Part of a series of articles titled Disability and the World War II Home Front.

Article

Disability and the World War II Home Front: Introduction

This series examines some of the many ways that disability intersected with and informed people’s experiences on the World War II home front.

Courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum. No known restrictions.

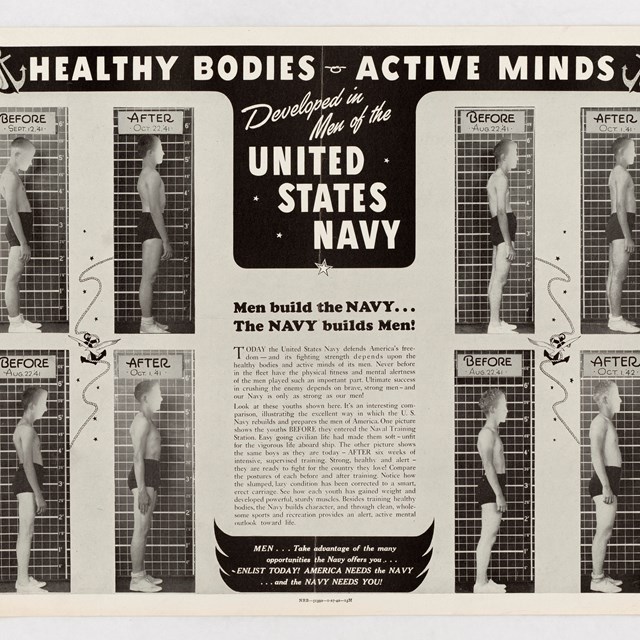

World War II was a time of enormous upheaval and rapid change. Before World War II, the United States had a relatively small military. Mass mobilization and conscription involved the physical and psychiatric examination of 18 million drafted and enlisted men and 350,000 enlisted women. The military used these exams to separate those they deemed suitable for combat from those who were “unfit” for service. With a rejection rate of over 40%, assessing moral, mental, and physical fitness on this scale drew widespread attention to disability across the country.

For those who wanted to serve, being screened out of the military could be frustrating. Many people with disabilities continued to look for other ways to participate and contribute to the war effort, including as workers in the defense industries. Mechanization during the preceding decades had led to increased discrimination against disabled workers. By maximizing output and profit, the efficiency of machines incentivized companies to redefine the qualities of a “good worker.” Industrial employers increasingly opted for non-disabled workers whose bodies could be easily replaced like parts in a machine.

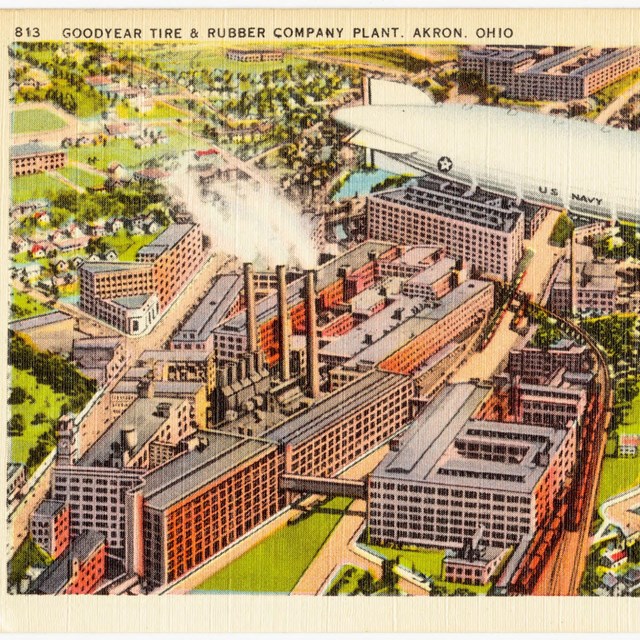

During World War II, however, wartime labor shortages and concerns about manpower lowered barriers to defense jobs for people with disabilities, women, people of color, and those who lived at the intersection of those identities. With support from vocational rehabilitation training programs, both industrial and support jobs opened to people with congenital and acquired disabilities that preceded the war, as well as people who had recently acquired them while serving in the military or working at defense plants.

