Part of a series of articles titled Disability and the World War II Home Front.

Article

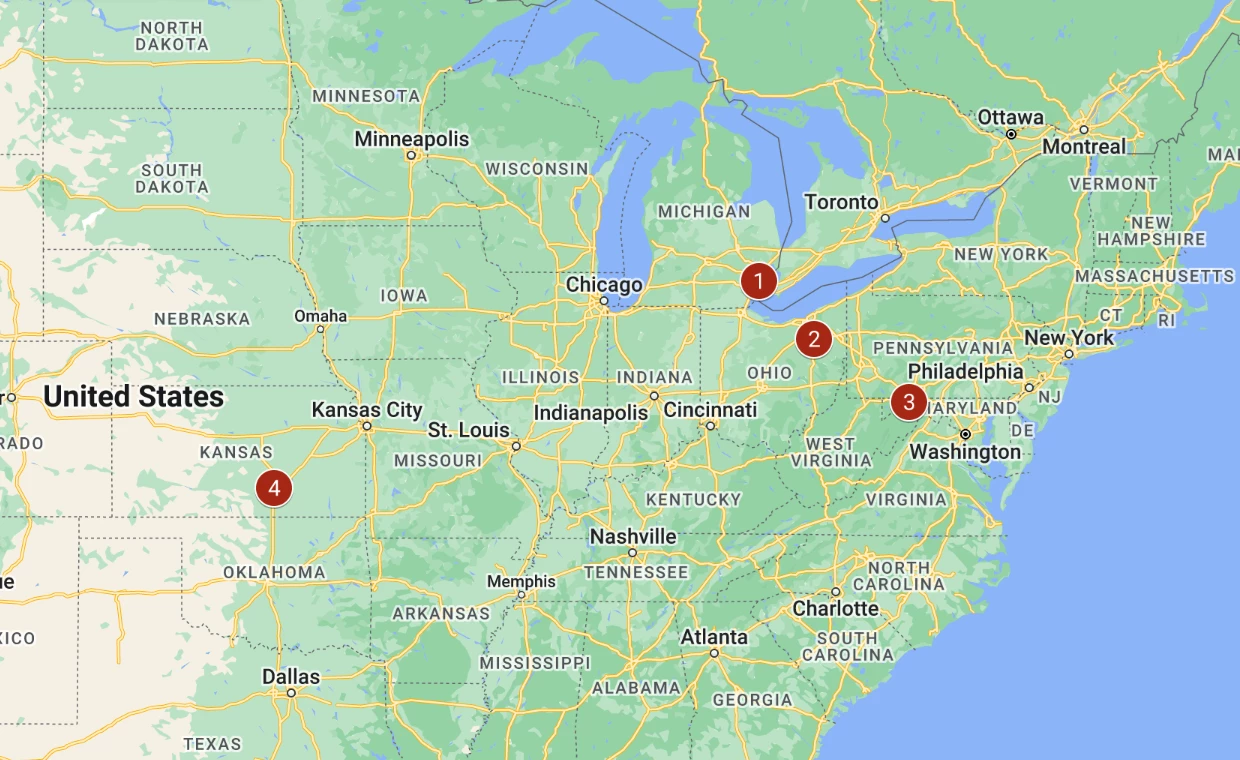

Places of Disabled Defense Workers on the World War II Home Front

This article highlights a few of the many job opportunities that opened to people with disabilities during World War II.

Courtesy of Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

Ford Motor Company River Rouge Plant

The Ford Motor Company was a leader in the hiring of disabled workers since the 1900s and 1910s. During this period, other companies used mechanization as an excuse to exclude workers with physical and sensory disabilities and chronic illnesses to maximize efficiency. Henry Ford, on the other hand, realized that machinery could be used to expand people's abilities by making work easier and more specialized.

Instead of focusing on workers’ physical limitations, doctors in Ford’s medical department conducted physical examinations to place disabled workers in jobs appropriate for their capabilities. By 1919, over 9,000 of the company’s 33,000 total employees were people with disabilities. Although job opportunities for disabled workers declined between the world wars, many of Ford’s disabled employees were World War I veterans.

In addition to workers with disabilities, Ford also hired other groups of people that were often barred from jobs, including African Americans, women, felons, and men over 70. Henry Ford was motivated by his beliefs about social efficiency and the moral value of work and his distaste for waste and dependence. The company’s policy stated:

“No company regards such employment as charity or altruism. All our handicapped workers give full value for the wages and their tasks are carried out with absolutely no allowances or special considerations. Our real assistance to them has been merely the discovery of tasks which would develop their usefulness.”

Courtesy of Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

During World War II, 80% of all industries hired people with disabilities. The Ford Company alone hired 11,000 disabled people and offered them the same rate of pay as their non-disabled peers. Ten percent of them were blind, including Sylvester Rypkowski and his service dog Blackie. Unlike other employers that were hesitant to hire people with disabilities, Ford publicized his diverse workforce in local and regional newspapers. Some of this coverage featured Blackie joining Rypkowski to get “pawprinted” for identification.

