Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Cultural Landscapes: Places That We Look at Every Day, But Often Don’t Really See

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

Robert Melnick

Robert Melnick: I want to thank a number of people you've already heard from but who are the sponsors and obviously Preservation Texas, Evan and Jane especially, but the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training that I've been working with and known about, since about 1994, I guess, Debbie. The National Parks Conservation Association, of course, and the National Park Service in the form of Julie from Guadalupe Mountains.

Some of the speakers here today I know and some of them I know very well, but others I don't know. And I'm especially interested in hearing what they have to say, and to learning from them. I think one of the secrets to working with cultural landscapes, as Julie said, is to constantly be learning, to constantly be asking questions.

It would be an understatement to say that I'm truly honored to be here today to introduce this symposium and to share some ideas with you and to listen and to learn from each of you. We've already had some good conversations yesterday and that's going to continue.

Cultural landscapes to me are like people, they may look similar but when you scratch the surface, you find they each have defining characteristics and their own personality. Dig even deeper, and they can be very different from each other, yet similar in often remarkable ways. And that's part of the challenge of working with cultural landscapes.

So if you bear with me, and I'd like to start with a landscape story and frankly, it's a very personal story. I can't quite remember the very first time that I realized that landscape was important to me. I suppose I was quite young, maybe even eight or ten. Although I grew up in New York, right here, I spent each summer of my pre-adult life outside of the city in a rural area of small summer cottages up and down a long and winding gravel road, dotted with rundown houses, dairy farms, pig farms, apple orchards and surrounded by hills and trees.

As a city boy, and I really was a city boy, I underwent a dramatic transformation each summer. As I left my friends and streets and hard edge playgrounds the day after school ended in June and discovered and rediscovered the woods and stone walls and worn paths through the forest that I could traverse at night without a flashlight.

It was in many ways, I now know a wonderfully rich climax and mature forest with oaks and maples and ferns, but also with bugs and worms and too many birds for me to ever name as well as fox and deer. We were told to the occasional bear but I always thought that was probably a lie. Although I can't, and I was always told it was the country which is what you called it.

It was more importantly, a landscape rich in Native American history, with a non-native population settlements dated to the earliest days of the Dutch and English on this continent. There were place names from the earliest non-native settlements, but also place names tied to the landscape form and process. Putnam County and I don't know where I found this map from but, you know, I told some friends I was actually… I'm going to spend the rest of the week in Texas, I was using a paper map and they were amazed.

Putnam County itself is named for a general of the Revolutionary War, but they're also place names like Peak Skull Hollow Road with a reference to both the Dutch and the landscape. Piano Mountain named for the shape of its ridge line against the sky, Brian Pond Road, Rory Ruck Road, Four Partners Road and so on.

There were not terribly unusual names in fact, yet they fascinated me with their reference to both place and past. There are no doubt similar distinctive place names where you live, and in places that you inhabit and that you grew up in. It was only later in our history when towns were platted as speculative property that we acquire the ubiquitous Elm and Maple streets and even then, there are precedents tied to street tree plantings.

For me, then and now, this landscape was a remarkable and joyous place. There were sounds I only heard in the summer, like the incessant hum of crickets until dawn. There were smells and sights, like a summer rain that was not steamy or the flowers of honeysuckle, lilac, day lilies, and the Rose of Sharon that my mother grew outside our house. It was a domesticated family landscape, made comfortable at a 1950s mode in the midst of a rural now suburban landscape that had at one time been wilderness, but it was no longer wilderness.

Even though the contrasts with the wilds of the city, because they really were wilds in the city, could not have appeared to be greater to me. And they were wonders that awaited me even though they were sometimes unpleasant. I remember falling and getting cut and all that kind of stuff that happens. But I was not alone in this landscape. There were friends I treasured to this day, and these are those people I could name them for you still who I'm still very close with. All children of the post war boom, who like so many others sought a place beyond the city and found another home in this rural landscape. They are friends linked forever to this landscape.

Our small cottage was near a lake, really a pond. There I discovered other natural wonders like leeches and snapping turtles, some of which rumored to be 100 years old, but who knew if that was true or not. Here also, I learned to use a rowboat and a canoe and quietly explore the edges of this pond with its grasses and lily pads.

