Last updated: August 24, 2022

Article

Places of Healing: Hotels Join the World War II Home Front Effort

Courtesy of Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Leading up to World War II and into the first few years of fighting, military officials moved to expand the military healthcare system. They knew that they would soon need to accommodate thousands of soldiers training stateside and fighting overseas. The US Army especially wanted to expand their General Hospital system. These large hospitals were able to receive patients from a wide area and provide specialized care. Military staff knew that battle casualties would soon overtax their current infrastructure and sought to expand medical care as soon as possible.

The US Army was hesitant to build new hospital complexes due to the resources and time required to build. They also knew that after the war, they would likely not need as many hospitals to care for a peacetime army. For these reasons, the US Army sought out civilian buildings to occupy for the duration of the war that could be easily returned to civilian use afterwards. Hotels fit this purpose well due to their large number of rooms, and elevators that allowed easy transport of patients and equipment. Hotels also tended to have amenities like pools available for rehabilitation and recreation.

Public domain. Courtesy National Library of Medicine.

Due to wartime demands like fuel rationing, visitation was down at hotels. Without vacationers, hotels needed another way to produce income. Military contracts allowed hotels to survive the lean years of the war and reopen to the public afterwards. Hotels across the country signed over their facilities to the Army, turning over some of the finest resorts in the country to the war effort.

In 1933, the federal government began recording architecture, engineering, and landscapes in the United States through Heritage Documentation Programs. The program used to record buildings is called the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), and many of these records are available for online viewing on the Library of Congress website. Using photos, measured drawings, and written histories, we are able study a wide variety of structures, even if they are demolished after being recorded.

Hundreds of buildings were taken over by the military for use as hospitals and other purposes for the duration of World War II.[1] This article highlights five well-documented examples of hotels that were transformed into US Army General Hospitals. All five hotels have been surveyed by HABS.

Public domain. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

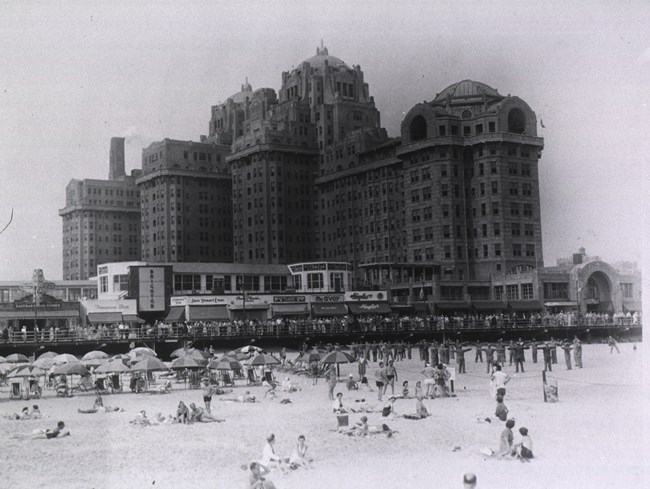

1. Thomas M. England General Hospital: Atlantic City, NJ

In 1941, the Chalfonte-Haddon Hall and Traymore Hotels became a US Army Air Corps (USAAC) Hospital. Built in the late 19th century, these hotels were city landmarks that helped Atlantic City become a popular tourist destination. They were just 2 of 47 former hotels that made up part of “Camp Boardwalk”, a hub of military activity in Atlantic City. In 1943, the USAAC hospital was upgraded to the status of General Hospital, and it was renamed Thomas M. England General Hospital. Lieutenant Colonel England is best known for volunteering for yellow fever research in Cuba in 1900.

Thomas M. England General Hospital received its first patients on August 15, 1943. With a bed capacity of 3,650, England General specialized in neurology, amputation, and neurosurgery. The hospital’s prime location on the boardwalk accommodated soldiers of different abilities. Patients who had recently undergone amputations or other procedures could easily travel on the boardwalk. Soldiers were encouraged to do activities on the beach including surfing, pitching horseshoes, and playing volleyball and football to keep themselves in shape. During the war, England General was the largest hospital in the world, treating 61,000 patients between 1943 and 1946. In 1946, the Army canceled its lease and the hotel returned to its owners.

