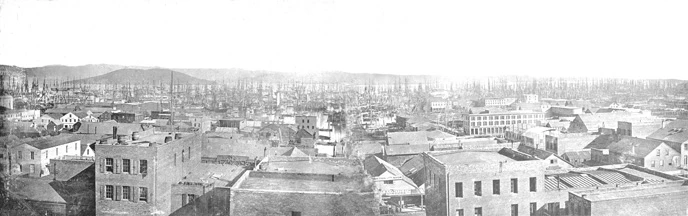

Photo courtesy of San Francisco Maritime NHP California’s Role Most people know about the great Civil War battles that were fought in the eastern and southern parts of the United States. However, many people are unaware of the significant part that California and Californians played in this epic struggle. California’s involvement in the American Civil War came in the form of strategy, logistics, and politics. The state of California played a valuable financial role as much of the Union government’s funding was supported by gold from California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. The state recruited volunteer soldiers so that regular soldiers could leave the western territories for the battlefields of the East. From California, the U.S Army maintained and built many forts along frontier trails, suppressed Confederate activity and secured the New Mexico Territory against the Confederate forces. Although California did not send organized regiments east, so many California citizens joined the Union Army that the 71st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was known as the California Regiment. The Issue of Slavery in California Though slavery is not often associated with California, slavery was a defining issue in the state’s early years under American control. After the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846, the United States took control of California from Mexico and ruled under American military governors. When gold was discovered along the American River in 1848, California was changed forever. As word of great riches in California quickly spread, gold-seekers from around the globe came to San Francisco and the city’s population exploded from 1,000 to a staggering 25,000 in just a few years. The United States had inherited the finest harbor on the Pacific Coast and needed to protect the harbor and its commerce from foreign threat and, with the Civil War, from domestic threat as well. California became a state in 1850 and the military quickly established posts and commenced fortifications at strategic locations, including Fort Point and Alcatraz. Its population stimulated by the Gold Rush, California was now home to people from the North, often referred to as free-soilers, who were against slavery, and transplanted Southerners who supported slavery and called themselves the Chivs (for ‘chivalry’.) Many Southerners passionately felt that, if necessary, Southern states should be able to leave the Union, to preserve slavery and the larger ideal of states’ rights. The Gold Rush also attracted both free African-American settlers, seeking their own fortunes, as well as slave owners who brought their African-American bondsmen to labor in the gold fields. As new states were added to the Union, Congress tried to achieve a balance by carefully admitting an equal number of slave states and free states. After much heated national debate, California became the 31st state, entering the union as a free state under the Compromise of 1850. However, the state’s new antislavery constitution failed to cover many specifics regarding slavery. Because of these ambiguities, California quickly became a part of the national slavery battle. By 1852 approximately three hundred black slaves worked in the gold fields. These slaves were brought over by southern slaveholders, who did not seem to fear bringing them into California even though it was technically a free state. In the early 1850’s, it was recorded that there were no more than 1,000 African Americans in all of California. However, by 1860, approximately 4,000 blacks lived in the state, most in San Francisco, Sacramento, and in mining towns in the northern half of the state. Some historians argue that California, and San Francisco in particular, should be considered part of the historic Underground Railroad, as this area was part of a large network of roads, stations, routes, and safe houses that helped enslaved people escape to freedom.

