photo courtesy of the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library The Battle for Freedom in California By the late 1850s, the State of California had become a focus of the heated issue of slavery. Its population stimulated by the Gold Rush, California was now home to people from the North—often referred to as free-soilers—who were against slavery, and transplanted Southerners who supported the institution of slavery and called themselves the Chivs (for chivalry). Many Southerners also passionately felt that, if need be, Southern states should be able to secede from the union, to preserve slavery and the larger concept of states’ rights. The Gold Rush also brought both free African-American settlers, seeking their fortunes, as well as enslaved African-Americans, who were forced to dig for their owners’ benefit. As new states were added to the union, Congress tried to achieve a balance by carefully admitting an equal number of as slave states and free states. After much bitter national debate, California entered as a free-state, part of the so-called Compromise of 1850. However, its vague antislavery constitution was open for extensive interpretation. And because people of color could not testify for or against a white person in a court of law, both African-Americans and local Indians were vulnerable to a white-only court system.

PARC, GGNRA “Free Soilers” living at Black Point, Fort Mason In 1850, President Fillmore established a military post here on the land now known as Fort Mason. However, the army maintained no military presence here and civilians quickly moved onto the prime real estate. By 1855, Leonidas Haskell and George Eggleton, both San Francisco real estate developers, had constructed at least five large, private homes at Black Point, all facing the San Francisco Bay. These decorative and expensive homes attracted the city’s newly-emerging middle class and for the next few years, Black Point became the preferred location for San Francisco’s elite and well-educated bankers, merchants and literary figures. Leonidas Haskell, Black Point’s developer, was both a free-soiler and politically well-connected. He helped shape and direct the political leanings of the civilian community as it became home to a small but influential group of white residents who were openly hostile to secession and slavery.

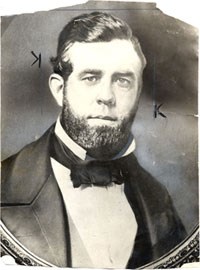

San Francisco History Center, The Opposing Politics of David Broderick and David Terry David Colbreth Broderick was born in 1820, the son of an Irish stone cutter. In 1846, after an unsuccessful attempt for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, he moved to California’s Gold Country to seek his fortune. After achieving business successes in minting and real estate, he became a member of the California State Senate from 1850 -1851. In 1857, he was elected a Democrat to the United State Senate at a time when the Democratic Party of California was sharply split in two, between the pro-slavery group and the “Free-Soil” advocates. Broderick was staunchly opposed to the expansion of slavery and worked closely his political friends, including Leonidas Haskell, to support the anti-slavery movement.

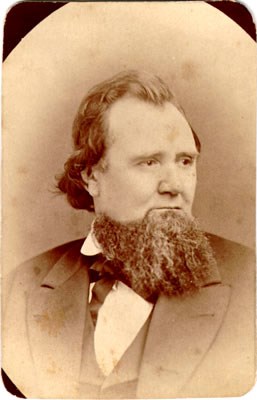

San Francisco History Center, David S. Terry was a Chief Justice of the California State Supreme Court and an advocate of extending slavery into California. Having previously stabbed a political member in 1856, Terry was man known for his hot temper and tendency toward violence. Although Terry and Broderick had been friends, when Terry lost his re-election because of his views on pro-slavery, he blamed David Broderick for his loss. At a party convention in Sacramento in 1859, Terry gave a searing speech, attacking Broderick and his antislavery stance. Broderick responded to Terry with an equally unflattering statement and as tempers flared, Terry challenged Broderick to a duel.

San Francisco History Center, The Deadly Duel At the time of Terry’s challenge, duels were illegal in San Francisco. They had originally scheduled the duel for a few days before September 13, but there was too large a group of witnesses and the duel was shut down by the city police. On September 13, they secretly moved the duel located to Lake Merced, just south of the city line. The chosen weapons were two Belgian .58 caliber pistols. Broderick was unfamiliar with this type of gun mechanism, while Terry, in contrast, spent the previous days practicing with this gun. At the moment of the duel, before the final “one-two-three” count, Broderick’s gun misfired into the dirt. He then stood tall as Terry aimed directly at Broderick’s chest and fired. While Terry later claimed to have only grazed him with a flesh wounded, his bullet entered Broderick’s chest and lung. The wounded Broderick was rushed to Leonidas Haskell’s home at Black Point. Despite the doctor’s best efforts, he died in that house three days later, reportedly saying “They killed me because I am opposed to the extension of slavery and a corrupt administration.”

Broderick's Legacy The San Francisco duel drew national attention. Senator Broderick's death turned him into a martyr for the anti-slavery movement. Terry and his southern sympathizers were accused of assassination. The Broderick-Terry duel reflected the nation's larger and more violent divisions and many feel that this tragedy pushed the country further towards a civil war. Senator Broderick's San Francisco funeral was attended by thousands of mourners and Senator Edward Dickinson Baker (for whom Fort Baker in Sausalito was later named) gave the moving eulogy. The City of San Francisco erected a large monument in Laurel Hill Cemetery and named a downtown street "Broderick Street" in his honor. Leonidas Haskell's house at Fort Mason, now known at Quarters 3, still stands today. While the house is not open to the public (park tenants live in the building), visitors can walk down Franklin Street and see the house where David Broderick died in 1859. For More Information: To learn more about the anti-slavery movement and the Underground Rail Road, please visit Exploring a Common Past; Researching and Interpreting the Underground Rail Road. Also please visit the Aboard the Underground Rail Road; A National Register Travel Itinerary. To learn more about the history of Fort Mason, visit the Fort Mason page or download the Fort Mason History Walk; An Army Post at the Edge of San Francisco. |

Last updated: June 30, 2021