Atlantic City’s tourism industry suffered in the 1950s and 1960s until gambling became legal in 1976. Due to this economic downturn, many hotels fell into disrepair and were demolished, including the Traymore Hotel in 1972. The Chalfonte Hotel was not big enough to become a legal gambling establishment, and it was demolished in 1980 after being surveyed by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS). Only the Haddon Hall hotel still stands today, and is known as the Resorts Casino.

Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

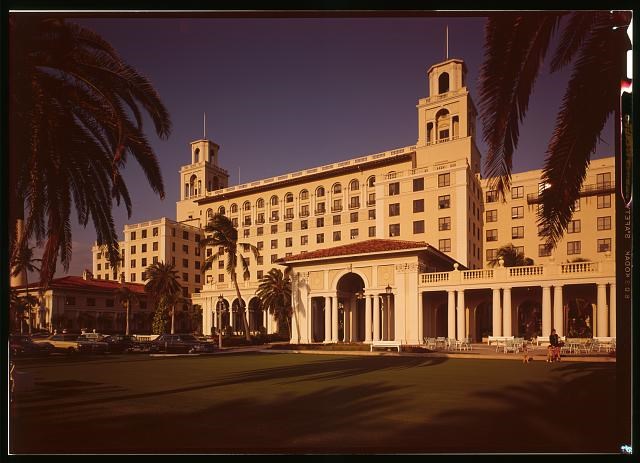

2. Ream General Hospital: Palm Beach, FL

The Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, Florida, also boasts a service record in World War II. Built in 1926, this luxury resort first housed an Army Air Corps Hospital. In 1943, it became Ream General Hospital. It is named after William Joy Ream, a Major in the Medical Corps who was considered the first “flying surgeon” in the US Army.

Ream General Hospital received its first patients on September 10, 1943. The hospital’s specialty was neuro-psychiatry, orthopedic, and plastic surgery, and it had a bed capacity of 500. The nearby Breakers Cottages were also used as barracks by the officers and nurses stationed at the hospital. More than a dozen servicemembers’ babies were also born at Ream between 1942 and 1944. These babies were known as “Breakers Babies.”

Local Floridians volunteered their time at Ream during the war to ensure the comfort and speedy recovery of patients. Performers entertained the patients, providing much-needed morale boosters. The hospital also hosted First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and then-Missouri senator Harry S Truman in 1944. They toured the facility and chatted with patients. In 1944, the Army returned the hospital to its owners. The hotel reopened later that year to civilian guests. This move was widely criticized by locals, as they felt treating service members was more important than reopening a hotel for civilians.

The resort still stands today under the same name. The Breakers was surveyed by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) in 1971, and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 14, 1973.

Public domain. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

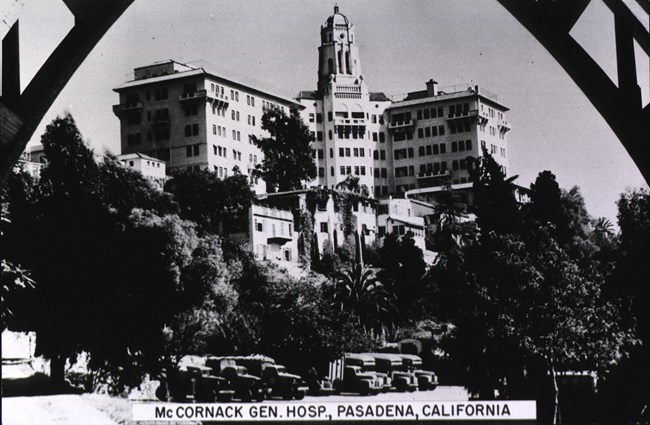

3. McCornack General Hospital: Pasadena, CA

The Vista del Arroyo first began as a boarding house in 1882, and was one of the oldest structures in surrounding Pasadena. In 1919, the building underwent extensive additions, turning the small hotel into the large Spanish Colonial Revival structure seen today. The Army acquired the hotel in 1942 and it opened shortly after as a regional hospital. In 1946, it became McCornack General Hospital. The hospital was named for Brigadier General Condon C. McCornack, the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Western Defense Command.

