Article

Cultural Heritage Management in Tanzania's Protected Areas: Challenges and Future Prospects

by Audax Z. P. Mabulla and John F. R. Bower

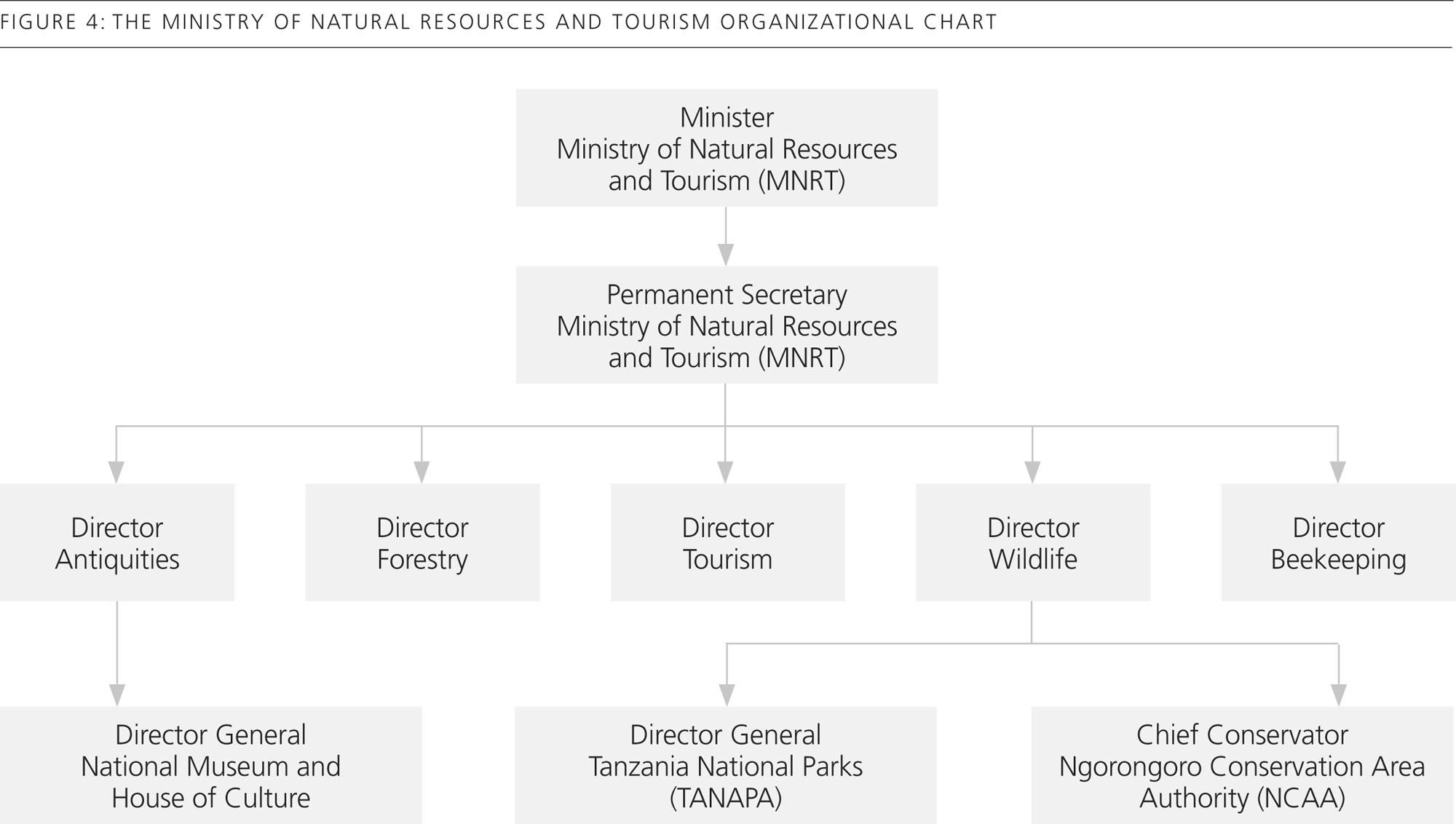

Tanzania is a country of remarkable variety in physical and cultural geography that includes a vast array of natural and cultural heritage resources. (Figure 1) To safeguard its rich and diversified natural heritage, Tanzania has set aside a protected area network covering about 28 percent of the total land area. The network comprises the Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (1 percent), 12 national parks (4 percent), 31 game reserves (15 percent), and 38 game controlled areas (8 percent). Of the protected areas, 19 percent is under wildlife protection, whereby no permanent human settlement is allowed, while the remaining 9 percent consists of areas wherein wildlife coexists with humans.

|

Figure 1. Map of Tanzania Showing Areas with Natural and Cultural Heritage. |

The vast extent of protected areas strongly suggests that a substantial amount of the nation's cultural heritage is located within them. Being located in protected areas should indicate that the cultural heritage resources are relatively undisturbed and safe. However, we observe that cultural heritage resources are seriously endangered in Serengeti National Park (SENAPA) and Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (NCAA). In the next section, we briefly review the natural and cultural heritage resources of these two protected areas and identify some of the recent activities that threaten their survival.

Serengeti and Ngorongoro's Unique Heritage

Natural Heritage

SENAPA is located in three regions, namely, Mara, Mwanza, and Shinyanga regions in northern Tanzania. Established as a national park in 1951, it was designed to promote conservation of wildlife and other natural resources, as well as to advance tourism. SENAPA is the best known, and probably the most important, park in Tanzania. Its main features are its annual migration of large ungulate herds, the sizes of which are unparalleled elsewhere worldwide(1), and its open, rolling grassland plain combined with hilly woodlands. In terms of habitat variation, species diversity, and sheer biomass, SENAPA is one of the great natural wonders of the world.

The NCAA may be viewed as an ecological extension of SENAPA. It is located in the Arusha region in northern Tanzania, and was established in 1959 as a multiple land use area designed to promote tourism and conservation of wildlife and other natural resources, as well as the interests of Indigenous resident pastoral people.(2) The NCAA is unique in the world for its scenic beauty, spectacular wildlife, and important cultural heritage resources. One breathtaking feature of the NCAA is the Ngorongoro Crater, a collapsed caldera of a once massive volcano. The caldera's floor is about 18 kilometers in diameter, forming a circular enclosed plain of about 250 square kilometers.(3) A soda lake and several natural springs and swamps are scattered within. The NCAA also is home to a substantial population of Maasai herders living on traditional cattle and small stock husbandry.

Together, SENAPA and the NCAA support the world's greatest concentration of wildlife, including both herbivore and carnivore species. The NCAA's short grass plains are the wet season grazing and birthing grounds for the majority of the famous Serengeti-Maasai Mara migratory herds of wildebeest, gazelles, and zebra. Because of their rich, diversified natural heritage, UNESCO has inscribed SENAPA and NCAA on the World Heritage List in 1981 and 1979, respectively, under natural criteria. Together, they form the largest biosphere reserve in the world. Due to international recognition of the natural resources they protect, SENAPA and NCAA are one of the most renowned tourist attractions in the world. Moreover, the two areas serve as laboratories wherein scientists conduct research on various aspects of human and wildlife existence in their natural and cultural contexts.