I understood that for some reason there were warm and cold spots of water when I swam. I learned to leave the ponds edge at dusk or risk being eaten alive by the black flies. There were red winged blackbirds that hovered near the water and there were also butterflies. The cool air coming off the pond made us so glad that we were away from the unforgiving, unrelenting intensity of a hot New York City summer.

In New York, I also learned the landscape, but it was of a different kind. There was Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx where I could ice skate every winter with friends. There was Inwood Park at the northern tip of Manhattan, with a notorious purchase of that island supposedly occurred and where I could play on rock outcroppings.

There was smaller green patches of neighborhood landscape, and there was always Central Park. I was warned regularly to be extra careful in Central Park, to never go there at night, or even during the day, to stay on the edges, to always be able to see the street.

It was this edge between wilderness and civilization that marked where I was safe and where I was not safe. There were always news stories and neighbors whispers about Central Park. And we all knew that the park was a place gone bad. It was only later as a graduate student returning to visit with fresh eyes, that I fully discovered the joys, intricacies and delight of the Olmsted and Vaux park design.

What was it then that made these landscapes so special and so magical in my life and in your lives? What still makes them important today? What do we value about landscapes that makes us want to ensure their life for the future and for future generations? That makes us want to know that years or even decades from now, others will come to treasure them as much as we do, although perhaps in different ways. What is it about cultural landscapes that makes them so intriguing, yet sometimes so difficult to understand, to document, and especially difficult to protect?

Robert Melnick

I think about cultural landscapes the way I think about people, as I said, because they are living entities with histories, yet they change over time, and are usually recognizable from one period of their life to the next. This to me is one of the wonders of cultural landscapes. I like to say that cultural landscapes are both nouns and verbs. They are objects, but they are also processes. They can emit a sense of stability, yet they're also dynamic.

And like the title of this talk, we often look at them every day, we pass them by, we live in them, but often we don't really see them. We don't really see what makes them special and worth treasuring. What is it in the landscape that makes them worthy of our special effort to protect and preserve them? You'll see all of this on, you'll see Bassett Farms on Wednesdays you know.

Like many scholars of my time, I came to work on cultural landscapes in a roundabout way. There were no courses, and few teachers. There was certainly no method or way to do this work. We were feeling our way like here, as Julie said at Buffalo River in the dark, sometimes tripping over ourselves more often discovering. Cultural landscapes really are treasures, as they come from the explicit or implicit decisions that people make every single day, sometimes in big ways, and sometimes in small ways.

Sometimes they are designed landscapes like this at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, and they can be historic parks, roadways or trails. And sometimes they develop as people make individual operative decisions each day, each season or each year, like ranches, farms or mining landscapes or this Taro landscape on the north shore of Kauai in Hawaii.

Robert Melnick

I've been working in cultural landscapes for the majority of my professional career, and to be honest, I'm still learning. People sometimes ask me if I have a favorite cultural landscape. Of course, I have ones that I especially like and Hanalei that you're looking at now it's really one of my favorites, places that I returned to again and again. But if you asked me today, my favorite landscape tends to be the last one that I saw, the one that I saw yesterday, the last cultural landscape that enticed me to understand it better, or that has a personality trait that I have never seen before. My wife says it's amazing. We're still married after 40 years. I won't go into that.