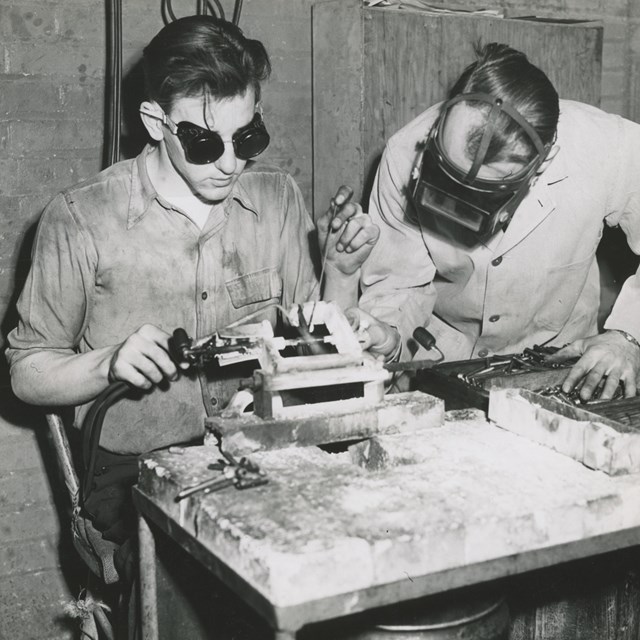

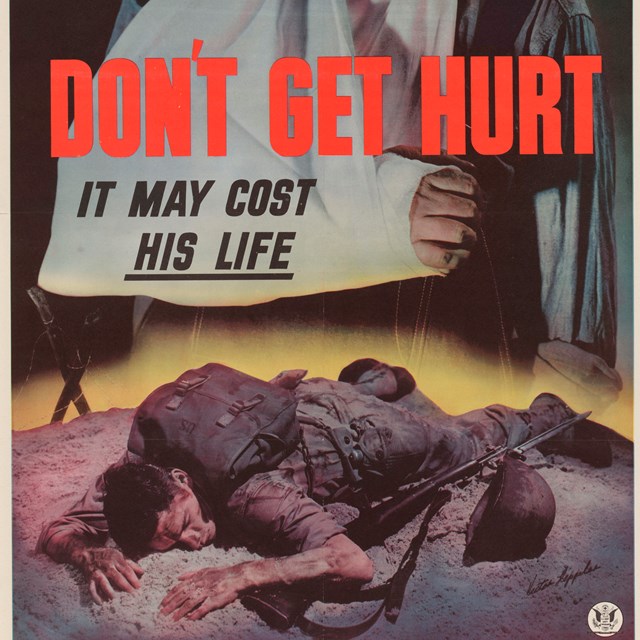

Indeed, the dangers were not limited to the fighting overseas and espionage and coastal attacks at home. Defense workers encountered many hazards on the home front as they tried to maximize efficiency and keep up with the demanding pace of production. Working in defense plants involved a high level of risk that could result in temporary or permanent disabilities, and even death.

Courtesy of Hennepin County Library, Kittleson World War II Collection. Public domain.

Returning soldiers also faced challenges as they readjusted to civilian life. World War II saw the renovation, recommission, creation of dozens of hotels, recreation camps, and veterans’ hospitals and care homes for those who became wounded or diseased. Unlike civilians who became injured during wartime, however, newly disabled veterans found it much easier to acquire jobs after the war. In addition to receiving military pensions, the GI Bill streamlined access to education and home ownership for veterans and their families.

Civilians with disabilities, on the other hand, could not qualify for veterans’ benefits and had much more difficulty accessing these essential paths to economic stability. Although some received workers’ compensation, many companies did not want to pay for these benefits in the long term. Workers’ compensation law also required employers to compensate workers with partial disability at a higher rate if they experienced a second, totally disabling accident.

As expanded access to jobs began to disappear after the war, civilians with disabilities found themselves among the “last hired, first fired.” Some companies prioritized putting veterans back to work, while other employers rejected people with disabilities to avoid financial responsibility for their care.

Although World War II had greatly expanded awareness of disability in the United States, society continued to exclude most disabled Americans from participation in public life. During World War II, people with disabilities had demonstrated their willingness to work and their aptitude for a wide range of jobs. However, employers’ unwillingness to provide accommodations or change inaccessible work environments continued to lock them out of jobs. Job discrimination left disabled people without the means to support themselves and forced them to rely on financial assistance from family members or the government. This cycle reinforced concerns about “dependency” that fueled disability discrimination.

Frustration with demeaning attitudes and discriminatory policies continued to grow, galvanizing organizations like the American Federation of the Physically Handicapped and Blind Veterans Association to speak out. However, disability rights activism for equal access to public transportation, education, and jobs would not result in federal civil rights protections until several decades later.

-

Unfit for Service

Unfit for ServiceExplore some of the reasons behind the draft's rejection rate of over 40% and the factors that disqualified people from military service.

-

Disabled Defense Workers

Disabled Defense WorkersDiscover how vocational rehabilitation programs opened doors to wartime defense jobs for people with disabilities.

-

Places of Disabled Defense Workers

Places of Disabled Defense WorkersThis article highlights a few of the many job opportunities that opened to people with disabilities during World War II.

-

Hazards on the Home Front

Hazards on the Home FrontDefense industry jobs could be more dangerous than serving on the front lines. How did wartime demand encourage unsafe conditions?

-

Christian Conscientious ObjectorsConscientious Objectors & Mental Health

Christian Conscientious ObjectorsConscientious Objectors & Mental HealthConscientious objectors stationed at a CPS camp in a mental hospital in Pennsylvania worked to create change in patients' treatment.

-

Christian Conscientious ObjectorsMental Hospital CPS Camps

Christian Conscientious ObjectorsMental Hospital CPS CampsMany of the Civilian Public Service camps where COs worked were in mental hospitals. Some of them are included on the National Register.

Bérubé, Allan. Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II. Twentieth anniversary edition with foreword by John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Federal Security Agency, US Office of Education, Vocational Rehabilitation Division. Vocational Rehabilitation: The Employment Efficiency of Physically Impaired Workers. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1943.

Jennings, Audra. “Disability and Industry.” The Human Machinery of War: Disability on the Front Lines and the Factory Floor, 1941-1945. Digital exhibit, The Ohio State University.

Kannapell, Barbara M. “The Forgotten Americans: Deaf War Plant Workers during World War II.” NADmag. February/March 2002.

Moran, Rachel Louise. “Men into Soldiers: World War II and the Conscripted Body.” In Governing Bodies: American Politics and the Shaping of the Modern Physique, 64–83. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Nielsen, Kim E. “We Don’t Want Tin Cups: Laying the Groundwork, 1927-1968.” A Disability History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2012.

Petersen, Peter B. “Occupational Safety in Times of Haste: Lessons Learned from American Workers on the Home Front During World War II.” Journal of Managerial Issues 6, no. 4 (1994): 408–27.

Rose, Sarah F. No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s-1930s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Smith, Tiffany Leigh. “4-F: The Forgotten Unfit of the American Military during World War II.” Master’s Thesis, Texas Woman’s University, 2013.

This series was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Consulting Historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

Last updated: December 16, 2024