|

The Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-1898 was over almost as soon as it began. During two years, thousands of people traveled from the coast to Dawson City. This influx had a lasting impact on the landscape and native people along the route north.

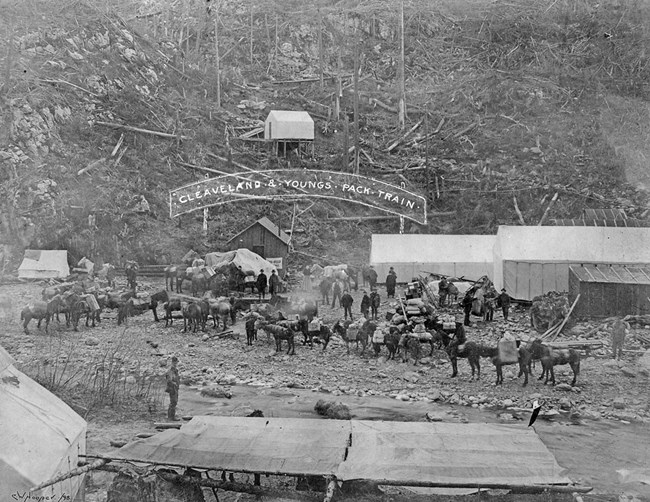

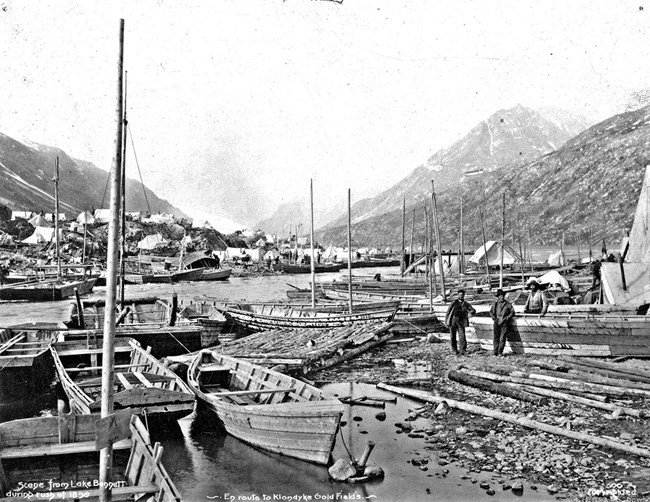

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library CC-81-8838. Changes along the Chilkoot TrailTlingit people have used the Chilkoot Trail for hundreds of years as a trade route. This corridor, between Dyea and the Interior, allowed them to trade with Tagish communities. The trail was well established, but the Tlingits limited the number of people using it. During the gold rush thousands of people began using the trail. As they traveled this narrow valley, they had a huge impact on the land. These gold seekers transported their required "ton of goods" using every means possible. Pack animals, carts, sleds, human strength, and elaborate tramways were all used. It was impossible for anyone to move their supplies to Lake Bennett in one trip. Camps appeared along the trail as stampeders moved their gear. Stampeders cleared areas to set up tents, businesses, and shelters in these new camps. Camps consumed an enormous amount of trees. Hundreds of people used wood as fuel to cook their food. Timber was used to build the rough frames for tents, saloons, restaurants, and hotels. As camps developed into small cities, the forest around them began to disappear. At the end of the trails, stampeders reached the shores of Lake Lindeman and Lake Bennett. At the lakes they needed more lumber than ever. In additions to fueling stoves and building structures, they also had to build boats. During the winter of 1897-98 stampeders built over 7,000 boats. Sawmills popped up on the lake shores as they began cutting down the trees closest to the lakes. As more people arrived, newcomers had to search farther away to find trees to harvest.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55690. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. Deforestation and Erosion Change the Aquatic EcosystemsWithout the forest, other things began to change along the trails. Deforested hillsides easily erode. Roots and moss hold soil in place. Without them, dirt washes off in rainstorms and flash floods. Deforested hills are more prone to landslides. The runoff from hills into streams harms aquatic ecosystems. Aquatic plants can grow out of control from extra nutrients in the runoff and choke the water flow. Silty water hampers the growth of aquatic insects, and the survival of fish species.Fish struggle with sediment-filled water. It makes them hard to see their predators and prey and clogs their gills making it hard to breathe.