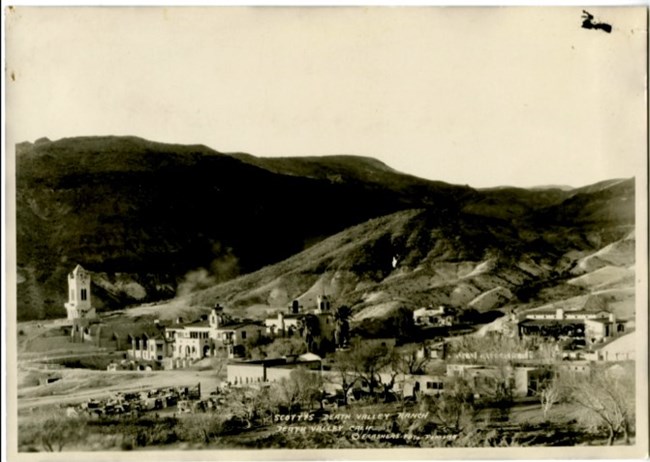

And maybe Scotty's Castle in Death Valley National Park. The Columbia River Gorge that joins Washington and Oregon, Boxley Valley of Buffalo River, a technical research site in Los Alamos National Laboratory that we're currently working on with Julie, Hanalei Valley on Kauai, Mountain Taishan in China, a fish hatchery in the Redwoods National Park in California, an earthquake fault line in the Marquee Region of Italy, Fort Jefferson in Dry Tortugas National Park or Bassett Farms, somewhere. There we go, okay. Bassett Farms, a fascinating, and remarkable landscape as you already heard from Evan and that we're going to spend a lot of time on, on Wednesday.

Visiting these landscapes, learning about them and helping to chart the course of their future is always exciting, yet always a challenge. As my friends, colleagues, students, family, especially my children, will tell you, I love visiting, seeing and exploring landscapes, but I especially love talking about them and learning about them. I get excited when I see new landscapes as well as those I know well. I get excited because there's always something to discover, and I never fail to marvel at the sometimes subtle or blunt ways in which these places speak to us.

These are truly special places, landscapes that tell us so much about where we have been as a people, where we are today, and perhaps even where we are going. I like to say that cultural landscapes help me and I think help all of us understand where we are in time and space.

But cultural landscapes can be difficult to understand, challenging to document, analyze, evaluate, and even more difficult to protect. So, if I can, let's get down to some work. Here are some basis to consider. Cultural landscapes are the results of natural systems and human systems interacting and coming together. We can't understand Bassett Farm, for example, without knowing about the soils, the native vegetation and the prevailing climate patterns. But we also can't understand those natural systems without knowing what the farmers and residents did to this landscape, how they plowed the fields, built the houses and the barns, raised cattle, played in front yards, or managed economic ups and downs.

Cultural landscapes are where natural and cultural resources intersect. For some of our current projects at Pecos National Park and Fort Union National Monument, both in New Mexico. We're working very closely with ecologists as we seek to listen and to learn from each other, and that really means speaking two different languages.

It's two different language as much as you might speak to someone who you're speaking French and they're speaking Mandarin. It's really sometimes challenging, but it's exciting. We see the same landscape but often through a different lens and we ask different questions. And it's those questions that are very important.

Robert Melnick

Cultural landscapes are complex systems that are best understood at multiple scales. So what do I mean by that? Let me go back to people for a minute. We can understand people in many ways. There are national groups, religious groups, regional groups. There are individuals, and those individuals each have a personality and physical traits: height, hair color, weight, eye color, shoe size, skills and abilities and the list goes on and on. Cultural landscapes also could be seen at multiple scales. Are they agricultural landscapes or ranching landscapes or mining landscapes? Are they urban parks or large residential neighborhoods? Maybe there are military battlefields or significant historic sites that tell stories of the past, like the remnants of the Santa Fe Trail at Fort Union that I just showed you.

Often cultural landscapes can be understood through many different lenses, just as you see people in different ways. In order to engage a cultural landscape, we need to get beyond our feelings to ask the many questions that could be answered in organized and often technical ways.

The intention here is to understand the cultural landscape palette. What are the places that when joined together make the landscape what it is? What defines it? This requires knowledge about the landscape’s past, recording, and documenting its present condition and also envisioning its future.

In that way, we can know where the landscape has been, where it is now and where it might be going. And I'm not suggesting landscape prediction because I really don't think that's what we do. But I am including landscape projection, where it might be going, especially when it comes to preservation and management. I want to share with you how we generally do this work, as Julie mentioned, what the goals are and some final products. But I want to begin with those questions and go from there. I think you'll see right away that one key to understanding cultural landscapes is asking questions and asking them often, again and again and again.

