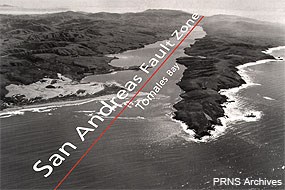

The Point Reyes Peninsula has long baffled geologists. Why should the rocks of this craggy coast match rocks in the Tehachapi Mountains more than 310 miles to the south? The answer lies in plate tectonics and the continual motion of the Earth's crust. Geologically, Point Reyes National Seashore is a park on the move. The eastern border of the park parallels the San Andreas Fault, which is the current tectonic plate boundary separating the Pacific Plate from the North American Plate. If you draw a line through the middle of Tomales Bay in the north through the Bolinas Lagoon on the south, this is the path of the San Andreas Fault Zone. Faults come in three types: divergent, convergent, and transform. The San Andreas Fault is an example of the third—a transform fault—where plates pass one another like cars on a two way street. Many visitors of our park are surprised to find that they are unable to look at a single crack, chasm, or other defining feature that is the actual fault. The San Andreas Fault Zone contains many large and small faults running parallel and at odd angles to one another which collectively have resulted in the Olema Valley, and the flooded sections of the valley form Tomales Bay to the north and Bolinas Lagoon to the south. The ridges parallel to the valley are called shutter ridges, a feature typically associated with transform fault zones.

NPS Photo Movement along the San Andreas Fault ranges from about 3.5–5 cm (1.4 to 2 inches) a year (about the speed your fingernails grow). However, instead of creeping along at a slow steady pace, the plates lock together for many years and build up tremendous amounts of stress. When the plates slip and release the stress, waves of energy are sent out and are experienced as an earthquake. The last time the plates here slipped by each other was during the great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. The greatest displacement in this area was about 7.5 meters (24.5 feet)! The earth's three rock types—igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary—are all found at Point Reyes. Our igneous rocks are granitic, which cooled beneath the surface of other rocks before erosion revealed them. These 80- to 100-million-year-old rocks originated in southern California, probably near Tehachapi. They are our basement rocks, and other rock types overlie them. In some places--like Kehoe Beach—the parent rock in which the granitic rocks formed are found. Altered by heat and pressure, these metamorphic rocks are the oldest rocks in the park. Our granitic rocks began moving before the San Andreas Fault formed and docked off of Point Lobos, where several distinct layers of rock formed above it. As a result, Point Reyes has six major sedimentary formations in it. The peninsula then started migrating north along the San Gregorio fault to merge alongside the San Andreas Fault along which it now travels. Point Reyes National Seashore is a park on the move, currently docked at Olema and Point Reyes Station, but destined to continue to move. Sea level rise also may bring changes to our park. At the end of the last ice age, rising sea level resulted in flooded valleys, creating Drakes and Limantour Esteros. What will the park look like in a century or two? Whatever the outcome, the rocks of Point Reyes will be here for your children's children to experience and appreciate. To learn more about the 1906 Earthquake, the San Andreas Fault and Plate Tectonics, check out our 1906 Earthquake Centennial Resource Newsletter (5,501 KB PDF) and the Point Reyes National Seashore Faults webpage. Or visit the U.S. Geological Survey's Earthquake Hazards Program web pages. U.S. Geological SurveyGeology of Point Reyes National Seashore California Division of Mines and GeologyGalloway, Alan J. 1977. Geology of the Point Reyes Peninsula, Marin County, California. California Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 202. Available at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/geology/publications/bul/cdmg-bul-202/index.htm. (accessed 15 November 2024). PDFs of the informational signs along the Earthquake Trail.

Adobe® Acrobat Reader® may be needed to view PDF documents |

Last updated: June 26, 2025