At Ford's River Rouge plant, the company also employed 112 workers with epilepsy in jobs that did not require operating machinery or climbing. The company noted that employers needed to place disabled workers in jobs suited to their abilities with appropriate accommodations, rather than focusing on what their physical limitations.

The Ford River Rouge Complex was designated as National Historic Landmark District in 1978. MotorCities National Heritage Area also commemorates the history of the automobile industry in central and southeast Michigan.

Goodyear and Firestone Tire and Rubber Companies

Left image

Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company Plant in Akron, Ohio, ca. 1930-1945.

Credit: Courtesy of Boston Public Library, The Tichnor Brothers Collection. No known restrictions.

Right image

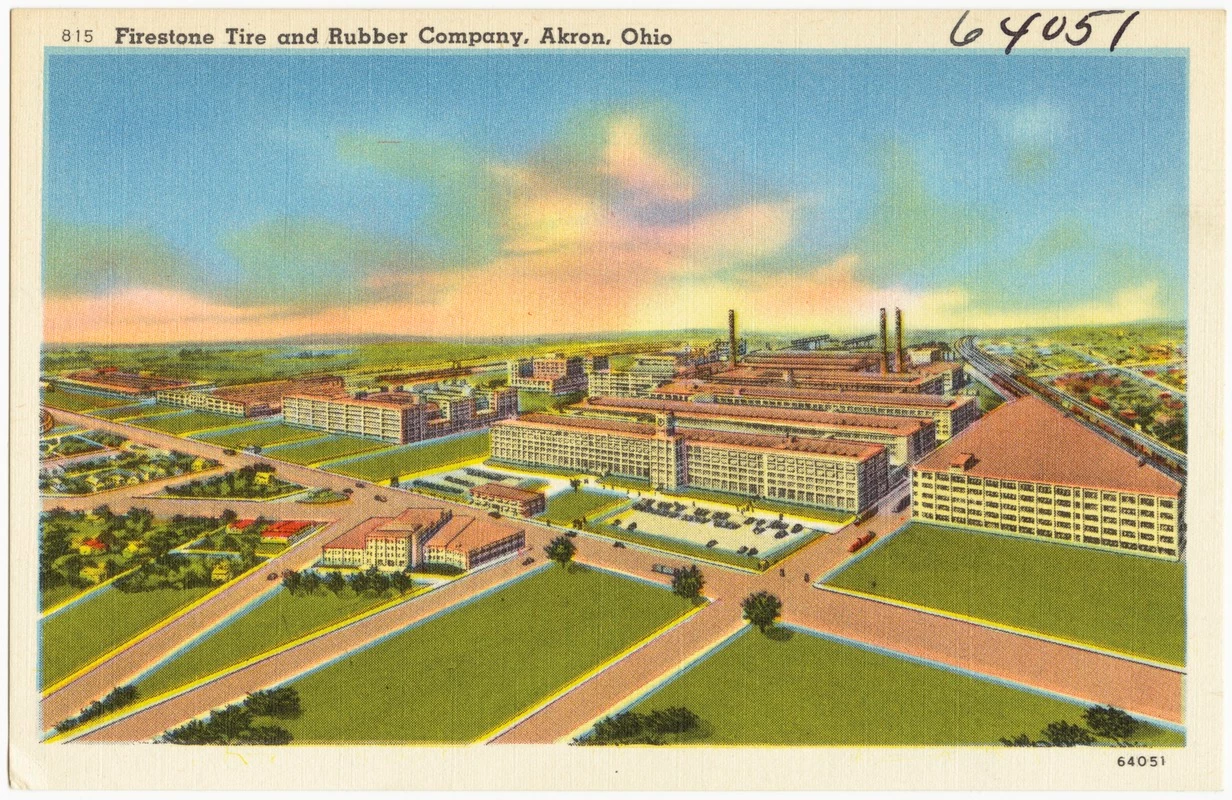

Firestone Tire and Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio, ca. 1930-1945.

Credit: Courtesy of Boston Public Library, The Tichnor Brothers Collection. No known restrictions.

Akron, Ohio saw one of the largest surges in the wartime employment of deaf people. To support defense production during World War II, Firestone and its main competitor Goodyear hired around 1,000 deaf workers. This was largely due to the efforts of Benjamin Schowe, Sr., a labor economics specialist at Firestone. To identify potential war workers, he reached out to vocational rehabilitation training schools and programs around the country. Job postings also appeared in nationally circulated publications, such as the National Fraternal Society of the Deaf and the Ohio Chronicle.

Firestone and Goodyear had also hired deaf people to address labor shortages during World War I. However, both companies were quick to lay them off during the postwar recession. Once the economy stabilized, Firestone and Goodyear reverted to hiring non-disabled, permanent residents of Akron until the onset of World War II.

