NPS IntroductionHistoric buildings rarely survive generations by accident. Someone made a choice, or in the case of the Douglass Home, a whole lot of women made a whole lot of choices over decades. They choose to save this home for future generations. No one could ever tell the full story including every single person involved, but in this series we will highlight a few of the women who labored to pass our generation the Frederick Douglass Home. As we read their sacrifices to pass this gift to us, what are we hoping will survive for generations after us?Helen Pitts DouglassAn activist prior to their marriage, HELEN PITTS DOUGLASS, second wife of Frederick, was widowed after his 1895 death. According to Mr. Douglass’s will, Cedar Hill – their final home – was to be inherited by Helen Pitts Douglass. An error was found in the will and it was challenged in court. To acquire full rights to the home, she took out a $15,000 mortgage and bought out claims from surviving Douglass family members. She was on a mission to “make [Cedar Hill] a national monument and memorial to the memory of her illustrious husband.” Francis Grimke, a close friend and confidant of both Helen and the late Frederick observed, “Everything connected with Mr. Douglass was precious in her sight. The fact that he was in any way associated with anything put the stamp of sacredness upon it.”The mortgage helped her secure the home in the short term, but she did not have a clear plan about how she would pay it off. The next year, Helen Douglass approached the National Colored Women’s League and the national convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Women -- a precursor to the National Association of Colored Women -- asking for mortgage and preservation help. Some members took a “pilgrimage” to Cedar Hill, and Helen began encouraging others to visit.

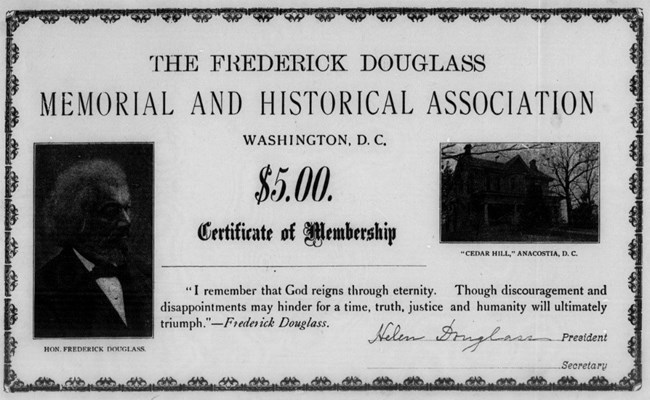

Library of Congress The Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical AssociationBy 1900, Helen’s efforts – with others – led Congress to charter the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association with the purpose of forever preserving the life and legacy of Frederick Douglass. As a part of the newly formed FDMHA, Mrs. Douglass worked hard to pay off the loan. Friends counseled her to slow down, highlighting that memorials to George Washington & Ulysses Grant struggled financially, but “she believed that once the efforts of the FDMHA came to the full attention of Black and other people who appreciated the greatness of Douglass, they would wholeheartedly support the movement to preserve the home.”As the mortgage continued to loom over the organization, a suggestion was made to sell Cedar Hill to create a scholarship fund in the name of Mr. Douglass and herself. She briefly entertained the idea so long as her name was removed, but quickly settled that it was unacceptable the sell the home. It must be preserved! Helen Pitts Douglass passed away December 1, 1903 – eight years after her famous husband. When she passed, a significant amount of the mortgage remained. In her will, Mrs. Douglass left the home, 14.45 acres, and all the contents (except clothing and jewelry) to the FDMHA. Largely powered by the efforts of HELEN PITTS DOUGLASS, preservation was underway. It required others to help.