Cultural Heritage

SENAPA and NCAA are also known for their rich and diversified cultural heritage. The Tanzanian government has indicated its intention to re-nominate NCAA to the World Heritage List to consider cultural criteria.(4) Two of the most famous paleoanthropological sites in the world are found within these protected areas. Olduvai Gorge is 100-meters deep and spans 46-kilometers east-west. The exposed two-million-year sediment accumulation within the gorge contains an extensive vertebrate fossil record (including hominids), together with a cultural and paleoclimatic record of central importance to the study of human evolution. More than 60 hominid fossils have been recovered from Olduvai Gorge, so far. These are attributed to Australopithecus (Paranthropus) boisei, Homo habilis, and Homo erectus. The cultural record ranges from stone artifacts of the Oldowan culture, dating to about two million years ago and characterized by choppers and other large core tools, to the small microlithic tools of the Later Stone Age about 45,000 years ago.(5) In fact, Olduvai Gorge is the type-site for the earliest evidence of human technology, the Oldowan stone tool techno-complex.

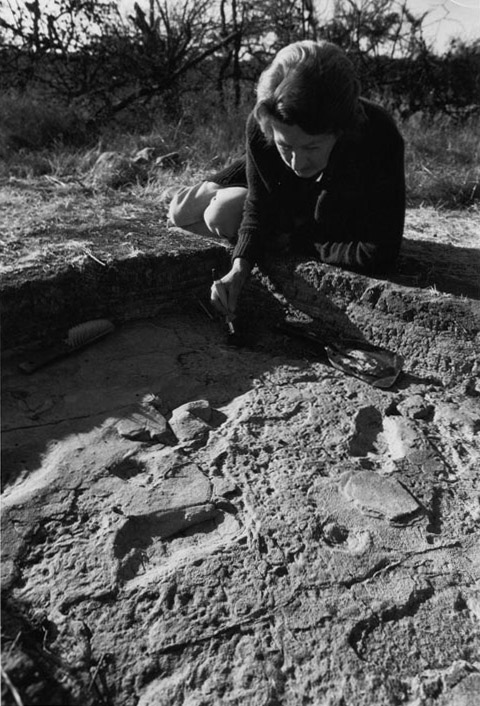

The Plio-Pleistocene site of Laetoli is located 36 kilometers south of Olduvai Gorge in a rolling, open plains setting of the Serengeti ecosystem and may be viewed as contiguous with Olduvai Side Gorge. Laetoli is famous for two remarkable discoveries by the late Mary D. Leakey. First are the over 20 fragments of post-cranial bones, jaws, and teeth of an ape-like human ancestor known as Australopithecus afarensis.(6) Dating to 3.7 million years ago, A. afarensis was, until 1995, our earliest known ancestor. The second important discovery is several trails of footprints made by three A. afarensis individuals, about 3.7 million years ago.(7) The footprints were impressed on a fine-grained volcanic ash and constitute some of the world's strongest evidence regarding the origin of human ability to walk upright bipedaly.(8) (Figures 2, 3) Of course, animal trackways and raindrop imprints are also well preserved in the same horizon. All these discoveries are important landmarks of paleoanthropology.

|

Figure 3. Mary Leakey in front of the Laetoli hominid footprint trail in 1978. (Courtesy of Bob Campbell.) |

Other important cultural heritage resources of later periods in SENAPA and NCAA are stone artifacts of the Middle and Later Stone Age, as well as Pastoral Neolithic traditions; human skeletal remains from various, more recent periods; rock art that includes drawings and engravings; a wide range of wild and domestic faunal remains; and pottery and iron implements. These are known from a handful of locations in the NCAA, including Olduvai Gorge, Laetoli, Nasera rock shelter, and the Ngorongoro crater floor. They have also been found in scattered locations within SENAPA, including excavated sites, such as those at the Loiyangalani River, Seronera Lodge, Gol Kopjes, Sametu Kopjes, as well as numerous surface find spots.(9) The cultural heritage of later prehistoric periods ranges in age from about 200,000 years ago to the present.(10) Contemporary Maasai material culture and indigenous knowledge is also an important dimension of the cultural heritage in these areas. Apart from their scientific value, such resources have high potential to enhance the tourist attraction of SENAPA and NCAA.(11)

Despite the inherent scientific, conservation, and management value of the SENAPA and NCAA cultural heritage resources, they are at greater risk today than at any other time in history. Because of unawareness, misunderstanding, neglect, and management conflicts, the resources are exposed to inadvertent destruction through construction of roads, lodges, airstrips, dams, and other similar land developments. Given the extent of the areas in question, the apparent abundance of cultural resources within them, and the meager research effort that has so far been directed toward their investigation, it seems obvious that such destruction may obliterate a major portion of Tanzania's cultural heritage, severely damaging both paleoanthropological inquiry and the protected areas' tourism potential.

Challenges Facing Cultural Heritage Management in Tanzania's Protected Areas

Cultural heritage management (CHM) is an important public policy issue, both at the international and national levels. At the international level, UNESCO and the World Bank have been the leading agencies in preparing and adopting guidelines on the management of natural and cultural heritage.(12) Among other things, the two international bodies require investors to undertake Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) to ascertain expected impacts on the environment due to socioeconomic developments, and to prevent destruction or damage. Screening for potential impacts on cultural heritage through the Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment (CHIA) is an important part of the assessment, and, if necessary, detailed studies are required to specify negative impacts and prepare mitigation measures.

