|

Plants > Chestnut blight

NPS photo. There are many great partnerships in science. Watson and Crick worked together to describe DNA. Crocodiles invite tiny plovers to clean their sharp reptilian teeth and get a meal. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, scientists are investigating another type of relationship: a virus that may help trees overcome the deadly chestnut blight. For centuries, the flanks of the Great Smoky Mountains were crowned with towering American chestnut trees. Chestnut blossoms were so thick in spring that the mountains looked coated with snow, and prickly chestnuts piled so deep in fall that people stood up to their knees in the crop. The chestnut blight, caused by a fungus accidentally introduced from Asia, changed everything. By the 1940s the blight had killed an estimated four billion American chestnut trees nationwide. Where before about a third of all trees in the Smoky Mountains were chestnuts, today even single spindly saplings are rare. For the past few years, a research team from West Virginia University, headed by Bill MacDonald and Mark Double, have been collecting samples of the chestnut blight fungus to search for strains of the virus that helps chestnuts. The morning the researchers arrived this fall was drizzly and fog-swirled, making chestnuts hard to spot in the brown understory. Yet they hiked into the mountains optimistically, splitting into teams with Forest Insect and Disease Specialist Glenn Taylor. They checked each chestnut they found for orange bumps, signs of the blight itself.

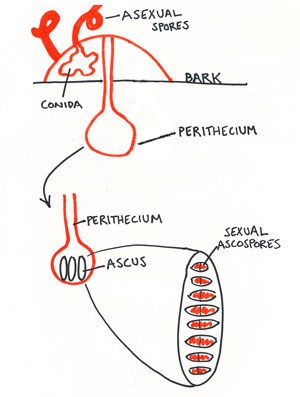

NPS drawing. The fungus forms open sore-like cankers on the tree's trunk and branches, cutting off nutrients from the soil. Soil microorganisms protect the tree's roots, so the chestnut sprouts again and again where the long-dead trunk stood. Few chestnut sprouts make it to be much thicker than your wrist before the blight re-infects them, unless the tree happens to also host a helpful organism called a hypovirus. The discovery of hypovirulence Where did this virus come from? We aren't sure, but it was discovered only after the blight had destroyed American chestnut forests and European orchards. Antonio Biraghi, an Italian pathologist, happened to spot mature chestnut trees with the characteristic orange fungus still growing in an abandoned orchard. Biraghi inspected cankers under the microscope and saw this fungus looked different from any he had seen before. Two decades later, researchers from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station identified what made it so distinct: a virus entwined with the fungus, infecting it and weakening it. With the virus' help, trees had time to react by growing a protective bark layer over the canker. For the first time, there was hope for potential recovery of the chestnut tree!

NPS photo. Spreading the good hypovirus? Since Biraghi’s discovery, scientists have tried to replicate the success that he saw in those orchards, without much luck. So far, it seems the virus doesn’t work when it's moved to different trees. In addition, there are many different strains of the virus itself, and each attacks only a specific type of the fungus. This is where the West Virginia University researchers come in. They hope to find answers to a few key questions:

To answer the many questions about the hypovirus is a long project, but the work in the field this day was surprisingly simple. Using what looked like a hollow meat thermometer (what was actually a bone marrow extraction tool), the researchers jabbed into the center of each canker, taking a bark sample and with it, a core of the fungus itself. They had a small collection tray ready to catch each bark sample, then carefully labeled the samples and photographed the site before searching for the next tree.

NPS photo. All in all the research team collected dozens of canker samples. Back at the lab, they will scrape the bark samples and spread the tiny spores from the chestnut blight fungus on petri dishes filled with agar (a vegetable gel similar to gelatin). As this culture grows, they'll be able to see if the hypovirus existed in any of the chestnut tree cankers. Eventually they will understand not only the blueprints of any helpful hypovirus that exists, but also how they can help more chestnuts survive. Chestnut blight isn't going away, and in the Smokies, at least, it does not appear that hypoviruses can effectively control the disease. Year after year, however, hypovirus research, combined with efforts by the American Chestnut Foundation to crossbreed more resistant trees, will help us plan a future for American chestnut trees in the Smoky Mountains. Return to Plants main page. |

Last updated: October 12, 2017