, as well. Nonnative pests like emerald ash borer or diseases like beech leaf disease can plague an ecosystem, reducing tree cover and potential breeding sites for birds. High densities of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) reduce vegetation cover, especially in the shrub layer where some forest interior birds construct their nests. Forest bird numbers have also taken a hit due to consistent mortalities during migration and high predation and parasitism rates during breeding. Free-ranging cats are another serious issue. In the United States alone, over 60 million cats are responsible for over 1 billion bird (and over 6 billion mammal) deaths each year (Cornell Lab of Ornithology). Millions more birds are killed annually through collisions with buildings, vehicle strikes, and environmental contaminants as well.

NCR parks provide critical habitat for forest interior breeding species, without which the negative population trends would likely be even worse. Still, there are important management actions parks can take to promote bird populations:

- Protecting and restoring large-scale forest habitat by preventing fragmentation

- Deer management that relieves pressure on forest vegetation and regeneration at some parks may be having beneficial effects on local forest breeding birds.

- Controlling nonnative, invasive plants and pests can also help ensure healthy forest habitat.

- Encouraging park neighbors to keep cats indoors.

Further Reading

Learn more about forest birds in National Capital Region national parks in, Ladin ZS and Others. 2021. Forest bird monitoring in the National Capital Region Network: Summary report 2007–2017. Natural Resource Report. NPS/NCRN/NRR—2021/2292. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2287175

Learn More about the National Park Service's Inventory & Monitoring Efforts

To help protect natural resources ranging from bird populations to forest health to water quality, National Park Service scientists perform ecological Inventory & Monitoring (I&M) work in parks across the country. The National Capital Region Network, Inventory & Monitoring program (NCRN I&M) serves national parks in the greater Washington, DC area. To learn more about NCRN I&M bird monitoring, you can visit the NCRN bird monitoring webpage.

References

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2023, August 9). FAQ: Outdoor Cats and their effects on birds. All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/faq-outdoor-cats-and-their-effects-on-birds/

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- catoctin mountain park

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- george washington memorial parkway

- greenbelt park

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- monocacy national battlefield

- national capital parks-east

- piscataway park

- prince william forest park

- rock creek park

- ncrn

- ncrn im

- scarlet tanager

- hooded warbler

- wood thrush

- kentucky warbler

- louisiana waterbird

- forest interior breeding birds

- forest birds

- natural resource management

- forest management

- birds

- forests

- nature

- ovenbird

- forest bird brief