Last updated: June 26, 2023

Article

Fire and the Future of the Forests at Prince William Forest Park

By Nicholas Tait, NCRN I&M Science Communication Intern

NPS / Mike Custodio

The forest at Prince William Forest Park (PRWI) is changing. Fire, and the suppression of fire over most of the past century, has altered the composition and structure of the park’s piedmont forest. PRWI’s forest today, which has also seen impacts from white-tailed deer, pests, diseases, and invasive species, looks different than it did a hundred years ago.

The NPS National Capital Region Inventory & Monitoring Network (NCRN I&M) began monitoring forest vegetation at Prince William to quantify these changes and identify their implications on forest structure and health. I&M scientists recently analyzed monitoring data from 2006 to 2017 to look at the effects of fire on the forest.

NPS

Fallout from a Wildfire

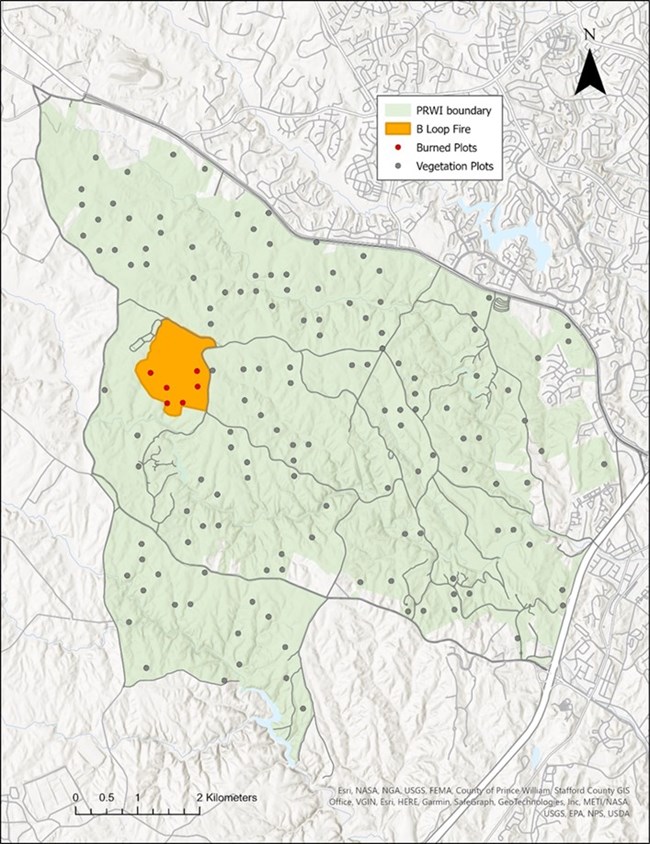

On March 27, 2006, right as I&M kicked off their very first season of forest vegetation monitoring, a wildland fire ignited near the B-loop of Oak Ridge campground in Prince William. The fire, human-caused and dubbed the “B-Loop Fire,” blazed through 318 acres in nine days before firefighters extinguished it (Figure 1). Fire can often be a strong influence on forests, and this one was noted for being unusually hot and destructive—in some spots killing up to 75% of forest canopy trees. In the years since, I&M scientists have gathered and compared data from the 6 forest monitoring plots in the burned area with the other 139 unburned plots throughout the rest of the park. They found that burned plots experienced a burst of vegetative growth and are now markedly different from those unaffected by the fire.

Burned plots had:

- 3.5 times more tree seedlings and 5 times more shrub seedlings than unburned plots

- A smaller percentage of deer browse on seedlings. This is possibly due to thicker vegetation making these seedlings less accessible, or maybe there were simply too many seedlings for the deer to consume.

- A sapling layer now mostly made up of fire-tolerant oaks and hickories, unlike unburned plots where fire-sensitive species like American beech and red maple typically dominate.

This 2006 fire demonstrated that burns (prescribed or otherwise) can have a lasting impact on forest structure and composition.

Oaks and Hickories Love Fire

Historically, the piedmont forests of the eastern United States have followed a predictable pattern in which certain species dominate at different stages of forest succession. Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) and tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) are some of the first trees to emerge as a cleared area reverts to forest. When these sun-loving, “pioneer” species reach maturity and form a canopy, shade-tolerant species like oaks (Quercus spp.), hickories (Carya spp.), red maple (Acer rubrum), and black gum (Nyssa sylvatica) start to thrive and dominate the understory. With fires continuously rolling across eastern forests over the centuries, thicker-barked oaks and hickories proved to be more flame-resistant than maples and black gums. With enough burns, oaks and hickories come to dominate the canopy, creating a naturally regenerating forest that can last for generations and support a wide variety of wildlife. This is the succession scenario to which most organisms of the eastern deciduous forest have adapted.

