Part of a series of articles titled Disability and the World War II Home Front.

Article

Unfit for Service: Physical Fitness and Civic Obligation in World War II

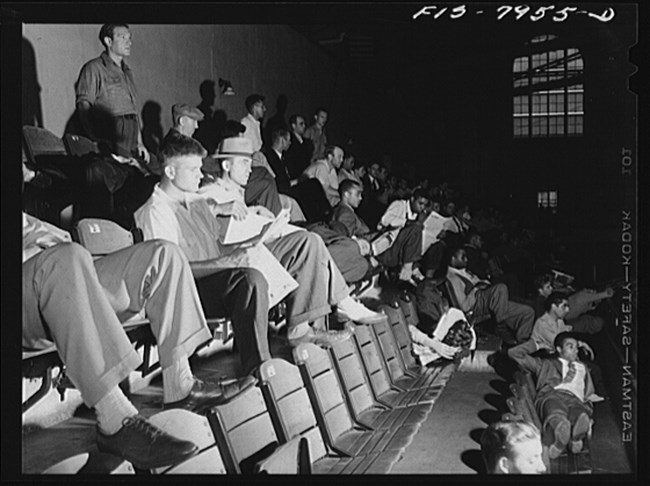

Left image

Swedish American selectee in Minnesota takes a physical examination as he is inducted into the US Army.

Credit: Jack Delano, Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information, April 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, public domain.

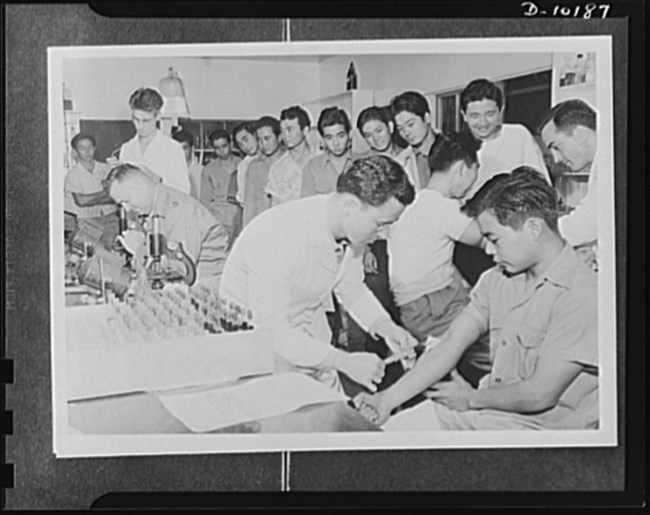

Right image

Swedish American selectee in Minnesota takes a physical examination as he is inducted into the US Army.

Credit: Jack Delano, Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information, April 1942. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, public domain.

World War II brought widespread attention to health, physical fitness, and disability across the United States. As part of the military’s mobilization, all drafted and enlisted men and enlisted women had to undergo physical and psychiatric examinations to assess their readiness and fitness for war. Over the course of World War II, about 19 million American men were drafted, but nearly half of them didn’t make the cut.[1] This article explores some of the reasons behind the draft’s rejection rate of over 40%. It also discusses some of the factors that disqualified people from military service.

Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, public domain.

Separating the "Fit" and "Unfit"

Between World Wars I and II the United States had a relatively small military. The Army was made up of less than 200,000 soldiers and officers, while the Navy had less than 100,000 active-duty sailors.[2] The government worried that there wouldn’t be enough American servicemen to successfully fight and win World War II. For full mobilization, the military needed to induct 10 million men between 1940 and 1945.[3] To achieve this goal, Congress passed the Selective Training and Service Act in September 1940. This law required all fighting age men to register for a military draft. It also authorized military officials to determine which men were best for different wartime roles, such as combat or defense production.

The military also tried to exclude groups that officials believed would weaken the military or drain time and resources. These concerns led to the disqualification of many people with a wide range of acquired and congenital conditions.[4] After World War I, the federal government became responsible for over $1 billion in veterans' disability claims.[5] The military hoped to avoid a repeat situation after World War II. To prevent men who were likely to develop disabilities from eventually becoming eligible for veterans’ benefits, the military tried to keep them from ever being inducted. New physical and psychiatric tests provided a way to identify pre-existing conditions and illnesses.

Draft boards used the test results to assign drafted and enlisted men to one of four major divisions. Each classification consisted of a number (or Roman numeral) and a letter. For instance, those assigned 1-A were “available for military service.” Most men in Class 2 were generally deferred due to jobs in war production or agriculture. On the other hand, men in Class 3 were exempted because they had dependents.[6] Class 4-F referred to men who were deemed “unfit for service due to physical, mental, or moral reasons.”[7] The military rejected these men altogether.

