NPS/Corey Lycopolus Despite the healthy bear population across Valles Caldera and the Jemez Mountains, American black bear sightings are fairly uncommon, as they are solitary and somewhat elusive creatures. Black bears are omnivores, so they will eat almost anything. They compete with other large mammals for food and resources, but their opportunistic eating habits allow them to be highly adaptable, feeding on whatever is available. In the Jemez Mountains, black bears are known to drive mountain lions away from kill sites. This behavior contributes significant carrion to the food web, which is an important resource supporting ecosystem biodiversity and structure. PopulationBlack bears are most commonly observed in the park during the summer months, particularly elk calving season. Black bears have few natural predators, although both cubs and adults are occasionally killed by their own kind or by the other large carnivores with which they compete for food, such as mountain lions. Most black bear mortality in the park is likely attributed to old age or other natural causes. Outside the park, some black bears are killed during state regulated hunting seasons. Black bears are occasionally radio-collared for research focused on monitoring habitat selection in response to ecosystem changes and disturbance. Read more.

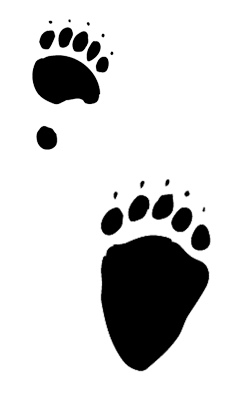

NPS DescriptionThe black bear (Ursus americanus) is the most common and widely distributed bear species in North America. Relatively few black bears at Valles Caldera are actually black in color; more often they are brown, blond, and cinnamon. Black bears eat almost anything, including grass, fruits, tree cambium, eggs, insects, fish, elk calves, and carrion. Their short, curved claws enable them to climb trees. Black bears spend most of their time during fall and early winter feeding during hyperphagia. In November, they locate or excavate a den on north-facing slopes between 5,800–8,600 feet (1,768–2,621 m), where they hibernate until late March. Males and females without cubs are solitary, except during the mating season, May to early July. They may mate with a number of individuals, but occasionally a pair stays together for the entire period. Both genders usually begin breeding at age four. Black bears experience delayed implantation. Total gestation time is 200 to 220 days, but only during the last half of this period does fetal development occur. Birth occurs in mid-January to early February; the female becomes semiconscious during delivery. Usually two cubs are born. At birth, the cubs are blind, toothless, and almost hairless. After delivery the mother continues to sleep for another two months while the cubs nurse and sleep.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

In this video, Ranger Hayley introduces the various behaviors and appearances of the American black bear, state mammal of New Mexico. ResearchSince 2013, the Large Mammal Monitoring Project has provided new insights on black bears, mountain lions, elk, and mule deer across the Jemez Mountains, demonstrating how these animals' populations and behaviors are impacted by changes in the ecosystem. Results have shown that 48% of bed sites for black bears are located in undisturbed habitat while only 11% and 2% of bed sites are located in thinned and prescribed burn sites, respectively. The continued monitoring and analysis of these data will help inform future decisions regarding forest management, wildfire mitigation, and habitat restoration at Valles Caldera National Preserve and beyond. Related ArticlesResources2015. Yellowstone Science 23:2. Yellowstone Center for Resources, Mammoth WY. Fortin, J.K., C.C. Schwartz, K.A. Gunther, J.E. Teisberg, M.A. Haroldson, M.A. Evans, and C.T. Robbins. 2013. Dietary adjustability of grizzly bears and American Black Bears in Yellowstone National Park. Journal of Wildlife Management 77(2): 270–281. Gunther, K.A. and T. Wyman. 2008. Human habituated bears: The next challenge in bear management in Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone Science 16(2): 35–41. Haroldson, M.A., and K.A. Gunther. 2013. Roadside bear viewing opportunities in Yellowstone National Park: characteristics, trends, and influence of whitebark pine. Ursus 24(1):27–41. Herrero, S. 1985. Bear attacks: Their causes and avoidance. New York: Nick Lyons Books. Meagher, M. 2008. Bears in transition, 1959–1970s. Yellowstone Science 16(2): 5–12. Richardson, Leslie, Tatjana Rosen, Kerry Gunther, and Chuck Schwartz. 2014. The economics of roadside bear viewing. Journal of Environmental Management. 140:102-110. Schullery, P. 1992. The bears of Yellowstone. Worland, Wyoming: High Plains Publishing Company. Teisberg, J. E., Haroldson, M. A., Schwartz, C. C., Gunther, K. A., Fortin, J. K. and Robbins, C. T. 2014. Contrasting past and current numbers of bears visiting Yellowstone cutthroat trout streams. Journal of Wildlife Management, 78: 369–378. White, P.J., R.A. Garrott, and G.E. Plumb, eds. 2013. Yellowstone’s Wildlife in Transition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. |

Last updated: March 5, 2024