Robert Melnick

We have questions about a cultural landscape that we asked there on the table until the project is done. It's a very cyclical process not linear at all. We begin by asking, why is this landscape important as this landscape in Rush, Arkansas? In preservation terms, why is it significant? And what is the landscapes historic context? Just as we analyze and understand the landscapes geographic surroundings, we also need to know its historical surroundings. Was it developed during the Civil War era or in the period of cattle ranching after the wide use of barbed wire was implemented? Does it predate incursions by non-native settlers? Perhaps it was made during the challenging days of World War II. We can't understand and know a cultural landscape without learning about its multiple contexts.

It's important to remind ourselves that not all cultural landscapes are significant. This is a park in Caracas, Venezuela. Cultural geographers help us understand that in one real sense, the entire globe is composed of cultural landscapes. Given our technologies and human presence, there are no places on this earth that are not touched in both large and small ways by human activities, especially in this era of climate change that we hear about later today. I should say that I am an absolute non believer in the continued existence of wilderness. I just don't think it exists anymore because of what we've done to the globe.

How can we determine then, why and how a cultural landscape deserves to be documented, understood and preserved? It's the same question we ask about historic buildings, sites or neighborhoods. What role does this landscape play in local, regional or national history? Is it associated with an important trend, style or period or all three? This should be recognizable to most of you.

Once we have established a cultural landscapes context and history, or perhaps while we're doing all those steps, we really need to get to know the landscape better. So how do we do that? Over the past 40 years, the National Park Service has developed what is now an established framework method for looking at cultural landscapes, documenting them, assessing integrity and planning for their future protection. And I underline the word framework here. This is not a recipe it is a framework for approaching this work.

In very broad terms, there are three parts to this process, research, planning and stewardship. As I said, not all cultural landscapes are the same, but the approach to their protection is founded on these fundamental steps. It sounds basic and easy, but it can often be challenging. The first step is research. What do we know about a landscapes history, its physical development and its current condition? This is fundamental. And as with historic structures, we get past visual appearance down to the real nitty gritty.

I want to say also that while this effort appears to be sequential, as I said, it really doesn't work that way. We often start by having an interest in the landscape, wondering why it is the way it is, someone may bring it to us, or we may notice it ourselves as you heard yesterday, and as in the bootcamp and as you're going to hear today.

Other engaged parties may often know something that the research team doesn't know. Maybe it's a scrap of history or a historic photo, a letter, a diary, maps, news clippings or a local story passed on from one generation to the next. In this way, I'd like to say that we're all landscape detectives seeking to find the truth about a landscape to the extent that we can, but that bit of history sparks the imagination, and the need to dig, and dig, and dig, and in order to get it right, and being a landscape detective really means you look for clues and you go from there.

As in any good historical research, we employ primary and secondary sources, letters, photographs, maps, recollections, oral histories, previous studies, and on and on and on. As a landscape research team will tell you this work is directed and methodological but we also follow our instincts. I did some work a number of years ago at Sutro Baths in San Francisco. And in the process, which was an early, early public baths in the 1890s and turn of the 20th century. And in looking, doing the research there, we came upon some men's bathing suits in libraries, those full one piece bathing suits that we never thought we were looking for. So it's just kind of following your nose quite literally.

Additionally, we need to document and analyze the landscape as it is today. And as it was during the period of significance. So how do we do that? Because that really forms the essence in many ways in the core of what we're doing. The cultural landscape process or method is really driven by 13 characteristics or categories that have been developed and refined and changed over the past 40 years. This is not really new anymore. But it's important to think of these as categories. And I'll explain that why in a second.

This is very purposely broad and very conceptual. The goal here in the documentation phase is to include every element or every feature in the landscape. As I said, it's not a recipe. It's a comprehensive field research tool that ensure we don't miss anything. Years ago when I started this work we were looking at a National Register nomination for Grant-Kohrs Ranch in Wyoming, which was probably 30,000 acres, and there was a 50 page document describing the ranch house. This is absolutely the truth, describing the ranch house, every size nail, how many nails, the thickness of the boards, the layers of paint. And then at the very end, it said, “Surrounded by 30,000 acres of bucolic landscape, period.” And that left us all to think, “Well, something's wrong here, we need to do a better job.”