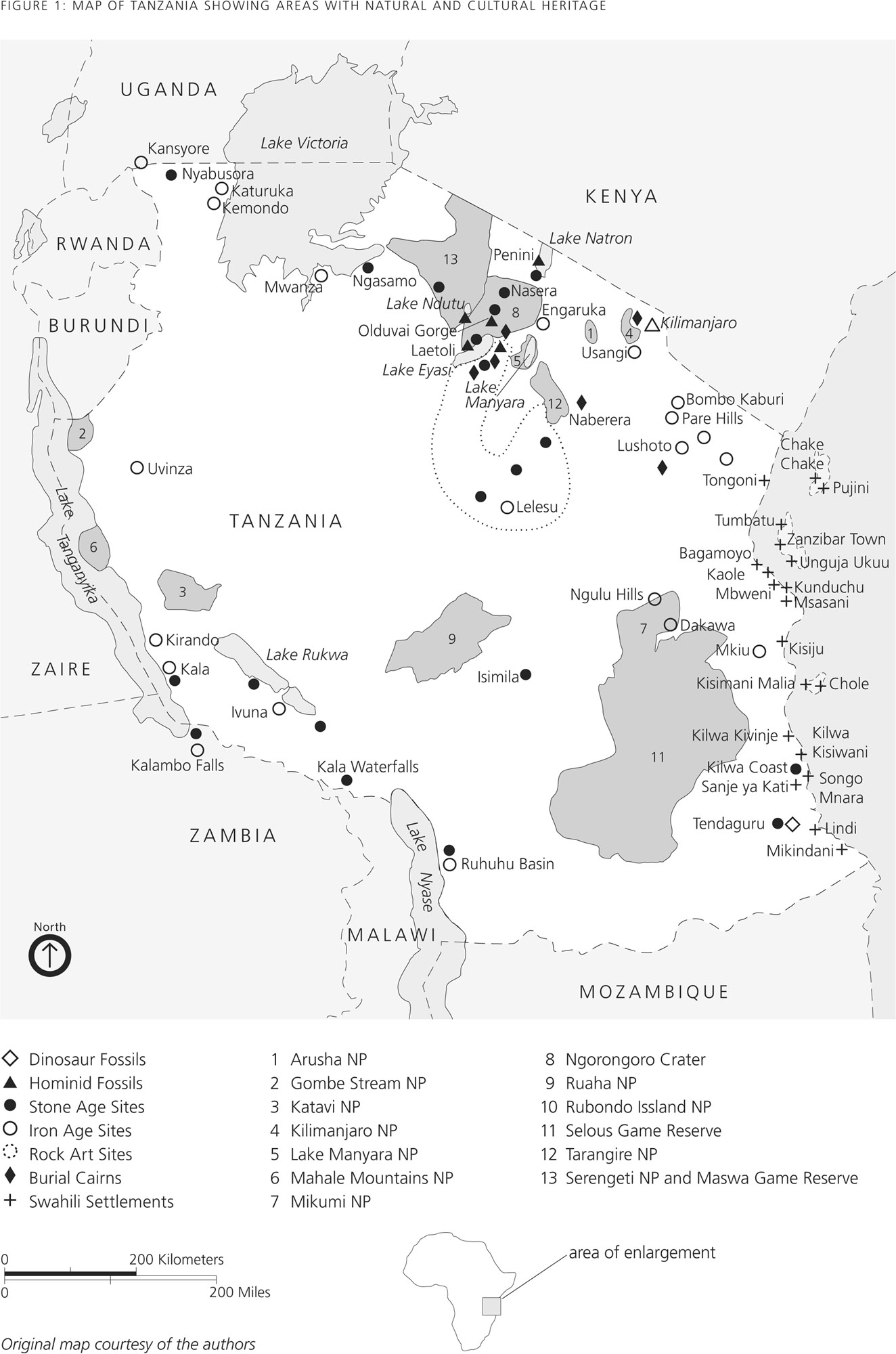

At present, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (MNRT) is responsible for the management and conservation of Tanzania's cultural and natural heritage resources. Within the Ministry, the Director of Antiquities is charged with management and conservation of immovable and movable tangible cultural heritage, while the Director General of the National Museum and House of Culture is responsible for the movable cultural heritage stored in museums. The management of natural resources is the responsibility of the Directors of Forestry, Beekeeping, and Wildlife. The Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA) and NCAA fall under the Director of Wildlife. (Figure 4)

The Antiquities Act of Tanzania, enacted in 1964 (amended in 1979 and 1985), is the basic legislation for the management, protection, and preservation of movable and immovable tangible cultural heritage resources. The act protects all relics that were made, shaped, carved, inscribed, produced, or modified by humans before 1863. Also, the act protects all monuments (buildings, structures, paintings, carvings, and earthworks) made by humans before 1886. In addition, the act protects all objects such as wooden doors or doorframes that were carved before 1940. Under the act, the Minister responsible for antiquities is empowered to declare protected status for any object, structure, or area of cultural value. The act vests the Department of Antiquities ownership of tangible cultural heritage resources. Moreover, the act prohibits the sale, exchange, and export of such cultural heritage resources without a permit. Also, it regulates cultural heritage resources research undertakings. Research on immovable heritage resources is licensed by the Director of Antiquities, while that of movable resources stored in the museum is licensed by both the Director of Antiquities and the Director General of the National Museum and House of Culture. In addition, all management and use of tangible cultural heritage resources are controlled and authorized by the Director of Antiquities. The act forbids activities which might disfigure or destroy cultural heritage resources and imposes sanctions and punishment for offenders in the form of fines, imprisonment or both.(13) Unfortunately, however, the penalty clauses in the current situation are not effective deterrents.

At the national level, the Antiquities Act of 1964 is the principal legislation dealing with cultural heritage resource management in Tanzania. Among other things, the act specifies the need for CHIA. The Director of Antiquities is identified as the act's administrator and therefore is responsible for ensuring such pre-development impact assessments are properly conducted. In addition, the Director of Antiquities should ensure that resources found in an area of impact are scientifically examined, and if necessary, that mitigation measures are undertaken prior to initiation of development work.

Unfortunately, because the process of conducting a CHIA is not explicit in Tanzania's cultural heritage legislation,(14) CHIA is often left out or minimized in EIAs. In recognition of this fact, the newly formulated National Cultural Policy includes a chapter on the conservation and management of the country's cultural heritage resources. This chapter stipulates that cultural impact assessment should be mandatory prior to undertaking development. However, in the recent scramble for development, cultural heritage resources are regarded as low priority, and many new projects continue to be carried out in Tanzania without CHIA. The nation has yet to develop a comprehensive national inventory register of its cultural heritage, and a large part of the heritage remains archeologically terra incognita. Therefore, any activity resulting in disturbance of the land surface is likely to threaten yet unidentified and undocumented cultural heritage properties.

In Tanzania, the national economy substantially depends on heritage-based tourism, especially natural heritage resource tourism. In recent years this economic need has spurred construction of many new lodges and other infrastructure in the national parks. For instance, two upscale lodges have recently been constructed in SENAPA and NCAA, respectively. Unfortunately, no CHIAs were conducted prior to those constructions, despite previous salvage recovery of abundant and varied cultural material during the construction of the Seronera Wildlife Lodge in SENAPA.(15)

Some of the tourist camping sites in SENAPA are located on archeological sites (e.g., the Nguchiro camping site) and vehicle tracks also take a toll on cultural heritage material in protected areas. With increasing numbers of tourist and park vehicles, cultural materials are frequently exposed and trampled along vehicular tracks. For instance, in 2000, one of us (Mabulla) conducted a surface survey along the track from Seronera to the Moru Kopjes. The survey consisted of a linear transect defined by the section of the track that falls between the Seronera and Loiyangalani rivers, a distance of about 20 kilometers. A total of 19 sites were discovered, more or less evenly divided between Middle Stone Age and Later Stone Age occurrences. Vehicular trampling threatens all of these sites, as well as numerous others in SENAPA and the NCAA.

