Exhibit Review

Gateway to Gold Mountain: The Angel Island Experience; Tin See Do: The Angel Island Experience; made in the usa: Angel Island Shhh; and My Mother's Baggage: Paper Sister/Paper Aunt/Paper Wife

The Ellis Island Immigration Museum, New York, NY. Curator: Judy Giuriceo

March 8-May 31, 2003

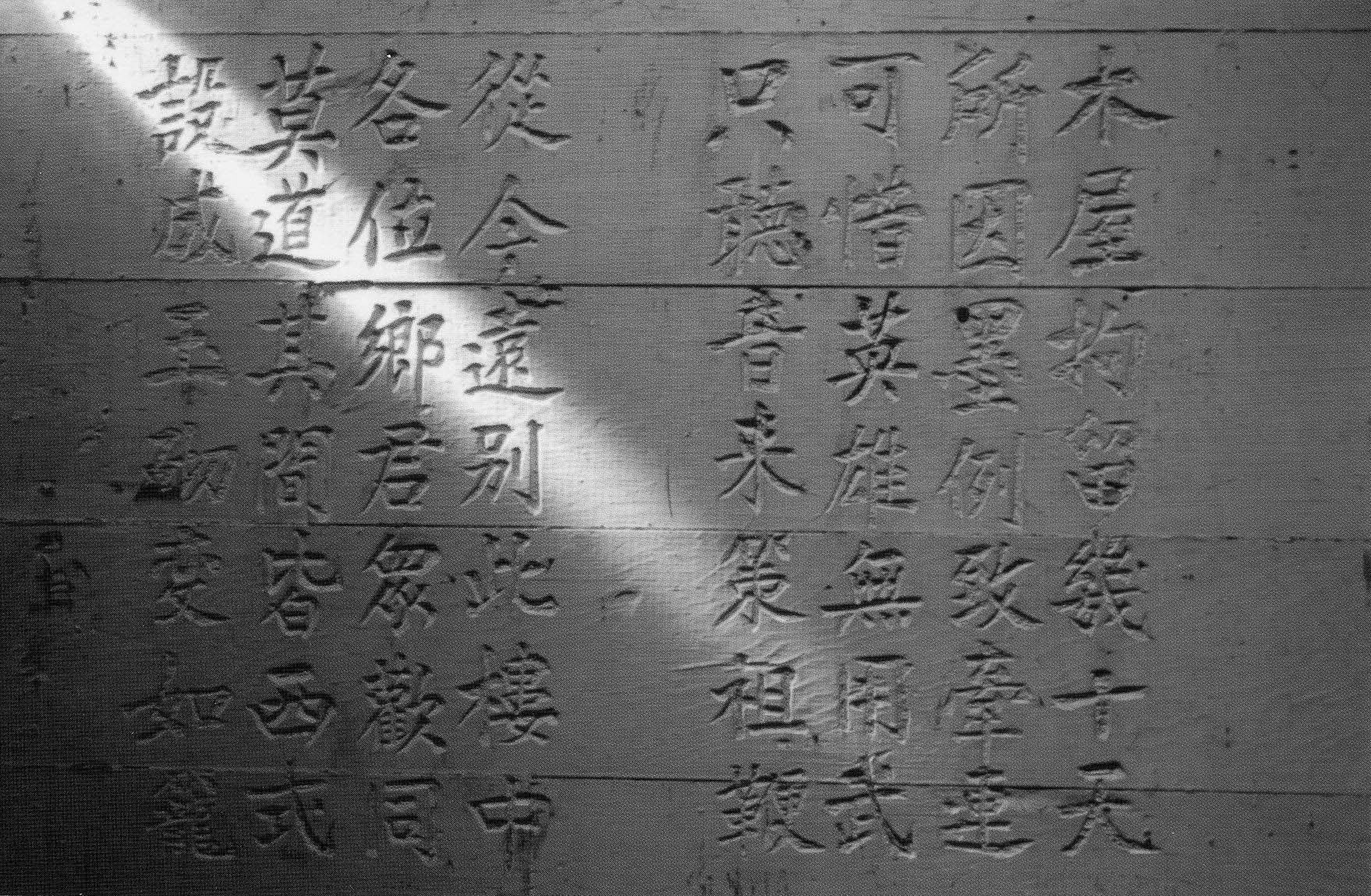

Imprisoned in the wooden building day after day, I look to see who is happy but they only sit quietly. I am anxious and depressed and cannot fall asleep. Nights are long and the pillow cold; who can pity my loneliness? After experiencing such loneliness and sorrow, — From the walls of Angel Island Immigration Station, author unknown |

On a typical daily trip into Manhattan, commuters catching a glimpse of the Statue of Liberty may be reminded of the significance of immigration to the United States. Is there a comparable symbol of immigration on the West Coast? A special exhibit at the museum on Ellis Island reveals its western counterpart, Angel Island Immigration Station.