We looked for characteristics, and then we looked for features that reveal those characteristics. Sometimes we see and document the features and then assign them to a characteristic. If you're looking at a trail, you're not going to say I'm looking at the circulation system, you're going to say, this is a remnant of the Santa Fe Trail and it fits into the category of circulation. So that's why I said it's a very cyclical process. Remember that the landscape is not an object, it's a reflection of human use, human decisions and human activities in that ecological context. I can't emphasize that enough.

We looked at the landscape processes, what did people do there? And we look for results and outcomes of these processes. What did people construct or develop or adapt? While doing this field work, we also defined the boundaries of the cultural landscape, and for the purpose of the research, planning and stewardship. Sometimes the boundary is very obvious and clear, other times it's much more difficult to determine. There are ecological boundaries, where does the cultural landscape fit in that larger context? There are historical boundaries, what was the development? What was developed or built or changed during the period of significance? And practically speaking, are there political boundaries, who owns this landscape? What entity or agency controls it? Is that the National Park Service? Is it buildings and structures? What is the history of this site as we look at it? We look at natural systems and features that have influenced the development and physical development of this landscape over time.

So, what are the major components at the larger landscape scale? And here they are, there's the natural systems and features. How is it divided or recognized, where are the buildings, the roads, the trails or planted vegetation? And how do these features relate to the defined topography? What is the spatial organization? How is all this separated out and leveled out in the landscape in this three dimensional organization of physical forms?

Okay, so the spatial organization, is this an agricultural landscape, or is it an urban park? Were there or are there wheat fields or cotton fields? Was it used as a fish hatchery or for housing? What was the landscapes purpose? And not really singular but purposes, plural often. This is the primary land use, the way that people have used landscape both historically and currently. What did people do on a regular basis to make this cultural landscape and make it work for them both make it and make it work? If they tilled the land, did they have special ways of doing that? Were there special ways to plant and build walls and fences or even align roads?

These are the cultural landscape traditions, practices and methods employed by people or peoples who occupied and developed that landscape during its period of significance. Do buildings, small scale features, or other elements form a distinct pattern in the landscape at a smaller scale than the overall spatial organization? Are these only buildings and structures, or do they include paths, ornamental plantings, fences and smaller features? These are the clusters and recognized groupings of features. And how do people get through this landscape? This is a slide of a swinging bridge in Boxely Valley, Buffalo River which is long gone.

Are their roads and paths? How did people move through it? Did they move on rivers and canals or on foot bridges like this? Is there an airport? Are there sidewalks? Are there larger avenues and smaller streets? How did people move through this landscape? By foot, horse or car? These are the patterns of circulation that comprise the spacers features and applied material finishes, which constitute systems of movement in the landscape. This is at Nan Madol in the South Pacific, and that even though you think you're looking at water, you're looking at canals that people moved around on.

What is the physical form or setting, whether at a large or small scale that defines or frames the cultural landscape? At a smaller scale the natural systems or features. How is the cultural landscape defined and influenced by land form and changes in the land form? Is it subtle and substantially flat with minor elevation changes, or perhaps a change that dramatically impacts drainage and water flow, or just strikingly dramatic?

Do we start all over? No, there we go. Okay. Is there a hill in the north side or the south or no hills at all? We look at topography, we look at the basic land form at that detailed level. What did people plant here? Was it for look, ornamental, or for livelihood, economic, or both? Did it change over time? Is it still here and recognizable? What else does the vegetation tell us about this landscape?

Vegetation includes deciduous and evergreen trees, shrubs, vines, ground covers, herbaceous plants, plant communities, all planted and modified by people. We're about to start a cultural landscape report in Susan Dolan's favorite landscape I'm told at Buckner homestead in the North Cascades, which is one of the first orchards in the apple industry in the state of Washington. And it's a really remarkable place. What did people build and importantly why? What are different building types and what are the structures? Buildings and features constructed for sheltering any form of human activity. Structures are features constructed for purposes other than sheltering human activity, and may include mechanical and structural engineering systems.