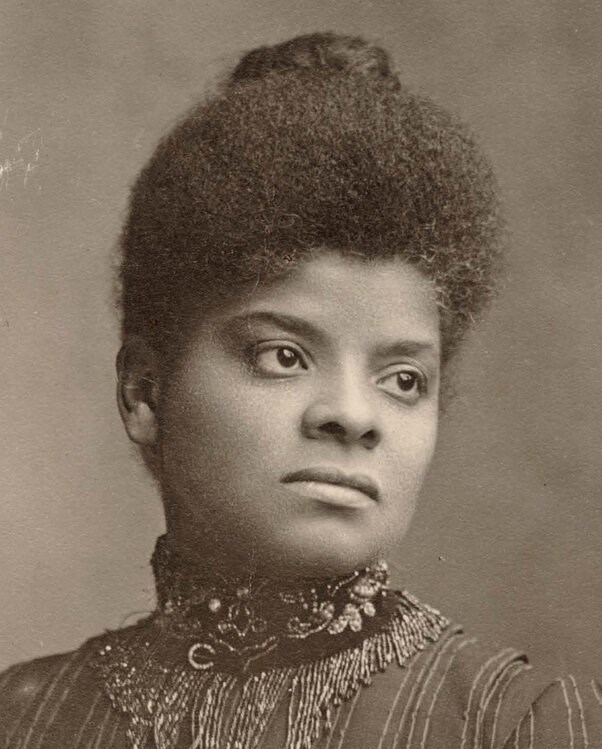

Public Domain Ida B. Wells-BarnettA few years after Mrs. Douglass’s passing, the male-led board of the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association struggled to get the public interested in preserving the home of the Frederick Douglass. In 1912, one of them wrote a newspaper article about the home which was noticed by the powerful leader IDA B. WELLS-BARNETT. The article called for help, “to make of Cedar Hill, a sort of Mt. Vernon for the colored race.” It was hoped to be the center “of the history and achievement of the colored American.” Hearing about the frustrating lack of financial support, Ida B. Wells-Barnett asserted that the trustees responsible for the home had not kept folks properly informed. “What the race does not know,” she replied, “it cannot do.” Highly critical of prominent men like Booker T. Washington, she believed they failed to use their positions and platforms responsibly in this cause. Writing from Chicago, she explained that folks outside of the District of Columbia believed these men had already paid off the remaining mortgage.Correct information was critical, and she believed it was lacking. IDA B. WELLS-BARNETT wondered about how committed these men really were. They had the resources to pay off the mortgage without needing help from the outside. Why didn’t they? Most of the trustees lived in Washington, the same location as the Douglass Home. In her view, if these men lacked the “race pride and patriotism” to save the home, perhaps a different approach was needed where “the race will gladly respond.” In the next few years, the all-male board of trustees overseeing the Douglass Home became an all-female board, working in partnership with women’s organizations.

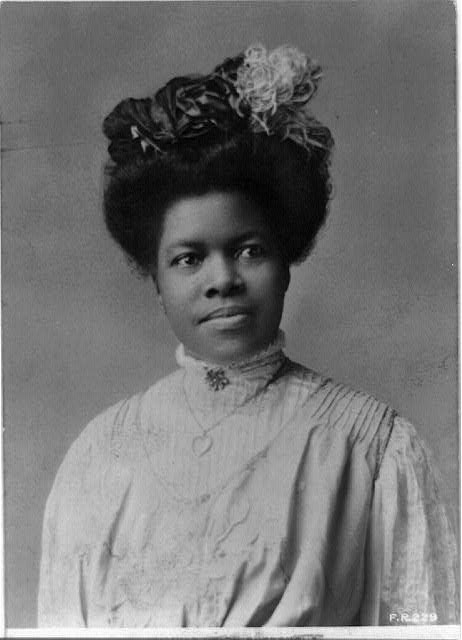

Champion Magazine Mary B. TalbertIn the first years of preservation, the late Helen Douglass and Rosetta Douglass-Sprague had reached out to other organizations for help. By 1916, the Trustees for the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association followed that example and reached out to the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). MARY B. TALBERT served as NACWC President. Under Mrs. Talbert’s leadership, the NACWC filled a majority of FDMHA Trustee seats with Black women from their organization. Mrs. Talbert also led the formation of the NACWC Douglass Home Committee, featuring prominent names like Maggie L. Walker and Nannie Helen Burroughs. These two committees worked together to eliminate the debt and save the Douglass Home.Through her visionary guidance, Talbert called on every clubwoman and child to raise money for the restoration of the home and grounds. Two years later, Mrs. Talbert raised enough and Helen Douglass’s mortgage was paid off. The NACWC celebrated by inviting donor Madam C.J. Walker to burn the mortgage papers in front of a crowd. Mrs. Talbert’s drive continued to raise money to improve the structural condition of the home.

