With the creation of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, hundreds of families were asked to move out of their mountain homes. Some went willingly, and others fought against it, but most families moved immediately. A select few, including the six unmarried Walker sisters, received a special lifetime lease—a chance to live out the rest of their lives in the log cabin they were raised in, even after the creation of a national park. Their incredible story is one of strength, hard work, and a love for the land of the Smokies.

Early Days on the Homestead

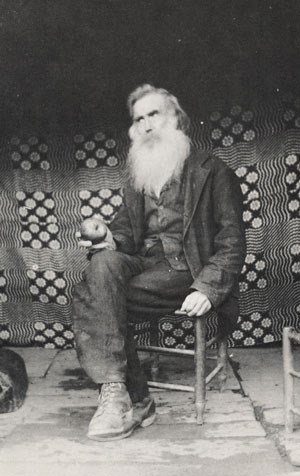

The sisters' father, John N. Walker, married Margaret Jane King in 1866 shortly after returning from the Civil War, where he fought for the Union and was imprisoned by the Confederacy. After marrying, John Walker obtained a house and property in Little Greenbrier Cove through Margaret's family, later expanding his land by buying out her brothers and sisters. The house was made of logs from tulip-poplars, insulated with mud and rock. Other buildings on the Walker property included a barn, corncrib, smokehouse, pig pen, apple barn, and blacksmith shop. A springhouse situated on a nearby flowing creek kept dairy products such as milk and butter cool throughout the year, as well as provided storage room for pickled root vegetables.

An innovative man, John crafted ladderback chairs, looms, tools, and a small cotton gin. He also planted orchards that included more than 20 kinds of apples, as well as peaches, cherries, and plums. Chickens, sheep, goats, and hogs were all raised on the farm.

Family of Thirteen

Together the Walkers raised eleven children—seven girls and four boys. All eleven children reached maturity, and given the time period and its lack of medical care, this was an extremely rare case. The sisters, from oldest to youngest, were Margaret, Polly, Martha, Nancy, Louisa (pronounced Lou-EYE-za), Sarah Caroline, and Hettie.

In 1881 John Walker and his son, James Thomas, helped build a small, log schoolhouse at the center of the growing Little Greenbrier community. It would also double as a Primitive Baptist church until 1925. Because there was so much work to do on the farm during the warm seasons, class was held in the winter for two to three months. School was a privilege; it was a chance for children to learn, see their friends, and escape their chores for a little while. Lessons included spelling, arithmetic, reading, and writing.

The Walker boys left home or married, while only one of the seven sisters—Sarah Caroline—married. The other six unmarried sisters stayed in Little Greenbrier with their father and inherited the farm after his death in 1921. He was 80 years old. One of the sisters, Nancy, died ten years later, and the remaining five sisters began to establish their life on the farm. They fed and clothed themselves, raised livestock, and maintained their mountain homestead for over forty more years.

The sisters were also excellent spinners and weavers. Wool from their sheep was washed, carded, and spun using a spinning wheel, sometimes dying the yarn with berries or bark. They then wove the skeins of yarn into fabric. Flax and cotton were also grown at the Walker sisters' farm to produce their own textiles using the cotton gin that their father had built. The linsey-woolsey blend cloth created was used to sew their own clothing. Following in their mother Margaret's footsteps, the daughters also kept a herbal garden for mountain remedies, including horseradish, boneset, and peppermint for healing teas. Natural plants in the forests were collected, too. The Walker sisters once said, "Our land produces everything we need except sugar, soda, coffee, and salt."

The Beginning of a National Park

In 1926, Congress approved authorization of the park, allowing North Carolina and Tennessee to start raising money to buy nearly half a million acres, most of which was privately owned. Parcels of land collected from families and timber companies alike were bargained for, haggled over, and eventually purchased, including the Walker sisters' 122-acre homestead. Refusing to leave their mountain home, the sisters held out until 1940, when President Roosevelt officially dedicated Great Smoky Mountains National Park from a stone memorial at Newfound Gap. With the creation of the park, the sisters received $4,750 for their land as well as the opportunity to live out the rest of their lives at their home through a lifetime lease.

But living in the national park meant traditional practices such as hunting and fishing, cutting wood, and grazing livestock were now prohibited within the park boundaries. A new lifestyle developed for the sisters. Visitors flocked to the park and visited what became known as "Five Sisters Cove". The Walkers welcomed the curious newcomers and saw them as an opportunity to sell handmade items such as children's toys, crocheted doilies, fried apple pies, and even Louisa's hand-written poems.The sisters were even featured in the Saturday Evening Post in April 1946, showcasing their mountain lifestyle to the rest of the country.

NPS photo Though the Walker sisters are now gone, their legacy lives on through their homestead, the objects they created and lived with, and the neighbors and visitors they interacted with well into the 1950s. By parking at Metcalf Bottoms, you can take the short half mile walk up to the Little Greenbrier schoolhouse, which John Walker and his son helped build. If you're up for a little more, take the Little Brier Gap Trail a mile up to the Walker sisters beloved home. Stand on the porch and imagine what life was like for the five sisters when they trapped food in the forest, tended to their gardens and livestock, and openly welcomed visitors before and after the park was established. New visitors will not be greeted by fried apple pies, but instead by a reminiscent, peaceful atmosphere that surrounds the now-vacant homestead of the Walker sisters.

Written by Lindsey Taylor.

|

Last updated: October 7, 2025