Last updated: December 16, 2024

Article

Disability History and the WWII Home Front: Conscientious Objectors and Mental Health Reform

Three thousand CPS workers served at a total of 62 state mental hospitals around the country. One of these hospitals was the Philadelphia State Hospital, Byberry. [1] From 1942-46, the American Friends Service Committe (AFSC) operated CPS Camp 49 in Byberry. The COs served as attendants and orderlies, but their experiences and religious convictions also prompted them to aid their patients in additional ways through activism. [2]

Photo from the Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

Questions to Consider

When have your beliefs been challenged? How have you reacted to challenging situations?

Photo from Wayne D. Sawyer Papers in Civilian Public Service: Personal Papers & Collected Material (DG 056), Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

Conditions at Byberry

Over the duration of its time as a CPS camp, 187 COs worked at Byberry. Staffing was a problem at the hospital before the war, but the draft meant that the few full-time staff members joined the military, leaving a skeletal work force. [3] The US’s entry into World War Two also limited the ability to maintain adequate supplies and repair hospital infrastructure. Warren Sawyer, a CO, wrote home describing days where the ceilings and floors of the wards fell apart, doors were nailed shut, and lights went out because of circuit board failures. [4]In 1944, the unit was made up of 95 workers. For each shift that the COs worked at this time, there were one to four attendants to care for 350 patients. The COs’ inadequate training made the bleakness of the situation further apparent. The hospital provided classes on mental illness and therapeutic treatment, but it would often take over a month before the COs received proper orientation. What was taught to them was, according to CO Hal Barton, “idealistic,” and “the contrast between the ideal and the practical day-to-day ward situation was so striking as to be upsetting to say the least.” [5].

Ward B was known as the “violent ward.” In it, the patients frequently attacked each other. To try to limit this, full-time attendants strapped patients down to their beds for hours. [6] The COs found that the medical staff before them used very different care methods than they were trained in by the hospital. Former attendants would use violence to maintain control in places like Ward B, beating “difficult” patients with clubs, sawed off brooms, or a hose filled with buckshot. [7] The COs, whose belief in pacifism was part of their religious identity, were disturbed and wanted to ensure change.

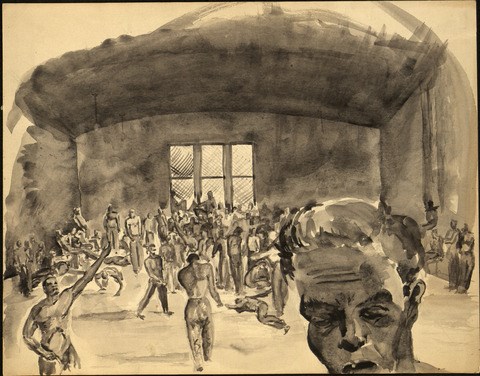

Painting from Peace Collection Ephemera (scpcGraphic0054; Accession number 82A-179), Swarthmore Peace Collection: Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

Nonviolence in Byberry and the National Mental Health Foundation

The first step that many COs at Byberry took in helping improve conditions was personal. They made a concerted effort to practice nonviolence control tactics with the patients. They avoided the use of physical restraints when possible. When intervention was necessary, the COs felt that the patients were grateful that they did not endure the violence and abuse that they suffered earlier. [8]In addition to their daily treatment of patients, the Byberry COs organized. This allowed them to care for each other, particularly in pursuit of fighting against racism. In 1941, President Roosevelt passed an executive order stating that “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries and in Government, because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” This allowed for African Americans to work in industries they had previously not been allowed to. However, they still faced discrimination. While not all CPS camps were segregated, many camps refused to allow African American COs. Some of the conscientious objectors at Byberry worked together to join the CPS Union (CPSU) established in 1944. Warren Sawyer, a CO who served at Byberry from the CPS camp’s opening in 1942 to its closing in 1946, wrote that the first Black CO arrived in 1945. The union members were aware of the challenges that he would face: the superintendent of the hospital had expressed to them that the non-CO employees did not want African Americans to serve as regular attendants. [9] White COs took efforts to reduce the challenges related to racism: prior to the first Black CO’s arrival, the Union circulated a paper among Byberry’s regular hospital staff that shared facts and policies related to the employment of African Americans [10].

In addition to organizing for their own well-being, the COs cared for their patients through their activism. Between 1944 and 1945, Harold Barton, Phil Steer, Willard Hetzel, and Leonard Edelstein founded the National Foundation for Mental Health (NFMH). The goal of the foundation was to improve the conditions in mental hospitals on a national level. For years, they worked with other Byberry COs to collect statements and document conditions. [11]

The NFMH received mixed responses from the stakeholders at Byberry. The Pennsylvania government was not supportive of the COs efforts. The Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Welfare and the Governor of Pennsylvania both argued that the work of the NMFH was inaccurate and presented a one-sided picture of the hospital. Other officials, however, acknowledged the need for reform in America’s mental healthcare system.

