Part of a series of articles titled Disability and the World War II Home Front.

Article

Hazards on the Home Front: Workplace Accidents and Injuries during World War II

According to historian Andrew E. Kersten, World War II defense industry jobs could be more dangerous than serving on the front lines.[1] Between 1942 and 1945, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported over 2 million disabling industrial injuries (including deaths) each year.[2] The Bureau of Labor Statistics classified disabling injuries as “partial” or “total,” and “temporary” or “permanent” to describe how much of a person’s body was affected and for how long. These categories were primarily used to track how many people were expected to return to work. However, they also hinted at deeper attitudes about disability that negatively associated dependency with deficiency.

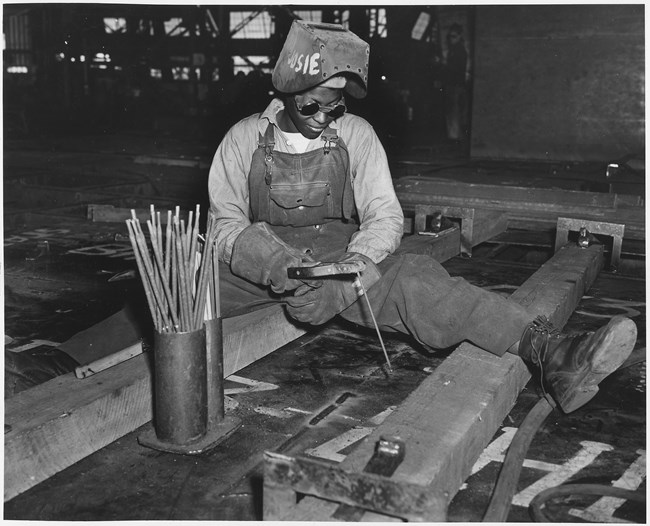

Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, News Bureau, ca. 1941-1945. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 514271), public domain.

Making Haste

The dangers of home front production stemmed from several factors: incentivized efficiency, unsafe conditions, and inexperienced (and often untrained) personnel. After the onset of World War II, the defense industries grew at a rapid pace. The federal government supported the construction of new factories. Other existing facilities were converted for wartime uses. Plants that had previously manufactured cars, refrigerators, and other domestic products began to produce ammunition, guns, and tanks.

Factories also saw an influx of workers who lacked experience and training. As seasoned foremen departed for the front lines, less experienced workers took their place. Due to labor shortages, the new rank and file included women who were encouraged to take jobs outside of their homes for the first time. Other defense workers came from rural areas and were not familiar with the industrial workplace, let alone the heightened occupational hazards that came with defense production. To manufacture weapons and military vehicles, many defense jobs required working with chemicals, explosives, and other hazardous materials up close. In other plants, workers crowded new machinery into existing factories, making tight spaces between people and machines even more cramped.

Defense plants increasingly prioritized efficiency and productivity. To maximize production, they brought workers in for two to three shifts per day. Although manufacturing could continue around the clock, this left little time for maintenance. Working longer hours at a faster pace also strained older machines that had been quickly modified. To make matters worse, some companies became lax with safety code enforcement. Once they were trained for their jobs, many new workers still lacked safety training and workplace protections. These conditions compounded standard risks and created an even more hazardous environment for defense workers.

Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, News Bureau, ca. 1941-1945. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 535803), public domain.

The Cost of Efficiency

At the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, for instance, women took jobs as riveters and welders. Records from the shipyards’ first aid stations and local field hospitals accounted for 13,261 total fractures—mostly to the hands, feet, and ribs.[3] One woman fractured her skull after a 60-foot fall from the top deck of a hull. Women welders at the shipyard were also exposed to toxic vaporized metals like copper and zinc. While medical records documented the rates and types of traumas, occupational diseases, and nonoccupational problems that these women experienced, they do not provide insight into their well-being after the war. Some women made a full recovery, but it is likely that many others continued to experience complications for the rest of their lives.

Although women workers sustained many of the same severe injuries as their male counterparts, the federal government was primarily concerned about the increasing rate of injury and death among fighting age men. (Additionally, most of the male workforce at the Kaiser Shipyards was over the draft age or had already been deemed unfit for service.) Still, female workers were essential. With women in the workforce, the US could maintain its rapid pace of production and send more men off to the front lines.