Perhaps the most devastating threat to cultural heritage resources in protected areas is quarrying for road gravels. The problem is widespread. Because park employees are not aware of the rich cultural heritage preserved in their parks, some important archeological sites are being destroyed. One telling example shows the severity of the threat. One of us (Bower) found a rare, well-preserved, and culturally stratified site at the Naabi Hill Gate in SENAPA in 1977. However, when we visited the site in 2000, we found that it had been entirely destroyed by quarrying. In fact, driving on the main tracks in SENAPA, one can observe numerous stone artifacts in the road bed, suggesting that the road gravels are frequently quarried from archeological sites.

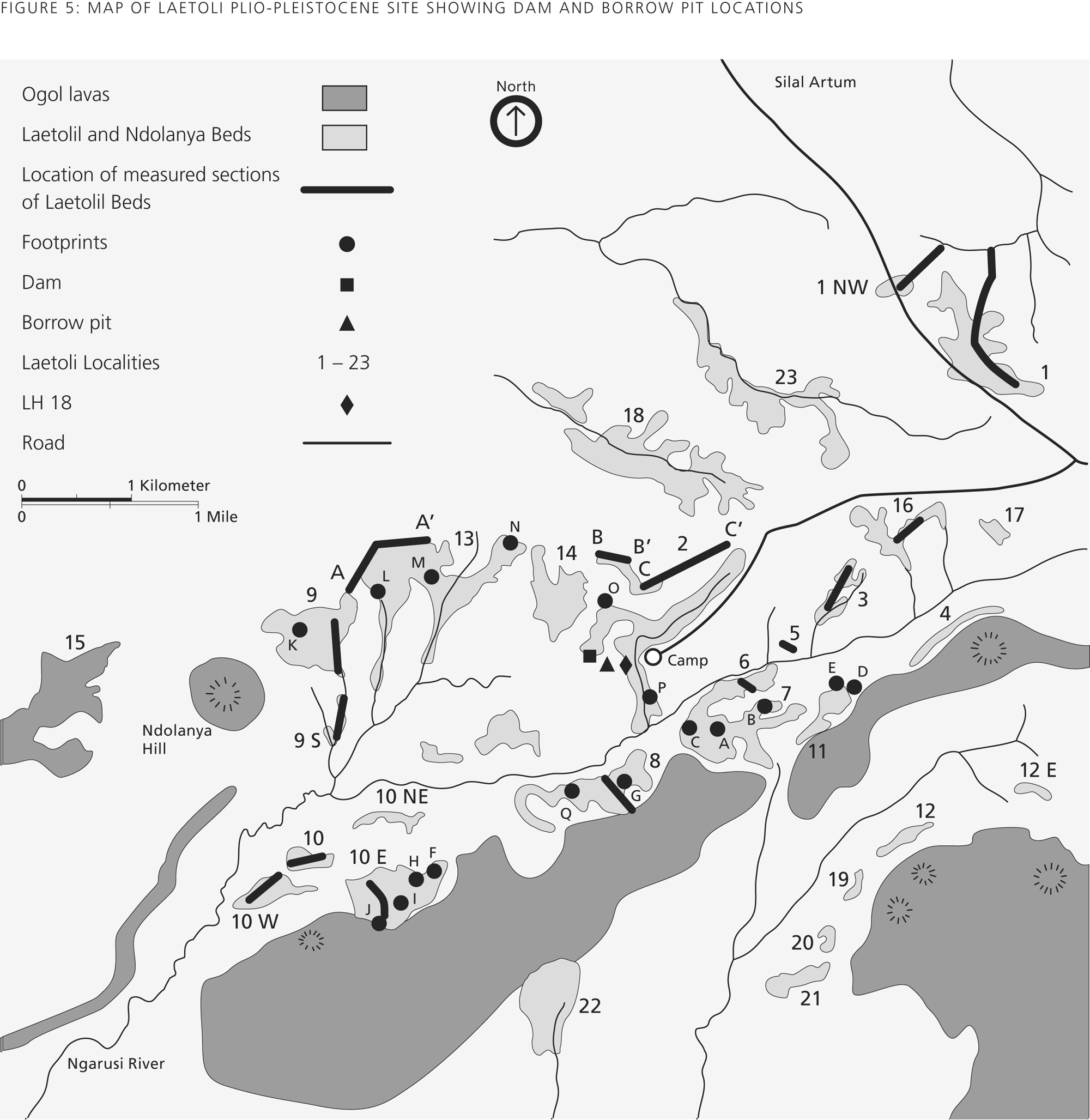

Another cause of cultural heritage destruction in protected areas is the construction of earth dams. Recently, a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), the Ngorongoro Pastoralist Project (NPP-Ereto), built an earth dam in the NCAA. The dam is intended to trap water during the rainy season for use by the local Maasai and their livestock during the dry season. Unfortunately, this dam was built in the Laetoli Plio-Pleistocene site. As a paleoanthropological site, Laetoli is composed of several sediment exposures, known as localities, each of which bears fossils and artifacts. As mentioned earlier, Laetoli is unique in that it contains tracks of hominids and other mammals and birds that are reliably dated to about 3.6 million years ago. The dam was built in 2000 at Locality 2, about two kilometers from the famous hominid trackway that Mary D. Leakey discovered in 1976.

After undergoing a period of neglect, the Laetoli hominid trackway at Locality 8 was recently re-excavated, conserved, and reburied by the Getty Institute of California.(16) In an attempt to increase the local community's awareness of the site, the NCAA and other local officials, school children, teachers, Maasai elders, and the community at large were invited to visit the hominid trackway during the conservation efforts. To reinforce the significance of Laetoli to the community, Maasai elders conducted a traditional ceremony to bless the site. Local guards were hired to look after it and a house was built for them nearby. In addition, monitoring strategies were cooperatively arranged among the local guards, Olduvai Gorge antiquities employees, the Director of Antiquities in Dar es Salaam, and NCAA.

Such efforts are important but they were not enough to ensure the preservation of cultural heritage resources. Despite these efforts, heavy earthmoving machines were brought in and a dam was built in the center of Laetoli. Although one of us (Mabulla) reported the matter to the Director of Antiquities and NCAA, it was, by then, too late as construction was almost complete. Several meetings involving the department of antiquities, NCAA, NPP-Ereto, ward officials, village heads, politicians, the local Maasai and archeologists from Dar es Salaam, were aimed at determining just what went wrong. Both lack of communication and competing priorities between development and preservation were to blame for the situation. Archeologists and antiquities officials' claim that it was a great mistake to build a dam at a unique heritage site was countered by the claim that Laetoli was not as important as the dam. Various officials claimed lack of knowledge either about the site or the location of the dam. In the end, the issue remained unresolved and no one was held responsible for violating antiquities legislation. (Figure 5)

The construction of the dam has wreaked havoc on important cultural heritage resources that could have contributed to our knowledge and understanding of human biological and cultural origins. In an area where water quantity and quality is unpredictable, the dam will attract more people, as well as livestock, to the Laetoli area. Consequently, trampling effects and small-scale farming will increase in an area that is legally protected as a cultural heritage site. Moreover, the flood threat during years of good rainfall cannot be ruled out. As this example dramatically underscores, Tanzania's cultural heritage is at great risk, particularly where it should not be so, that is, in protected areas. In the following sections, we examine the situation in Tanzania in broader perspective, concluding with a remedial agenda for Cultural Heritage Management within Tanzania's protected areas.

