|

I observed a group of middle school students boisterously approach Mather Point, jabbering away as only young adolescents can. One boy was particularly loud, laughing, cracking jokes, completely unaware of his surroundings. When they reached the top of the stairs and caught their first glimpse of the vastness before them, the group stopped and quieted as one. “Whoa,” the boy mumbled. Ted Barone – Volunteer-in-Parks Photographer and Curator To navigate through this exhibit, please click on the photograph next to each section description and then move the sliders to compare the historic and modern photographs.

Sacred CanyonAs a white person, I have grappled with the idea of the Grand Canyon as a sacred place. I feel the Canyon’s power, especially as I descend into its interior and experience the changing light, texture of the rocks and soils, and weather. But my experience is only temporary. For the indigenous people of the Canyon region, the rocks, trees, floods, and animals are all sacred and integral to who they are. As indigenous scholars Danelle Cooper, Treena Delormier, and Maile Taualii wrote in the International Journal of Human Rights Education in 2019, “Our environments are our cultural identities, origins, religions, and worldviews.” For me, my family, my ancestors, and my environments are my sacred spaces. They define who I am, how I think, and how I live my life in the world. In the same vein, as Cooper et al note, “In plain speak, to have a relationship with a place and to know this place for Indigenous/Aboriginal People is similar to knowing and relating to one’s family.” Researchers from the University of California have determined the presence of the Pai people in the Grand Canyon region dates back 20,000 to 25,000 years. For the Havasupai, Hualapai, and Yavapai-Apache Nation, along with the rest of the 11 Associated Tribes of the Grand Canyon, the Grand Canyon is a sacred place. “The whole canyon and everything in it is sacred to us, all around, up and down.” (Rex Tilousi, Havasupai). For the Hualapai, Hopi, and Zuni, it is the location of their origin stories. For all, the ancestors play an integral role in their contemporary ceremonies. As any student of American history knows, the post-contact history is one of betrayal, broken treaties and forced relocations of indigenous peoples by the European-Americans, and the commercialization of the western idea of Indians. As a European-American, I have long been sickened by that history. However, the more modern history is one of re-empowerment of tribal organizations and reclaiming of ancestral land. At the Grand Canyon, this process has begun, most notably with the Desert View Tribal Heritage Project, and I am hopeful for the future.

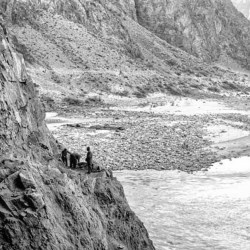

The Explorers: Surveyors and River RatsIn 1857, the War Department assigned Lt. Joseph Christmas Ives to explore whether the Colorado River would be useful to transport troops and supplies to Utah to fight the Mormon War. Ives determined the river to be unnavigable for military purposes and the region to be “altogether valueless … (It) shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.” It was an almost laughable historical miscalculation. Over the next 80 years the forces of Manifest Destiny, the search for rail routes, and extraction of resources belied Ives’ claim, overwhelming the Grand Canyon region’s indigenous populations and ecosystems.T ruth be told, those explorers were not the first to tread upon the Canyon landscape. The indigenous people of this sometimes harsh and unforgiving region had established trails, farms, trade routes, and villages thousands of years before Ives came along and declared it “unvisited.” Notwithstanding Ives’ mistaken assessment, I remain in awe of the bravery and fortitude of both the indigenous people and the early European-American explorers. As I search for the exact locations to replicate archival photographs, I have at my fingertips maps produced with global satellite technology, up-to-date weather reports, and the guidance of Grand Canyon veterans. Ives and other exploreres such as Powell, Matthes, and Stanton had few such resources. They were, in fact, the ones who established the baseline for most of those tools we use today.

The Rocks - Miners and MoonshotsThe typical visitors to the Grand Canyon approach the rim and are overwhelmed by the dimensions of the panorama that opens before them. It’s too much for the brain to hold and comprehend. To my mind, the only way to even begin to comprehend what this “ditch” is all about is to get down into it, to touch the rocks which are a timeline of geologic history, feel the thermoclines and the heat rise as one descends, step across the dry streams and imagine boulders scouring the land, swept along by the floods that occasionally rush down the canyons.

Building the National Park

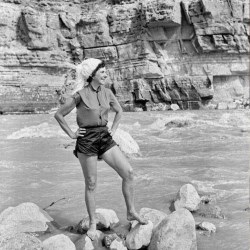

Tourism for the RuggedOne of the most enjoyable aspects of creating this Then & Now exhibit is to stand in the exact location a historic photographer stood and try to imagine what they saw and heard, what they were thinking, and how they felt. The modern visitor can come and go with relative ease and comfort, but not so with those who arrived around the turn of the 20th Century. Their journeys were long and arduous.

Rails and RoadsAs a tourist, getting around the South Rim of the Grand Canyon these days is pretty darn easy. You have excellent roads to get to fantastic views and hikes. In the village, you don’t need a car because you can walk or take a frequent bus to more amazing places.Such was definitely not the case in the early 1900s - no Interstate highway system back then. For the (mostly) white Americans and Europeans who chose to make the journey, jarring, hardscrabble roads and trails were their manifest destiny.

Tourism: Designs for the Leisure Class

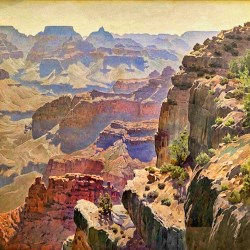

Artistic InterpretationAs stated in the introduction to this exhibit, there just aren’t the words to describe the magnitude of time and light that is the Grand Canyon. It’s an ever changing landscape. Shadow angles adjust to the sun as it moves across the sky, storm clouds multiply dimensions, dust and smoke cast a haze that softens the jagged edges of the temples and thrones in the distance. In that context, it is the artist’s task to interpret and capture the mood, the scale, and the texture of the Canyon – an enviable task! |

Last updated: November 3, 2023