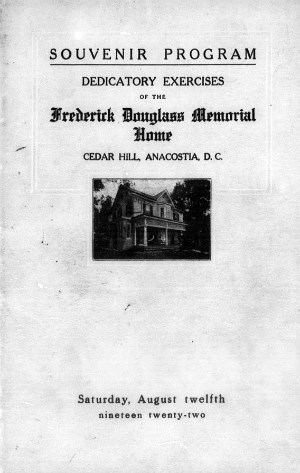

Library of Congress The Frederick Douglass Memorial HomeBy the summer of 1922, the NACWC and FDMHA met publicly for a ceremony at the Douglass Memorial Home. Standing in front of the home, now debt-free through her guidance and the sacrifice of the women of the NACWC and FDMHA, Mary B. Talbert declared, “we can always look up and point with pride to this, the first great race shrine – redeemed by our people, for our people.” President Talbert raised over $11,000 for the care of Cedar Hill.This effort, combined with her many other contributions, made her the first women to receive the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal that same year. As she celebrated the accomplishments of the moment, she acknowledged in August 1922 that more was needed if this success was to continue. MARY B. TALBERT passed away shortly after the celebration at Cedar Hill. Like Helen Douglass before her, she did her part to address the needs of the moment. Was the momentum sustainable? It was up to others now.

Library of Congress Nannie Helen BurroughsDeeply involved in the preservation of the Douglass home under Mary B. Talbert, NANNIE HELEN BURROUGHS was a busy woman. As founder and president of the National Training School for Women and Girls, she called on them for donations to support the preservation of the Douglass Home. A driving force across decades of Cedar Hill’s story, Burroughs – who lived in Washington – was seen by many others as their on-the-ground contact. As the NACWC and FDMHA tried to work together, problems arose and things did not always run smoothly. Miss Burroughs was named “Official Custodian of Buildings and Grounds.” It was her task to see Cedar Hill well-maintained in a time when funds were slowing down and working relationships between organizations began eroding. In addition to her role at the National Training School, Burroughs was in the Women’s Auxiliary of the National Baptist Church, and leading as an organizer and public speaker. Her time was limited, but distant committee members and trustees kept demanding her undivided attention on the Douglass Home. “You are busy,” she was written from Indiana, “so are we.” The women’s groups had brought on a caretaker, Burroughs was made to evict them. A new caretaker was needed, Burroughs did the interviews. When contractors were brought in for work, Burroughs was the on-the-ground person to check in. She was also responsible for paying them but was not regularly sent the necessary funds to do so. It was an important, though unenviable, position.Nannie Helen Burroughs continued caring for the home and grounds into the 1940s. She saw the full breakdown of the working relationship between the NACWC and FDMHA, as well as their periodic re-unifications. She battled on, stating, “we should be willing to do these necessary things to preserve and make more attractive our glorious shrine.” In spite of her best efforts, the funds failed to support her vision. In 1939, she described Cedar Hill in a letter, “I need not tell you that it is filthy because you saw it.” In a scorching 1941 letter to the women, Burroughs called them “not faithful to their trust. The home is in a terrible condition. In fact, it is a disgrace to Negro women…Who is responsible? You. You ran in two years ago, held a brief meeting and left me in charge of buildings and grounds, and did not leave one cent with which to do anything.” She explained how she had to ask others for emergency funds, such as Mary McLeod Bethune. The FDMHA spent all their resources paying back Bethune, while they awaited the NACWC’s promised funding. Burroughs charged that the home was neglected and that the public had right to question “that we know our business.” She closed by telling the Trustees, “if we are honest with ourselves, we will confess we have done a mighty poor job.” When the letter was read at the next NACWC meeting, $1,800 was immediately allocated and sent to the FDMHA. The solution appears to have only been temporary. Into the 1950s, Burroughs continued to communicate “the continuous and gross neglect” of Cedar Hill. As the main person who saw the home and grounds, NANNIE HELEN BURROUGHS had to face the day-to-day impact of the NACWC and FDHMA’s breakdown in cooperation. She knew the Douglass Home deserved better and labored as best she could until Cedar Hill was given the funding stability it desperately needed.

