|

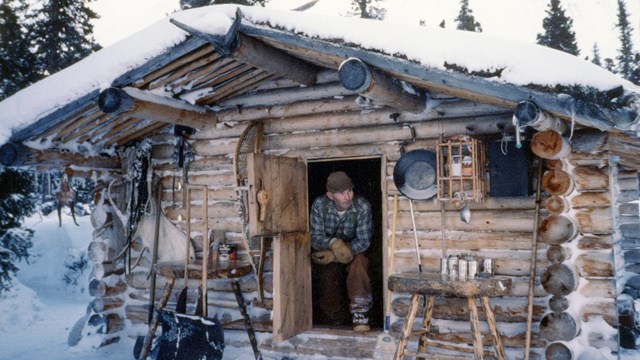

Proenneke's wilderness ethic was simple: Twin Lakes and the wildlife therein should not suffer for his presence. He reused almost everything, even carefully crafting buckets and storage boxes from used gas cans.

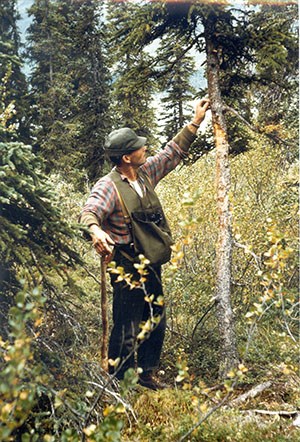

Photo courtesy of Raymond Proenneke From Hunter to Conservationist Proenneke's evolution from sport hunter to subsistence hunter to non-hunter seems to have been part and parcel of a fairly common feature of the maturation process of many American hunters. Writer-ecologist Aldo Leopold is most eloquent in his book A Sand County Almanac when he recounts a similar journey of personal growth to that of Proenneke's when he speaks of shooting wolves in Arizona in the early twentieth century. "In those days we had never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf. In a second we were pumping lead into the pack ... When our rifles were empty, the old wolf was down, and a pup was dragging a leg into impassable slide-rocks . . . We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes-something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters'paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view." - Aldo Leopold, p130

Two other hunters of the "Greatest Generation" of WWII vets who lived around Lake Clark for a number of years also underwent the same journey from youthful younger to older conservationist: the late Jay Hammond and Allen Woodward. Hammond, a big game guide and former U.S. Fish and Wildlife predator control-pilot, and Woodward, an ardent sport hunter both traveled the same trail as Proenneke and Aldo Leopold did, as they aged they much preferred to observe wildlife alive as opposed to simply looking at them as food for the table or trophies on the wall.

NPS photo Nothing Wasted Proenneke's account of his one and only Dall's sheep hunt between October 22 and October 25, 1968 is chronicled in his own words in the book The Early Years: The Journals of Richard L. Proenneke 1967-1973 between pages 159 and 162. Proenneke's account stands out for its clarity and candor and is very much in keeping with the very highest ideals of American utilitarian hunting traditions. Proenneke just about completely consumed the entire ram, eating the meat, rendering the tallow and using sections of the sheep hide for canoe seat covers. After the fall of 1978 when the Twin Lakes area became part of Lake Clark National Monument and sport hunting was forbidden, only subsistence hunting for local qualified residents of five subsistence zoned villages was permitted. On December 6, 1980 Congress passed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act which created 48 million acres of new national parks, including the 4 million acre Lake Clark National Park and Preserve. Apparently Proenneke ceased hunting after that time, but he continued to salvage any game meat that had been killed by sport hunters who violated the law and who, in Proenneke's opinion, had not salvaged all the edible meat. This was in keeping with what he had been doing since he first moved full time to Twin Lakes in the spring of 1968: cleaning up after hunters who did not sufficiently salvage kills before they rotted or bears claimed the carcasses. The only exception to this may have been the occasional porcupine he killed, and often ate, that chewed his or other cabins around Twin Lakes. Even before the National Monument designation had been declared by President Jimmy Carter in December 1978 Proenneke had been growing increasingly disenchanted by sport hunters and guides who only salvaged parts of caribou and moose, such as the four quarters and back straps. Proenneke felt it was necessary for hunters to salvage as much of the edible meat as was possible, including the neck, ribs and tenderloins in order for the animal to be completely legally and ethically harvested. He saw several instances of sport hunters simply taking the four quarters from caribou and then hiding the dismembered carcasses beneath the branches of spruce trees. Proenneke grew so assertive in his opposition to wanton waste of game animals that he risked open verbal confrontation with people who he had previously been on cordial terms. Increasingly he was running out of patience even with old friends who only salvaged a bare minimum of the meat. Sharing the Surplus Proenneke was fortunate that the Alsworth Family brought in his groceries and mail over the years. His diet was mostly oatmeal, sourdough hot cakes and biscuits, bacon, eggs, beans, and just about anything else friends brought him along with the fish he continued to catch. He still enjoyed eating meat, but as the authority of the National Park Service was established in the 1980s and 1990s Proenneke had few opportunities to salvage illegal kills simply because there was no legal hunting occurring around Twin Lakes. The ever resourceful Proenneke had one last trick up his sleeve, though. One time in the early 1990s he located a wolf-killed moose carcass and was able to glean a few edible portions of meat from the carcass. Not long after park staff stopped in to check on the elderly Proenneke during a routine patrol of the park. He invited them in his cabin and promptly offered them bowls of moose meat soup while recounting how he happened to come by the fresh meat. Inspiration Proenneke's off-the-grid lifestyle resonates with people around the world. His observations are the basis for several books and videos, which in turn, have inspired people from around the globe to live more simply, to take closer notice of the natural world around them, and to explore the Twin Lakes region.

One Man's Alaska

Filmed in 1977, this 27 minute long documentary can be viewed online for free at the National Archives website.

No Place Like Twin Lakes

Watch Proenneke's last visit to his cabin at Upper Twin Lake in the year 2000 at the age of 84.

Explore Lake Clark's Museum Collection

View Lake Clark's entire online museum collections which includes some of Richard Proenneke's belongings.

Richard Proenneke Journal Collections

Proenneke was a tireless writer, documenting his observations in a series of journals that span nearly 30 years.

Learn about the Proenneke Cabin

Proenneke's cabin at Upper Twin Lake stands out for the remarkable craftsmanship that reflects his unshakable wilderness ethic. |

Last updated: October 28, 2019