Promoting Safety or Shame?

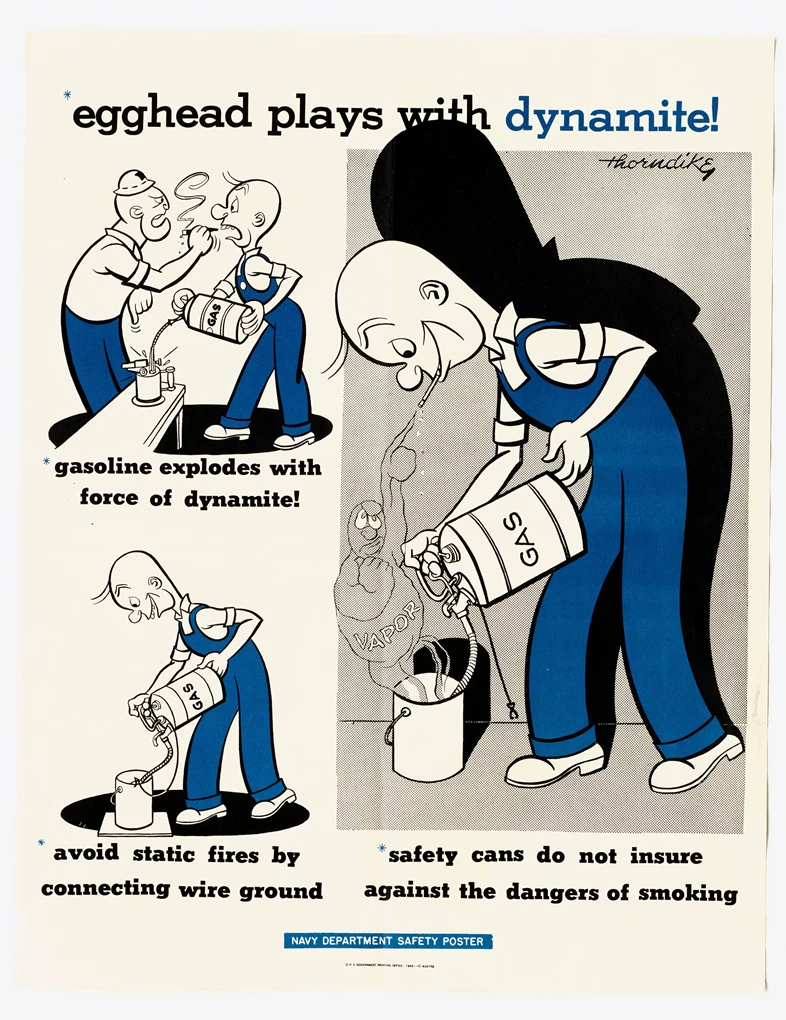

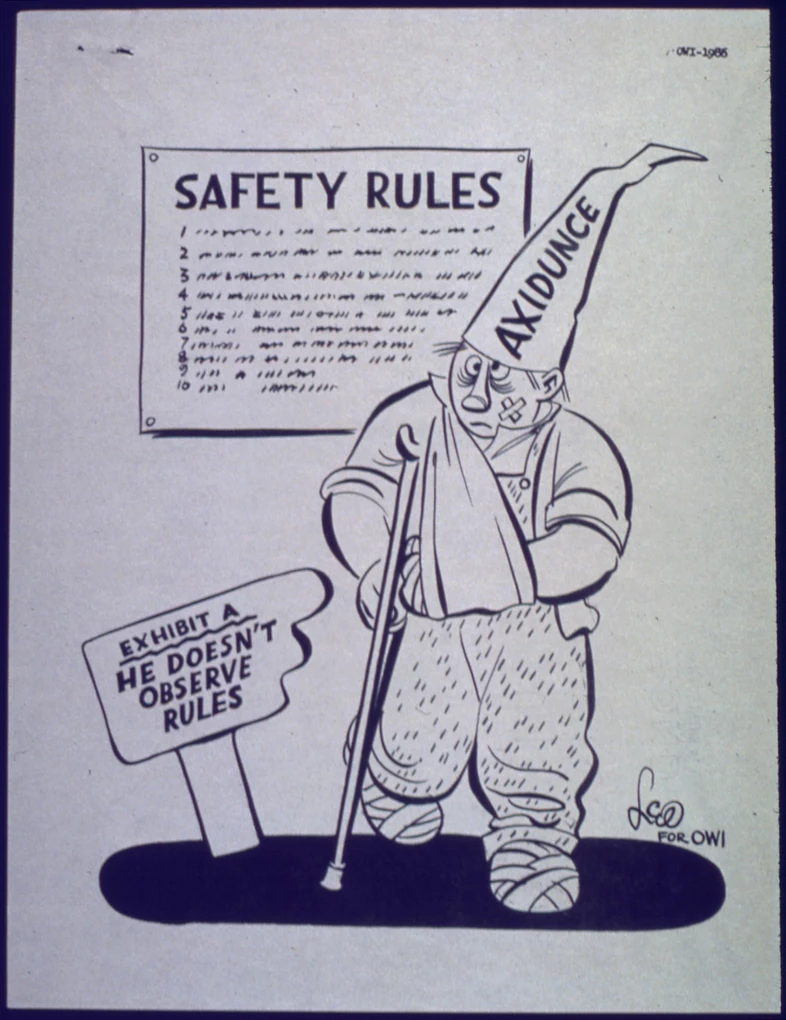

To reduce workplace accidents, the federal government partnered with private companies to organize safety campaigns. Instead of providing needed training or addressing workplace hazards, many initiatives placed the blame on workers. In 1942, for instance, the Allison Division of General Motors used the character “Otto Nobetter” to encourage safety measures at small defense plants in Chicago. Similar characters, such as “Axidunce” and “Egghead,” were also used to depict the consequences of carelessness at work.

Left image

“Eggmhead Plays with Dynamite" poster.

Credit: Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services, ca. 1941-1945. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 514204), public domain.

Right image

“Axidunce cartoon" poster. Text reads: "Safety Rules - Exhibit A. He doesn't observe rules."

Credit: Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services, ca. 1941-1945. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 513908), public domain.