In the early twentieth century, however, Americans took up the practice of fire suppression, greatly reducing fire throughout the eastern United States. Piedmont forests like Prince William Forest Park saw fewer wildfires over the years and saw their forest tree succession altered. Fire suppression favored shade-tolerant species more sensitive to fire. It set off a process, known as mesophication, characterized by fewer fire-tolerant species like oaks and hickories and an increase of “mesic” species more adapted to cool, wet, shady, and fire-free conditions, like red maple and American beech (Fagus grandifolia).

Due to long-term lack of fire in Prince William, we are seeing a decline in oak-hickory species across the unburned sections of the park and a continued dominance of mesic species. Without fire disturbances, these mesic trees will become more important and eventually come to dominate the canopy, which could result in less overall biodiversity across the park. Mesophication, combined with continued over-browsing of seedlings by heavy populations of white-tailed deer, poses a real challenge to the biodiversity of PRWI. Oak-dominated forests are uniquely important in supporting a wide variety of other flora and fauna. Examples of this importance has been proven through various findings from other studies:

- Brose et al. (2014) found that acorns are a crucial food source for many vertebrates.

- Birds are more abundant in oak dominated forests than maple dominated forests, likely due to the greater food availability (Rodewald and Abrams, 2002).

- Narango et al. (2020), found that Quercus is the most important keystone genera in supporting Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) diversity in North America. The next most important trees are willows (Salix spp.) and cherries (Prunus spp.), which are not common in Prince William, along with pines (Pinus spp.), which are declining.

- Canopy composition affects the diversity of herbaceous species on the forest floor, with pure oak stands having significantly higher vegetation diversity than those with maples (Fralish 2004, Rogers et al. 2008).

NPS / Brolis

Prescribed Fire for Forest Management

Prescribed (Rx) burns under controlled conditions can be a key management tool in restoring a forest by reversing the effects of mesophication. It also can reduce woody vegetation density and has the added benefit of minimizing the potential impact of future wildfires by burning up hazard fuel (dead trees and leaf litter).

Resource managers at Prince William have been conducting prescribed fires at the park with these objectives in mind. The Oak Ridge prescribed fire in March 2023 successfully burned through 46 acres of forest between the Oak Ridge Trail and Scenic Drive. The park plans to burn the remaining 59 acres in fall 2023 or early spring 2024. The objectives of the fire were to restore fire to the ecology of the forest and reduce hazard fuel, nonnative species, and the density of woody shrubs.

An NPS fire effects monitoring team will track the effects of the Oak Ridge prescribed fire over the next 10 years to gauge effectiveness of the fire in meeting park goals. Hopefully the area will show greater oak and hickory regeneration, along with less deer browse and fewer nonnatives—similar to what we saw with the B-Loop Fire. Further use of both prescribed fire to shape the mix of successful tree species, coupled with the implementation of deer population reductions to curb the browse pressure on these new seedlings, will be crucial in promoting forest resilience at Prince William Forest Park and helping it to resist future stressors.

This article is based on findings in: Schmit, J.P., E. Matthews, and A. Brolis. 2023. Trends in Woody Forest Vegetation in Prince William Forest Park, 2006-2017. Natural Resource Report NPS/NCRN/NRR—2023/2495. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Learn More about the National Park Service's Inventory & Monitoring Efforts

To help protect natural resources ranging from bird populations to forest health to water quality, National Park Service scientists perform ecological Inventory & Monitoring (I&M) work in parks across the country. The National Capital Region Network, Inventory & Monitoring program (NCRN I&M) serves national parks in the greater Washington, DC area. To learn more about NCRN I&M forest monitoring, you can visit the NCRN forest monitoring webpage.

References

Brose, PH, DC Dey, and TA Waldrop. 2014. The fire–oak literature of eastern North America: synthesis and guidelines. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-135. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research Station. 98 p.

Fralish, JS, 2004. The keystone role of oak and hickory in the central hardwood forest. In: Spetich, M.A. (Ed.), Upland oak ecology symposium: history, current conditions, and sustainability. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS–73. Asheville, NC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, 2004, 311 p.

Narango, DL, DW Tallamy and KJ Shropshire. 2020. Few keystone plant genera support the majority of Lepidoptera species. Nature Communications 11:5751.

Rodewald, AD and MD Abrams. 2002. Floristics and avian community structure: Implications for regional changes in eastern forest composition. Forest Science 48: 267–272.

Rogers, DA, TP Rooney, D Olson, and DM Waller. 2008. Shifts in southern Wisconsin forest canopy and understory richness, composition, and heterogeneity. Ecology 89 (9), 2482–2492.