Farm Security Administration, Office of War Information Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, public domain.

Standardizing Screening

High physical fitness standards contributed to the draft's rejection rate of over 40%. The military faced intense pressure to screen as many recruits as they could as quickly as possible. This caseload proved too burdensome for Army doctors and facilities to tackle on their own. The military tasked 6,500 local draft boards and 30,000 (mostly civilian) physicians with some of the initial assessments.[8] Even with their help, it was impossible to provide in-depth evaluations for every recruit.

To provide consistency across exams, the military developed "objective" qualification standards. These included basic measurements for height, weight, pulse rate, and blood pressure. Although the military accepted these measurements as scientific, applying them on a national scale involved a high degree of inconsistency. The standards provided a one-size-fits-all model. They inflated the importance of certain qualities and overlooked others. Due to concerns about stamina and strength, for instance, height and weight often acted as stand-ins for a recruit's overall physical fitness.

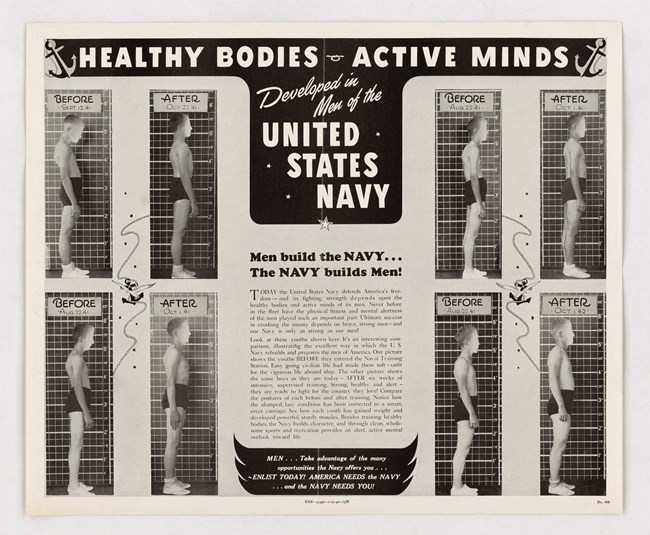

Qualification standards also shifted over the course of the war, making it difficult for local draft boards to keep up. Initially, minor factors like number of teeth, poor eyesight, flat feet, and venereal disease could disqualify recruits. But in August 1942, the military began to accept men with “remediable defects.” Through Selective Service rehabilitation programs, recruits received glasses, had dental work (such as filling cavities and getting fitted for dentures), and underwent treatments for syphilis. Many 4-F men also worked toward reclassification on their own. Some purchased kits to "correct" colorblindness. Others tried to gain weight or took classes to improve low intelligence or illiteracy scores.

Age requirements also changed. Initially, all men between 21 and 36 years of age had to register for the draft. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the registration range expanded to 18 through 64 years of age. But only men between the ages of 18 through 45 were actually drafted. Military officials worried that recruits younger than 18 would be too physically weak and immature. On the other hand, men over 45 were more likely to have physical limitations, established careers, or large families to provide for. In the short term, recruiting men who were fathers would be disruptive to their families on the home front. In the long term, the military risked financial responsibility for a father's wife and children if he acquired a total disability or died.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513515).

"Unfit" and Ineligible

Despite the goal to provide objectivity, examiners could apply screening standards in biased ways. Taking psychiatric and environmental factors into account provided officials with a way to exclude certain groups from military service. This led to the disqualification of many men who were African American, homosexual, or both.

During World War II, military authorities began to treat homosexuality as a psychiatric issue.[9] Psychiatrists believed an “underdeveloped brain” could cause homosexuality. If people’s brains had not fully matured, they could not control their sexual impulses. Moreover, military and medical authorities believed that gay men's "underdevelopment" manifested as feminine physical characteristics. They worried that gay men would be too weak to keep up with the rigors of military service. Officials also assumed that the presence of gay men would disrupt morale.[10] Even if gay GIs did not act on their desires, officials believed that they still posed the danger of potentially doing so. Authorities also believed that straight soldiers would target and ridicule their gay peers. To avoid this, officials chose to disqualify gay men from military service.

Efforts to identify gay recruits were often invasive and humiliating. During interviews, examiners required men to strip naked and answer questions about their sexuality. They looked for recruits who showed discomfort or self-consciousness during this process. Officials believed that concern about appearing unmanly was a sign of "homosexual tendencies."[11]

Some officials did not want African Americans to serve alongside white troops. To justify their exclusion, authorities tried to claim that African Americans were inferior to other races and would make poor combat soldiers as a result.[12] Others expressed concern that Black soldiers would not adjust well to army life. To provide evidence for African Americans’ “inferiority,” some officials relied on racial stereotypes. They claimed that lack of access to schooling, healthcare, and jobs were signs of deficiency among African Americans.[13] Examiners failed to recognize that racial discrimination was the root cause for these experiences. Although over one million Black men and women were successfully inducted into the armed forces, they continued to face racism. However, these conditions also motivated African American civilians and soldiers to campaign against discrimination in the military and at home.