These are what is most easily seen when looking out on the landscape from this perspective, they are a feature of the cultural landscape. What do we see when we look at, in or through this landscape? What was seen within it from the outside and to the outside? Why are these views important? And what did they reveal about the structure and development of the landscape and the activity… Sorry, that's the buildings and structures. There we go. Activity that took place within it? How important was it to see from one location to another? Was it for function, landscape comprehension or often for security?

Views are the direct lines of sights, and view sheds are the wider, broader scans across the landscape. I think of a view like a stream, and I think of a view shed like a watershed, if you didn't know the ecological understandings. How did water move through the landscape, and what purpose did this serve? Were there acequias, canals, ponds, wells, water channels or diversions?

Constructed water features are the built features and elements that control, manipulate and focus water for aesthetic or utilitarian functions in the landscape such as this acequias in Choroni, Venezuela on the ocean coast. Are there a singular fence posts or clotheslines, one of my favorites, or pump panels or benches? And what did they tell us about this landscape? How it was made, developed and most importantly, used.

This clothesline is at a site in Pearl Harbor. And it was there in December 7th of 1941. We're doing the cultural landscape for the site in the middle of Pearl Harbor. And it was very clear that you could envision people hanging up clothing, hanging up laundry here on the morning of that attack, and before and after. So the clothesline believe it or not, this post, this clothesline post became an important element to help us tell the story of what this residential site was like at Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Small scale features therefore, are the elements which provide detail and diversity for both functional needs and aesthetic concerns in the landscape. What and where are the ruins, traces or deposit artifacts in the landscape? That evidence, the evidence, the presence of either surface or subsurface features, with the active participation of knowledgeable archeologists on our team. What do these sites reveal about past landscape occupants and users? What can we learn about the different cultures they inhabit? Some still extant and some long gone and the ways in which they habited these places.

Were there dwellings, trails, handholds, or footholds? Were dwellings above ground or below, and these, of course, are the archeological sites. The goal of this field reconnaissance and documentation is to make sure that we understand the entire landscape that nothing is left out. That's why we explore the landscape at multiple scales, with multiple characteristics or categories, with multiple team players and with a variety of features.

