|

Few visitors to the Outer Banks realize that nearly 150 years ago these same islands were battlefields. The barrier islands of the North Carolina coast and the adjacent Pamlico and Albemarle sounds were the gateway to the rest of the state. Whoever could control these barrier islands and sounds could control North Carolina. Although not as famous as other great Civil War battles, the actions on the Outer Banks were pivotal for control of North Carolina, and even amid the hardships of the war, one island became a symbol of hope for enslaved people seeking a new life.

The Battle of Hatteras InletAugust 1861 In the 1860s Hatteras Inlet, between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, was the most traveled and most vulnerable inlet on the Outer Banks. After North Carolina joined the Confederacy in 1861, soldiers and enslaved people constructed Forts Clark and Hatteras, at the southern end of Hatteras Island in an effort to control access into Pamlico Sound. The taking of Hatteras Inlet was an early priority for Union forces. On August 28, 1861, seven Federal ships opened fire on Fort Clark. The great Union ships with their long guns remained far out to sea, well beyond the range of the Confederates’ feeble artillery. By midday the poorly equipped Confederate troops at Fort Clark abandoned their stations and fled to Fort Hatteras. A small contingent of Union soldiers landed and took Fort Clark. The taking of Hatteras Inlet was a morale boost for the Union and marked its first victory in the war. This victory was so important that news was dispatched to the White House, where President Abraham Lincoln, roused from bed in the middle of the night to receive the news, danced a jig in his nightshirt. With the breakthrough at Hatteras Inlet, nearly all of the Confederate-held East Coast between Wilmington, N.C., and Norfolk, Va., would begin to crumble. Pamlico Sound and its major cities of New Bern and Washington, N.C., were the first step, but the Union had its sights on bigger prey.

The Chicamacomico RacesOctober 1861 Roanoke Island remained a Confederate outpost and was the only thing standing in the way of Union control of the Albemarle Sound, which along with Pamlico Sound, would mean total Union dominance of eastern North Carolina. Confederate troops began massing on the island, and if their numbers swelled sufficiently, they could cross the sound to recapture Hatteras Island and regain Pamlico Sound. In October 1861, Union forces established an outpost 40 miles north of Hatteras Inlet at Chicamacomico, today known as Rodanthe. When the Confederates discovered the Union presence in the village, they launched an attack on the troops there. When the Federal commander saw Confederate ships crossing Pamlico Sound, he ordered his men to flee south to Fort Hatteras.

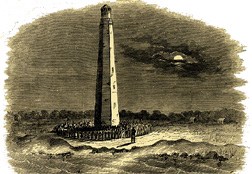

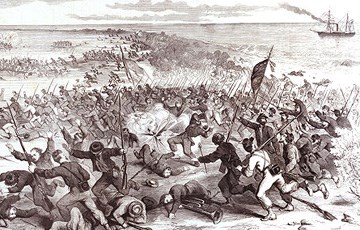

Abandoning their planned attack, the Confederates began the march back to Chicamacomico the next day. Additional Federal troops traveling north from Fort Hatteras passed the lighthouse and caught up with the Confederates. Now it was the Confederates’ turn to run, all the way back to Chicamacomico. The Battle of Roanoke IslandFebruary 1862 Union forces again set sights on Roanoke Island, the linchpin in North Carolina’s coast. It was vital for Confederates to hold the island. If the Confederates lost Roanoke Island, it would only be a matter of time before Albemarle Sound, its port cities, and back-door access to Norfolk would also be lost to the Union. Losing Roanoke Island would mean losing all of eastern North Carolina. The Confederate commander on Roanoke Island had no military training, but he recognized his vulnerable situation, pleading for reinforcements, but never receiving them. Only one road ran north to south along the length of the island. Confederate troops built fortified earthworks on the road at the center of the island to defend against a land-based assault. Confederates also constructed forts on the northwest coast of the island, enabling cover of a water-based assault from the west. Union ships with their longer guns, came from the south, but remained easily out of range of all but the southernmost fort, which they quickly disabled.