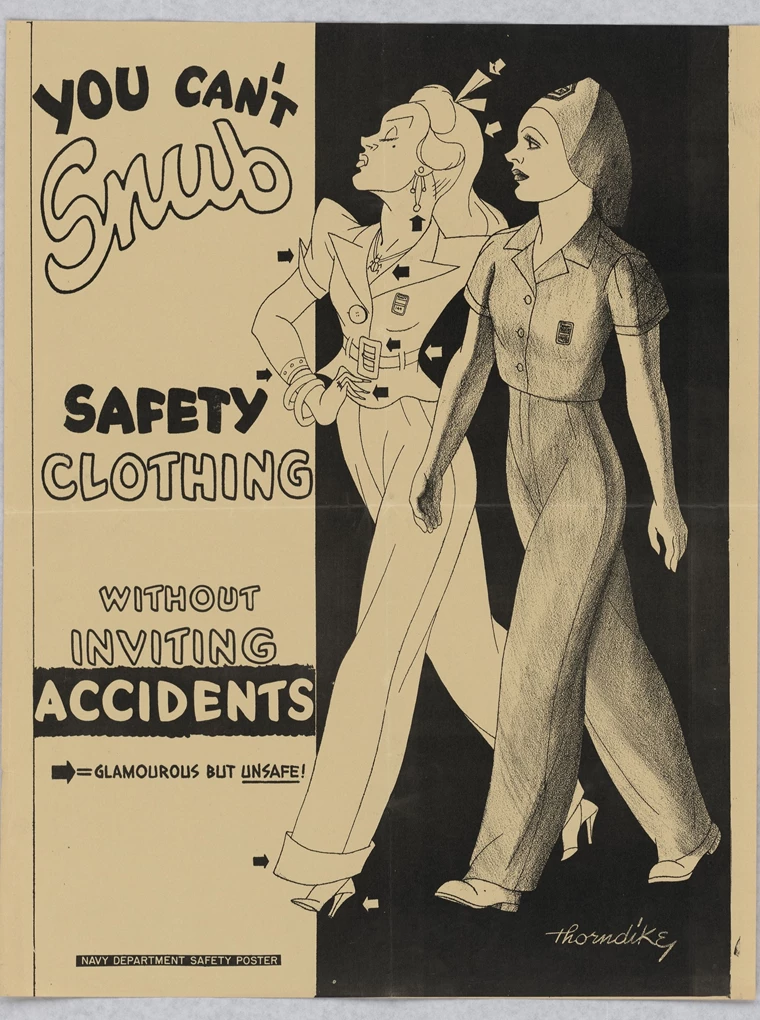

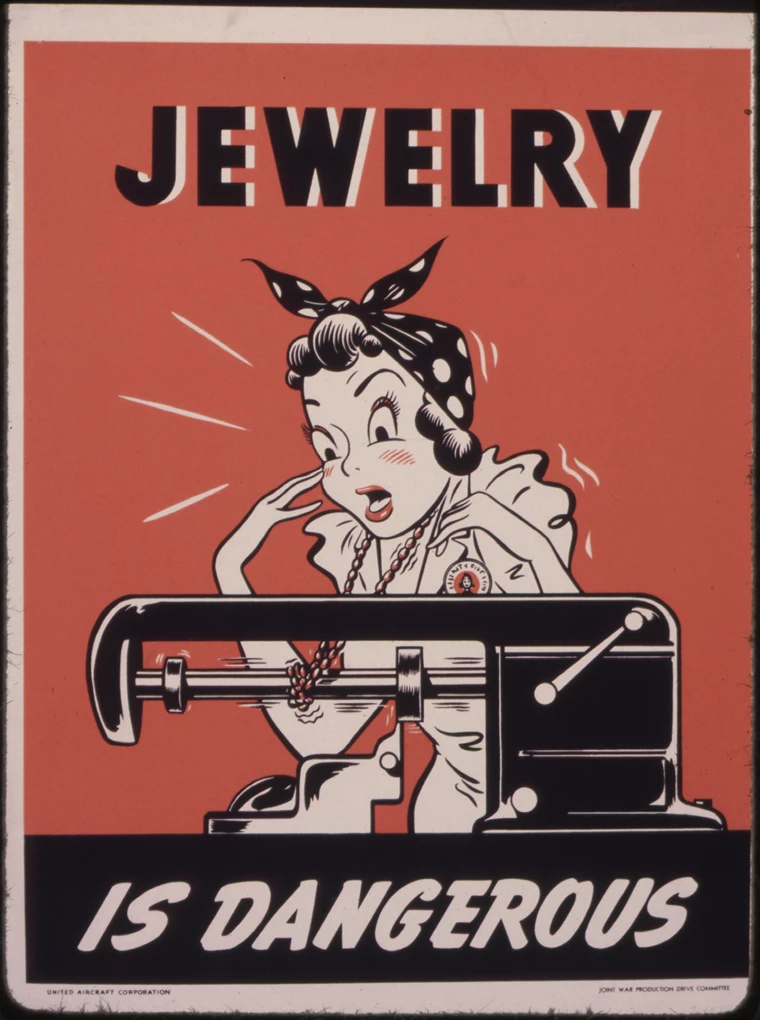

Other posters drew on gender stereotypes to portray women as vapid, vain, and more concerned with their appearance than practicality on the job. Although these depictions were intended to be comical, they instilled humiliation rather than humor. By emphasizing individual responsibility to prevent accidents, safety campaigns could redirect scrutiny from the unsafe conditions and culture of maximum efficiency that made the workplace dangerous. They also helped employers to divert attention from their financial responsibilities for workers’ compensation.

Left image

“You can’t snub safety clothing without inviting accidents...Glamorous but unsafe!” poster.

Credit: Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services, ca. 1941-1945. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 516218), public domain.

Right image

“Jewelry is dangerous” poster.

Credit: Office for Emergency Management, War Production Board, ca. 1942-1943. Courtesy of the National Archives. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 535336), public domain.