Johnson Publishing Company Mary McLeod BethuneIn the 1920s, the mighty MARY McLEOD BETHUNE was named to the NACWC’s advisory board for the Douglass Home. A little more than a decade later, Bethune was Director of the Division of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, the first Black woman division head in the United States Government. By then, she was also a Trustee for FDMHA and former NACWC President, in addition to her roles as the founder and President of both Bethune-Cookman College and the National Council of Negro Women. A dynamic leader, Mrs. Bethune utilized the National Youth Administration (NYA) to conduct landscaping at Cedar Hill. In 1936, 50 boys were assigned to learn gardening and horticulture in a partnership with Phelps Vocational School. The Douglass Memorial Home was to be their laboratory. The grounds were cleared, slopes re-terraced, new plants and trees added. Even Douglass’s “little den,” or Growlery, received a new roof. Bethune’s influence made tremendous progress.From 1936-1938, Mrs. Bethune had 245 different young men working on the grounds. They “have made a great contribution in preserving and increasing the beauty of the Douglas[s] Memorial Home.” During this same time, she also led the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in conducting a major inventory of the contents of the home, the first since Helen Douglass was alive. To fulfill this request, the caretaker on the grounds, Mrs. Davis, was “searching attic boxes, store-away places and every corner of the mansion to find all valuable manuscripts, books, etc. because she has the services of some white collar workers to assort, assemble, index and file all such materials.” MARY McLEOD BETHUNE made things happen. While competing organizations battled over funds, control, and strong personalities, Bethune not only leveraged the NYA and WPA to get things done, but re-allocated money behind-the-scenes to address emergency roof repairs. She met the moment. As many others recognized, Mrs. Bethune was well aware that “the work which we have accomplished soon needs to be done over again.”