Robert Melnick

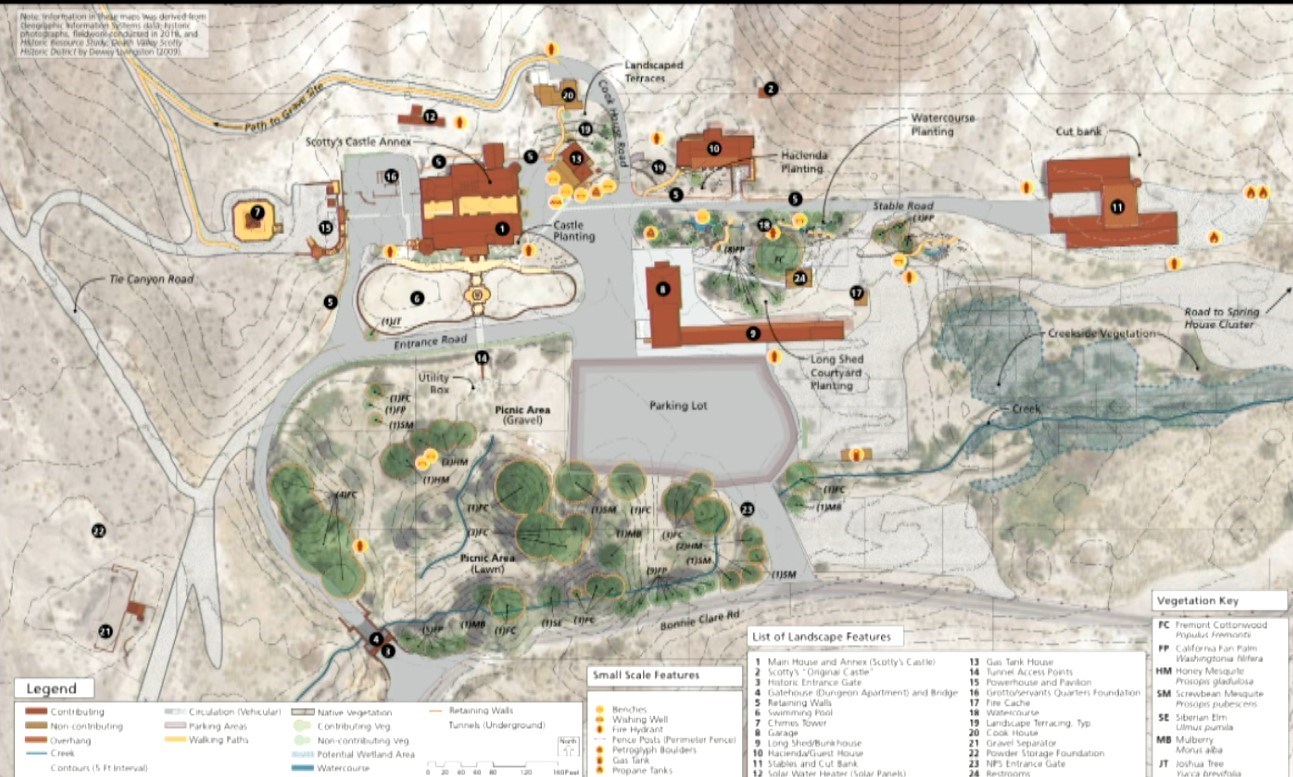

The end result of this phase of the work is a comprehensive view, that may take a second to load. There we go. This is the fish hatchery in Redwood National Park. And it's a comprehensive view and understanding of the place and its largest natural setting and feature to its smallest element.

To fully understand the cultural landscape changes over time, we then develop period plans. What was the landscape like at its important point in its history especially the end of its period of significance that the historians tell us about? How did it change when important features were added or taken away? And what does this cultural landscape tell us about its past, about the people who lived or work here and what they did?

Often, this is among the most difficult challenges of this work. We want to know about the landscape now, but we also want to know about the landscape then, as in these two slides from Rapidan Camp in Shenandoah National Park. This can also help us to explain not only what happened but why it happened? Was there a flood that resulted in a new or what's now a historic bridge? Were there economic successes or failures that altered the direction and substance of the landscape? Did people come and go? Were there technological changes that made earlier methods or techniques obsolete?

We are continually being detectives, with the goal of piecing together a landscapes history, when all we have left are but remnants of memory and recollection, whether written, photographic, oral or documented in some other way. I expect and if you're not, you should be asking, so what do we do with all of this stuff, right? Why do we do this and what happens next?

First, we look at all of this together. And this is where this moves into an analytical and often very creative mode. We ask, what about this landscape? And this is at Scotty's Castle in Death Valley. We ask what about this landscape makes it what it is? Is it the way the major features are organized as in the significant landscape at Los Alamos National Laboratory, or the groups of features otherwise known as clusters, as I said earlier, that reveal much about the human activity? Maybe it's the way people moved to and through this landscape, as on the Santa Fe Trail that I showed you a few minutes ago in New Mexico, or the way they planted and harvested crops, as in the Taro ponds in Hanalei Valley on Kauai.

Robert Melnick

Is it the natural hydrological system, or the topography, or the cell structure as we discovered at Hanalei? And the answer here was the cell structure. This was clay, they tried to plant coffee trees here as it did on the Kona coast, and they all died until we very quickly through, actually a colleague of mine figured out that because it was clay, you didn't get any good drainage and therefore all those trees were drowned. So it was actually a fairly easy answer once we knew what we were looking for. Or the way water was brought from one elevation to another and distributed across an agricultural landscape as in the cacao haciendas on the Choroni region of Venezuela that I showed you a few minutes ago.

If we want to protect, honor and preserve this landscape, in all cases, we asked, what are the character defining features? Those extant features then become the most important to protect, but often not the only ones. What does this landscape feel like? And has that changed since the period of significance or as in this added paving on a historic Fish Hatchery at Redwood National Park? The paving you're looking at is not original, it is not historic, and it has dramatically changed the feel of this place. Our recommendation is going to be to remove this and do some other treatment.