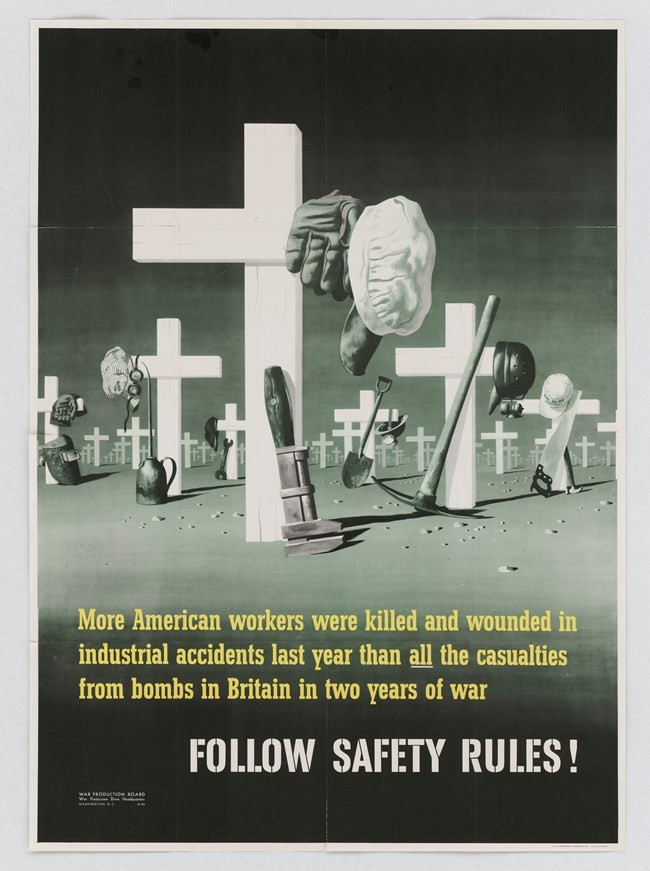

Office for Emergency Management, Office of War Information, Domestic Operations Branch, Bureau of Special Services, ca. 1941-1945. Courtesy of the National Archives (NAID: 514144), public domain.

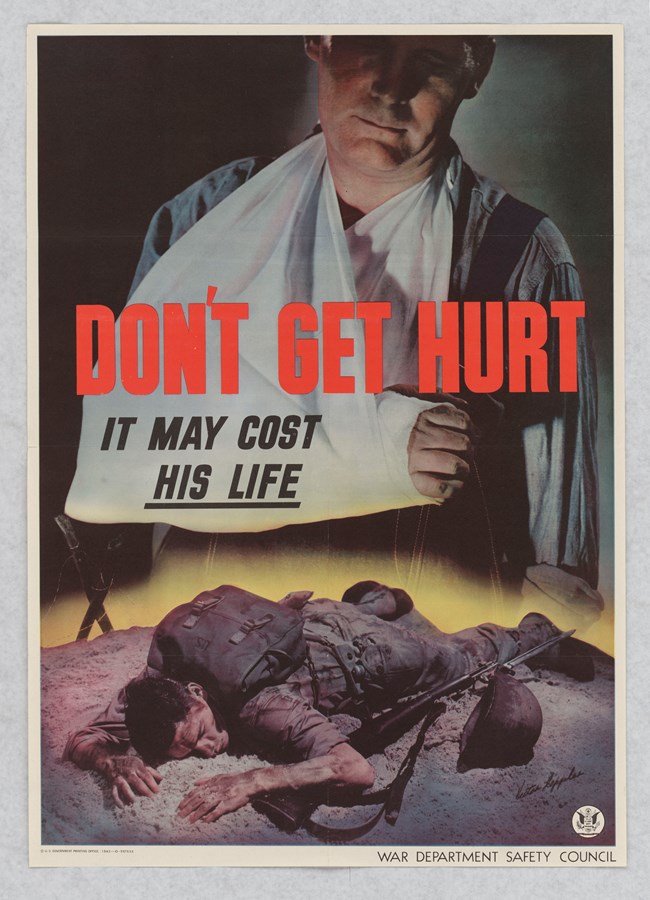

Patriotism and Productivity

Many occupational safety posters created a direct link between efficient (yet safe) home front production and victory on the battlefield. But injuries on the assembly line were not honored like injuries on the front lines. In fact, safety campaigns used patriotic fervor to publicly shame people who experienced accidents and were taken off the job. Imagery of battered soldiers and sayings like “Don’t get hurt—it may cost his life” reinforced the sense of urgency that defense production demanded.