During World War II, both companies featured deaf workers in films about wartime production. Goodyear highlighted a group of deaf women who signed to communicate at work. Firestone’s film also showcased people who were blind, deaf, and mobility-impaired on the production line.

In Akron, deaf people formed their own clubs, religious groups, sports teams, and other community institutions. At home, they also participated in canned food and scrap drives, donated blood, and knit socks and other items for soldiers. Like their jobs in the defense industries, these activities provided additional ways for community members to contribute to civilian mobilization on the World War II home front.

The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company Headquarters was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. The Firestone Tire and Rubber Company Building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2014.

Ann Rosener, US Office of War Information, 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, public domain.

White Engineering Company

In Baltimore, Maryland, White Engineering Company hired young men with physical disabilities to prepare parts for airplane motors. These workers had a range of responsibilities, from inspecting parts to operating machinery, such as the lathe, band saw, and drill press. Most of them had limited use of their arms or legs due to amputated limbs or polio.

White Engineering also subcontracted teenaged girls and young women at the Maryland League for Crippled Children. Some of them were tasked with removing rough edges from Y-shaped parts for engines by hand. Others were responsible for painting the parts afterwards. Because many of these women had weakened or paralyzed limbs due to polio or arthritis, these tasks allowed for standing or sitting as needed.

The Bell Tower Building, also known as the Allegany County League for Crippled Children Building, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.

Courtesy of the Wichita Beacon, Newspapers.com.

US Civilian Defense Corps, Deaf Auxiliary Fireman Unit

Workers with disabilities also took on additional wartime responsibilities outside of defense manufacturing. In Wichita, Kansas, for instance, about twenty deaf men organized an auxiliary fireman unit in May 1942. According to the Wichita Beacon, it was the only “totally deaf auxiliary fireman unit in the United States Citizens Defense Corps.”[1] The group was created to improve relations between deaf and hearing people in Wichita, as well as to expand equal opportunities for deaf people.

Wichita’s fire chief and captain worked with a sign language interpreter to train the men in first aid, fire defense, gas defense, hose handling, ladders, and other skills. Many of the deaf auxiliary firemen assumed these duties in addition to their jobs at local defense plants, where some even worked double shifts. The Wichita Beacon described one firefighter who attended weekly drill after only three hours of sleep between shifts.

Because of their hard work, dedication, and attentiveness, the deaf auxiliary firemen received accolades from the local community as well as national attention. In September 1943, the auxiliary unit presented an exhibition at the state firemen’s association school. The group also attracted the attention of the Red Cross, which requested information about the first aid instruction that the men received. In addition to coverage in the local press, the deaf auxiliary fireman unit was also recognized nationally. In February 1944, the Civilian Front (a national weekly newspaper for civil defense) published a feature story about the unit.

The Secretary of the Interior designated Wichita, Kansas as an American World War II Heritage City in 2022.

Consider This:

Think about a different job or task you've performed in the past. What made or didn't make the experience meaningful?

This article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Consulting Historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] “Totally Deaf Firemen Make Fine Record,” Wichita Beacon, July 22, 1943.

Gallaudet University. “Mosaic Memoirs.” Deaf Mosaic. Episode 607. Hosted by Gil Eastman and Mary Lou Novitksy. Aired 1990. Gallaudet University Video Library, 2007, website.

Gallaudet University National Deaf Life Museum. “Community Building.” History Through Deaf Eyes. 2004.

Kannapell, Barbara M. “The Forgotten Americans: Deaf War Plant Workers during World War II.” NADmag. February/March 2002.

Lindheim, Burton. “Disabled War Workers.” New York Times. May 31, 1942.

McNutt, Paul V. “Our Greatest Waste.” New York Times. September 13, 1942.

Nielsen, Kim E. “We Don't Want Tin Cups: Laying the Groundwork, 1927-1968.” In A Disability History of the United States. Revisioning American History. Boston: Beacon Press, 2012.

Rose, Sarah F. “‘Crippled’ Hands: Disability and Working Class History.” Labor Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 2, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 27-54.

Rose, Sarah F. No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s-1930s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

“Use of Handicapped Workers in War Industry.” Monthly Labor Review 57, no. 3 (1943): 435–443.

Wichita Beacon. “Totally Deaf Firemen Make Fine Record.” July 22, 1943.

Wichita Eagle. “Usual and Unusual: Praises Wichita Group.” February 26, 1944.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- ww2

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- disability

- disability history

- labor history

- defense production

- civilian defense

- dearborn

- michigan

- akron

- motorcities national heritage area

- ohio

- baltimore

- maryland

- wichita

- kansas

- awwiihc

- american world war ii heritage city program

- taas

- civil defense

- vocational rehabilitation

Last updated: October 5, 2023