Erosion was not the only aquatic problem during the Klondike Gold Rush. Human and animal waste, rotting horse carcasses, and trash also polluted waterways.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library TS-202-8868. Transportation ResourcesIndividual stampeders were not the only ones looking for timber. Steamboats began transporting people and supplies up and down the Yukon River. Their engines required cords of wood to propel the large boats, especially going upriver. A cord of wood is a pile of logs four feet wide, four feet tall, and eight feet long. The most convenient timber grew along the Yukon River. On the trip to Dawson, steamships would stop at lumber camps along the river. Often these camps belonged to First Nations people in the Yukon.

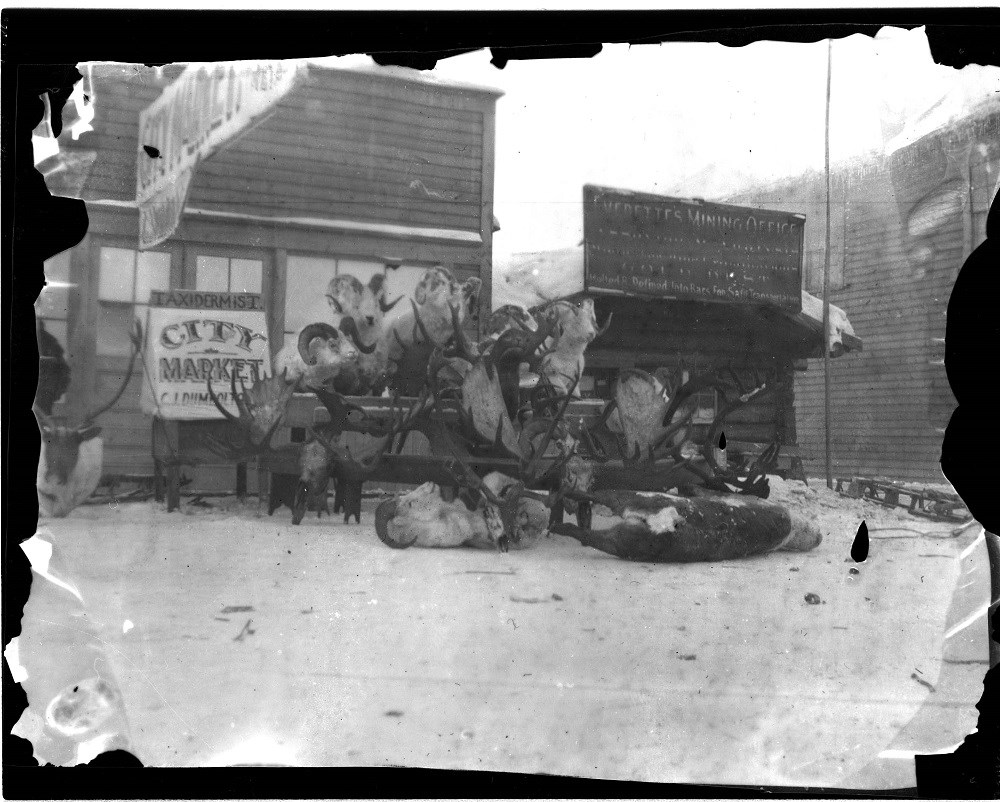

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Hooper Collection, KLGO 95. Over-harvestingStampeders did not encounter an uninhabited, untouched environment on their journey to the Klondike. Alaska Native and First Nations communities existed in the area for thousands of years. They had their own hunting and foraging traditions. The number of stampeders overwhelmed the available resources. Stampeders tried new, local foods. Rose hips, mushrooms, berries, and goose eggs became part of their diet. Stampeders hunted local game. What once was a seasonal hunt turned into a year-round activity. Moose, caribou, mountain goats, and other animals were all harvested. As people hunted, local animal populations disappeared. Anyone hunting had to travel farther to find game. For First Nations hunters, this meant altering traditions.

The exact numbers moose and caribou consumed are unknown. Historian Robert McCandless estimates that Dawson City had about 9,000 people in 1904. His educated guess is that this population consumed 900 moose and 2,300 caribou a year. This population was much smaller than at the height of the gold rush. In 1899-1900 Dawson City's population was about 20,000 people. Consuming moose and caribou at the same rate, 1,800 moose, 4,600 caribou were killed. We do not have estimates for other harvested species like mountain sheep, bears, and ptarmigans.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library DVY-140-10533. Early MiningEven the first miners in the Klondike Gold Rush had an impact on the environment. As more miners arrived to the area, they used more natural resources and the impact increased. Mining activities became a year-round activity. Miners adapted to winter conditions to continue mining. Underground fires softened frozen soil, but added an element of danger. If the earth thawed too much, then the mine shaft could collapse. Fumes from the fire could also be deadly. Any fire required timber to feed it. In the summer, miners re-routed streams into above ground sluice boxes. The diverted water in the sluice boxes washed the gold from the mined gravel. This engineering changed the natural flow and locations of streams. Once gravel was stripped of gold, it was placed into a huge waste pile. These waste piles are known as tailings.