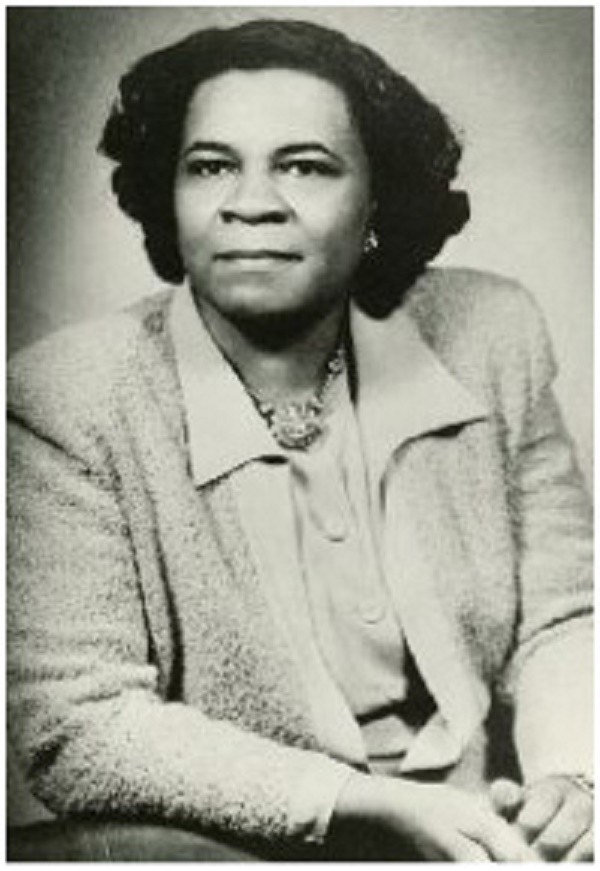

ACPL Genealogy Center Sallie W. StewartSALLIE W. STEWART loved to write. Some thought she wrote too much. As tensions lingered between the FDMHA and NACWC, Nannie Helen Burroughs believed Stewart’s long letters describing the situation were “simply adding fuel to the fire.” Burroughs added, “She writes entirely too much!” As one responsible for coordinating so much of the partnership preserving the Douglass Home, Stewart needed to write, speak, and advocate. She also tried to keep some of the behind-the-scenes drama from spilling into the public. As a FDMHA trustee, she saw a press report blaming the FDMHA for the deteriorating condition of the home. According to the agreement, the FDMHA had title to the home, but the NACWC was supposed to send them the money to take care of it. In Stewart’s observation, the FDMHA could not pay its bills, because the NACWC failed to consistently uphold their part of the agreement. “I do not wish to publish the story as to why we have no funds,” she wrote privately. She called the whole situation a “tie-up” between the two groups. On the occasions where periodic money arrived, she immediately put it to use. She never knew when more would arrive, however. Rather than being able to provide consistent preventive care for the property, she had to use the money where she could, addressing one crisis after another. On multiple occasions the FDMHA nearly emptied their own finances while awaiting the promised help from the NACWC.Hoping to be more self-sufficient, by 1946 Mrs. Stewart – President of the FDMHA – called on all members to talk about the condition of Cedar Hill at every public gathering, and especially pressed Nannie Helen Burroughs to use her large platform to reference the home. She worked considerably with Douglass granddaughter Fredericka on the efforts. She asserted that without the FDMHA “there would be no semblance of the Douglass Home.” Frustrated at the perceived unreliability of the NACWC, Mrs. Stewart launched her own campaign to fund the home for the long-term. Regarding the NACWC’s past contributions, she announced, “it was their own fault if [the NACWC] did not have papers to protect their interest.” After that comment, the next NACWC meeting voted to provide no more funds. Stewart left the meeting, going straight to Douglass Home caretaker Gladys Parham “very upset.” Hoping to ensure permanent financial security, SALLIE W. STEWART agreed to a business arrangement. A portion of the Douglass estate would now house an apartment complex which would generate a consistent revenue that would go to perpetually care for the home and grounds. She made a move to sacrifice some land for total financial stability. Unfortunately for the FDMHA, this move went wrong in many ways, but perhaps not in a way Mrs. Stewart could have anticipated.

Public Domain Fredericka Douglass Sprague PerryA granddaughter of Frederick and Anna Douglass, FREDERICKA DOUGLASS SPRAGUE PERRY, made several donations to the efforts to save her grandparents’ home. She grew increasingly frustrated with the inability of the NACWC and FDMHA to cooperate. “The women care nothing for Frederick Douglass or for what he stood – why deceive ourselves!” As a Trustee for the FDMHA, Fredericka “resent[ed]” that the NACWC “dictate[d]” to the FDMHA. There were calls for the title to be transferred to the NACWC, which she opposed. As a Trustee, she saw it her responsibility to “perfect” the FDMHA, not give up on it. If funds were not coming in as promised, they needed to raise them independently. During the 1940s, she noted that plenty of other causes were raising money during wartime, so there was no excuse they could not succeed. Mrs. Perry worried that failure would “cast great reflection upon the Negro women’s business ability.” They must get it done. In the event they were unsuccessful, she pondered giving it to the government.Fredericka Perry visited the home often. She “spent many cool eves on the hill” with the caretaker, Mrs. Davis, just as she had years before while playing with her loving grandfather. For her, it was not just a historic home of a vital figure in the American story, it was a place of childhood memories and family. She worried about the future, not just of the home, but her grandparents’ belongings inside. In a home filled with family and historic treasures, she noted the value of many items inside. It is remarkable there was never serious discussion about selling Douglass items to pay the bills. FREDERICKA DOUGLASS SPRAGUE PERRY went even further. Instead of proposing to sell artifacts, she wrote, “I have some materials here that was our mothers. Some I will use and some I would like used at Cedar Hill. Time is taking its toll – I would like to do my bit to help the women of the nation in the restoration of this home.”

NPS Gladys B. ParhamIn the 1920s, the partnership between the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association hired caretakers to live on the grounds of the Douglass Home. In 1928, they built a cottage directly behind the home for the caretaker. GLADYS B. PARHAM was hired in 1949. She lived rent free, but in exchange cleaned and safeguarded the property. Mrs. Parham recruited Boy Scout troops, in addition to children from nearby Barry Farms to help with the grounds. She also gave tours of the Douglass Home. Mrs. Parham sacrificed for Cedar Hill. For three years, she went unpaid. While the NACWC and FDMHA squabbled around her, only the light bill could be paid. Everything else had to wait. In spite of her best efforts, she was “greatly disturbed” by the deterioration due to lack of funds. The lack of salary forced her to work another job.Gladys B. Parham ended her membership in the NACWC, instead joining the District Baptist Convention, because they “always knew where the money was going.” As she labored, she was convinced the problems were not due to a lack of money, but rather “improper accounting.” Regardless of what swirled around her, she heroically battled against time and elements to protect the home. Despite her personal opinion on whose fault it was, her commitment during this delicate time was vital in preserving the home in the final years before government involvement.