Byberry’s superintendent encouraged the reform efforts. He suggested that an expose should focus not just on CPS Camp 49, but conditions at hospitals across the country. The American Friends Service Committee, which ran the camp at Byberry, also supported the COs. They provided financial funding to the NFMH, which allowed them to pay attendants for testimonies and publish a newsletter across CPS units. [12]

Raising Public Awareness

Charlie Lord, another Quaker CO, was involved in a reform effort that captured visual proof of the abuses occurring at Byberry. Using a small camera he hid in his jacket, Lord shot three rolls of film worth of photographs. Other reformers, like Dorothea Dix and Nelly Bly, had used their writing to show neglect and abuse in hospitals. [13] But Lord and NFMH were some of the first to use photography.In 1944, when the first issue of NFMH’s inter-unit publication was released, Eleanor Roosevelt had expressed favorable views of the work. NFMH was able to arrange a meeting with Eleanor Roosevelt in 1945. They brought along Lord’s photographs, which disturbed Roosevelt. She was aware of worsening conditions in hospitals in states like Mississippi and Alabama, but was shocked to discover the site was actually in Philadelpha. Roosevelt’s support of the COs’ work helped to make the public aware of the state of psychiatric care. [14]

Months later, Lord’s photos were made public. Life published them in 1946, in an article titled “BEDLAM, 1946: Most Mental Hospitals Are a Shame and Disgrace.” The collection of CO summaries, along with several of Lord’s stills, were compiled as Out of Sight, Out of Mind in 1947. [15] The American public was shocked by these exposes. In “BEDLAM, 1946,” Lord’s photographs were featured with the captions “Idleness,” “Nakedness,” and “Crowding.” The images of mentally handicapped patients and the bleak conditions they lived in reminded some of the images they had seen of concentration camps.

The work of Lord, the NFMH, and journalists not only motivated a widespread audience for reform, but it also changed perceptions of CO work. While there was often judgement and discrimination against COs for refusing to fight, the daring work of those at Byberry reminded the public that they, too, were serving their country. [16]

This article was written by Emma Gruesbeck, an intern at the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, through a cooperative agreement with the National Council of Preservation Education (NCPE).

Notes and Bibliography

[1] Joseph Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors,” NPR, December 30, 2009, https://www.npr.org/2009/12/30/122017757/wwii-pacifists-exposed-mental-ward-horrors.

[2] “CPS Unit Number 049-01,” Mennonite Central Committee, 2015, https://civilianpublicservice.org/camps/49/1.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., Alex Sareyan, The Turning Point: How Men of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill (Scottsdale: Herald Press, 1994), 38-58.

[5] “CPS Unit Number 049-01,” Steven J. Taylor, Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2009), 202.

[6] “CPS Unit Number 049-01,” Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors.”

[9] “CPS Unit Number 049-01,” Sareyan, 38-58, Taylor, 126-134.

[10] Taylor, 100-101.

[11] “CPS Unit Number 049-01.”

[12] Ibid.

[13] Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors,” Charles R. Lord, “In the Ministry,” in Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors (Produccicones de La Hamaca, 2009), 149-160, “Dorothea Dix,” National Park Service, April 9, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/people/dorothea-dix.htm, “Nelly Bly,” National Park Service, March 22, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/people/nellie-bly.htm.

[14] “CPS Unit Number 049-01,” Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors,” “Eleanor Roosevelt,” National Park Service, June 11, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/people/eleanor-roosevelt.htm.

[15] “CPS Unit Number 049-01,” Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors,” Albert Q. Maisel, “BEDLAM, 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals are a Shame and a Disgrace,” Life, May 6, 1946, 102-118, Frank L. Wright, Jr., Out of Sight, Out of Mind (National Mental Health Foundation, Inc., 1947).

[16] Maisel, “BEDLAM, 1946,” Shapiro, “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors,” “CPS Unit Number 049-01.”

“CPS Unit Number 049-01.” Mennonite Central Committee. Last modified 2015. https://civilianpublicservice.org/camps/49/1.

“Dorothea Dix.” National Park Service. Last modified April 9, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/people/dorothea-dix.htm.

“Eleanor Roosevelt.” National Park Service. Last modified June 11, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/people/eleanor-roosevelt.htm.

“Franklin Delano Roosevelt.” National Park Service. Last Modified June 13, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/people/franklin-d-roosevelt.htm.

“Friends Asylum.” National Park Service. Last modified July 28, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/places/friends-asylum.htm.

“Kirkbride’s Hospital.” National Park Service. Last modified March 27, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/places/kirkbrides-hospital.htm.

Lord, Charles R. “In the Ministry.” In Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors, ed. Mary R. Hopkins, 149-160. Producciones de La Hamaca, 2009.

Maisel, Albert Q. “BEDLAM, 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals are a Shame and a Disgrace.” Life, May 6, 1946, 102-118.

Meldon, Perry. “Disability History: Early and Shifting Attitudes of Treatment.” National Park Service. Last modified October 31, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/disabilityhistoryearlytreatment.htm.

“Nelly Bly.” National Park Service. Last modified March 22, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/people/nellie-bly.htm.

Sareyan, Alex. The Turning Point: How Men of Conscience Brought About Major Change in the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Scottsdale: Herald Press, 1994.

Shapiro, Joseph. “WWII Pacifists Exposed Mental Ward Horrors.” NPR. December 30, 2009. https://www.npr.org/2009/12/30/122017757/wwii-pacifists-exposed-mental-ward-horrors.

Taylor, Steven J. Acts of Conscience: World War II, Mental Institutions, and Religious Objectors. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2009.

Wright, Frank L., Jr. Out of Sight, Out of Mind. National Mental Health Foundation, Inc: 1947.