McCornack General Hospital had a bed capacity of 742. It received patients from smaller station hospitals that shut down at the end of the war. To boost morale and provide entertainment, hospital volunteers asked celebrities to visit the service members. Celebrities who answered the call included Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth. In 1949, the Army decided to close the hospital. Given its location within a Pasadena neighborhood, it was unable to expand, making it unsuitable to continue as a general hospital.

Today, this building houses the Richard H. Chambers United States Court of Appeals. The Vista del Arroyo hotel building was surveyed by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 2, 1981.

Public domain. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

4. Ashford General Hospital: White Sulphur Springs, WV

One of the most distinguished resorts in the eastern United States served in multiple ways during World War II. The Greenbrier Resort, first established in 1800, began as an internment center for German, Japanese, and Italian diplomats. In 1942, it became Ashford General Hospital, named after Colonel Bailey K. Ashford. Colonel Ashford is known for his research on anemia and for founding the School of Tropical Medicine in Puerto Rico.[2]

Ashford General received its first patients on November 14, 1942. It specialized in neurology, vascular surgery, and neurosurgery. The hospital had a 2,025-bed capacity. Patients had access to a wide variety of amenities on the ground, including a pool, golf course, tennis courts, and the hot springs. During its four year tenure, Ashford treated 24,148 patients. These included notable patients General Omar Bradley and General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Ashford General closed in June 1946, and the entire resort was repurchased by its former owners, the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway.

Today, the resort is still a top destination for vacationers. The Greenbrier Resort complex was surveyed by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) in 1983. The Greenbrier was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 9, 1974. It became a National Historic Landmark on June 21, 1990. The Greenbrier is also a part of the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area, which was designated in 2019.

Public domain. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

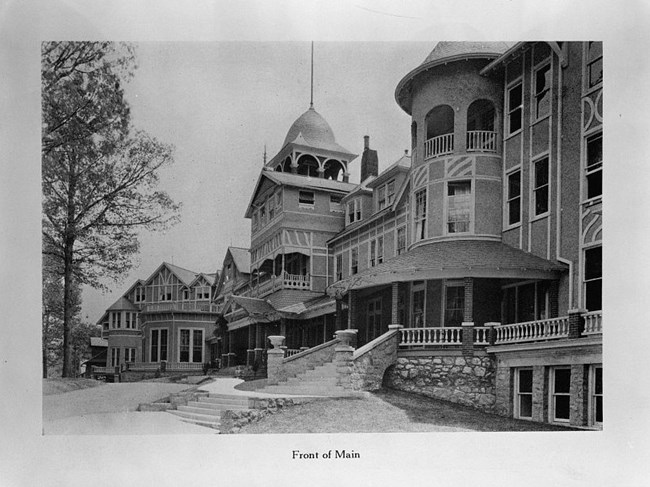

5. Walter Reed General Hospital Annex: Forest Glen Park, MD

In 1943, the National Park Seminary building joined the war effort. Opening in 1887 as the Ye Forest Inne, this Queen Anne-style building served as a resort for Washingtonians to escape the hot, crowded city. However, the Inne did not prove to be financially successful. In 1894, it became National Park Seminary, a finishing school. The facility remained a school until the Army condemned it in 1942 to turn into the Walter Reed General Hospital Annex. Its namesake, Major Walter Reed, was best known for his yellow fever research in Cuba.