So, now's a good time in this process to go back to all those characteristics and features and ask the same questions. What is most important, what contributes to the character of the landscape? Sometimes it's the big features in the largest scale. Sometimes it's the grouping or clusters or the circulation system or the collection of smaller features. Most often however, it is the way in which these features work together as a system, how they intersect. This is not the time to treat the landscape as a series or as a set of features or objects. It is the time to understand how they work together as a system, and that is a critical concept in this work.

I want to add another thought here and one which some of you may be wondering about. Is this spaced, as in many National Register work much work on counting features, or getting a feel for what they are? Is this about quantitative or qualitative data? Is it about hard numerical facts or about creative analysis of what we see and know? And the answer is yes, it's about both of them. It's about both counting, and it's also about analyzing the feeling and understanding of what you're looking at. It is not about quantity or quality, it is really about quantity and quality.

Robert Melnick

While we may count the cultural landscape features and measure them and assess their condition, which we do, the work is also about understanding the meaning of these places and the qualities of these places. At the fish hatchery in Redwood, we were given an archive filled with these photographs of people enjoying this place. And it was really clear this is much more about the fish. It was really about, it was also and greatly about the people.

It is not enough to have a spreadsheet of features and photographs, although it's necessary and where they are on a detailed map obviously, we need to know that, but studying, evaluating and protecting a cultural landscape goes beyond those technical details.

I want to go back to where I started as I wrap this up. Cultural landscapes, and that I mean significant and meaningful cultural landscapes, to remind you of that, can be places that we look at every day, places that we often live in, or walk through, or work in, or just notice as we go past them. But far too often these are places of our lives and the lives of our communities that we really don't see, we don't understand and unfortunately, we really don't engage to the extent we should.

Robert Melnick

And yet in cities, in small towns, in the Texas countryside, in the wonders of the Cascade Mountains, or the depths of Death Valley National Park, they are often the glue that holds communities together. They are places with buildings and benches, open spaces and visible horizons, ways to walk, ways to harvest and the surrounding topography and watersheds enable us to farm or to just survive.

Yet some cultural landscapes, of course have greater significance than others. Determining that is really part of our task and our challenge. For if everything and every piece is important then I would claim that nothing is really distinctive. If everything is important, then nothing is really distinctive.

You'll be treated in the next few days, to information and material on different types of cultural landscapes, excellent examples of their documentation and treatment, and especially the challenges that are being faced as we seek to protect them. This is exciting work. There we go. And I encourage you to think about cultural landscapes that you know, cultural landscapes that can be better understood, documented and protected now and into the future.

I want to close with one more brief story that I really want to share with you. Years ago, I was tackling a project nestled in the Sawtooth mountains of Montana. And I was still learning how to understand cultural landscapes or even how to talk to people. I was interviewing a cattle rancher who had grown up and lived all of his life in this powerful and dramatic landscape. I didn't know what to expect. I was asking careful questions in the hope that he would open up to me and share some insights into his ranching techniques. I was looking for that quantitative data, how he uses land and the tools.

Robert Z. Melnick

Speaker Bio

Professor Emeritus Robert Z. Melnick is a nationally and internationally recognized expert in cultural landscape evaluation and historic landscape preservation planning. A Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects, Robert has published widely on theoretical and practical issues relating to cultural and historic landscapes. He has served as lead and consultant for projects in states across the country, including Hawaii, California, Oregon, Iowa, Texas, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. His written works and professional projects have received numerous national awards. Robert regularly lectures at universities and professional meetings. He is Director of the UO Cultural Landscape Research Group (CLRG).

Robert's most recent work on the impact of climate change on cultural landscapes in US national parks received a 2017 ASLA Honor Award in Research. Along with Graduate Fellows in CLRG, he is currently wokring on projects at Fort Union National Monument, Pecos National Historic Park, and the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, all in New Mexico.

Robert is former Dean of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts (now College of Design). While on leave from the University of Oregon (2005-2007) he was a Visiting Senior Program Officer at the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles. Robert is also a Senior Cultural Resources Specialist with MIG, Inc., a consulting firm in Berkeley and Portland. He does not teach regularly scheduled classes.