Taking time off for recovery and losing a day of work compromised the total participation needed to win the war. By promoting negative beliefs about people with disabling injuries, these campaigns suggested that the inability to contribute was like failing to fulfill one’s patriotic duty. One poster read “Idle hands work for Hitler” to express that wasting time, materials, or labor was as bad as aiding and abetting the Axis Powers.

Although safety campaigns prioritized the war effort, getting hurt on the job also had economic stakes for individual workers and their families. The wages lost during recovery could be critical and workers’ compensation was rarely enough to keep someone out of poverty. After workers’ compensation was introduced during the 1910s and 1920s, many companies promoted the idea that disabled people were more susceptible to accidents and reinjury. During the interwar period, employers used concerns about compromised efficiency to justify the exclusion of workers with disabilities and to avoid responsibility for the costs associated with their accommodations and care.

Photo by Alfred T. Palmer, October 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USE6-D-006409 (b&w film neg.)

Conclusion

World War II eliminated some barriers to employment for workers with disabilities, but many non-disabled people still assumed that people with disabilities could not—and should not—hold jobs. Despite disabled people’s willingness and ability to contribute, workplace injuries were still treated like a burden and a disgrace. Additionally, some companies refused to pay for claims and denied responsibility if a disabled worker got hurt on the job.

Although most workplace injuries were only temporarily disabling, the occupational hazards of the defense industries contributed to the growing awareness of disability that accompanied World War II. Moreover, workers who did experience a permanent disability joined a growing number of disabled people who would continue to experience and challenge discrimination in the decades to come.

Consider This:

Imagine that you got hurt at work. Where would you turn for assistance? Who would be responsible for your care? How would you continue to pay your bills?

This article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Consulting Historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded through the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Andrew E. Kersten, Labor’s Home Front: The American Federation of Labor during World War II (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 166.

[2] Morris H. Hansen, comp., “Table No. 234: Estimated Number of Disabling Industrial Injuries, by Major Industry Group: 1943 to 1945,” Statistical Abstract of the United States, no. 67 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946), 217. The Bureau of Labor Statistics tallied deaths and permanent total disabilities together. One of the most deadly workplace incidents occurred in July 1944 at Port Chicago near San Francisco.

[3] Morris F. Collen, Bryan Culp, and Tom Debley, “Rosie the Riveter’s Medical Records,” The Permanente Journal 12, no. 3 (Summer 2008): 84-89.

Carlisle, Prince M. “Drive Begun to Cut Plant Accidents.” New York Times, April 12, 1942.

Collen, Morris F., Bryan Culp, and Tom Debley. “Rosie the Riveter’s Medical Records.” The Permanente Journal 12, no. 3 (Summer 2008): 84-89.

Hansen, Morris H., comp. Statistical Abstract of the United States, 217. No. 67. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946.

Jennings, Audra. “Disability and Industry.” The Human Machinery of War: Disability on the Front Lines and the Factory Floor, 1941-1945. Digital exhibit, The Ohio State University.

Kersten, Andrew E. Labor’s Home Front: The American Federation of Labor during World War II. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

McNutt, Paul V. “Our Greatest Waste.” New York Times. September 13, 1942.

New York Times. “Huge Fund Raised for Safety Drive: Movement to Eliminate Accidents in War Plants to be Largest in History.” January 3, 1943.

New York Times. "Knudsen Acclaims Our War Output: Production Well on Way, He Says in Telling Results of His 500-Plant Tour." September 12, 1942.

Petersen, Peter B. “Occupational Safety in Times of Haste: Lessons Learned from American Workers on the Home Front During World War II.” Journal of Managerial Issues 6, no. 4 (1994): 408–27.

Popular Mechanics. “Comic Model Depicts the Perils of Carelessness.” 78, no. 1 (July 1942): 65.

Rose, Sarah F. No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s-1930s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- ww2

- world war ii history

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- disability

- disability history

- labor history

- labor

- women's history

- developing the american economy

- defense production

- chicago

- illinois

- san francisco

- california

- rosie the riveter / wwii home front national historic park

- taas

Last updated: October 5, 2023