NPS The Guardian Angel of Cedar HillMrs. Parham estimated she spent about $1,000 of her own money to cover expenses. She commented, “I did not do it for the money.” When the home transitioned into the National Park Service in the 1960s, she continued living in the caretaker’s cottage and was put on the NPS payroll in September 1965. She remained until her passing in 1983, having served the Douglass home for 34 years. GLADYS B. PARHAM joined a chorus of voices who sought the survival of the Douglass Home. She was hired to do a job and did that job even when the hiring groups occasionally failed her. The latest in a long line of women laboring to protect the home, this “Guardian Angel of Cedar Hill” has a plaque on the old caretaker’s cottage acknowledging her pivotal role in fulfilling the dreams of prior generations, and passing them down to future generations.

Public Domain Rosa L. Gragg & Mary E. C. GregoryIn the effort to protect the Douglass property, the NACWC and FDMHA have not always seen eye to eye. Though united in vision, from time to time they struggled to harmonize the details. In the 1960s, the two organizations worked to improve their relationship. Key in this process were NACWC President ROSA L. GRAGG and FDMHA President MARY E.C. GREGORY. Rosa L. Gragg of the NACWC was now given a role at the next FDMHA meeting. Representatives from both organizations met in New York City in 1960. Several board members were removed for “non-cooperation.” President Gragg announced nearly $13,000 for the FDMHA. Things were improving. When it comes to these two women, Gragg and Gregory were described as “equally strong leaders.” All was not perfect, however. “While committed to the same cause…there remained an underlying tension between the two women and the two organizations.” Mary E.C. Gregory maintained her belief that the charter of the FDMHA -- done in Helen Douglass’s day -- meant they had the final say and possessed full clear title.Even as Gregory and Gragg worked together, increasing financial burdens weighed them down. The more time passed, the more critical work the Douglass Home needed. The future expenses were increasing much faster than projected revenue, even in an ideal partnership environment. If the home was to survive into its second century, something more was needed. President Gregory said, “We want the house to be a symbol of the Negro’s contribution to American history. We want the people to come to Washington to visit the Douglass home the way they visit Mt. Vernon or the Custis-Lee Mansion.” What was the best way to ensure that occurred? President Gragg temporarily moved to Washington to aid in a new effort. Several times over the decades, suggestions were made of government involvement. Now Gragg and Gregory became “prime movers” in this effort. If the Douglass Memorial Home was to survive, they needed the help of the Federal Government.

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum For This and Future GenerationsMary E.C. Gregory, unable to be in Washington herself, sent a FDMHA secretary from D.C. – Elizabeth Clark – to represent her. On May 24, 1962, Clark and Gragg testified in governmental hearings about the importance of Frederick Douglass, Cedar Hill, and its significance for future preservation. In September, Public Law 87-633 was approved and the transition of the Douglass Memorial Home from the FDMHA to the Federal Government was underway. A dedication ceremony was held at Cedar Hill in 1964, although even in that moment, there was some lingering frustration that the FDMHA got all the credit for saving the home. It was noted that the history of the NACWC was “deemphasized and even lost as a result.” Although their relationship was not perfect, both the FDMHA & NACWC played crucial roles in saving the home. Both MARY E.C. GREGORY and ROSA L. GRAGG wanted to highlight the role their respective organizations contributed over the years. Though they may have emphasized slightly different versions of the events, they both treasured the Douglass legacy and lead their women in the efforts of preserving it.As the National Park Service stepped in, the Douglass Memorial Home was closed for nearly a decade of desperately overdue structural repairs, before opening to the public on February 14, 1972. The Douglass Home, first constructed in the 1850s, survived and now belonged to the American people. “Whatever the level of involvement [of the NACWC & FDMHA], the successful transfer of the home to the National Park Service meant to all those concerned that the Douglass Home would finally receive sustained financial support and be assured national exposure.” |

Last updated: July 24, 2021