Walter Reed Annex received its first patients on January 20, 1943. Designed to relieve crowding from the nearby Walter Glen General Hospital, the Annex specialized in rehabilitation for amputees and psychiatric patients. These soldiers were not ready to return to active duty, but they also were unable to be discharged from service. Patients had access to the facility’s pool tables, shuffleboard courts, and ping pong tables in the Annex's idyllic forest setting. These provided an opportunity for recreation, but also a chance for patients to adjust to life without their missing limb. Several patients later reported that they misrepresented their rehabilitation progress to stay at the Annex longer!

After the war, the Annex remained a medical facility for the Army. Today, the buildings are residential properties, retaining their historic integrity. The entire property was surveyed by the Historic American Building Survey (HABS) in 1999. The National Park Seminary Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 14, 1972.

The content for this article was researched and written by Hannah Haack, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education and the Park History Program.

Notes

[1] For more examples, check out these articles: Morale, Welfare and Recreation in WWII National Parks and Yosemite's World War II Hospital.

[2] The School of Tropical Medicine was listed in the National Register of Historic Places and designated as a Puerto Rico Landmark in 1983.

Bibliography

Atlantic City Free Public Library. “Camp Boardwalk.” Accessed June 30, 2022. http://www.acfpl.org/component/content/article?id=226:camp-boardwalk.

The Breakers. “Historical Timeline.” About The Breakers. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.thebreakers.com/about-breakers/look-back/.

Brooks, Michael and John Burns. “Chalfonte Hotel.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1980. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. NJ-869). Accessed July 1, 2022. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/nj/nj0800/nj0889/data/nj0889data.pdf.

Cloutier, M. M. “When The Breakers was a hospital.” Palm Beach Daily News. Published February 2, 2019. Accessed June 30, 2022. https://www.palmbeachdailynews.com/story/news/history/2019/02/02/memory-lane-breakers-repurposed-as-hospital-during-wwii-visited-by-eleanor-roosevelt/6131836007/.

Conte, Robert S. "The Greenbrier." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Charleston: West Virginia Humanities Council, 2013. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/42.

Corbett, Michael and Robin Sweet. “Vista del Arroyo Hotel & Bungalows.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1980). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/123859603.

Crisson, Richard C., Richard High, and Woodrow Wilkins. “The Breakers Hotel.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1971. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. FLA-288). Accessed June 30, 2022. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/fl/fl0100/fl0174/data/fl0174data.pdf.

The Eugene Guard. “Condon C. McCornack Obituary.” November 6, 1944. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/28774128/condon-c-mccornack-bg-mc-usa-obit-2-2/. Accessed June 30, 2022.

Grunke, Roger H. “The Breakers Hotel Complex.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1971). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/77843559.

Harding, James E. and C.E. Turley. “The Greenbrier.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1974). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/86535069.

Keefer, Louis E. "Ashford General Hospital." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Charleston: West Virginia Humanities Council, 2019. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/304.

Meares, Hadley. “SoCal Drafted Its Buildings To Help Win WWII — And We're Doing It Again To Fight Coronavirus.” LAist. April 13, 2020. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://laist.com/news/la-history/how-socal-repurposed-buildings-wwii-coronavirus-wounded-soldiers.

Miller, Nancy. “National Park Seminary Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1972). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/106777846.

Ott, Cynthia. “National Park Seminary.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1999. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MD-1109). Accessed July 12, 2022. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/md/md1500/md1503/data/md1503data.pdf.

Smith, C. M. K. The Medical Department: Hospitalization and Evacuation, Zone of Interior. United States Army in World War II: The Technical Services. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989. https://history.army.mil/html/books/010/10-7/CMH_Pub_10-7.pdf.

“Vista Del Arroyo Hotel Complex.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. CA-2184). Accessed June 30, 2022. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ca/ca1200/ca1269/data/ca1269data.pdf.

Waltzer, Jim. “War at the Shore.” Atlantic City Weekly. December 15, 2005. Accessed June 29, 2022.https://atlanticcityweekly.com/news_and_views/war-at-the-shore/article_ed01f74e-14ef-5562-aab6-f6fa8cd5c0e3.html.