The Ellis Island Immigration Museum took a novel approach in addressing west coast immigration by combining the Angel Island Immigration Foundation traveling exhibit, Gateway to Gold Mountain: The Angel Island Experience, the Kearny Street Workshop's, Tin See Do: The Angel Island Experience, and installations by artist Flo Oy Wong, made in the usa: Angel Island Shhh and My Mother's Baggage: Paper Sister/Paper Aunt/Paper Wife. Gateway to Gold Mountain and Tin See Do chronicle the journey of Chinese immigrants and their lives during detention on Angel Island. Made in the usa and My Mother's Baggage explore the personal identities of Chinese immigrants. The collaboration among Ellis Island National Monument, Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, Kearney Street Workshop, and Ms. Wong provides a fuller view of the immigration phenomenon.

|

The poetry carved into the walls of Angel Island Immigration Station spoke of the sadness and loneliness of confinement. (Courtesy of Surrey Blackburn.) |

|

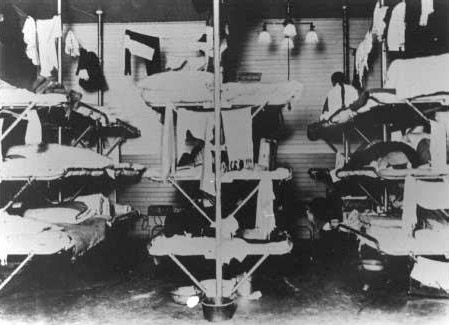

Immigrants stayed in these barracks anywhere from a few days to 2 years. (Courtesy of the California State Department of Parks and Recreation.) |

Angel Island, a State park in the middle of San Francisco Bay, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1997 and, unfortunately, was listed as one of America's 11 Most Endangered Places in 1999 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Between 1910 and 1940, over 1 million people passed through the station. The vast majority were Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, and Asian Indian, with Portuguese, Mexican, and Russian immigrants as well. The significance of the Angel Island experience begins with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first time immigration control was based on nationality or race. Designed to curtail Chinese immigration, the law allowed for additional discriminatory laws directed at other people of Asian origin or descent.

