Part of a series of articles titled Disability and the World War II Home Front.

Article

Disabled Defense Workers on the World War II Home Front

During World War II, many new job opportunities opened to people with disabilities. To fill vacancies left by drafted and enlisted servicemen, the War Manpower Commission’s US Employment Service looked to adults who were exempt from or deemed "unfit" for military service. These groups included women, men over 45 years old, and people with a wide range of physical impairments. Some companies like Ford Motor Company and Firestone Tire and Rubber Company had already hired disabled employees (especially veterans) for many years. For other employers, World War II marked the first time that they hired people with disabilities.

International Center for the Disabled Records (MS 792), Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

Federal-state vocational rehabilitation (VR) programs played a significant role in the recruitment, placement, and training of disabled workers.[1] As part of these programs, job candidates were subjected to interviews and tests, that could be invasive and were often arbitrary, before employers would consider them. Some of these measures were strictly focused on job preparedness. Others, however, took a more medical approach, including physical exams and mental tests, that focused on people’s individual condition, rather than the environment and attitudes which made the workplace inaccessible.[2] Despite these hurdles, many people with disabilities were eager to do their part.

Many Americans with disabilities became frustrated when they were barred from military service and someone else decided what they could and couldn’t do. For instance, Eric Malzkuhn recalled: “I felt a little injustice. I wanted to join, but I was told that I couldn’t because I’m deaf. Hearing people who didn’t want to join were told they had to, but many deaf people felt that they could serve. If some hearing people wanted to get out, we would have been happy to take their place.”[3] Malzkuhn followed through and wrote to the Army suggesting the creation of a special division for deaf people. Although nothing came of Malzkuhn’s proposal, he and other disabled civilians contributed in other ways.

International Center for the Disabled Records (MS 792), Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

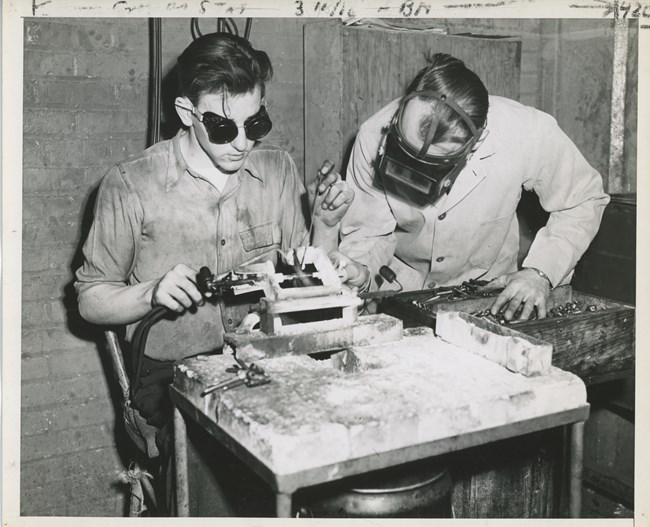

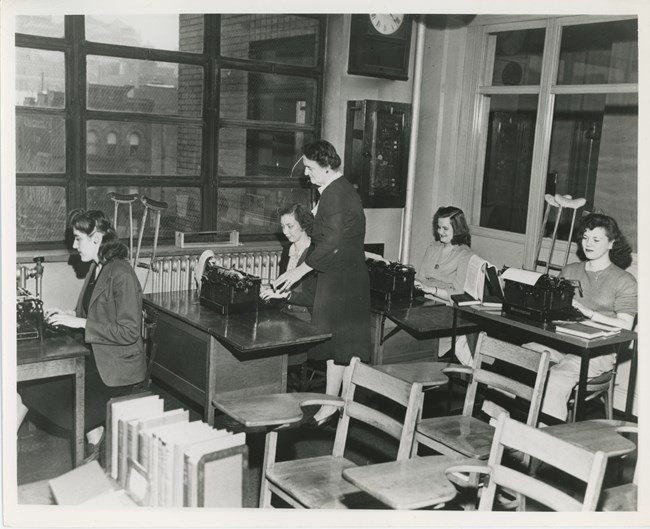

To encourage the hiring of disabled workers, the US government had to counteract what one reporter called “the erroneous belief that physically impaired workers [were] less efficient than the able-bodied.”[4] The War Department released promotional materials, including films, that illustrated the range of jobs that (primarily physically) disabled workers could have. The film Employing Disabled Workers in Industry, for instance, featured several people with amputated or deformed limbs. They worked as milling machine operators, roller bearing machinists, carpenters, and welders. Many of these roles involved the use of an artificial hand or other self-made devices.