Varied Perceptions of Heritage Resources in SENAPA and NCAA

Both SENAPA and NCAA contain rich and diverse natural and cultural resources with outstanding scientific, aesthetic, economic, cultural, and historic importance. Both SENAPA and NCAA are valuable entities, not only to Tanzania and its local communities, but also to the international community.(19) This being the case, the international community (including donors, lobbyists, scientists, and tourists) might be expected to press for conservation and management measures aimed at long-range survival of cultural and physical resources within the heritage sites.(20)

Nationally, Tanzania values SENAPA and NCAA as major earners of foreign exchange through tourism. As a result, conserving physical resources, promoting tourism, and providing and/or encouraging the provision of facilities for the promotion of tourism have been the main functions of both TANAPA and NCAA.(21) After the formation of SENAPA in 1951, legislation was passed that restricted human entry and settlements, and banned traditional hunting, cultivation, and livestock keeping in the park. Consequently, the Masaai people born in SENAPA were moved to the NCAA, which was created in 1959 as a multiple land use area dedicated to the promotion of natural and cultural resource conservation, as well as human development.(22) Today the NCAA is home to about 42,000 Maasai pastoralists. (Traditionally, they are pastoralists, but they also practice small-scale subsistence agriculture to supplement dairy products.) The Maasai people value the NCAA as an irreplaceable grazing resource for their cattle. Furthermore, they are aware of the aesthetic and economic values of the NCAA and have a long-standing attitude of moral responsibility towards NCAA and its wildlife.(23)

Clearly, SENAPA and NCAA are of significance to many different groups. Each of these groups perceives the physical and cultural heritage resources of SENAPA and NCAA differently. As a result, the history of the two areas is a narrative of struggles between groups seeking to pursue subsistence, economic, academic, or leisure interests. Currently, the main competing interests over the use of land in SENAPA and NCAA are between pastoralists on the one hand, and heritage resource managers (including scientific researchers, international donors, and environmental lobbyists) and tourists, on the other. Maasai pastoralists in the NCAA want more land-use rights, greater human and livestock security (including health, education, food, veterinary services, and employment), and water development for livestock and domestic use.

In recent years, water development has been critical to the Maasai of NCAA. When they were moved from SENAPA, the Maasai community was to be compensated in the form of water supply provisions in the NCAA.(24) However, the majority of the water supply systems constructed by the Serengeti Compensation Scheme, and later by NCAA, are non-functional, and those functioning are shared among wildlife, livestock, and humans. Thus, the water system is not only unsafe for humans, but also inadequate to meet the needs of the NCAA's human and livestock populations. In an effort to alleviate this situation, NPP-Ereto has constructed new dams aimed at providing water for both livestock and humans in the NCAA.

Substantially at odds with the indigenous perception of SENAPA and NCAA are the views of heritage resource managers, scientists, conservationists, and the tourism industry. In general, these groups would prefer to minimize the indigenous human presence in favor of wildlife. Particularly influential in this regard is the tourist industry.

Given its ability to generate foreign exchange and employment, tourism is emerging as a new impetus for economic growth in Tanzania.(25) As a result of rapidly increasing investments in the tourist sector and the establishment of government policy initiatives in support of tourism, there has been a dramatic increase in tourist arrivals, from 295,312 in 1995 to 528,807 in 2004, such that the country's target is to attract one million arrivals by 2010. The tourism industry makes a significant contribution to the economy, accounting for nearly 10 percent of national output (GDP) and representing some 40 percent of total foreign exchange earnings from the export of goods and services.(26)

In Tanzania, approximately 60 to 70 percent of tourism is based mainly on wildlife attractions. Activities related to tourism are largely concentrated in the northern wildlife circuit, where the richness and diversity of wildlife, ecology, and landscape, combined with relatively well-developed infrastructures, have led to the establishment of SENAPA and NCAA. But such an accomplishment depends largely on providing facilities that contribute to an outstanding tourist experience. Thus, SENAPA and NCAA each contain at least four upscale tourist lodges and several permanent tented camps, special campsites, and public campsites. These and the game viewing areas are connected by networks of well-maintained gravel roads. Because of the importance of tourism in the national economy, such facilities are often provided at the expense of cultural heritage resources that are destroyed or impaired by construction.

A Global View of Cultural Heritage Management

While the CHM issues we have experienced in Tanzania spring more or less directly from particular circumstances in the areas where we work, they are by no means restricted to that part of the world, having been reported from locations scattered throughout Africa, other Third World regions, and also in highly developed nations. A global perspective on CHM problems can illuminate our concerns, as well as enable our problems to reflect back on the general state of CHM undertakings. In developing a global perspective, we have focused on three broad topics: CHM in relation to development, CHM in protected areas, and CHM infrastructure.

CHM and Development

The current CHIA process, aimed at protecting cultural resources from inadvertent destruction, almost inevitably leads to conflict between economic development projects and the entities concerned with CHM. This is because any agency involved in a development project, whether its role is administrative, political, or commercial, must invest considerable effort and expense in planning a project whose ultimate viability will, in some measure, depend on the outcome of a CHIA study. Thus, without more effective coordination, agents of development are likely to perceive CHM as, at best, a costly nuisance, and at worst, an obstacle in the way of essential economic improvement.

Both cultural heritage managers and developers bear responsibility for resolving conflicts. For example, as MacEachern(27) has indicated, while it may be difficult for archeologists to accept a ranking of sites as part of a CHIA and prioritize conservation efforts accordingly, such an approach may prove essential to the fulfillment of CHM objectives. This consideration needs to be taken into account in any serious effort to resolve Tanzania's CHM issues. On the other side, if developers initiated CHIA early in the planning process, there would be more opportunities for resolving conflicts prior to investing too much time and money into ill-advised projects.

CHM in Protected Areas

Cultural Heritage Management challenges in protected areas, such as certain parks and nature reserves, are largely rooted in the fact that preservation is primarily concerned with natural, rather than cultural, resources. In addition, the preservation effort is often aimed at entertaining tourists to a degree that approaches, or even surpasses, the goal of protecting wildlife. Thus, CHM efforts in protected areas are frequently confronted by a "double whammy" wherein saving animals is given precedence over saving archeological remains, and rampant development of tourist facilities (roads, lodges, viewing areas, etc.) intensifies the destruction of cultural heritage material.