Disqualification from military service had real economic impacts. Excluding African Americans, gay men and women, and people with disabilities also made it impossible for them to qualify for veterans' benefits. The GI Bill of Rights made it easier for veterans to get a college education or become homeowners. Although the draft required all fighting age men to register, discriminatory screening processes prevented members of already marginalized groups from accessing these economic benefits.

Consider This:

When have you encountered standards in your life? What qualities or ideas did they promote? What qualities or ideas did they discourage?

This article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, Consulting Historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Rachel Louise Moran, “Men into Soldiers: World War II and the Conscripted Body,” in Governing Bodies: American Politics and the Shaping of the Modern Physique (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 64.

[2] Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II, twentieth anniversary edition with foreword by John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 1.

[3] Moran, “Men into Soldiers,” 67.

[4] These conditions included mental disorders, gastrointestinal issues, neurological disorders, musculoskeletal conditions (such as deformed or amputated limbs), endocrine disturbances (such as thyroid conditions and diabetes), tumors, and infectious diseases (including influenza and pneumonia).

[5] Tiffany Leigh Smith, “4-F: The Forgotten Unfit of the American Military during World War II” (Master’s Thesis, Texas Woman’s University, 2013), 30.

[6] The military tried to keep families intact for as long as possible. They allowed men with family responsibilities to their wives, children, or their parents (3-A) to defer, especially if military service would place an “undue burden” on those dependents. Other subcategories in Class 3 referred to men who had dependents and worked in agriculture (3-B) or war production (3-C).

[7] Others in Class 4 included men were classified as “unavailable for service” if they were over the fighting age (4-A), certain government officials (4-B), not US citizens (4-C), religious ministers (4-D), or conscientious objectors in civilian work (4-E).

[8] Moran, “Men into Soldiers,” 74.

[9] Before World War II, the military viewed homosexual activities as perverse and punished people for engaging in them. Treating homosexuality as a psychiatric disorder meant that the military could define individual people as “mentally ill” even if they did not engage in homosexual activities. It is likely that this screening process also excluded other members of the LGB community in addition to gay men and lesbians.

[10] Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire, 15.

[11] Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire, 16. Psychiatrists believed that signs of homosexuality could appear as small personality traits or tendencies to act abnormally.

[12] Margarita Aragon, “‘Deep-seated Abnormality’: Military Psychiatry, Segregation, and Discourses of Black ‘Unfitness’ in World War II,” Men and Masculinities 22, no. 2 (2019): 218.

[13] Aragon, “‘Deep-seated Abnormality,’” 217.

Aragon, Margarita.“‘Deep-seated Abnormality’: Military Psychiatry, Segregation, and Discourses of Black ‘Unfitness’ in World War II.” Men and Masculinities 22, no. 2 (2019): 216-235.

Bérubé, Allan. Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II. Twentieth anniversary edition with foreword by John D’Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Canaday, Margot. “‘With the Ugly Word Written across It’: Homo-Hetero Binarism, Federal Welfare Policy, and the 1944 GI Bill.” In The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Davis, Michael M. “How Healthy Are We?” New York Times. February 22, 1942.

Foster, William B., Robert S. Anderson, and Charles M. Wiltse. Physical Standards in World War II. Prepared and published under the direction of Leonard D. Heaton. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, 1967.

Goldstein, Marcus S. “Physical Status of Men Examined through Selective Service in World War II.” Public Health Reports (1896-1970) 66, no. 19 (1951): 587-609.

Jefferson, Robert F. “‘Enabled Courage’: Race, Disability, and Black World War II Veterans in Postwar America.” Historian 65, no. 5 (2003): 1103-1121.

McNutt, Paul V. “Our Greatest Waste.” New York Times. September 13, 1942.

Moran, Rachel Louise. “Men into Soldiers: World War II and the Conscripted Body.” In Governing Bodies: American Politics and the Shaping of the Modern Physique, 64–83. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Nielsen, Kim E. “We Don’t Want Tin Cups: Laying the Groundwork, 1927-1968.” In A Disability History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2012.

Rose, Sarah F. No Right to Be Idle: The Invention of Disability, 1840s-1930s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Smith, Tiffany Leigh. “4-F: The Forgotten Unfit of the American Military during World War II.” Master’s Thesis, Texas Woman’s University, 2013.

Last updated: February 19, 2025