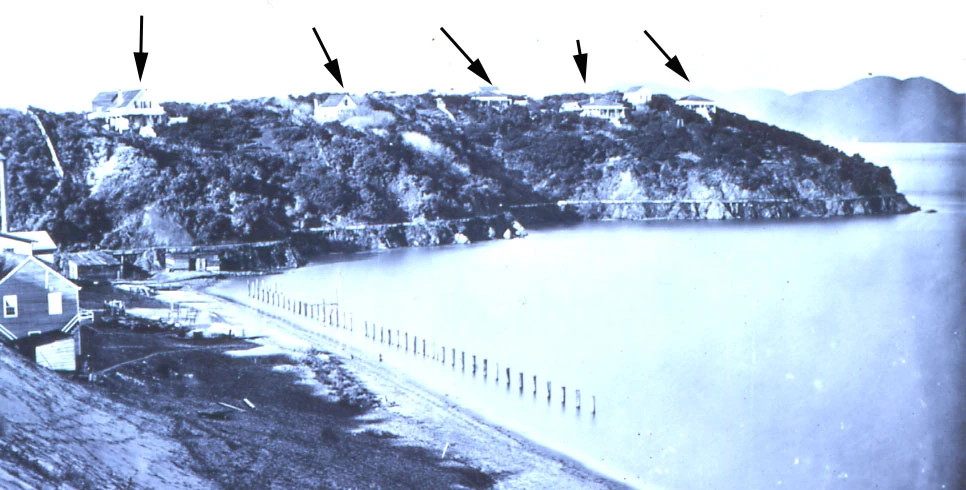

PARC, NPS Defending the Bay Fort Mason, located on a hilltop promontory, was an excellent location for harbor defenses because the promontory commanded not only the cove, but the passage between the mainland and Alcatraz. Over the past 200 years, it has been fortified by the Spanish, the Mexican and the United States military. During the Spanish and Mexican periods, the governments recognized it as an ideal spot to fortify; in 1797, the Spanish built the Bateria de Yerba Buena, equipped with five eight-pounder cannons. After the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846, the United States took control of California, and three years later, gold was discovered in California. In a very short period of time, San Francisco had evolved from a sleepy port town into a very rich and profitable city; a city within a state that the U.S. government now had great interest in protecting. Every day, American ships laded with gold were passing through the Golden Gate straits on their way around Cape Horn and finally onto Washington, DC., where the money would be deposited into federal banks. The government needed to guarantee the safety of these ships to ensure that the money reached its final destination. In an effort to protect what was now theirs, in 1851 the U.S. Army established this overlook area as a United States military reservation, designating it Point San Jose. Civilian Neighborhood at Black Point However, while the army officially reserved the land, the War Department did not initially build any buildings or station any soldiers here. For a long time, the land remained vacant. Meanwhile, “gold rush fever” drew people from all over the world to California to seek their fortune. Practically overnight, San Francisco swelled into a major city. Forced by the city’s population explosion and subsequent housing shortage, ambitious real estate developers quietly moved onto the military land and began to construct their own private homes. For the next 10 years, until the outbreak of the Civil War, Fort Mason (known to the locals as “Black Point”) became home to a group of wealthy, well-educated civilians, many who were committed to the anti-slavery movement. The Black Point community included John Fremont (of the Bear Flag Revolt), his influential wife Jessie Benton Fremont and Leonides Haskell, the politically well-connected real estate developer who was an abolitionist. It was at Haskell's Black Point home, where U.S. Senator Broderick died, after his infamous duel with David S. Terry that drew national attention fo the anti-slavery movement.

PARC, GGNRA

PARC, GGNRA The Army’s Point San Jose The outbreak of the Civil War forced the army to take back possession of Black Point, evict the civilian residents, and re-establish the original name, Point San Jose. Like most mid 19th century army posts, Point San Jose was laid out and constructed to function as a small, self-sufficient town. The main parade ground, an open grassy square dedicated to drills, marches, parades and public ceremonies, was the physical and organizational center of post life. The most significant military buildings, like the post headquarters, the hospital, the barracks and the mess halls were constructed on a rectangular grid around the main parade ground. Point San Jose was different than other posts in that the army officers’ were stationed in the former Black Point civilian homes instead of living near the main parade ground. Because the Union government feared possible Confederate attacks against commercial sailing ships and their gold cargo, the army continued to strengthen the harbor defense structures. In 1864, the army fortified Point San Jose with more guns. In 1882, the post was renamed Fort Mason to honor Colonel Richard Barnes Mason, the second military governor and commander of California.

|

Last updated: July 10, 2019