Other individuals, including a sewing machine operator and secretary, performed tasks that required a high degree or precision and skill without assistive technology. The film also depicted some of the assessments (such as tests for hand-eye coordination, dexterity, and recognizing and assembling familiar patterns) that job candidates needed to pass. By May 1942, the New York Times estimated that 3 million “so-called disabled men and women, the blind, crippled, cardiac, tuberculous, or deaf” had been employed in war industries.[5]

International Center for the Disabled Records (MS 792), Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

State VR staff also followed up with employers to evaluate disabled workers’ efficiency. In 1943, the Vocational Rehabilitation Division of the US Office of Education asked over 100 companies around the country to compare the performances of disabled and non-disabled workers based on rate of production, absenteeism, turn-over, and accidents. Employers reported that disabled workers performed equally as or better than their non-disabled peers in all categories. In Springfield, Massachusetts, for instance, managers at both the Springfield Ordnance District and Indian Motorcycle Company applauded the Massachusetts VR department for placing such successful hires.[6] Clifford E. Davis, an employment manager at Indian Motorcycle Company attested:

“From what information is available, these workers compare very favorably with the able-bodied men on the same type of work. They seem, as a rule, to be very conscientious. Both Miss King and yourself have been of assistance in selecting the person best suited to our needs, and as a result, your selections have been satisfactory.”[7]

In fact, many employers noted that workers’ impairments offered certain advantages. In Kenosha, Wisconsin, for instance, a US Employment Service district manager expressed that deaf people were better workers “because they cannot be easily distracted from their tasks.”[8] Employers at the Lighthouse of the New York Association for the Blind similarly claimed that blind workers’ use of Braille enhanced their sense of touch and made them more adept at sorting rivets of eight different sizes and shapes.[9] Others observed that people with disabilities were more cautious than their non-disabled peers and less likely to get hurt at work.

Despite employers’ satisfaction with disabled workers, the end of World War II marked another shift. As servicemen returned to the civilian workforce, wartime hires were expected to step aside. World War II illustrated the possibilities of reasonable workplace accommodations across the nation and revealed that one of the biggest barriers to more inclusive hiring was employers’ bias. Moreover, VR programs remained important, particularly as disabled veterans readjusted to civilian life.

Learn about some of the many places where disabled people worked during World War II.

Consider This:

When has someone placed a limitation on you? How did you respond? Have you ever placed a limitation on someone else? How did they respond?

This article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Consulting Historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Rehabilitation Continuing Education Program, Region 7, “Module 1: History of Vocational Rehabilitation,” The Public Mandate: A Federal Overview (University of Missouri, 2004). Public rehabilitation programs first began to appear after World War I, particularly to support veterans. The Soldiers Rehabilitation Act of 1918 established the first federal VR program. Congress’s passage of the Barden-LaFollette Act in 1943 made a wider range of people eligible for vocational rehabilitation, expanded the types of services that could be offered, and increased funding for maintenance and certain services. For the first time, the blind and people with intellectual disabilities could qualify for vocational rehabilitation services.

[2] Perspectives on disability have changed a lot over time, but mostly follow the charity, medical, and social/human rights models of disability.

[3] Deaf People World War II, “Eric Malzuhn,” from Deaf Mosaic, hosted by Gil Eastman and Mary Lou Novitksy, YouTube video, 0:03:44.

[4] Burton Lindheim, “’Disabled War Workers,’” New York Times, May 31, 1942.

[5] Federal Security Agency, US Office of Education, Vocational Rehabilitation Division, Vocational Rehabilitation: The Employment Efficiency of Physically Impaired Workers (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1943), 3.

[6] The Secretary of the Interior designated Springfield, Massachusetts as an American World War II Heritage City in 2022.

[7] “Letter from Clifford E. Davis to Ernest Swift,” Vocational Rehabilitation, 33.

[8] “Handicapped Getting Jobs,” Kenosha News, December 16, 1943.

[9] Anne Petersen, “Deaf and Blind Fill War Posts: Operate Power Machines, Work in Leather, Metal, and Radio Board Wiring,” New York Times, June 28, 1942.

Deaf People World War II. “Eric Malzkuhn.” From Deaf Mosaic, hosted by Gil Eastman and Mary Lou Novitksy. YouTube video, 0:03:44.

Federal Security Agency, US Office of Education, Vocational Rehabilitation Division. Vocational Rehabilitation: The Employment Efficiency of Physically Impaired Workers. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1943.

Kenosha News. “Handicapped Getting Jobs.” December 16, 1943.

Lindheim, Burton. “Disabled War Workers.” New York Times. May 31, 1942.

McNutt, Paul V. “Our Greatest Waste.” New York Times. September 13, 1942.

Nielsen, Kim E. “We Don't Want Tin Cups: Laying the Groundwork, 1927-1968.” In A Disability History of the United States. Revisioning American History. Boston: Beacon Press, 2012.

Petersen, Anne. “Deaf and Blind Fill War Posts: Operate Power Machines, Work in Leather, Metal, and Radio Board Wiring.” New York Times. June 28, 2942.

Rose, Sarah F. “‘Crippled’ Hands: Disability and Working Class History.” Labor Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 2, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 27-54.

Rose, Sarah F. No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s-1930s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Rehabilitation Continuing Education Program, Region 7. “Module 1: History of Vocational Rehabilitation.” The Public Mandate: A Federal Overview. University of Missouri, 2004.

Rochester Institute of Technology. Deaf People and World War II. Accessed July 12, 2023.

Last updated: March 25, 2024