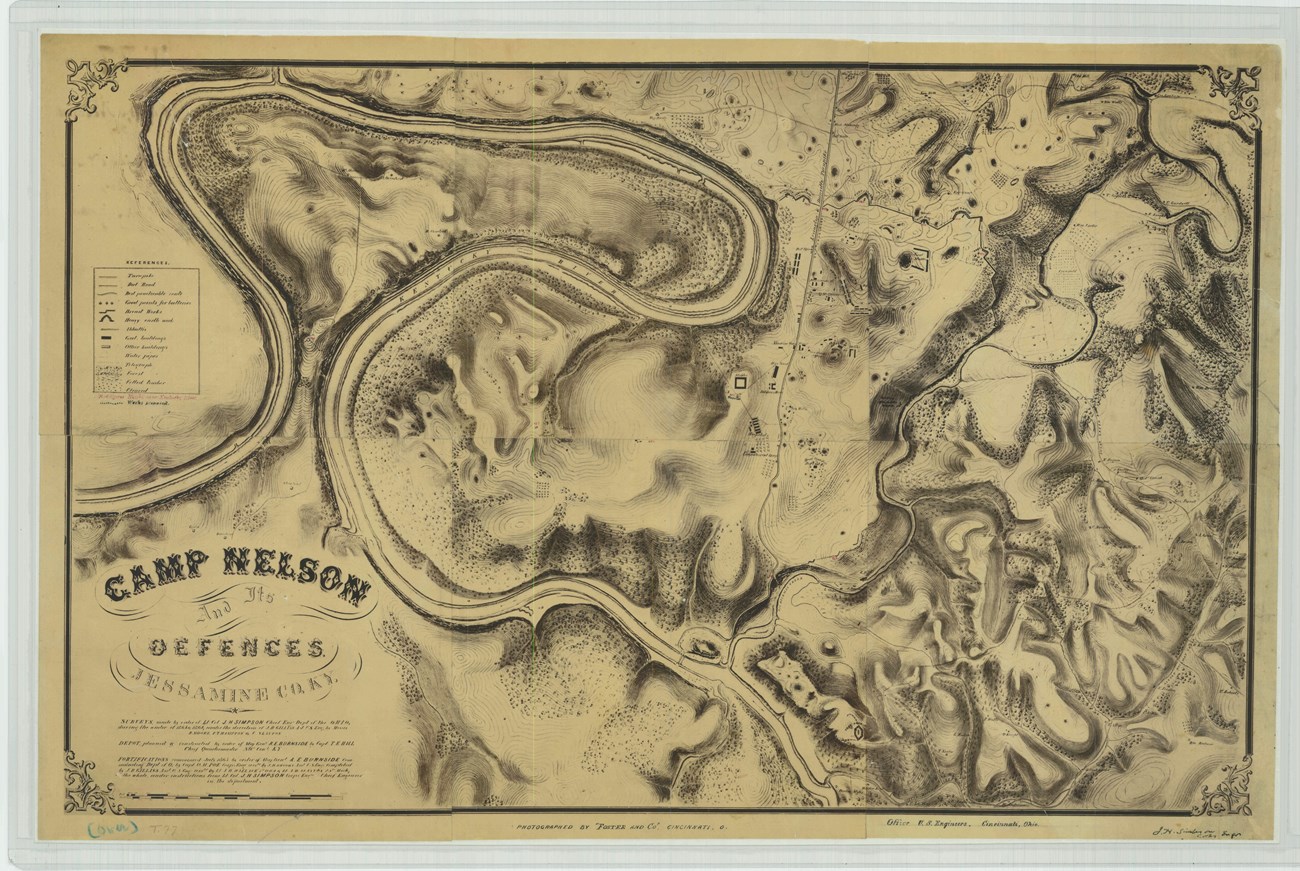

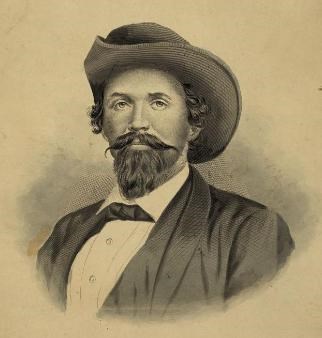

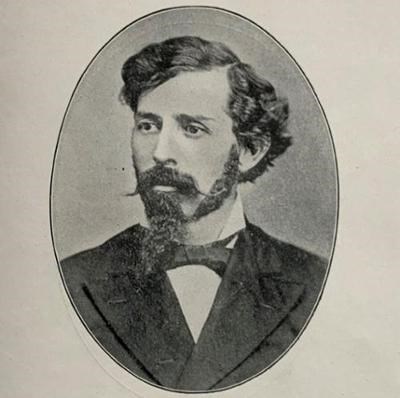

Library of Congress The Morgan Scare at Camp Nelson – June 9-13, 1864In mid-1864, around 3,000 Confederate troopers led by General John Hunt Morgan launched a daring raid through Eastern and Central Kentucky. After gathering his men in southwestern Virginia, Morgan moved his command toward Mount Sterling, where on June 8, they fought a small force of US soldiers and captured the town and its supplies. Morgan’s force then advanced on Lexington, which they seized briefly on June 9-10. Afterward, Morgan’s unruly command rode toward Cynthiana, where over the course of a two-day battle, it was defeated by US forces under the command of Brigadier General Stephen Burbridge, commanding the District of Kentucky. With his raid thwarted, Morgan and his splintered command rushed out of the state and back into Virginia.

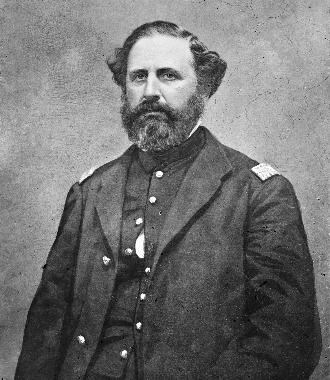

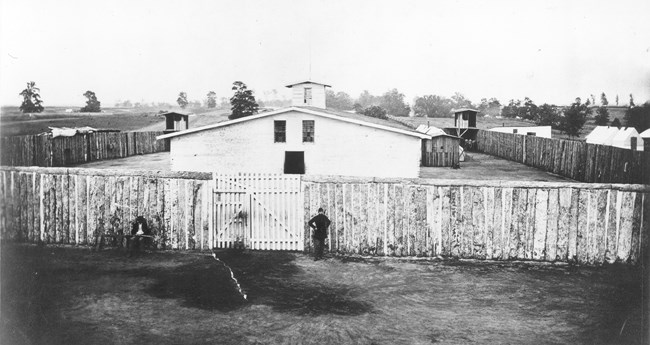

Library of Congress June 9Early on the morning of June 9, US scouts reported that elements of Morgan’s raiding force were ten miles away from Camp Nelson and stealing horses. Unsure of their destination, Captain John B. Dickson, Assistant Adjutant-General, sent a flurry of messages from Lexington to Camp Nelson, which was commanded by