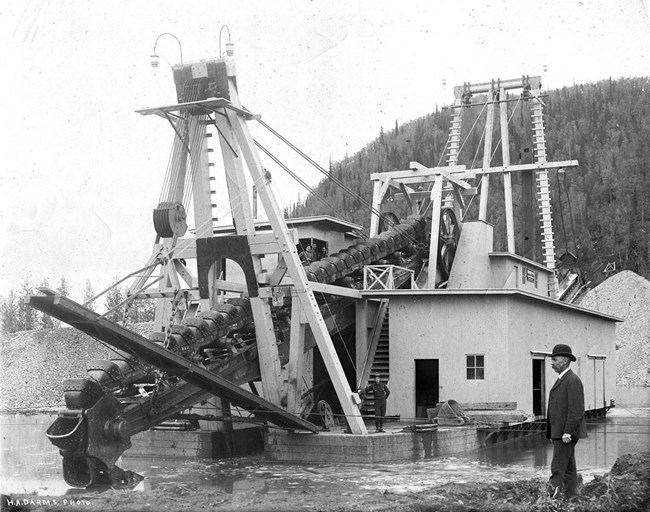

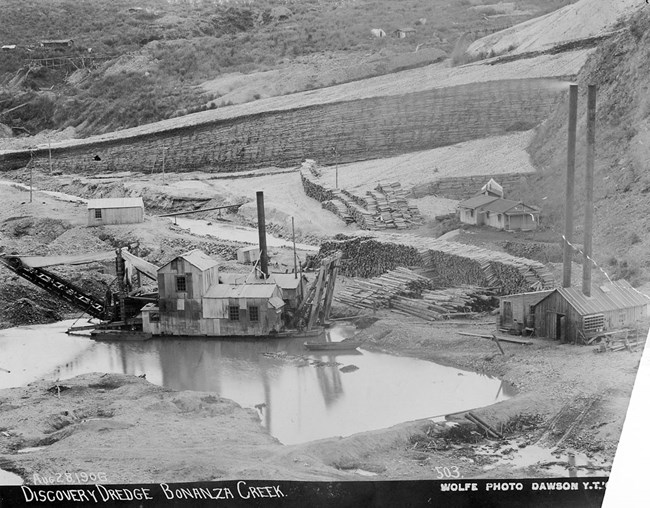

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library DVY-115-8854. Gold Dredges Arrive in the YukonIn the early 1900s, dredges arrived in the Yukon. Dredges allowed people to mine on a much larger scale. A chain of huge buckets scooped material up and dumped it onto a conveyor belt. Next, a large volume of water washed any gold out of the soil. Tailings of waste gravel and dirt piled up around the dredges.These piles remain today in the Klondike. They are visible reminders of the major human-caused landscape changes. The first dredges were powered by steam, requiring tons of cordwood for fuel. Much of this wood came from the hills surrounding the mining areas. After just 10 years, the Bonanza and Eldorado Creek areas were bare and deforested. In photos the hills appear almost lifeless. Katherine Morse observed "[g]old seekers stripped vegetation from the earth, rerouted streams, and completely altered long stretches of stream valleys. In order to produce gold, they consumed whole ecosystems, or rather the pieces of whole ecosystems, broken into constituent parts in the form of endless piles of wood and dirt and carefully channeled streams of water." On-going Mining and Landscape RecoveryThe Klondike Gold Rush left scars on the landscape that are still healing. Some places, like the Chilkoot and White Pass Trails, have recovered greatly. Other places, like the Klondike mining area, are still changing. Gold mining still takes place outside of Dawson City. Modern mining often uses chemicals like cyanide to separate gold from other minerals. These chemicals can filter into human water sources and the broader environment. They are harmful to humans as well as plants, animals, and ecosystems. The Klondike Gold Rush is often cited as an important step in opening "the last frontier." But it had lasting effects for the people, plants, and animals who were here before the rush.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library DVY-108-8827. References:The Nature of Gold, an environmental history of the Klondike Gold Rush, by Katherine Morse Gold Fever: Race to the Klondike! (park movie) Nature of Southeast Alaska, by Richard Carstensen, Robert H. Armstrong, and Rita M. O'Clair |

Last updated: July 25, 2024