Late in the afternoon of February 7, 1862, Union troops landed with the aim of assaulting the earthworks and road at the center of the island. The soldiers quickly captured the landing site and spent a wet night before the battle. At dawn the Union troops successfully pushed through thick marshes to fire on the flanks of the earthworks while others attacked from the front. The Confederate troops were overwhelmed, fleeing to the north end of the island, where they ultimately surrendered Roanoke Island to the Union. The fall of Roanoke Island opened eastern North Carolina to Union control. By the summer of 1862, the port cities of Plymouth, Elizabeth City, New Bern, Washington, Edenton, Hertford, N.C., and Norfolk, Va., had all fallen to Union forces. The vital rail line carrying supplies from Wilmington—North Carolina’s only remaining Confederate port—was also vulnerable. With the huge success at Roanoke Island, the Union stranglehold on the South was ever tightening.

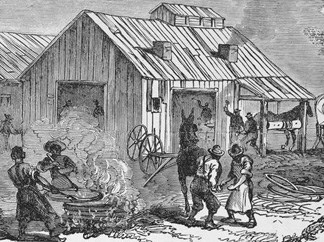

A New Life"If you can cross the creek to Roanoke Island, you will find safe haven." Following the fall of Roanoke Island, the Union Army was faced with the question of what to do with the enslaved people who had been sent to help build fortifications on Roanoke Island. Labeling the enslaved people as “Contraband of War,” the Union Army emancipated them, offering a new start on the island. Word of a “safe haven” spread, and soon hundreds of enslaved people from the interior of the state made the journey to Roanoke Island. Men rebuilt forts and served as woodcutters, teamsters, longshoremen, carpenters, and blacksmiths. Women were employed to cook and clean for Union officers. Other African Americans were employed as spies, scouts, and guides and completed many invaluable missions for the Union.

By 1863 the population of freed enslaved people on Roanoke Island was so high that the Federal government established a formal Freedmen’s Colony on the island with the mission to “settle the colored people on the unoccupied lands and give them agricultural implements and mechanical tools…and to train and educate them for a free and independent community.” Lands were cleared and roads built. A sawmill operation, as well as schools and a church were all constructed in the colony. By 1865 the Freedmen’s Colony population had reached nearly 3,500 people. While the Freedmen’s Colony only lasted until the end of the Civil War, colony residents enjoyed homes, jobs, and education for the first time, and found a renewed sense of hope in their new community. Descendents of the freedmen still live on Roanoke Island today.

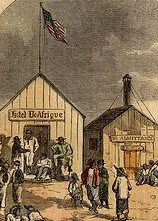

Hotel d'Afrique1861 Juneteenth is the commemoration of the official end of slavery for enslaved people still held in bondage deep in Confederate territory. For the estimated 500+ enslaved people living on the Outer Banks and countless others in eastern North Carolina in 1861, their bondage ended with the cannons fired by fellow Black citizens. Moving OnWithin two years, although the war was raging in places like Vicksburg and Gettysburg, the Outer Banks became a quiet duty station for the Union troops. The clashes of war had moved elsewhere. Just like the waves of the ocean, the waves of war had washed over the Outer Banks. In 1864 the Union decomissioned Fort Clark and moved the remaining soldiers to Fort Hatteras. By 1867 even they were gone. Following the end of the war in 1865, the government ordered all the Freedmen’s Colony lands on Roanoke Island returned to their original owners. Most freedmen left the island, since they had failed to receive rights and privileges to their homesteads. The island’s population of freedmen quickly dropped to only a few families remaining in 1866. The colony was officially decommissioned in 1867. The colony never became the self-sufficient, permanent community that its planners had envisioned. Though the colony is gone, it remains an enduring symbol for descendents of the freedmen, and descendents of all African Americans who sought their freedom during the Civil War. Today little physical evidence remains of the forts and battle sites, or even of the Freedmen’s Colony. Change is a constant on these shores, just as it is in the annals of history. Natural processes have overcome these features from a short period of history on the Outer Banks. Instead of bullets and bombardment, the only sounds heard today are the blowing wind, the calling of gulls and the pounding of surf, as nature has reclaimed the works of war. |

Last updated: July 27, 2021