Brigadier General Speed S. Fry, informing him of the possible threat. At that time, the base was defended by the 30th Kentucky and 47th Kentucky Infantries, as well as roughly 600-800 formally enslaved African Americans who were recruits for several still-organizing USCT regiments. There were also approximately 500-600 White civilian and military employees who worked at Camp Nelson’s various supply facilities. Even while I am writing, an orderly has come in who reports that the telegraph wires have been cut between here and Nicholasville…No mail has come in or gone out for some days, and we have had no news but what scouts bring in from different directions.

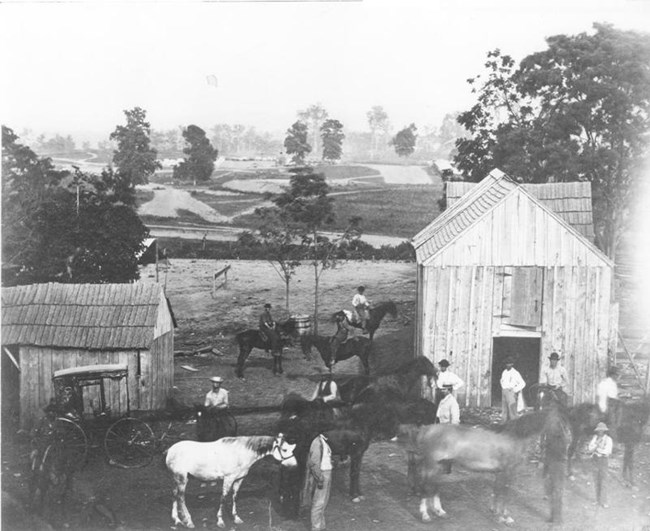

National Archives and Records Administration June 10After Lexington was occupied briefly by Morgan’s column, the Confederates moved further north toward Cynthiana. Leading US officers in Central Kentucky quickly prepared to pursue, ordering all available forces in the area to be equipped and mounted. It was during this urgency to catch Morgan that Camp Nelson’s defenses were stripped. Both the 30th and 47th Kentucky Infantries were mounted, armed, and rushed toward Lexington, where they joined the growing pursuit force. Furthermore, most soldiers being rushed toward Lexington were also armed and remounted at Camp Nelson but not ordered to defend it.