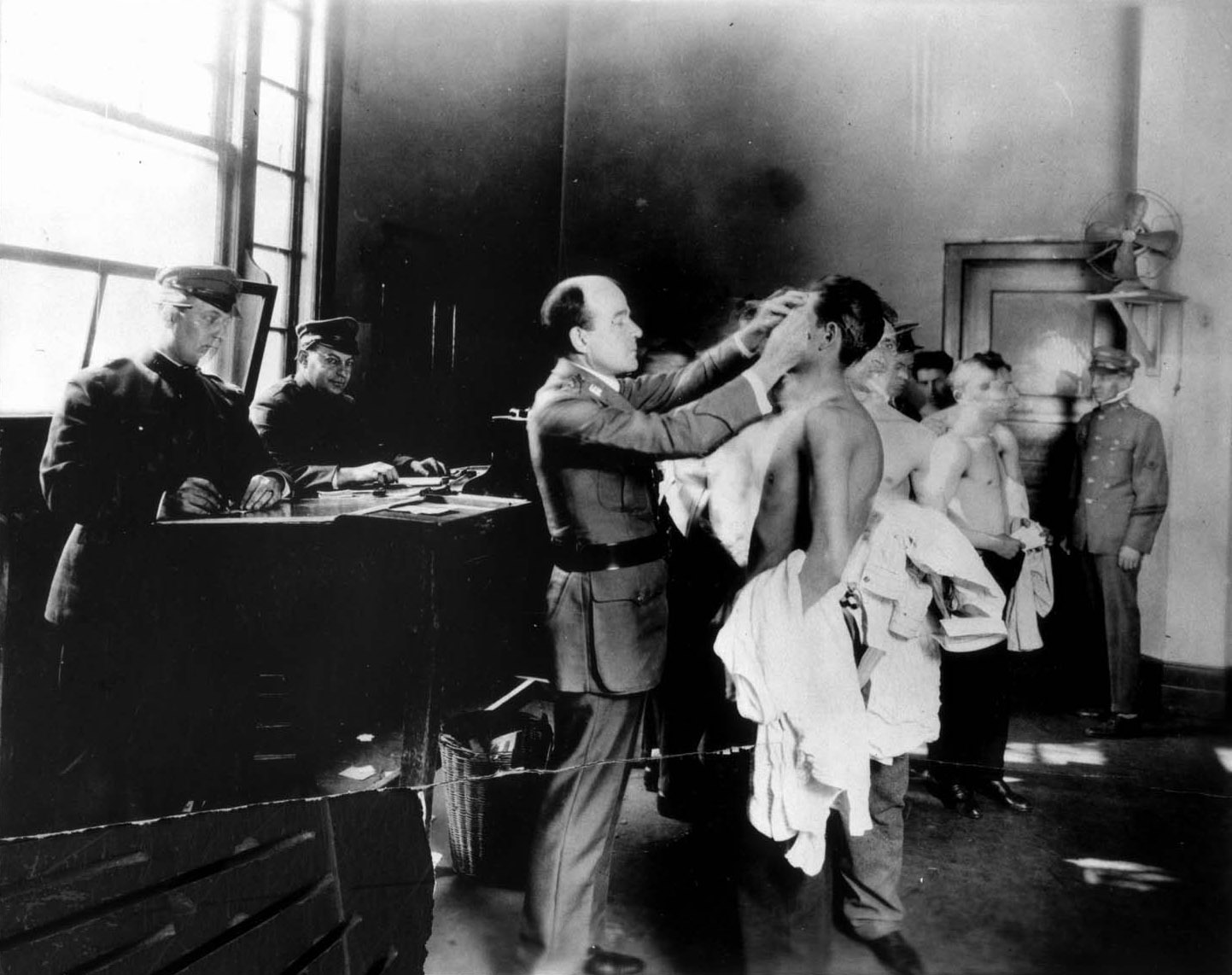

Gateway to Gold Mountain and Tin See Do reveal both the similarities and differences experienced by Chinese immigrants in their pursuit of freedom. Their feelings of sadness and isolation are embodied in the presentations. Most Asians were detained for prolonged periods on the island, from a few weeks to 2 years. The displays depict the attitudes, hopes, and fears of immigrants through photographic images and poetry carved on the walls during their time at Angel Island. Each image or poem reveals the detainees' anxiety, depression, and longing. The photographs vividly capture views of medical inspections and interrogations. The exhibition also includes a video, "Carved in Silence," by Felecia Lowe.

|

Detainees were questioned about their families and what they intended to do in the United States. (Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.) |

|

A doctor examines a detainee at Angel Island. (Courtesy of the California State Department of Parks and Recreation.)

|

The artist's two exhibits, made in the usa: Angel Island Shhh and My Mother's Baggage: Paper Sister/Paper Aunt/Paper Wife, add personal narrative to this history. They feature people, their collected memories, and some historical interpretation by Flo Oy Wong. Both installations recognize the importance of personal stories and oral history as a counterpoint to the photographic records of Gateway to Gold Mountain and i.

In made in the usa, Wong presents the American flag on cloth rice sacks in an ironic play on the symbolism of the flag—freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. She combines the rice-sack flags with photographs and passages from recorded interviews with former detainees to create 25 mixed-media collages of the Angel Island experience. The collages commemorate the trials and tribulations of the detainees' lives. They are markers, moving epitaphs of American history, documented from the spoken word.

Wong uses her family in further scrutinizing immigration. My Mother's Baggage examines the boundaries of truth, and issues of self, identity, and trust, while exposing some of her family secrets. Like other Chinese immigrants, Wong's family came to the United States seeking a better life. Wong's use of suitcases as containers of memories to capture the hidden stories and lives of her family is an imaginative means of demonstrating these private aspects of the immigration process.

The exhibits bring the story of Asian immigration, and in particular Chinese immigration, to a larger audience. It links two major points of entry for the United States, and illuminates hardships associated with the immigration experience that were previously unrecognized. The exhibits accomplish this through an honest and personal inspection of public policy and process.

Atim Oton

A2EO Media, New York