Hudson-Meng Bison Kill Site Earlist Signs of Humans The earliest signs of human presence along the Niobrara are found 150 miles upstream of the scenic river. The Hudson-Meng Bison Kill Site contains the disjointed bones of over 600 extinct Bison Antiquus, which makes it the largest known bison bonebed in the world. Archaeologists have also found a number of Alberta type spearpoints from a period 9000 to 9800 years ago at this site. These points are characteristic of the Alberta Culture of the Paleo-Indian period. It is unclear exactly what impact these early peoples had on creating this site, as it is unclear if they either killed these bison all at once by driving the herd off a cliff, or if these bison were killed near the same spot yar after year. Additionally, scientists suggest that it is even possible that these bison died because of a natural disaster, like a wildfire or flood. Regardless of what created this site, the presence of spearpoints indicates that bison have been integral to the lifestyles of the peoples who have lived in this area for thousands of years. During the Archaic period (2000 to 8000 years ago), American Indians used numerous sites in the Niobrara valley where they relied on a variety of small game and plant materials. The people of the Plains Woodland period (1000 to 2000 years ago) added the manufacture and use of pottery to their lifestyle. Through the Plains Village, Central Plains Tradition, and Coalescent Tradition periods (250 to 2500 years ago), these people began building semi-permanent earth lodges and supplementing their gathering with agriculture. Transcript

♫ [Music plays] ♫

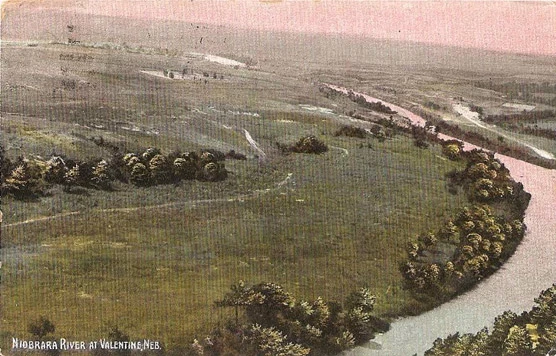

NARRATOR: The cool running water of the Niobrara has attracted people to its shores since ancient times. In the Ponca language, “Niobrara” means running waters or wide-flowing waters. Traditionally, when we traveled and we moved camp, there had to be a lake, or a spring or a river that we would’ve camped near. So we were always around the water. Holes like this— if you’re hungry, that’s where you catch your fish at. This river here, we used it for traveling to village sites, trading goods, and along the river there are places where we gathered different food sources. NARRATOR: Pawnee, Lakota, and other tribes also hunted and traveled through the Niobrara River valley. Europeans arrived in the 1700s, exploring and trading with American Indian tribes. The population grew in the area when the US Army established one of the last frontier forts to be built on the Great Plains in 1879: Fort Niobrara. The arrival of the Fremont, Elkhorn and Missouri Valley Railroad in 1883 opened the area to homesteading and cattle ranching. RICH EGELHOFF: My great-great-grandfather came over from Germany. And then my great-grandfather came to Keya Paha County just north of here. The house that they built, they built out of rock and cement. NARRATOR: Valentine City supplied the Sandhill region’s ranchers and homesteaders through sun and snow. When troops departed, Fort Niobrara was established as a national wildlife refuge in 1912. The red hay barn is all that remains from the early days. MAN: There you go! Rope him. Good Job! NARRATOR: Today, Valentine is still a cattle town at heart. The ranching heritage is celebrated on Main Street at the annual Bull Bash. ROD GIERAU: My grandfather come over from the Alsace-Lorraine and homesteaded right where we’re at in 1884. We’re one of the very first homesteaders in Keya Paha County. NARRATOR: The human history of the Niobrara River valley is rich and continues to link those who live along it today with those who have come in the past. DENNY BAMMERLIN: Once your land’s been in the family for 100 years, you feel pretty obligated not to mess up. There’s… it’s a strong connection to the land. I feel the presence of my ancestors when I'm close to the areas where they would have camped or where they would have lived. And when I'm in certain areas Where I know they were, where they lived, I get goosebumps, because I can feel them there.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Explore the recent human history of the Niobrara River Valley, which makes the Niobrara such a unique and wonderful place.