Library of Congress June 11The following morning on June 11, the atmosphere grew even more serious. With the telegraph lines being down, Fry and Clark were forced to rely on news from curriers sent from Lexington and Paris to learn about the developing situation. The news that Fry received throughout that day was grim. A detachment of US forces was surrounded and captured near Cynthiana, which was reached by Morgan’s column that morning. Furthermore, a small contingent from Morgan’s command broke off and attacked the Kentucky capital at Frankfort. Sanitation Commission worker Christopher wrote on June 11: Morgan was at Lexington yesterday...While I was at the hospital, news came that every man able to carry a musket must proceed forth with to the fortifications until further orders. There is a great scarcity of white men in camp now, and rebels no doubt are aware of this. Some of the officers are fearful that if attack should be made there is not sufficient force to resist them: we however will hope for the best. By the afternoon, Fry received a message from General Burbridge ordering him to arm every man in Camp Nelson and use them to defend the base. Fry responded by explaining that every man he had was being used to hold the fortifications. Fry requested reinforcements, but none could be sent because of the scramble to catch Morgan. With no help coming, Fry kept his small force of White employees along the entrenchments awaiting further developments.

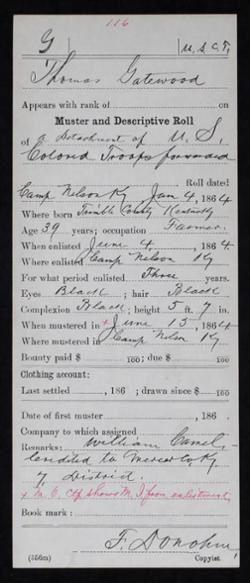

National Archives and Records Administration June 12“Information has been received that leaves no doubt but that the rebels intended to attack the camp,” Major Edgerly was informed on June 12, “You will get out the negro brigade: let them arm themselves with clubs from the woodpile and be ready at a moment's warning to go into the rifle pits.” With an enemy attack seeming more likely, the African American recruits at Camp Nelson were finally given the chance to prove themselves as soldiers. Edgerly was ordered to prepare the USCT volunteers to hold the fortifications that stretched across the northern side of the depot. Some of the recruits potentially manned the various artillery pieces in the base’s defensive forts, but because of the scarcity of small arms, most of the formally enslaved men lacked weapons and had to make do with wooden clubs. On the 23rd of May, 1864, about two hundred and fifty able-bodied and fine looking men assembled from Boyle count, Ky., at the office of the Deputy Provost Marshal, all thirsting for freedom. When this body of colored recruits started from Danville for Camp Nelson, some of the citizens and students of that educational and moral center assailed them with stones and the contents of their revolvers. On their arrival at Camp Nelson, they created great excitement, for they were the first body of recruits that had yet come forward. Reporting to Colonel A. H. Clarke, Commandant of the Post, he refused to accept them, stating that he had no authority for doing so. Although eventually allowed into Camp Nelson, the bloodied party was barred from gaining shelter in the numerous vacant hospital tents at the base and were sent to the “Soldiers Home,” where the Sanitary Commission workers gave them medical care and food. Over the next several weeks, numbers of USCT volunteers made their way to Camp Nelson. But by late May, the only military training the recruits had received came from non-commissioned officers at the base who drilled the men in small squads and platoons. About this time, fears were entertained that John Morgan, the notorious rebel leader, would attack Camp Nelson, as he was then at Lexington, eighteen miles distant. All the recruits, therefore, were employed to strengthen the defenses: and to their immense labor, the camp is indebted for its present almost perfect impregnability. The enlisted men were worked very hard and, to somebody’s disgrace, very poorly fed, receiving nothing but what could be taken with their bare hands, and not more than half rations at that.