Further complicating the CHM situation within protected areas is the fact that their status as sanctuaries for natural and/or cultural heritage has been challenged by those who argue that the areas should be opened to use by humans who suffer at the expense of wildlife conservation. Such challenges run the gamut from such illegal activities as wildlife poaching,(28) to formal petitions for the removal of protected status. As an example of the latter, Kenya's Amboseli National Park was recently downgraded to a national reserve and turned over to a governing body drawn from the Maasai people, who are the area's pre-colonial inhabitants.(29)

Human occupants, understandably, tend to be primarily interested in their own daily lives and well being. They may be unaware of their living area's protected status or of the preservation rationale that has been applied to the lands in which they live. They may have limited motivation for honoring, much less actively engaging in, the protection of heritage material.(30)

Conflicts arise because various constituents have quite different goals and objectives. Our experience in northern Tanzania's protected areas leads us to the conclusion that each situation presents a more or less unique set of difficulties, such that it is virtually impossible to generalize about coping strategies. However, we can at least isolate one essential ingredient for dealing with the full range of CHM problems in protected areas. We have found that, no matter what specific issues arise, they must be approached with a view toward patient, sometimes painfully tedious, education on both sides of the issue.(31) In other words, we find that resolution of competing claims depends, not only on providing a detailed explanation of the relevant preservation rationale, but also on listening carefully to the objections raised by those who CHM undertakings might affect. In the long run, such education could be enormously facilitated by its extension into adult curricula.(32)

CHM Infrastructure

The effectiveness of any kind of CHM project depends critically on its organizational framework, including research and curatorial staff, facilities, funding, and administration. Unfortunately, there are shortcomings in some, if not all, of these areas throughout the Third World and in many developed countries as well. One of the basic needs in Tanzania is the establishment of a national inventory database of cultural heritage resources.

The most significant problem regarding research and curatorial personnel appears to be a pervasive lack of CHM training. Thus, while African university graduates in archeology are generally competent in field and laboratory research, they are often inadequately trained for CHM work. The obvious solution would be to add a substantial array of CHM coursework and field experience to the university archeology curriculum. Of course, this is much easier to envision than to put into effect, for it entails not only a major curriculum restructuring, but also retraining of faculty and the building of necessary instructional infrastructure, all of which would require large funding increments. The same applies to the (sometimes desperate) need for improved field equipment, research laboratories, and curatorial facilities, whether located in a museum or on a university campus.

Supplying the funds needed to carry out a program of this sort would present many Third World nations with an insurmountable fiscal challenge. However, there is at least a glimmer of hope, thanks to some recent developments in the CHM practices of southern African countries. Among the more encouraging of these is the establishment in South Africa and Botswana of the principle that development projects subject to cultural resource clearance are required to pay for mitigation. It might be possible to dedicate a portion of the proceeds to the enhancement of CHM infrastructure. Along these lines, it is advisable that parks should be required to dedicate a small percentage of their tourist fees to support CHM projects within their borders. Ultimately, of course, any such initiatives will need to be established by governments, a fact which underscores the vital importance of engaging the interest of government agencies and politicians in CHM issues.

Future Prospects of Cultural Heritage Management in Tanzania

We can identify five major categories of need for the proper management of heritage resources. These are: 1) education about cultural heritage throughout Tanzania society, 2) enforcement of laws and improved legislation concerning CHIA, 3) coordination of roles and responsibilities among various constituencies and among natural and cultural resource managers, 4) training for CHM specialists, and 5) research on archeological heritage. Because the kinds of issues we face in Tanzania are evident in various other parts of the world, remedies proposed here may point the way toward improved CHM in other nations.

Education

Like the citizens of many nations, most Tanzanians do not have adequate information about their rich and diversified cultural heritage. Many do not comprehend the immense contribution of Tanzania's cultural heritage to an understanding of human origins and history. Education and outreach programs for both children and adults could help to avoid the inadvertent destruction of cultural heritage in protected areas.

It is important to raise awareness of cultural heritage throughout Tanzania, touching all age groups and community categories.(33) At a glance, this may seem a simple undertaking. In reality, it will be expensive in terms of financial resources and personal commitment of time and energy aimed at eliciting the assumption of responsibility for CHM by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, other government and non-government conservation institutions, and Tanzanian archeologists.

Law Enforcement

Although the cultural heritage is legally protected, the law that requires developers to conduct CHIA has yet to be adequately elaborated. Under the Antiquities Act, a developer who incidentally exposes a cultural resource during development activities is supposed to stop and report the discovery to the Director of Antiquities. The Director of Antiquities is then required to visit the site, evaluate the resource's cultural significance, and make appropriate recommendations. This legal requirement is problematic because developers might either not recognize the resource's cultural value, or not report the evidence to the Director of Antiquities.(34) Without proactive policies and a legal basis for CHIA, rampant development will continue to ravage Tanzania's cultural heritage. Therefore, there is a need to revise the Antiquities Act to include legislation that stipulates mandatory CHIA prior to project implementation and requires developers to meet the costs of such activities.

Coordination

Separate government entities and different statutes manage the cultural and natural heritage resources. The Director of Antiquities, which manages cultural heritage, is a government department, while natural heritage is managed by two separate autonomous state-owned organizations: TANAPA for Game Reserves and National Parks and NCAA for the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA). But TANAPA and NCAA both share responsibilities with the Director of Antiquities for managing cultural heritage in their respective areas. Accordingly, the management in protected areas is complicated by overlapping jurisdictions and inconsistent cooperation among responsible parties. The result of such confusion is illustrated by the construction of a permanent tourist tented camp, in 1993, at the rim of Olduvai's main gorge(35) and its later relocation to the Kelogi Hills. The Kelogi Hills contain rock art and other cultural heritage resources, and are located within a five-kilometer area around Olduvai Gorge, an area that is legally protected because of its cultural importance. Yet, NCAA gave permission to build the camp without authorization from the Director of Antiquities.

In addition, the lack of cooperation and coordination between stakeholders, that is, several government departments and public institutions, on the one hand, and the general public, on the other, result in conflicts and inefficient cultural heritage management. Managing the cultural and natural heritage under one institution(36) with protective legal status would lead to a more effective and streamlined oversight of cultural and natural heritage resources. Including archeology as an integral part of the administration of TANAPA and NCAA at levels ranging from headquarters to field staff would greatly reduce the unintended destruction of cultural heritage and will improve the working relations and cooperation between the Director of Antiquities, NCAA, TANAPA, and cultural heritage researchers and managers. Moreover, it will facilitate efforts to build a national cultural heritage inventory and database.

Coordinating the management plans and legal status of entities that are now separately responsible for natural and cultural heritage would alleviate the current overlapping jurisdictions and poor cooperation between the Director of Antiquities, on the one hand, and TANAPA and NCAA, on the other.