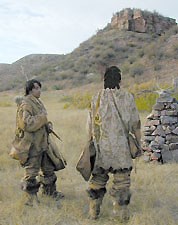

NPS photo by Linda Gordon Rokosz Local Plains Tribes Over the last several hundred years, numerous tribes lived in and passed through the Niobrara valley. Some tribes traveled through the Niobrara valley while following the bison, namely the nomadic Lakota and Pawnee. The Plains Comanche were also present at this time. While nomadic, these peoples were not necessarily wandering around the Plains; instead, they returned year after year to places like the Niobrara valley with the bison. The Ponca claim the Niobrara valley as their homeland. The Ponca built their earth lodges near the mouth of the Niobrara after separating from the Omaha in the early 1700s. Here they raised corn and launched hunting expeditions for big game. While there were prolonged conflicts between the Ponca and other tribes, like the Comanche and Lakota, they were motivated primarily by access to resources. As a result, warfare between tribes looked different than the warfare that westward expansion would bring in later years because it was rarely motivated by desire for conquest. During the 19th century, the United States government sought to define which tribes owned different lands so that settlers could move west into newly opened territory. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 divided the Sandhills and Niobrara valley between the Lakota and Pawnee, leaving only a little territory for the Ponca. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was flawed because it did not honor the cultural differences between the Native Americans and the United States, notably the language barrier and different conceptions of what land ownership meant to both groups. As a result, the 1851 Treaty did not establish a lasting peace or effective resolution for conflicts over the land. In addition to writing treaties, the United States government sanctioned the extermination of bison herds to clear the land for settlement and for ranching. Because bison and cattle occupied the same spaces in the grasslands, they would not coexist well together. Additionally, the Native peoples of the area followed the bison, and the settlers would not coexist with the Native Americans either. As a result, the bison populations of the Great Plains were decimated, as millions of bison were slaughtered in a matter of decades. This destroyed many traditional Native lifeways and sent many tribes into poverty, as their cultures relied heavily on bison herds for food and supplies. While the 1851 Treaty established Pawnee rights to a significant portion of land near the Niobrara River, encroachments by settlers and the destruction of bison herds made it difficult to survive on their reservation. In 1857, the Pawnee ceded 14 million acres for $200,000 in annuities to secure their survival, leaving only a small reservation for themselves. They were later relocated to Oklahoma in 1877 with other tribes as the United States government sought to consolidate Native Americans in Indian Territory. Because the 1851 Treaty did not establish a suitable peace, war broke out between the United States government and the Lakota between 1866 and 1868. The Lakota ultimately won the war, and the resulting 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty established a large reservation, called the Great Sioux Reservation. This territory included land along the Niobrara River which the government had promised to the Ponca in 1858. The inclusion of this territory intensified conflicts between the Ponca and the Lakota, but the government did not respond to the Ponca’s requests for assistance until 1877 when they forcibly expelled the Ponca from the reservation to send them to Indian Territory in Oklahoma.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Phyllis Stone, Elder of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, tells stories of her family and tribal heritage and how the traditions of her people are enriched by the lands they care for. Early explorers James MacKay, a fur trader working for a Spanish company, visited the region in 1795 and 1796. He later described the sandhills as a “Grand Desert of moving sand where there are neither wood, nor soil, nor stone, nor water, nor animals, except some little tortoises of various colors.” Various army expeditions in the 1850s and 1860s explored possible wagon and rail routes, although no wagon trail was ever developed. Soldiering at Fort Niobrara The Treaty of 1868 created the Great Sioux Reservation north of the Niobrara River in Dakota Territory. Over the next two decades, the U.S. Army proceeded to surround the reservation with a ring of forts to monitor the tribes. Construction of Fort Niobrara, the southernmost of the forts, began in 1879 on a well-watered, well timbered site selected by General George Crook. This was close enough to monitor the Sioux, but far enough to avoid accidental friction between the tribes and the troops. The soldiers constructed a steam-powered sawmill to cut lumber and made adobe bricks. The fort was laid out in a standard military pattern with barracks and stables on one side of the parade ground and officers’ quarters on the other. The soldier's daily routines were relatively peaceful; soldiers drilled, worked at construction and maintenance of the fort itself and shipped beef and supplies to the Rosebud Reservation. The fort served as an embarkation point for troops responding to the Pine Ridge outbreak, which culminated in the Wounded Knee massacre of 1890. Among the units stationed at Fort Niobrara were the African American troops of the 9th Cavalry.

Vintage postcard courtesy of The Niobrara Council.

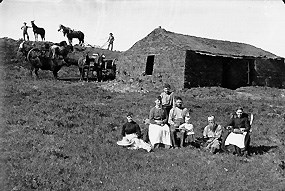

NPS photo - Homestead National Monument of America Homesteaders and ranchers Cattlemen from south of the sandhills were the first Euro-Americans to spend any great length of time in the sandhills and to extensively exploit the central Niobrara River area. In the 1870s, using Texas cattle, Mexican cattle-raising methods, and the free grass of the plains, a small number of men profited from the open range of the sandhills and the Niobrara River valley. They found a ready market at the military forts where the army purchased cattle to supply the Indian reservations. The deep ravines and canyons along the Niobrara River provided ideal places to hide stolen cattle, and cattlemen’s associations and vigilante groups were formed to curb the rustling. Federal and local regulations began to restrict the free range, but it took the farmer to settle the sandhills, change ranching, and convert a frontier to a state. While the eastern third of the state was populated in the 1850s, it would be another thirty years before the central Niobrara Valley was settled. Cherry County’s first homesteader, Charles Sears, staked his claim ten miles east of Valentine and received his patent in 1886. Niels Nielsen, a Danish immigrant, estimated that a sod house cost about $50 to build, and a wood-frame house cost $250 to build in 1889. $272 in materials would build the two miles of barbed-wire fence to enclose a 160 acre quarter-section homestead. Promoters and developers made dubious claims regarding the productivity of the land and amount of rainfall, leading to a high failure rate among homesteaders who tried their hand at dry-land farming.

The 20th Century One animal unit (cow and unweaned calf) requires from 10 to 30 acres of grazing in this rangeland, so a traditional 160 acre homestead could only support from 5 to 16 head of breeding stock – not a profitable number. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Kincaid Act, increasing the size of a western Nebraska homestead to 640 acres, a full square mile section. This acreage proved more practical for the type of prairie range present in the area, and made ranching a more attractive prospect than attempting to grow crops. Between 1900 and 1935, the average sandhills ranch had doubled in size from 640 to 1280 acres. However, as ranches increased in size to over 4000 acres by the end of the 1900s, population steadily declined, with 1990 census counts lower than those of 1890. In some respects, the area is returning to its frontier phase as sparsely populated rangeland.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Debby Galloway tells stories and tales of the years when men and women from all corners of the United States were seeking homestead claims of free land in the West. She traces her genealogy through these homesteaders and illustrates how the spirit of the Nebraska Sandhills along the Niobrara River have captured her heart.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Steve Breuklander tells the story of how his family became one of the first river outfitters in the Niobrara River Valley and explains how outfitting and ranching complement each other as parts of the modern economic structure of the region. |

Last updated: September 15, 2025