National Archives and Records Administration Since Camp Nelson lacked enough officers to lead the USCT recruits, White soldiers left behind during the scramble to pursue Morgan’s force were ordered to help instruct the men. Most of the Black troops seem to have been organized into 100-man squads, with one White man commanding each. Strengthening the earthworks from sunup to sundown was backbreaking work, and the summer heat only added to the difficulties, especially since a drought was plaguing the area. Though the USCT recruits were primarily tasked with improving the fortifications at Camp Nelson, they were also ordered to perform guard duty along the earthworks during the height of the threat and be prepared to defend against an attack. Samuel J. Radcliffe, an assistant surgeon at the base, wrote, “Guns are grinning through the embrasures, while at intervals stands a big black fellow overlooking the parapet, silent and motionless, with a threatening scowl bidding defiance to all antagonists.”

National Archives and Records Administration June 13Giltner’s force, unbeknownst to the Federals in the area, did not want to attack Camp Nelson or any other sizable force due to their lack of weapons and consequently took farm paths and avoided roving patrols. After reaching Jessamine County in the early hours of June 13, Giltner learned from the locals that a force of US cavalry defended Nicholasville while Fry’s command defended Camp Nelson. With limited options, Giltner had to move his already depleted and worn-out command between the two enemy forces. Confederate captain Edward O. Guerrant, who was with the escaping column, later noted: Rode hard all night up and down hills and branches. O so sleepy! Many of the men lost their hats, guns and etc., and many were left asleep on their horses. Our 200 stretched two miles, most all asleep, horses and all. Rode hard all night and at daylight the next morning (June 13) crossed the Nicholasville and Danville pike. At (J) Butler’s (Tavern), just halfway from 350 Yankee Cavalry at Nicholasville and four or five hundred Negro soldiers and several hundred Yankee cavalry at ‘Camp Nelson or Hickman Bridge, just three miles from each. We quadruple quicked it here. Giltner’s rear guard was soon hit by a patrol, more than likely one of Fry’s scouting parties. Hearing the commotion behind them, Giltner’s force rushed toward the Sulpher Well community, roughly two miles from Camp Nelson. Unbeknownst to the scared Confederates, eight men, employees from Camp Nelson, defended the small community. In a skirmish that lasted very briefly, Giltner’s advance guard charged the outnumbered band and forced them to rush back toward the US Army base. Guerrant wrote, “We had not proceeded very far before a fire in front had the happy effect of enabling us to ‘close up.’ Our advance Guard ran upon the rear of the Camp Nelson pickets stationed at Sulpher Well. After some difficulty, our boys succeeded in charging them (8 in number), routing them, and running them off.” By now, dawn was approaching, and elements of Fry’s patrols were racing back into Camp Nelson. Not knowing the Confederates’ true intentions, the alarm was raised, and everyone, White employee and Black recruit, was rushed to help to man the forts and trenches and await a supposed attack. Surgeon Radcliffe related, “I was awakened about midnight by a darkey making a fire in the stove: in answer to an inquiry what is the matter he said ‘laws, missus, haven't ye heard the noise? All the men in the house, white and black, be ordered to the fort: Mars Will (meaning my son) be gone too, with a big gun, the rebels only three miles off.’”

Log College Press Once he realized that an attack was not coming, Fry dispatched a sizeable force of roughly 250 men in two detachments to follow the enemy’s movements and capture as many Confederates as possible – though it is important to note that the general did not turn to the USCT volunteers for this assignment, only the White employees. By the time the forces were collected and left Camp Nelson, Giltner’s men were already on the move. After routing the outer picket post at Sulpher Well, the Confederates continued south toward the mouth of Paint Lick Creek, which flowed into the Kentucky River. Along the way, Giltner decided to use a fear tactic that would hopefully discourage the Federals at Camp Nelson from pursuing them further. This involved telling the locals, mainly those close to Camp Nelson, that his men belonged to renowned Confederate raider Nathan B. Forrest’s command and that they intended to attack the base. Guerrent wrote, “The people generally appeared friendly to us, but were much surprised and frightened at our appearance among them and our surmised disaster, for we said very little, generally told (especially in neighborhood of Camp Nelson), that we belonged to Forrest, and were going to take Camp Nelson.”

National Archives and Records Administration AftermathThough the Confederate threat was gone, US cavalry spent the next several days capturing and hunting down the dozens of stragglers from Morgan’s cavalry in the local area and often took them to Camp Nelson. By June 15, life returned to normal at Camp Nelson, and traffic along the Lexington-Danville Turnpike through the base was resumed. The Confederates in Morgan’s raid never attacked Camp Nelson, but from June 9 to June 13, an impromptu force of White and Black men was vital in ensuring it was defended and its fortifications were strong enough to withstand an assault. |

Last updated: July 16, 2023