Training

Proper management of cultural heritage resources in protected areas is also hampered by the lack of trained cultural heritage specialists. Neither NCAA nor TANAPA has archeologists on staff to recognize such resources and recommend measures for reducing or eliminating impact during construction and other earthmoving activities.

Improving training for CHM specialists will require universities to establish CHM teaching programs at the certificate and diploma levels for personnel who would fill the CHM positions we are advocating. This type of training will also benefit the personnel who are currently working in the cultural sector, but lack the basic professional and technical skills their duties require, and, at the same time, lack qualifications for university degree courses. Training a cadre of junior staff that in essence deals daily with the activities of CHM would greatly improve the management of cultural heritage in protected areas and Tanzania in general.

Archeological Research

Finally, we wish to stress that the term CHM encompasses a wide range of activities aimed at using cultural heritage resources responsibly so as to ensure not only that they are conserved for future generations, but also understood in depth and applied to contemporary scientific and socioeconomic purposes. This is, after all, a concern related to what has been recognized as one of the basic human rights, our cultural rights.(37) Accordingly, TANAPA and NCAA should encourage archeological research in the parks, controlled areas, and game reserves, and should institutionalize archeology in their scientific planning, development, and management decisions. This approach will not only help prevent park and game personnel's unwitting destruction of cultural heritage in protected areas, but also create opportunities to enhance tourism experiences and improve our understanding of ecosystems within the protected areas.

It is worth emphasizing that virtually the only way to obtain information about the ecological history of protected areas, and hence the natural and cultural processes that continually shape and reshape their constituent ecosystems,is through archeological investigations aimed at recovering data about human activities, climate, and non-human organisms over time spans measured in millennia. Such data should ultimately reveal ecosystem dynamics that unfold over very large time scales and are therefore inaccessible to research focused on the present. Thus, the attempt to manage protected ecosystems with a view toward their long-term well-being depends largely on archeological inquiry.

The long-range survival of Tanzania's cultural heritage depends greatly on implementing the kinds of measures we are recommending, as well as others that may arise from experience with the kinds of CHM programs we are advocating.

About the Authors

Audux Z. P. Mabulla is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam, Archaeology Unit. He may be reached at P.O. Box 35050, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, aumab@udsm.ac.tz. John F. R. Bower is Professor Emeritus, Department of Anthropology, Iowa State University, and Research Associate in Anthropology, University of California, Davis. He may be reached at P.O. Box 72006, Davis, CA 95617, U.S.A., jrfbower@aol.com.

Notes

1. Anthony R. E. Sinclair, "Serengeti past and present," in Serengeti II: Dynamics, Management, and Conservation of an Ecosystem, eds. Anthony R. E. Sinclair and Peter Arcese (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 3-30.

2. NCAA GMP, Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority General Management Plan (NCAA, Ngorongoro, 1996).

3. Katherine M. Homewood and W. A. Rodgers, Maasailand Ecology: Pastoralist Development and Wildlife Conservation in Ngorongoro, Tanzania (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

4. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural And Natural Heritage World Heritage Committee, Thirty-third session Seville, Spain, 22-30 June 2009. State of Conservation of World Heritage properties inscribed on the World Heritage List, Document WHC-09/33.COM/7B.Add, Item 9. Item 7B of the Provisional Agenda available: http://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/1801

5. Richard L. Hay, Geology of the Olduvai Gorge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976); Mary D. Leakey, Olduvai Gorge: Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960-1963 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971); Mary D. Leakey and Derek A. Roe, Olduvai Gorge: Excavations in Beds III, IV, and the Masek Beds, 1968-1971 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). Mary D. Leakey, Richard L. Hay, D. L. Thurber, R. Protsch, and R. Berger, "Stratigraphy, archaeology, and age of the Ndutu and Naisiusiu Beds, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania," World Archaeology 3 (1972): 328-341; Audax Z.P. Mabulla, An archaeological reconnaissance of the Ndutu Beds, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania (M.A. paper, Gainesville: University of Florida, 1990); Paul C. Manega, Geochronology, geochemistry, and isotopic study of the Plio-Pleistocene hominid sites and the Ngorongoro Volcanic Highlands in northern Tanzania (Ph.D. dissertation, Boulder: University of Colorado, 1993).

6. Tim D. White, "New fossil hominids from Laetoli, Tanzania," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 46 (1977): 197-230; Tim D. White, "Additional fossil hominids from Laetoli, Tanzania: 1976-1979 specimens," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 53 (1980): 487-504.

7. R. Drake and G. H. Curtis, "K-Ar geochronology of the Laetoli fossil localities," in Laetoli: a Plio-Pleistocene Site in Northern Tanzania, eds. Mary D. Leakey and John M. Harris (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 48-52; Richard L. Hay, "Geology of the Laetoli area," in Laetoli: a Plio-Pleistocene Site in Northern Tanzania, eds. Mary D. Leakey and John M. Harris (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 23-47; Mary D. Leakey, "Man's oldest footprints at Laetoli," in Karibu Tanzania: A Decade of TTC's Service to Tourists (Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Tourist Corporation, 1983), 7-9.

8. Mary D. Leakey, "The hominid footprints: introduction," in Laetoli: a Plio-Pleistocene Site in Northern Tanzania, eds. Mary D. Leakey and John M. Harris (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 490-496; Louise M. Robbins, "Hominid footprints from site G," in Laetoli: a Plio-Pleistocene Site in Northern Tanzania, eds. Mary D. Leakey and John M. Harris (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 497-502.

9. John R. F. Bower, "Seronera: excavations at a Stone Bowl site in the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania," Azania 8 (1973): 71-104. John R. F. Bower and Tom J. Chadderdon, "Further excavations of Pastoral Neolithic sites in Serengeti," Azania 21 (1986): 129-133; John R. F. Bower and P. Gogan-Porter, Prehistoric cultures of the Serengeti National Park, Iowa State University Papers in Anthropology 3 (Ames: Iowa State University, 1981); Michael H. Day and C. Magori, "A new hominid fossil skull (L.H. 18) from the Ngaloba Beds, Laetoli, northern Tanzania," Nature 284 (1980): 55-56; John W. Harris and G. H. Harris, "A Note on the Archaeology of Laetoli," Nyame Akuma 18 (1981): 18-21; Mary D. Leakey, Richard L. Hay, D. L. Thurber, R. Protsch, and R. Berger, "Stratigraphy, archaeology, and age of the Ndutu and Naisiusiu Beds, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania," World Archaeology 3 (1972): 328-341; Audax Z. P. Mabulla, An archaeological reconnaissance of the Ndutu Beds, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania (M.A. paper, Gainesville: University of Florida, 1990); J. M. Mehlman, Later Quaternary Archaeology Sequences in Northern Tanzania (Ph.D. dissertation, Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois, 1989).