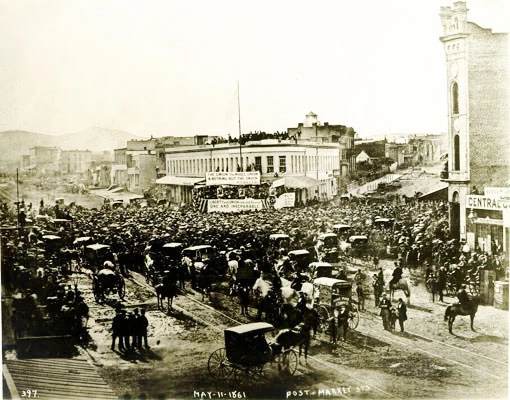

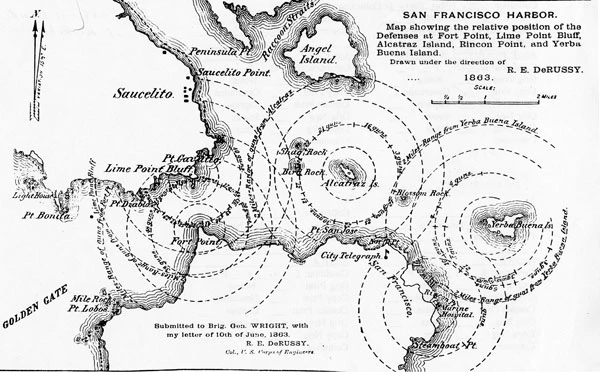

photo courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library Civil War Comes to California At the time of the war’s outbreak, California was still physically very isolated from the rest of the country. From the East Coast, California could only be reached by either a six-month cross-country trip or a dangerous voyage by ship around Cape Horn. While much of the country learned of the April 12th Confederate firing on Fort Sumter within hours, the news of war reached California 12 days later by Pony Express. After the attack on Fort Sumter, a wave of patriotism inspired many men to join volunteer regiments, most from pro-Union counties in the northern part of the state. Union supporters held large rallies all around the state, especially at Union Square in San Francisco which was named for the pro-Union activity that took place there. With the outbreak of the war, the U.S. government allocated additional military protection to the San Francisco area. As the war prompted an increased need for California gold to back the nation’s currency and control inflation, the shipments of gold out of the Golden Gate increased. In order to protect the great Bay of San Francisco, the military reinforced fortifications at Fort Alcatraz and Fort Point. The military had other reasons to protect the Bay Area. The U.S. Government was concerned about Confederate commerce raiders preying on steamships, sometimes carrying over $1,000,000 in gold to the U.S. Treasury. There was also worry that the British, who had just strengthened their military presence in the Pacific, might attempt to take possession of California while the United States was preoccupied in the east with the Civil War. Even if Britain did not want California for itself, there was the real concern that they might form an alliance with the Confederacy and that San Francisco was vulnerable to attack from the British Navy.

PARC, GGNRA Confederates in California The U.S. Government was also concerned about Confederates within California causing trouble and threatening the state’s security. At the beginning of the Civil War, many California Democrats, both in the northern and southern parts of the state, supported California’s secession as an independent Pacific Republic. The Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret organization of “Chivs” with many transplanted wealthy Southern members, was particularly powerful in developing plans for California’s secession from the Union. During the war, perhaps twenty percent of California’s population was pro-Confederate. Living mostly in southern California, small groups of pro-Confederates actively tried to rouse anti-Union sentiment, in the hopes of adding gold-rich California to the Confederacy. In order to prevent Confederate privateers (privately-owned vessels granted license to capture enemy shipping) from attacking and robbing ships carrying gold and silver out of the San Francisco Bay, the military Department of the Pacific greatly increased its West Coast troops. The military added 1,700 soldiers in California and 1,900 soldiers in Oregon, equaling nearly a quarter of the United States’ peacetime army. The End of the War As the Civil War lingered on and the Union seemed likely to win, the U.S. Army was willing to devote more resources to the Pacific Coast. The end of the bloodshed came in sight when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865. Unlike the news of the beginning of the war, which took twelve days to reach California on horseback, the news of its end quickly reached San Francisco via telegraph. The city erupted in great celebration, with citizens cheering in the streets and guns booming from many of the forts around the bay. Less than a week later, on April 15th, another telegraph came bringing less joyous news: this telegraph told the city of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. This time the city descended into chaos. Pro-Union mobs ransacked the offices of a local Confederate newpaper and attacked citizens thought to be pro-Confederate. The military ordered artillerymen from Fort Alcatraz into the city to maintain order, prevent rioting, and punish anyone bold enough to rejoice in the tragedy. Confederate sympathizers throughout California who celebrated Lincoln’s death were arrested and imprisoned on Alcatraz. During the city’s official mourning period, Alcatraz’ batteries were given the honor of sending out a half-hourly cannon shot over the bay as a symbol of the nation’s grief.

To learn more about Civil War historical events at other locations in Golden Gate National Recreation Area, please visit these other pages: Civil War at Fort Mason |

Last updated: May 13, 2020