10. Paul C. Manega, Geochronology, geochemistry, and isotopic study of the Plio-Pleistocene hominid sites and the Ngorongoro Volcanic Highlands in northern Tanzania (Ph.D. dissertation, Boulder: University of Colorado, 1993).

11. Audax Z. P. Mabulla, "Strategy for Cultural Heritage Management (CHM) in Africa: A Case Study," African Archaeological Review 17 (4) (2000): 211-233; Charles Musiba and Audax Mabulla, "Politics, Cattle, and Conservation: Ngorongoro Crater at a Crossroads," in East African Archaeology: Foragers, Potters, Smiths, and Traders, eds. Chapurukha M. Kusimba and Sibel B. Kusimba (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2003), 133-148.

12. Ismail Serageldin and June Taboroff, "Culture and Development in Africa," in Proceedings of the International Conference held at the World Bank, Washington, DC, April 2-3, 1992, eds. Ismail Serageldin and June Taboroff, No. 1. (Washington, D. C.: World Bank, 1994).

13. Donatius Kamamba, "Conservation and management of immovable heritage in Tanzania," in Salvaging Tanzania's Cultural Heritage, eds. B. P. Mapunda and P. Mswema (Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press, 2005), 262-278.

14. A. A. Mturi, 2005. "State of Rescue Archaeology in Tanzania," in Salvaging Tanzania's Cultural Heritage, eds. B. B. Mapunda, and P. Msemwa (Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press, 2005), 293-310.

15. John R. F. Bower, "Seronera: excavations at a Stone Bowl site in the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania," Azania 8 (1973): 71-104.

16. Neville Agnew and Martha Demas, "Preserving the Laetoli Footprints," Scientific American 279 (3) (Sept. 1998): 44-45.

17. Paul C. Manega, Geochronology, geochemistry, and isotopic study of the Plio-Pleistocene hominid sites and the Ngorongoro Volcanic Highlands in northern Tanzania (Ph.D. dissertation, Boulder: University of Colorado, 1993).

18. Michael H. Day and C. Magori, "A new hominid fossil skull (L.H. 18) from the Ngaloba Beds, Laetoli, northern Tanzania," Nature 284 (1980): 55-56; John W. Harris and G. H. Harris, "A Note on the Archaeology of Laetoli," Nyame Akuma 18 (1981): 18-21.

19. Katherine M. Homewood and W. A. Rodgers, Maasailand Ecology: Pastoralist Development and Wildlife Conservation in Ngorongoro, Tanzania (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

20. Issa G. Shivji and Wilbert B. Kapinga, Maasai Rights in Ngorongoro, Tanzania (Nottingham: Russell Press, 1998).

21. SENAPA GMP, Serengeti National Park General Management Plan, 2006-2016 (Frankfurt Zoological Society Africa Regional Office, Serengeti, 2005); NCAA GMP, Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority General Management Plan (NCAA, Ngorongoro, 1996).

22. Scott Perkin, "Multiple land use in the Serengeti region: The Ngorongoro Conservation Area," in Serengeti II: Dynamics, Management, and Conservation of an Ecosystem, eds. Anthony R. E. Sinclair and Peter Arcese (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 571-587.

23. Katherine M. Homewood and W. A. Rodgers, Maasailand Ecology: Pastoralist Development and Wildlife Conservation in Ngorongoro, Tanzania (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

24. Issa G. Shivji and Wilbbert B. Kapinga, Maasai Rights in Ngorongoro, Tanzania (Nottingham: Russell Press, 1998).

25. Josaphat Kweka, Oliver Morrissey, and Adam Blake, "Is tourism a key sector in Tanzania? Input-output analysis of income, employment and tax revenue" (Nottingham: University of Nottingham, 2007), www.nottingham.ac.uk/ttri/pdf/2001_1.pdf.

26. Tanzania, The Integrated Tourism Master Plan for Tanzania: Strategy and Action Plan Update – Final Report (Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, 2002).

27. Scott MacEachern, "Cultural resource management and Africanist archaeology," Antiquity 75 (2001): 866-871.

28. Julie K. Young, Leah R. Gerber, and Caterina d'Agrosa, "Wildlife population increases in Serengeti National Park," Science 315 (2007): 1790-1791.

29. David Quammen, "An endangered idea," National Geographic 210 (4) (2006): 62-67.

30. A. A. Mturi, "Whose cultural heritage? Conflicts and contradictions in the conservation of historic structures, towns, and rock art in Tanzania," in Plundering Africa's Past, eds. Peter Schmidt and Roderick J. McIntosh (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 170-190.

31. John R. F. Bower and Audax Z. P. Mabulla, "Cultural heritage management in the Serengeti National Park (Tanzania): From conflict to cooperation," Paper delivered at the 65th annual meeting of the Society for Applied Anthropology, 2005.

32. M. Poznansky, "Coping with the collapse in the 1990s: West African Museums, universities and national patrimonies," in Plundering Africa's Past, eds. Peter R. Schmidt and Roderick J. McIntosh (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 143-163.

33. Jonathan N. Karoma, "The deterioration and destruction of archaeological and historical sites in Tanzania," in Plundering Africa's Past, eds. Peter R. Schmidt and Roderick J. McIntosh (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 191-200; Audax Z. P. Mabulla, "Tanzania's endangered heritage: a call for a protection program," African Archaeological Review 13(3) (1996): 197-214; B. B. Mapunda, "Destruction of archaeological heritage in Tanzania: the cost of ignorance," in Trade in Illicit Antiquities: the Destruction of the World's Archaeological Heritage, eds. Neil Brodie, Jennifer Doole, and Colin Renfrew (Cambridge: McDonald Institute Monographs, 2001), 47-56.

34. A. A. Mturi, "State of Rescue Archaeology in Tanzania," in Salvaging Tanzania's Cultural Heritage, eds. B. B. Mapunda and P. Msemwa (Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press, 2005), 293-310. Ndamwesiga J. Karoma, "Cultural policy and its reflection on heritage management in Tanzania," in Salvaging Tanzania's Cultural Heritage, eds. B. B. Mapunda and P. Msemwa (Dar es Salaam: Dar es Salaam University Press, 2005), 311-316.

35. Charles Musiba and Audax Mabulla, "Politics, Cattle, and Conservation: Ngorongoro Crater at a Crossroads," in East African Archaeology: Foragers, Potters, Smiths, and Traders, eds. C. M. Kusimba and S. B. Kusimba (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2003), 133-148.

36. B. Kibonde, "The needs for a National Heritage Bureau and a National Heritage Coordination Committee for the Management of Heritage in Tanzania," Paper presented at UNESCO Workshop on The World Heritage Convention, Golden Tulip Hotel, Dar es Salaam, March 26, 2002.

37. Peter R. Schmidt, "The human right to a cultural heritage: African applications," in Plundering Africa's Past, eds. Peter R. Schmidt and Roderick J. McIntosh (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 18-28.